Looking back at his Motor Cycle years during the mid-1970s, Pete Kelly recalls the drawn-out saga of Norton Villiers Triumph and the Meriden workers’ co-operative along with a few more memorable tales.

For the revamped Motor Cycle, March 1975 brought an office move from London’s Fleet Street to new premises in Sutton, Surrey, causing tremendous disruption to the commuting routine of its staff. But for former Motor Cycle News editor Charlie Rous, who’d joined the team the previous year and had been happily taking the daily train journey from his home near Market Harborough into central London and back, it was a step too far, and sadly he decided to leave.

The hectic press night routine, which meant collecting and processing of incoming films of sporting events all over the country from London’s main line stations, still demanded a Sunday evening office location in the capital, and we ended up sharing one with Cycling magazine. After that – at around midnight if we were lucky – someone (usually me!) had to drive to Colchester, Essex, to hand over the contents of the front cover and sports pages to the night shift at QB Printers before snatching a few hours’ sleep in a nearby hotel and then spending the whole of Monday carefully checking and signing off the final page proofs. Not the best recipe for a contented family life!

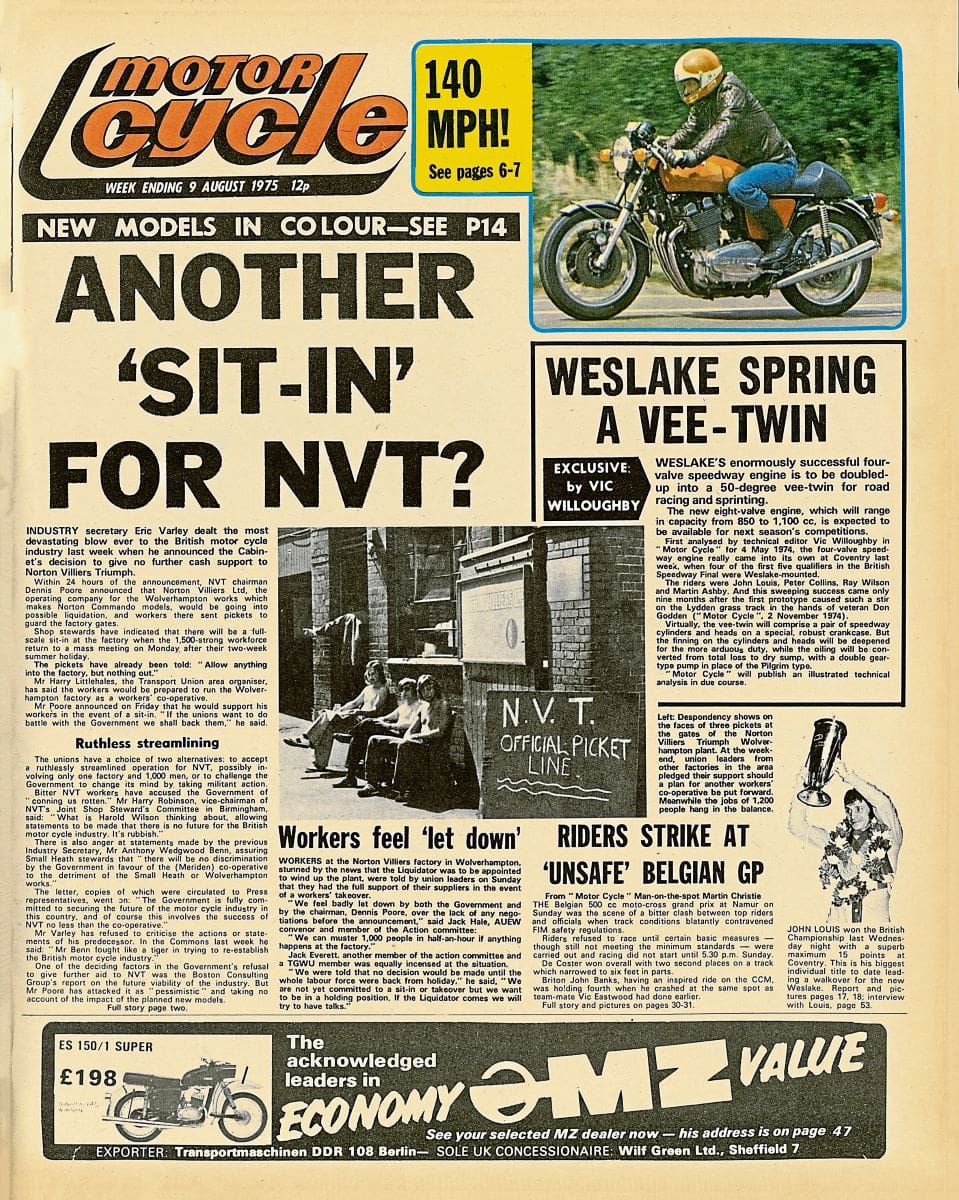

The year 1975 also proved seismic for the scant remains of the British motorcycle industry. Rarely did an issue go by without the latest news about the continuing saga of Norton Villiers Triumph and the Meriden workers’ co-operative, with the mood constantly ranging from glimmers of hope to utter despair.

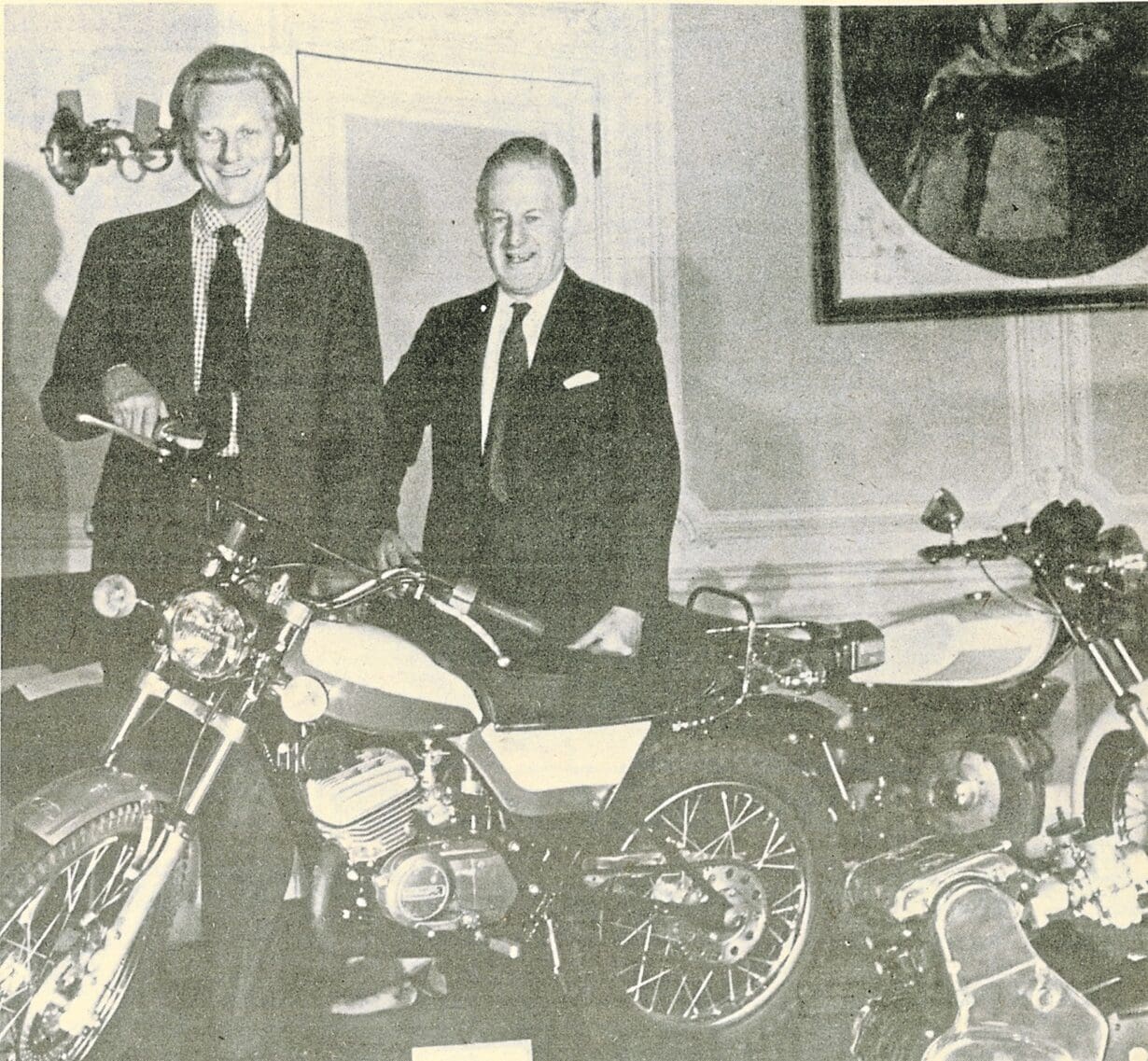

The issue dated July 19, 1975 announced the forthcoming unveiling of NVT’s much-heralded water-cooled, twin-cylinder Cosworth engine, which would be on display at a London press gathering, along with Norton’s twin-rotor Wankel engine and prototypes of possible lightweight models for British and world markets. This might have seemed encouraging if it hadn’t been for the page three heading in the same issue, ‘Cash now or we start to close – Poore’ (NVT’s chairman Dennis Poore).

A week later the cover headline was ‘Three cheers for Britain’, with a picture of the Cosworth twin that was named the ‘Challenge’. A page three heading suggested ‘This great industry must be saved’, while in ‘Race Gossip’, sports editor Mick Woollett asked: “Can the Cosworth beat the Japs?”

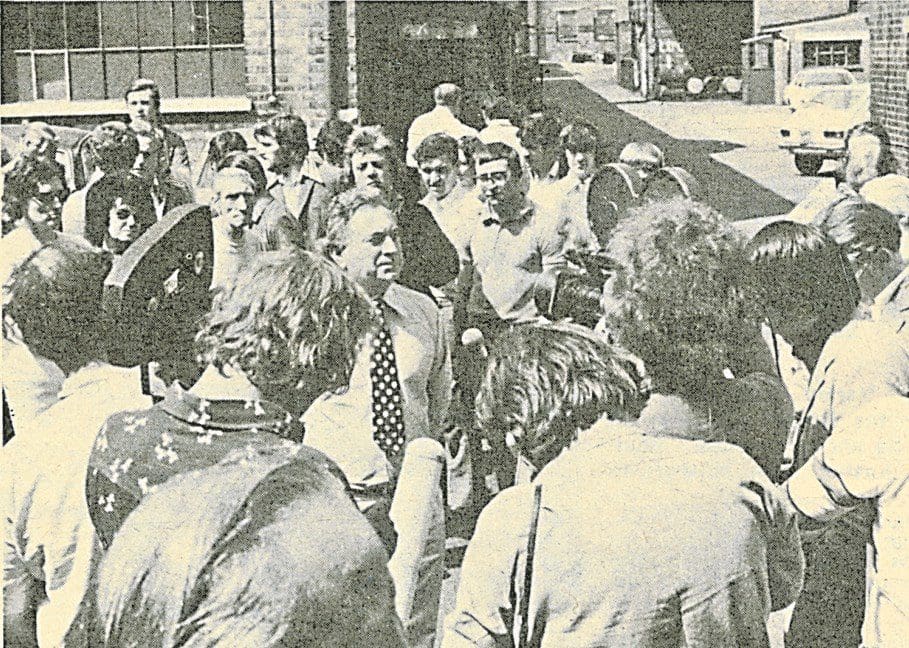

It took only a fortnight for the mood to darken again when, following a government decision to inject no more money into the firm, the August 9, 1975 cover heading announced ‘Industry Secretary Eric Varley deals devastating blow’. The inside pages contained a feature headed ‘An epitaph to what might have been at NVT’, and in a page three news item, Poore said: “In our judgment the government has done more to damage the British motorcycle industry than all the might of the Japanese. This extraordinary decision shows a callous disregard for the effect on the livelihoods of thousands of men and for solemn assurances given by the previous secretary of state, Mr Benn.”

Some pruning at NVT was now inevitable, and from the viability point of view the Norton Villiers Ltd plant at Wolverhampton would have to go first. Ironically, in the days before the BSA-Triumph collapse and the subsequent formation of NVT, it had been a profitable concern, and there hadn’t been a serious dispute at the factory for 50 years.

Just under a month later, the Wolverhampton workers were urging dockers to ‘black’ the import of Japanese motorcycles, even though by then many more people in Britain depended on Japanese and other foreign-built machines than British ones for their livelihoods. What a cruel saga – especially as motorcycle sales figures for the first 10 days in August had increased by a staggering 81%! Advertisements were coming in like an unstoppable flood and Motor Cycle easily managed to produce a 26-page preview for the 1975 Earls Court Motorcycle Show that would be taking place from August 30 until September 4.

Almost predictably, the cover headline in the following issue was ‘Boom… and Gloom!’, with NVT director Hugh Palin denying a previous suggestion that production of the Triumph Trident was about to end, and Midland Editor Bob Currie writing a feature entitled ‘Behind the Wolverhampton picket line’.

There would be plenty more to come in this unhappy chain of events, and with sharply divided opinions between pro-British and pro-Japanese supporters, our readers wasted no time in letting us know where their passions lay.

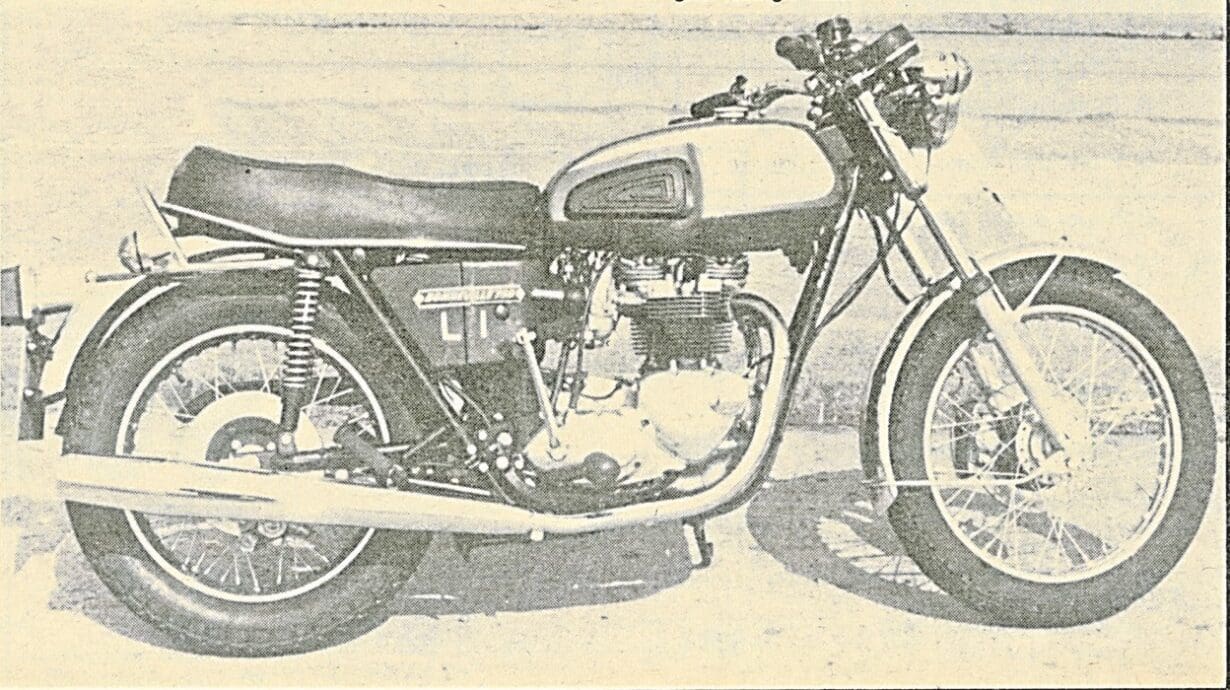

We always gave equal attention to the budding Meriden workers’ co-operative, and after its first two prototypes had been submitted to NVT (which was contracted to market 48,000 of the Triumph twins up to July 1977) for evaluation, the machines were criticised as being “unsatisfactory from a marketing point of view, not compliant with recognised safety standards, too noisy and vibrating too much.”

Sour grapes can taste very bitter indeed, and were the cue for John Nutting to pay a visit to Meriden and talk to the co-operative’s chairman Denis Johnson before trying out one of the bikes.

“If NVT get them there, dealers in America say that the machines would be in and out of the showrooms so quickly they’d hardly touch the floor,” he said in his spartan office, adding that the details of the report had been quoted out of context before he had even seen it, and that most of the points made referred to details like the lack of a trademarked silencer, a certification plate on the steering head, no mirrors and the wrong type of front brake hosing – all of which had already been sorted.

Two of the biggest headaches for the co-operative had been the adoption of a hydraulically operated rear disc brake and cutting the noise levels to the strict standards in California, Meriden’s biggest and most important market.

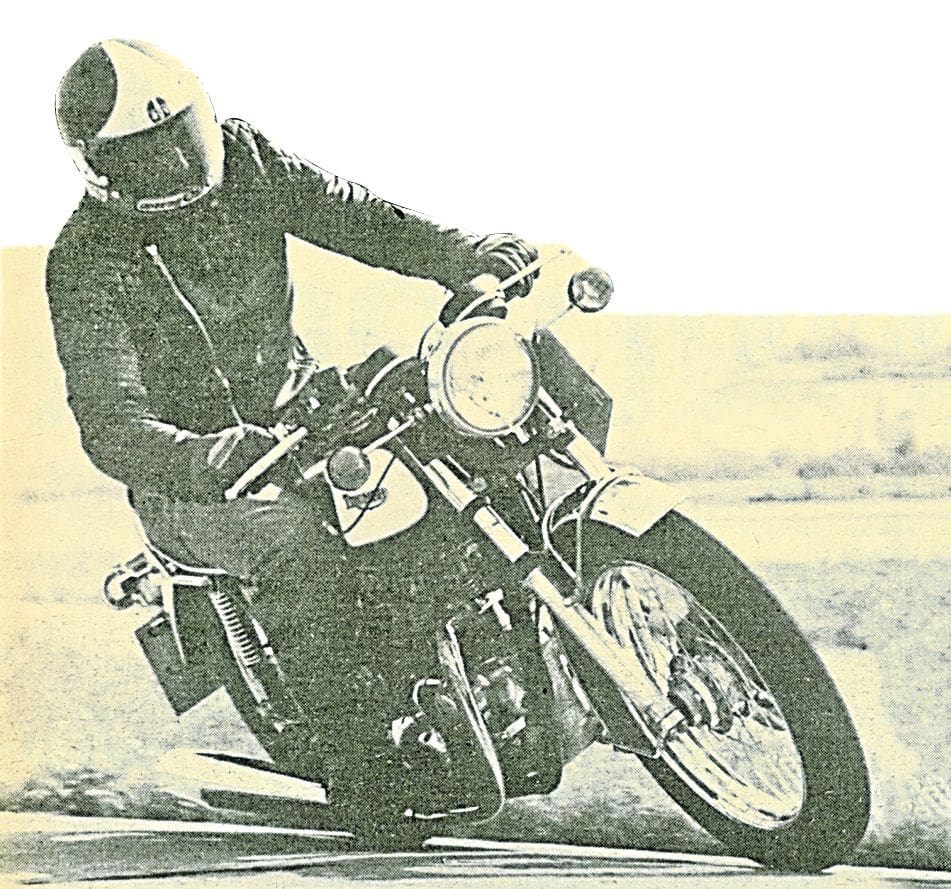

John was quick to mention that the bikes were substantially to the same specification as the last machine he’d collected from Triumph for a road test in 1973 – a single-carb TR7RV Tiger that had been one of the first to be made – so it came as no surprise when he took a spin around the Warwickshire lanes on the latest 1976-model Bonneville that it felt much the same.

“At around 420lb, the Triumph twin is the lightest seven-fifty in production, and as a result is tremendously responsive,” he wrote. “Being so light, it can be flicked from side to side with an abandon that would end up in the ditch with most other superbikes.

“As expected, the Bonnie vibrated just as they have always vibrated, and anyone who expects otherwise is kidding himself. This is the price you pay for having a large capacity, cheaply made parallel twin with none of the weight-adding complexities of other superbikes.”

John suggested a few improvements, such as better forks (as they leaked) and a more comfortable riding position, but he agreed that the priority was to get the machines out of the factory and into the dealers’ showrooms.

Morale among the 430 workers was high as production got into its stride, but with the question mark hanging over NVT, how would future machines be sold? Denis Johnson said: “We would very much like to market the bikes ourselves, and have had plenty of offers from other organisations to do so.”

Impressed by such confidence, John wondered whether Meriden would have the last laugh over NVT after all.

The Motor Cycling tradition of sports news lived on, especially in view of the ongoing battle with rival publication Motor Cycle News, and, during 1975, the publication entered a team of three Honda CB400Fs which we nicknamed Faith, Hope and Charity into that year’s production TT as well as sponsoring a major sidecar championship.

Before joining Motor Cycle, I’d been working in Darlington and had a turquoise 850 Mini as family transport. Back then, competitors in sidecar racing were commonly referred to as ‘charioteers’ so I had the brainwave (?) of fitting the Mini with a twin-carb 1100cc engine, having it painted orange with large Motor Cycle logos against each white-painted door, fitting a tow bar and then getting Warrington sprinter Pete Williams to fabricate a trailer chassis built up with aluminium sides in the shape of a Roman chariot with the idea of parading the winners around the circuits in it.

Pete, who had started sprinting in 1964 at the age of 23 and later became a secretary of the National Sprint Association, will be remembered for his double-engined Triumph ‘Two-Faced’ on which he became one of the three quickest sprinters in Europe. But sidecar racers of all people certainly knew the meaning of danger, and their reaction to the chariot was: “We’re not getting into that thing!” so it ended up hauling the CB400Fs about during their extended careers in mainland production racing!

Motor Cycle also placed a big emphasis on road tests of new motorcycles. Among those tested by John Nutting in 1975 alone were the BMW R90S flat-twin, Yamaha XS500B dohc twin, 850cc V-twin Moto Guzzi T3, 1000cc Laverda Jota triple (which reached almost 140mph in his hands at the MIRA testing ground and got me a speeding ticket on the M6), Suzuki GT750M two-stroke triple, Harley-Davidson Sportster V-twin, 850cc Norton Commando Mk III twin, Kawasaki Z1 1000cc four and GL 1000 Honda Gold Wing.

The rest of us, including Bob Currie, Jerry Clayton, Martin Christie, Dave Calderwood, Stewart Boroughs, David Wilcock and Dave Richmond, also got our hands on a plethora of machines.

By 1975 many excellent trail bikes, influenced by American tastes, were coming on to the market. Before long, British ramblers started complaining about trail riders shattering the peace of the countryside, which led to an experimental closure of a two-mile section of the Great Ridge Way following an ancient chalk ridge.

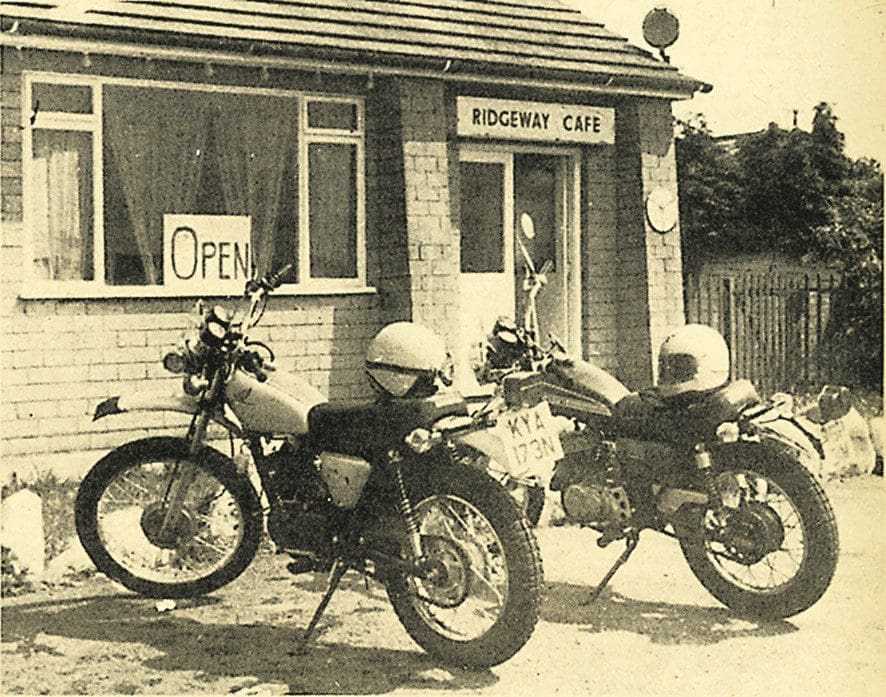

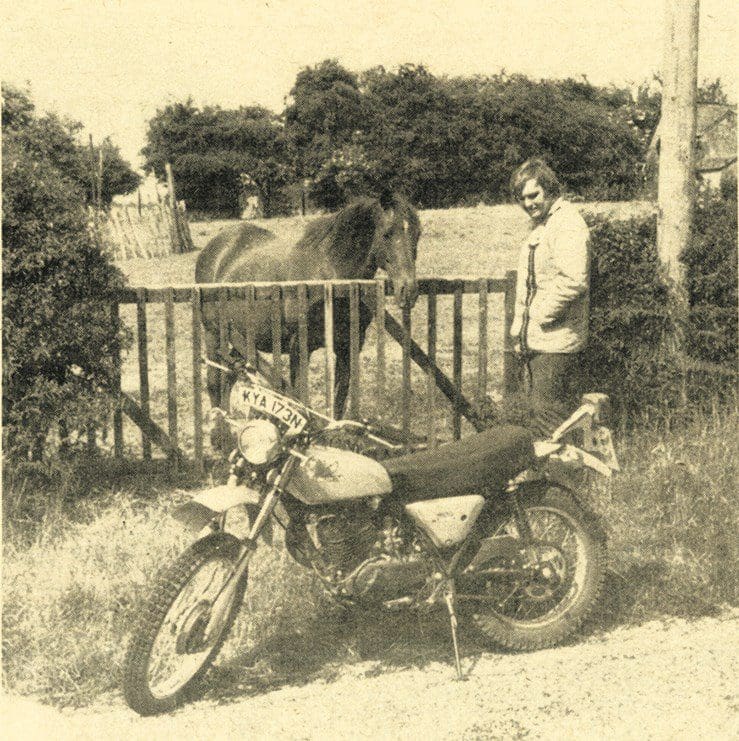

Motorcyclists’ rights champion Bruce Preston, who’d already fought against proposed legislation ranging from compulsory passenger insurance to the 70mph speed limit and the raising of the minimum licence age to 17, decided to make a stand before the closure came into effect by riding over 40 miles of the ancient road, and invited me to accompany him. He’d got his hands on what was believed to be the only MT250 Honda Elsinore trail bike in Britain at the time, and on the glorious summer’s day of July 12, 1975, I met up with him at the well-known Ridgeway Cafe at West Overton on a 250cc Suzuki trail bike. A cracking breakfast of sausage, egg, beans, bacon and fried bread, served with toast, marmalade and a cup of tea (all for just 64p!) made the perfect start to the day.

After setting off on the stretch between Blowingstone and Hill Barn, our attention was suddenly diverted from the rutted surface by what seemed like an invasion by St Trinian’s! The girls, all in school uniform, were walking along taking copious nature notes, and I made their day by stalling the Suzuki right in front of teacher!

The Way is scattered with ancient remains and other interesting sidelines on the country’s history. Butterflies danced delicately by, and grey squirrels bounded away in front of us where the Way narrowed beneath a tunnel of trees. Our confidence quickly grew and soon we were making a comfortable25-30mph.

In places the Way widened and had a smooth chalk surface, with downhill stretches making braking quite hazardous. After saving a long sideways slide more by luck than judgment, I saw Bruce going straight over the top after the front wheel of his Elsinore dug in, thankfully with no harm to bike or rider.

Before venturing on to the short section of the Ridge Way that was about to be closed, we called at The Plough, in the thatched village of Kingston Lisle, for a cooling pint and an excellent toasted cheese sandwich – and the licensee had no idea of the impending closure order right on his doorstep.

The mostly wide and well-rutted ‘doomed’ section between the village and Lambourne proved disappointing, the obvious use by cars no doubt being one of the reasons behind the closure. We found battery-operated counters in four places along this section, although we weren’t quite sure what they were meant to achieve, and for whom.

From the ancient burial mound at the end of this section to the tall family monument overlooking Wantage, much of the Way was wide, and being grassed over in many places made our riding easier. We met a party of weary hikers from Southport who’d been at our starting place three days earlier. They didn’t mind bikes in the least, and one of them remarked that two wheels was a much better way to make the trip than on two feet!

At Gore Hill, the Ridge Way became a footpath only, so we took another track to Compton village to rejoin it at Roden Downs and thence to Streatley, where it became a normal road and was not marked again on the map.

Our adventure ended in Henley-on-Thames just before 5pm. For me, the ride had brought an exhilarating day out of the office, and I’d learned lots about trail riding, not to mention the Great Ridge Way itself. I concluded that the ‘fight’ for this ancient trail was not purely about the rights of any one group or another, but for the rights of everyone to enjoy the great outdoors – with consideration for others from all sides, of course.

The most travelled member of Motor Cycle’s staff was sports editor Mick Woollett, who covered all the road racing world championship grands prix along with other major events such as the Daytona 200 and, a few weeks after the Ridge Way ride, I accompanied him to the Dutch TT at Assen.

In the July 19 issue I described the amazing atmosphere at this annual classic, which wasn’t just an important road race but also a fantastic, colourful carnival that went on into the early hours of race day in the otherwise quiet town of Assen. Every shop, whether it be a grocer, chemist or ironmonger, had a motorcycle display in the window, and it was uncanny to see a vintage bike, a scrambler or a road racer nestling among colour TV sets, shoes or women’s fashions, but that’s the way it was. Everyone made an effort, right down to the electricians with their own flashing TT displays.

As dusk fell on the night before the race, the whole town came alive. Hot sausage stands, motorised ice cream trikes and coffee stands appeared from nowhere, and pavements and streets were suddenly choked with them. Huge beer marquees had been erected here and there, crowded to their door flaps by motorcyclists from all over the continent, determined to make the most of the fantastic evening.

Just opposite, the steady voice of a Salvation Army songstress was amplified all around as she preached her own message, with a large, respectful crowd of motorcycling onlookers gathered around. Then another sound came from a side street where an electric organ shop was lit up as a man and a girl gave a melodious rendering of popular tunes from the shop window. With a tinkling of bells, a group of young people came tearing past on those fantastic tall Dutch bicycles, their pillion passengers sitting side-saddle on the hefty rear-mounted carriers.

In streets not closed to motor traffic, motorcyclists got away with murder, revving their open-pipe machines until they seemed ready to burst, and loud applause came from all around as more beer was downed! At the top of a main street, a huge outdoor movie screen glowed as the projectionist in the back of a van across the road sorted out his motorcycling from his pop music films.

The crack of fireworks could be heard all over the town, and within easy walking distance from the town centre, the approaches to a fairground were lined with stands selling everything for the Dutch TT gourmet, from smoked eels, lashed in threes like whips, to candy floss and hot sausages. The fair made some of our own village green efforts look mild. Some rides, like the Assen Express, a fast-moving train that took banked corners and looped at a tremendous speed, were frightening, and then there was the Skylab, a kind of flying saucer that was jacked up on to its beam ends and ended up with the occupants looping the loop at high speed in their wire-covered, suspended cars.

A muscular African gentleman stood on a boxing booth, a huge grin spread across his face, while the ringmaster tried to persuade motorcyclists in the huge crowd before them to have a go at challenging him. Nobody was committing himself, but the night was still young…

Back in the town, a balancing act was in progress in one of the squares as a rider gingerly took his 160cc Honda twin, its tyres removed, along a rope to a tall mast in the middle of the square. Below him swung his counter-balancing accomplice on a suspended cradle. Youngsters on chopped 50cc Kreidlers buzzed about as more and more riders came into town, their Honda fours, Kawasakis and BMWs laden with camping gear. They’d been on the road since leaving work and it was now 11pm, but in one of the squares a man was still polishing away on an old banger demonstrating the miraculous properties of his car wax. He’d been there since 10am!

From first light on race day, fans started crowding the banking around the five-mile circuit and using polythene sheets as windbreaks as they cooked breakfast on primus stoves. From early morning onwards light aircraft could be seen trailing banners advertising everything from Sony TVs to King Willem cigars, joined one by one by others until no fewer than 22 planes filled the sky, and they continued forming and re-forming for the rest of the day.

And the racing hadn’t even started at that time!

Ten years before I joined Motor Cycle, I used to join my motorcycling mates at a pub in a village outside Warrington called The Noggin, and when news reached my desk that a new landlord had told the 40 or so bikers who still met there that they could no longer park their machines in the car park or take their riding gear into the pub, I decided to chase it up as a news story.

In the issue dated September 6, 1975, we were able to bring the good news that the ‘Battle of the Noggin’ had been won when the regional manager of local brewery Greenall Whitley, which owned the pub, met the new landlord Mr Miles Vaughan and all of the issues were quickly resolved, with a special parking place for the ‘Noggin Gang’ and hooks for coats and helmets. There were also plans to open a new bar for the motorcyclists, several of whom, including my brother Geoff, also attended the meeting. World leaders, are you listening?

The Noggin’s previous landlord, Councillor Walter Farringdon, had gone out of his way to give his two-wheeled customers somewhere pleasant to meet, and, on the few occasions when things got a little noisy, he could be as firm as the next man. On occasions, a special bar was set up round the back in the early days so that ‘Nogginers’ could have dances and parties.

A lot of the lads used to race at local circuits such as Oulton Park, Aintree, Wallasey Promenade and even Prees Heath and some, like Brian Ball and Vin Duckett, went on to greater things. At the time I was riding a 250cc Cotton Telstar in local club races, sometimes even making it into the finals, but once, when I asked why it had suffered a seizure, the consensus of opinion was that I was a bloody awful mechanic and not much better at riding!

The Noggin Gang, whose helmets were painted yellow with a black ace of clubs on the front, was full of characters like Peter Poole, a gentle giant of a bloke whose favourite trick was to wait until another regular, Sammy Green, started up his Honda Monkey bike and then lift the back end, complete with Sammy, clear from the ground with one hand and stand there grinning as he watched the back wheel flailing around in mid-air.

Ken Rowland, generally accepted as the Noggin’s ‘Godfather’, used to race a Goldie, and to hear him talk you’d think the works Hondas would never have stood a chance! Then there was Colin Wilkinson, better known as ‘Twink,’ who’d be riding in that year’s ‘Manx’.

He once opened a motorcycle shop at Sankey Bridges, where one perk for his customers (usually scroungers like myself who had no intention of spending anything other than the time of day – although I did hand-paint the shop sign!) was home-made hot dogs, the sausages ‘fried’ in what tasted like engine oil in a makeshift ‘frying pan’ made from a split-open Rock Oil container.

My conclusion was: “Let’s raise a toast to the good times, and if any readers have stories about their own favourite joints, tell us about them.”