Ariel enthusiast Dave Owen owns one of a small run of alloy-engined KHA twins built to celebrate the marque’s fine achievements in the ISDT.

Words: STEVE WILSON Photographs: GARY CHAPMAN

Dave Owen’s Ariels have featured in TCM already. His VB 600 SV single was tested in March 2019, and on a Dutch Ariel rally, his VH ohv 500cc Red Hunter single, exceptionally well-kitted, helped out my ailing NH 350cc with infusions of oil from its neatly-mounted spare container, with a matching bottle of emergency petrol.

A stalwart of the Ariel Owners’ Club, Dave’s definitely the right man to own this special-built version of Selly Oak’s 500cc twin, featuring an all-alloy KHA engine, only produced for the 1953 model year.

With flying colours

With 1953 also being the coronation year, Ariel had celebrated with the distinctive white-lined Wedgwood Blue as the standard finish for the alloy-engined 500cc twins and the new 4G Mk.II Square 4, though Dave confirms that the colour did remain an option on both models for the following four years. “You see a lot of different variants of the colour,” he observed ruefully.

In this case, the pale-ish blue colour undoubtedly lightens the appearance of what is already a machine lightened in reality. The alloy engine shed some 15lb compared with the standard all-iron one (the KHA was catalogued at 370lb dry v the KH’s 384lb), and this special is much lighter still.

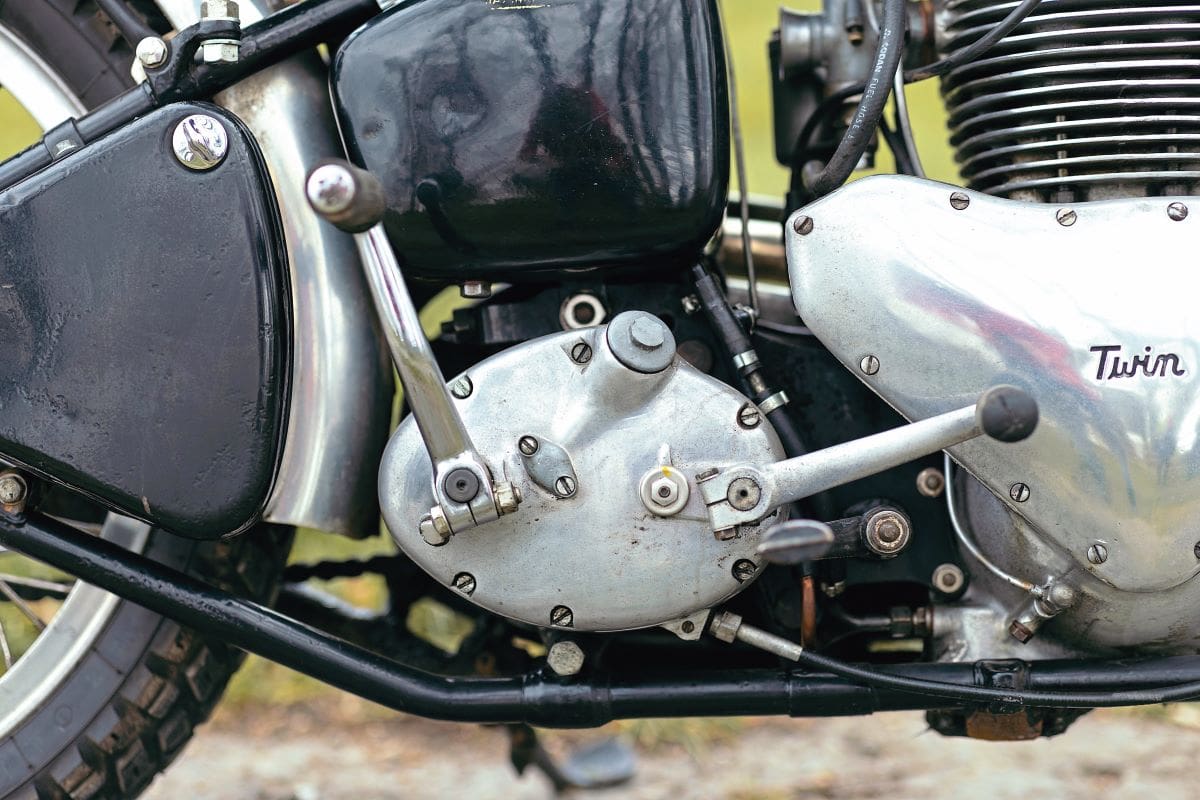

The 1953 KHA featured as standard the Anstey-link rear suspension chassis, but this special has a lighter, previous rigid frame; plus a single silencer on its (probably custom-made) exhaust system; and alloy wheel rims, shod with modern German Heidenau enduro-type tyres with motocross inner tubes, for its 3.50 x 19 rear and 3.0 x 21 inch front covers (the original front wheel had been 20 inch, for which Dave says tyres, previously a problem, are now available from Avon). The result is a dry weight which Dave puts around the 330lb mark. With the optional 7.5:1 pistons giving up to 28bhp@6200rpm, that’s a pretty good power-to-weight ratio for an early 1950s-based machine.

White-lined Wedgwood Blue finish, standard colour

for new 1953 KHA and 4G Mk II Square Four, celebrated

the Queen’s coronation year.

Designer Val Page’s 500cc twin, with ISDT-developed alloy

head and barrel, in production for 1953 only.

Dave gave me the origin story. “The bike was built in the mid-1990s, one of three put together by long-term club enthusiast, the late Bruce Sims. It went to an owner in Nottinghamshire who rarely used it, over the years putting on just 4000 miles. A friend acquired it and rode it more, and I asked him for first refusal. I got it in March 2021, and in the intervening year I’ve covered around 2000 trouble-free and enjoyable miles. The oil pressure is good, and an anti-wet sump valve has been fitted. I’ve never had it apart, just changed the front brake cable.

heat-dissipating black paint for seven-inch front brake, and

polished alloy guard.

version from 1955.

“It’s a bitsa – the frame is from 1949, the alloy barrel 1953, while the crankcases and head are from 1956. The gearbox is from 1955, a Burman GB34; internally, it had featured trials ratios giving very low gearing from first to third, so I changed the clutch sprocket from 44T to 40T, for a more relaxed ride on the road.”

And the object of Bruce Sims’ original exercise? To build, not replicas of, but tributes to, Ariel’s 1952-53 KHA ISDT machines.

A new twin

Designer Val Page had actually had a 500cc twin in preparation for Ariel in 1939. War then stopped play, but his KH Red Hunter and its KG De Luxe (but actually cooking) stablemate, were offered for 1948, a full year ahead of their AMC and Royal Enfield 500cc twin equivalents. Only Turner’s great original Speed Twin/T100, and BSA’s 1947 response, the Herbert Perkins’ A7, had preceded it. Page’s twin used many of the cycle parts from the existing singles. One exception was the front frame, which was built further forward at its lower end to clear the twins’ front-mounted dynamo, with duplex tubes under the engine to give a full cradle.

Page’s 500 did resemble Turner’s Triumph twins, with its twin cam layout and 499cc (63x80mm) capacity. But in several significant areas, Page had improved upon the original. The camshafts ran the full width of the engine, and were less prone to wear than the Triumph’s. A gear oil pump was selected rather than the Triumph (and the Ariel singles’) plunger pump, a weak point on the Meriden offering.

saved weight – one less silencer.

The Ariel’s crankshaft, unlike Triumph’s built-up item, was a one-piece forging, originally in steel. The camshafts were chain-driven, unlike the rattling, whirring gear drive on the Triumph. Handling was good, aided by a low centre of gravity, both on the standard rigid and optional Anstey-link versions. Although the latter, undamped, bounced about on bumpy bends, its plunger system’s unique design feature, which kept the rear chain in constant tension, according to one owner, really worked, delivering rear chain life of 25,000 miles, some three times the norm. The well-finished twins, like all four-stroke Ariels, provided a very comfortable ride.

Billed as ‘Son of the Gent’ (i.e. of the exclusive Square Four) the KH was reassuringly expensive (£235 against the T100’s £223). Unfortunately, this didn’t help sales, which remained moderate. Neither did Ariel’s rather staid image by then, nor Selly Oak’s antiquated premises, where post-Second World War annual production rarely exceeded 10,000. But though other 500s – and soon the new 650s – sold better, I have never met or read about a KH owner who wasn’t happy with his Ariel twin.

Tester Steve Wilson enjoyed the lightened Ariel twin’s acceleration.

Going for gold

But one way that Ariel, along with other companies, chose to promote sales of their twins at home and abroad, was by selecting them as mounts for the prestigious International Six Day Trial – despite the fact that as off-road photographer, writer and authority Don Morley observed, riding twins competitively in the dirt was a skill given to few.

Britain previously had dominated this annual competition, usually held in September, by 1950 having won the top Trophy award in 16 out of the previous 27 events. Other awards went to three-man Silver Vase A or B teams, and to successful Manufacturers’ Teams.

Individuals in all teams, and club or solo private entries, who lost no points at time checks over the six days and 1200-plus miles, were awarded a Gold Medal – and the medals were of real, solid gold in the immediate postwar period. On a mixture of tarmac and off-road, the national Trophy teams had to compete on machines made in their own country, in at least two different engine sizes.

The first postwar ISDT was in Czechoslovakia in 1947, with Britain not officially entering due to short notice on the regulations. Already the lighter, nimbler smaller capacity two-strokes, like the winning Czech team on Jawas, and the Austrian Puch 125s, were rising to threaten British supremacy. A final speed test on the sixth day, postwar run on closed tarmac roads, should have favoured the larger capacity Brits, but the advantage was progressively handicapped out; by 1953 the British Trophy team had to average 62mph lapping a three-mile circuit, while for the Czech 250s it was 44.7mph. There were two ways to redress the balance: making the big four-strokes lighter; and outriding the opposition.

Ariel’s top rider was the likeable CM ‘Bob’ Ray. He had started early, rounding up cattle on the family farm in Devon aboard an Ariel field bike. In the Second World War, his skill led to selection as an Army DR instructor in Kendal, and successes in Service competitions saw him signed up with Ariel postwar as a works rider in trials, scrambles and the ISDT. He survived the extremely hairy 1948 event in San Remo, Italy, where on a donkey track he’d had to throw his Ariel down in the dust to prevent going over the unprotected edge of a cliff. He was part of the winning British Vase A team, with Britain also taking the Trophy; Triumph, part of that team, from then on dubbed their dual-purpose twins ‘Trophy’.

In the 1949 event in Wales, Bob Ray was now part of the British Trophy team, which included AJS’s Hugh Viney and Triumph’s Jim Alves. The team comprised, thanks to the British selectors, one machine from each of the major manufacturers – sporting, but not the most practical arrangement re preparation, spares etc. At one point Ray lost his way, and hurrying to make up time, with only one (fading) brake operational, hit a car, dropped his record card, and returning to retrieve it, was late clocking in and lost one (potentially vital) mark. But the Brits took the Trophy, with the Czechs winning the Vase.

Last ditch effort

As Walker and Carrick put it in their excellent book on the ISDT, the event had been “essentially a reliability trial for production motorcycles in everyday use.” Emphasising this, a night run was introduced for 1950’s event, again in Wales, to ensure functional lighting systems – with Italian electrics reportedly not showing well! But by the mid-1950s some of the Middle European team entries were far from standard, or available for purchase.

Meanwhile however, the Brits did what they could, in the light of experience fitting extras like air bottles, nail-catchers, qd fitments etc. But more particularly they lightened their roadsters. Ariel works twins for that year had alloy petrol tanks and wheel hubs, Burman gearbox shells cast in Elektron, and siamesed exhaust systems. They also attempted to counter the undamped Anstey-links’ pitching on bumpy bends, by a concealed hydraulic system which allowed the use of softer springs; but this was unsuccessful due to an inadequate fluid reservoir. However, despite appalling weather conditions, with competitors reduced from an initial 213 to an eventual 83, Britain won the Trophy and the Vase, convincingly. Ariel, as well as AJS and Triumph, took Manufacturer’s Awards.

The Italians hosted the 1951 event in Varese and the hot and dusty hills behind it. The Brits knew this would be a fast one and opted for all twins, 500 and 650s, despite more severe handicapping. Organisation was sometimes chaotic, and schedules dictated that some mountain tracks had to be covered at speeds verging on insane. This was for real: of three BSA works riders, the first was badly concussed on the night run, the second thrown over the bars and down a cliff, and the third suffered a fractured jaw, teeth knocked out, and a spinal injury. Despite all, the Brits, with Ray on the team, narrowly won the Trophy, with the Dutch collecting the Vase – on Czech-built Jawas.

Alloy, alloy!

Ariel had again won a Manufacturer’s Award, but it was clear that more lightness must be added to keep the KH twins competitive. Thus Val Page designed a well-finned Lo-Ex silicon alloy cylinder block, with pressed-in iron liners retained by top flanges. As on the iron engines, pushrod tunnels were cast integrally with the block.

A deeply-finned Y-alloy cylinder head was also fitted. This was retained by one central stud (located inaccessibly, and needing a thin Meccano-type spanner to work on); plus eight right-through bolts, which screwed into bronze inserts in the head, and rotated in steel thimbles in the crankcase, to hold down the head and block. On each bolt, two out-of-step hexagons allowed 12 spanner holds per revolution, which aided tightening down.

The alloy head and its mostly elegant fixing method would be retained for the 1954-57 KH. In addition, the KHA, now known confusingly as the Huntmaster, the name of Ariel’s coming 650, uniquely (and perhaps after a look at BSA’s twins), had its rocker boxes angled so that the pushrods could be fed in from the top during assembly.

The new engine’s standard Lo-Ex pistons still gave compression of 6.8:1 for use with the 72 octane petrol then available in the UK, but with optional similar 7.5:1 pistons for 80 octane fuel. Thus equipped, and with 1952’s polished ports and combustion chambers, the KHA delivered between 26 and 28bhp, and a top speed of 93mph.

These engines went into Ariel’s twins for the 1952 ISDT at Bad Ausee in Austria, another tough one. Bob Ray was that year’s Trophy team Captain, but sadly there was to be no fairy tale result. At 5500ft above sea level, with wet, cold weather, a night run over a mountain pass with four miles of hairpins and three inches of slushy snow, was typical of conditions. For the Brits, morning starting difficulties, with thick oil turning to treacle, leaking petrol tanks etc contributed to defeat by the Czechs, back again after a couple of year’s absence due to the upheavals following the imposition of a 1948-on Soviet-backed dictatorship.

One redeeming feature of the event had been BSA’s truly impressive Maudes Trophy-winning effort on a trio of A7 Stars, with Gold Medals all round; though as Birmingham MCC entrants, the trio had not been subject to the more severe schedules for the top teams. Another was that neither Bob Ray nor his KHA-mounted companions Stan Holmes and W S G Parsons had lost any marks, and so took Gold Medals, and a Manufacturer’s Team Prize.

The 1953 ISDT, in Gotwaldov, Czechoslovakia, was to be the last ever where Britain’s team won the Trophy; though only just, thanks to the Czech Trophy team experiencing unexplained ignition problems. Both British teams were again twin mounted, with the exception of David Tye’s 350cc Gold Star. Bob Ray on a KHA had stepped down to head a Vase team with Ted Usher’s Matchless and Don Evans’ Royal Enfield, but fierce handicapping plus an initially wet track meant that in the Speed Trial, they came second to the Czechs. But, again, Ray was awarded a Gold Medal, and Ariel a Manufacturer’s Team Prize.

The following year in Wales, Ariel, along with BSA and others, reverted to singles. But the Czechs, with professional, co-ordinated training and preparation, won both Trophy and Vase. Ray rode one further ISDT making eight in total, before retiring in 1958 to run a chain of motorcycle shops. But the 1950 to 1953 ISDT twin era, to which his stylish riding had contributed so much, had been a truly heroic endeavour.

Meanwhile Ariel’s director Ted Crabtree had died tragically in a March 1953 car accident. The men with whom BSA, Ariel’s parent company since 1944, had replaced him, Bert Perrigo for a while and Ken Whistance as MD, scrapped the 500 twin’s expensive alloy barrels; with just 450 KHAs produced, out of a final total of 13,700 Ariel 500cc twins. For 1954 they introduced the badly-needed Huntmaster 650 (the KH became the Fieldmaster) – even if its engine was a restyled, lightly modified A10, in an equally timely new swinging-arm chassis. Sales soared and the Page 500, now yesterday’s man despite its virtues, was discontinued after 1957.

four-gallon tank, plus Ariel’s patented screw-down

petrol cap.

electronic one, but not yet needed to connect it.

its dry clutch. Note also fixed bare-metal footrest.

Tribute

Ariel’s ISDT twins had featured the Anstey-link frame, as did the 1953 KHA roadster for its one year of production. At least one of the other alloy-engined bikes built up by Bruce Sims is Anstey-link framed. And there are no external trappings like number boards or air bottles (another club member is rebuilding one of the actual ISDT machines, fully equipped). But Dave’s rigid bike is certainly true to the ISDT spirit, where lightness, reliability, plus a responsive engine with a fair turn of speed were the vital features.

Starting the special proved to be a knack. I also experienced some difficulty getting into first due to the footrest, a fixed cross-hatched bare metal bar, being mounted close to the gearchange pedal. After that, the Burman box, never Ariel’s finest feature, did produce some unwanted neutrals. But once underway, the overwhelming impressions were, firstly, the rigid Ariel’s excellent handling and roadholding, with surprisingly little discomfort penalty for the lack of rear springing on Oxfordshire’s lumpy roads; and predominantly, the free-revving nature of the 498cc engine. The only downside was its alloy-amplified clattering, soon drowned by the throaty roar from the single short silencer.

The engine, as Dave had advised me, certainly liked to be revved, and I was happy to continuously oblige, partly because I didn’t yet trust the tickover. The seven-inch front brake, despite its black paint job, performed poorly, but the rear anchor was good and together they worked effectively. The ride was characteristically comfortable thanks to Ariels’ well-developed ergonomics, and the competition-bred turning circle in the lanes was truly impressively tight. On the open road the noticeably light plot felt increasingly happy, accelerating joyously in third and top in a positively zippy fashion, with 60 coming up smartly.

I was reminded of another 500cc twin produced for one year only and involved with the ISDT, Triumph’s 1973 TR5T Trophy/Adventurer. It was 10lb lighter and with a few more horsepower than this Ariel – but the KHA special was as exhilarating to ride on road as a well-sorted oil-in-frame Triumph Trophy (see TCM, January 2022) from 20 years later.

For both, the defining combination was the lightness and the free-revving power. No wonder Dave puts the miles in on this one.