At one time all motorcycling was an adventure, but as roads improved the adventurous had to look elsewhere…

Words: Tim Britton – Pics: Mortons Archive

There is little doubt adventure biking has taken hold of public perception and big trail bikes are part of many makers’ ranges as enthusiasts clamour for machines which emulate the Paris Dakar mounts thrashed across remote desert regions.

There is even a series of challenges run by BMW which take riders of such adventure machines all over the world.

Of course many such machines never see the off-road world but the very attributes which make them suitable for demanding terrain make them extremely useful around towns and highways in normal riding.

Look back into history a little though, and the adventure thing has provided a lot of valuable publicity for motorcycle factories, and in some cases created a market for which they had to create a machine to fulfil. Or possibly, enthusiasts had recognised the alternative potential in a machine and suddenly its maker had to play catch-up.Of course in the strive for publicity, motorcycle manufacturers are not averse to producing one-off machines or adapting what was in the range, but what brings the most value is where ordinary production machines are achieving these remarkable feats.

Take the 1952 ISDT and Maudes Trophy event as an example, BSA hauled three production A7 twins from the assemblyline, rode them all over northern Europe,did the ISDT and rode home again on machines lightly modified, but clearlywhat was on the showroom floor.

In 1960 this would still be fresh in corporate minds and the BSA group now included Ariel who had the futuristic Leader and Arrow models – while not exactly sticking on the showroom floor they weren’t flying out the door either.

At that time Ariel’s top man, Ken Whistance, was always looking out for ideas to gain publicity.

Though increasing sales of the two-stroke were of paramount importance, so was publicity for the other 250 in the group, the C15.

Why? Well there had been a change in the motorcycling law and learner riders were now restricted to motorcycles of under 250cc and perhaps a demonstration of what these 250s could achieve would be in order. After all, BSA had pinned its off-road hopes on the 250cc unit construction machine.

Anyway, I can picture the scene in the higher echelons of the managerial strata at BSA as Miller is sent for: “Ah, Miller, we need a bit of publicity for the Arrow. Haul one out of production, check it over and pop up to Scotland to ‘do’ Ben Nevis. Tell you what, take that Smith chap and his C15 with you. Still here?”

I don’t know if that’s how it went, though Sammy did admit the idea was Ken Whistance’s. “He was always looking for publicity and I thought I’d get a chance to ride the bike in the Welsh too.”

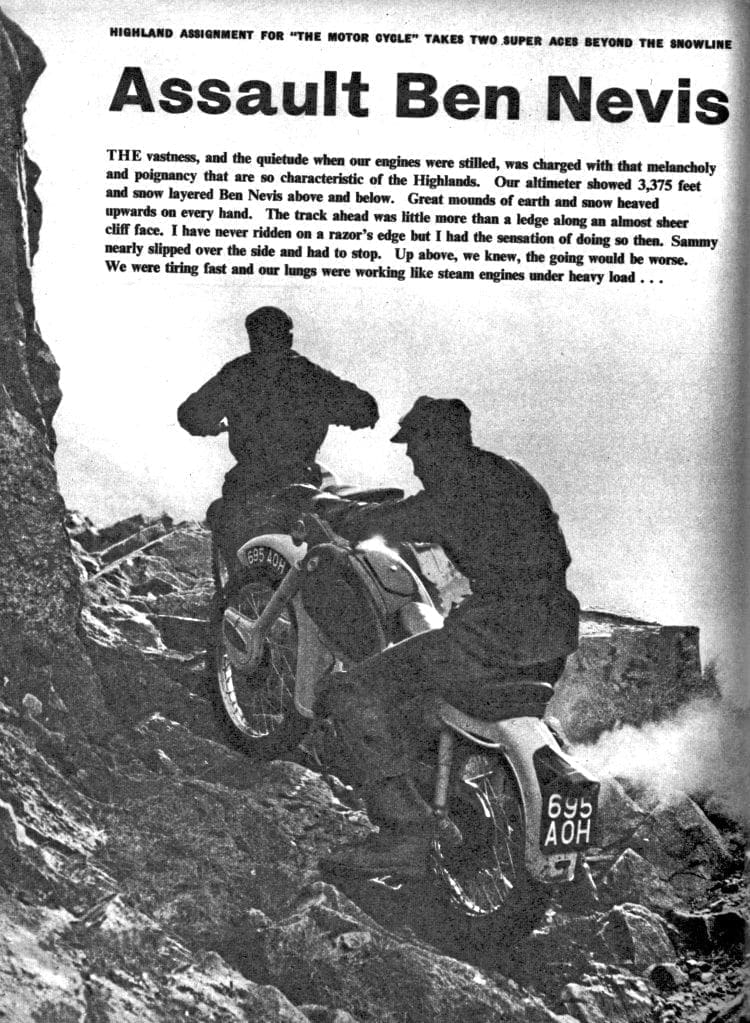

The Motor Cycle followed the attempt and Jeff Smith penned the feature around it and it’s his words I’m using for the background to this article.

Initially the idea had been to ride the drover’s track which forms part of the Moidart route of the SSDT, but with it being so close to the sea the snow had all but gone by March, so the next thought was Ben Nevis, leaving the drover’s track to January.

Looking at Ben Nevis it was obvious there would be plenty of snow to test the two lads and Jeff was quite straightforward about it that no one expected them to scale the summit of Ben Nevis at that time of year. Rather they were expected to get as far up the mountain as they could.

Given what both Miller and Smith were like in their personal preparation, their machines would have been looked over very carefully.

In Jeff’s case the C15 was his factory trials mount and all he did was add a scrambles rear tyre but Sammy had reverted to privateer status at the end of 1959 when his employers ceased four-stroke production and pinned their hopes on the two-stroke range.

Still, Miller had access to the full range of spares and knew what was needed so made a siamesed exhaust with an upswept pipe for the bike, moved the footrests further back, lowered the gearing considerably, fitted a larger diameter front wheel and fitted trials tyres to each rim.

Once in Fort William the pair got together with photographer Ian MacDonald and discussed the attempt, MacDonald wisely was to head up on foot.

The talk in the hotel was of how far they could actually get. On leaving the hotel the next morning the pair went to the shores of Loch Linnhe first. Why?

Well they had an ex-WD altimeter with them and Loch Linnhe is a sea loch so they zeroed the instrument there and this would give them some indication of what height they were at.

For those not familiar with Fort William, the route to Ben Nevis lies along Glen Nevis and the mountain overlooks the town.

The ride along to the start of the mountain track was apparently quite pleasant with hedgerows already starting to sprout and thereby hangs the rub with such northern climes.

This pleasantry is deceptive and the weather can change in an instant and Ben Nevis has snow on it 12 months of the year. Such changes in conditions catch many people out and even a walk up Ben Nevis is not to be taken lightly.

Once on the lower slopes of the mountain proper, the weather did change and drizzle dampened the two riders. There are recognised routes up Ben Nevis and tracks to follow and it was on one such path the lads set off to ascend Britain’s highest peak.

To two trials riders of their ability the path wasn’t difficult and they reached 500ft relatively easily. By 600ft even they were sweating heavily and footing their way round hairpin after hairpin bend. The physical exertion meant taking off a layer of clothing but keeping jackets on as they reasoned it might be colder at the top.

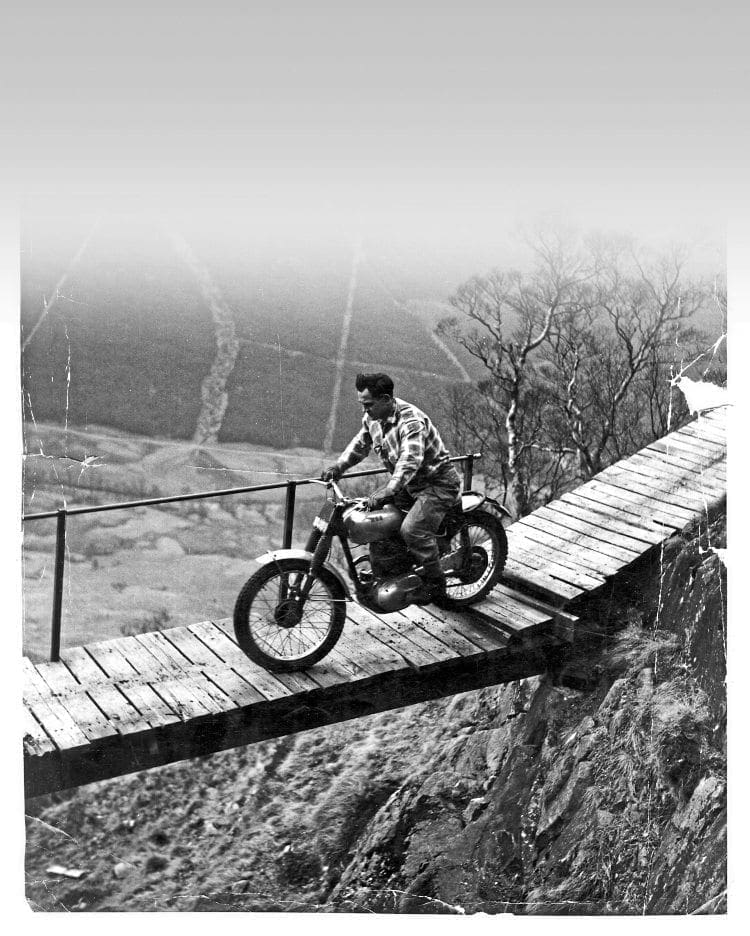

The first really testing obstacle was at 750ft, an old bridge of planks with a large step before it. Planks are very slippery when damp, trust me, it’s akin to hitting black ice.

This obstacle proved to be a breather, as for the next 200ft of altitude things were relatively easy. Then they weren’t!

The ravages of harsh weather had broken the path completely and it took riders 20 minutes to haul their bikes over this section but then progressed speedily to the next hazard.

Photographer Ian had to help haul the bikes up a 15ft step as they anxiously watched the weather turn.

Clouds were dropping, snow was visible and Smith’s C15 died. Thankfully nothing more major than forgetting to turn the petrol back on after the haul over the step.

Miller headed off unaware Jeff had stopped and when he caught the Irishman up he was inspecting a hazard which looked likely to end their climb.

Both men had the distinct feeling they’d been riding up a rock stream for some distance and when presented with a raging waterfall their fears were confirmed.

The altimeter said 1800ft, less than halfway up. They resignedly turned round and saw the photographer frantically waving at them – they had been riding up a stream and the track was over there. Back on track they made good progress to 2050ft where they were halted by an old iron bedstead straddling the track… that was some determined fly-tipper.

The task became more serious as patches of snow were being encountered and the temperature was falling.

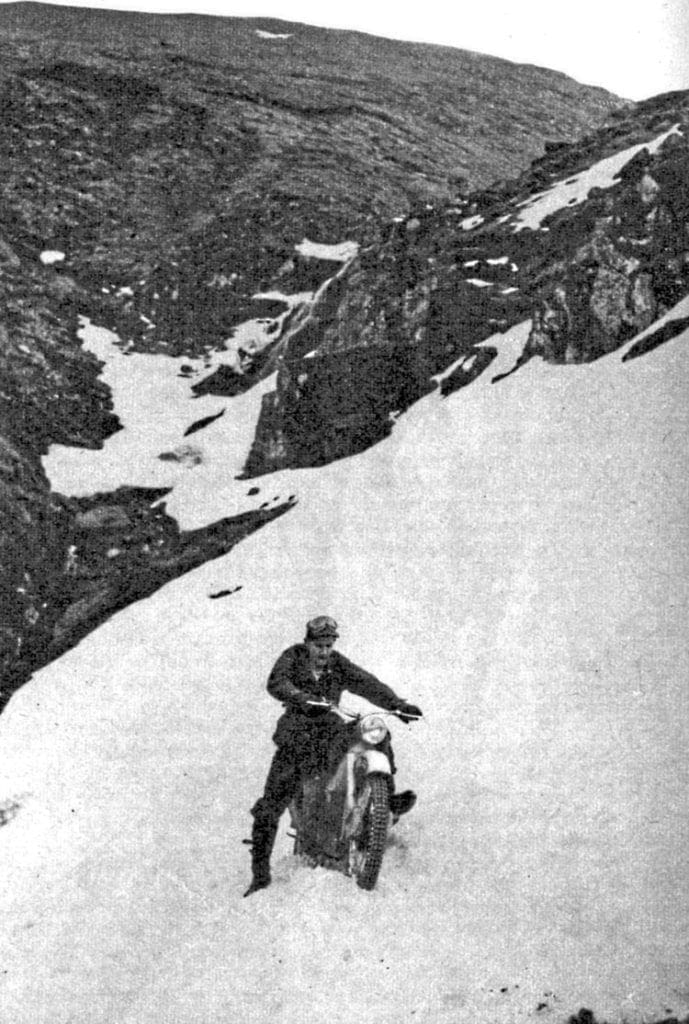

With a great white blanket laying across their route, their only chance was to stomp a path in the snow and force their machines across. The answer was speed and both Miller and Smith rocketed across the snow before they could sink in.

More snow was encountered at 2850ft and it took all three to heave each machine over the white stuff.

Now they began to be concerned, it was almost 1pm, the weather changed again and where they had enjoyed a brief spell of sunshine now it was bitterly cold and the cloud had descended but the wind had also cleared some snow away from the edge of the track and they rode on a razor edge between the drop on one side and deep snow on the other.

Suddenly they were in deep snow again, ahead lay a clear path and they tried treading a path but this was softer stuff and it took nearly an hour to force their way through.

The altitude was making breathing harder, the exertion was making them sweat more but a clear stretch ahead encouraged them to reach 3650ft but it had taken its toll on the admittedly superfit riders.

They attempted a few more feet with their bikes but no, it was not to be, they left their bikes there and trudged to what they thought was the summit another 400ft up.

Then the clouds parted and across a small valley was the true summit. It was as if the mountain wanted to say ‘I’m in charge here mere humans’ and at just over 4000ft – albeit that last few hundred on foot – they reluctantly turned back.

The descent was easier and faster though no less dangerous and by the time they reached the valley it was dusk and their 14-mile journey had taken seven-and-a-half hours.

As they headed back to the hotel both Miller and Smith reflected on the day with Jeff claiming it one of the most memorable he’d experienced.

Bikes on the run

There have been a considerable number of vehicular attempts to scale the mountain since the first recognised ascent in 1911 by a model T Ford driven by Henry Alexander jnr, of Alexander Motors in Edinburgh – Ford dealers and provider of the Alexander Trophy for the SSDT.

It also seems there have been numerous successful attempts by motorcycles to scale Britain’s highest mountain, the first being an AJS outfit in 1913. However, these days thanks to the enormous amount of money being spent on the mountain access for walkers, those who administer the mountain are not keen on motorised ascents.

1911……….Model T Ford

1913……….AJS outfit

19??………..Raleigh solo

19??………..Francis-Barnett solo

1928……….Ford Model A

1928……….Austin Seven

1930……….Ariel Colt 248 solo

1962……….Austin Champ

1963……….Land Rover

1971……….Three Wheel “Gnat”

1982………..Renault Van… halfway

1984………..SWB Land Rover

1984………..First recorded mountain bike ascent

Moto Scotland

There is a great place to go adventure biking in Scotland and the way to do it is to contact Moto Scotland.

CDB popped in for a day with Clive Rumbold at MotoScotland and thoroughly enjoyed the training experience on the Duke of Argyll’s Highland estate (all 50,000 acres of it), at Inveraray on the west of Scotland.

The courses, run by Clive and his wife Donna with a team of ACU qualified instructors, can be tailored to riders’ needs from complete novices who want an introduction to off-road riding to experienced adventure riders and anything in between.

Okay, what do you get for your money? Well, the groups are small so there is plenty of one-to-one for newcomers and even the editor of CDB learned new stuff despite 42 years’ active off-road riding.

You’re issued with the latest trail bikes, and the package includes fuel, insurance, riding kit, lunch and refreshments. Oh, and you get to see some fabulous scenery too.

Typically the estate provides moorland, forestry, dirt roads and tiny tracks to ride on. If you have a particular riding issue you wish to have addressed or want advice on how to overcome it, then it is as simple as telling Clive so this can be incorporated into your course.

There are a number of excellent places to stay in while you experience the off-road thing and CDB stayed in the Inveraray Hotel which was excellent.

Actually the accommodation thing is all part of the experience and is as important as the riding.

In order to join in on MotoScotland you need a bike licence or at least a CBT and plenty of enthusiasm, plus you must be prepared to be hooked on off-road.

Check MotoScotland’s website:www.motoscotland.com for more information or drop an email to Clive on [email protected]

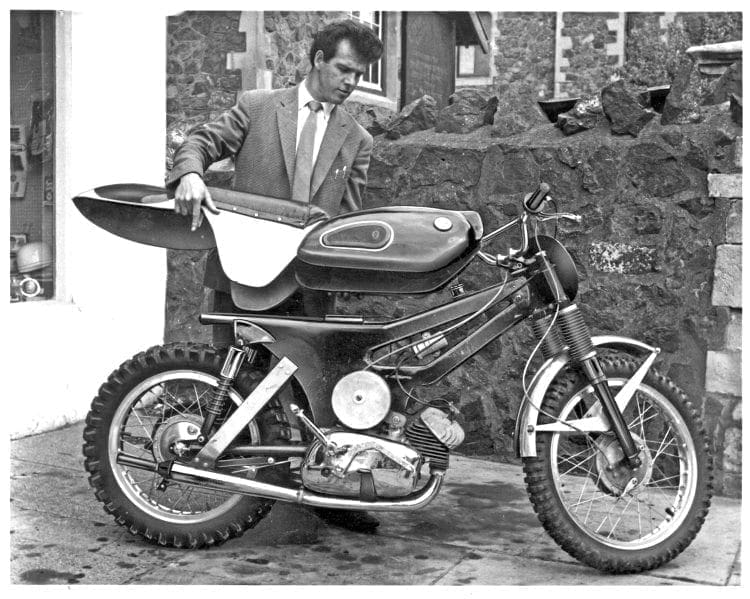

Street Scrambler

If you’re associated with a certain marque of motorcycle and your successes in trials are reported on a weekly basis while riding this marque and you need a runabout to get from your digs to the factory each day, then it makes sense to use one of your employer’s products.

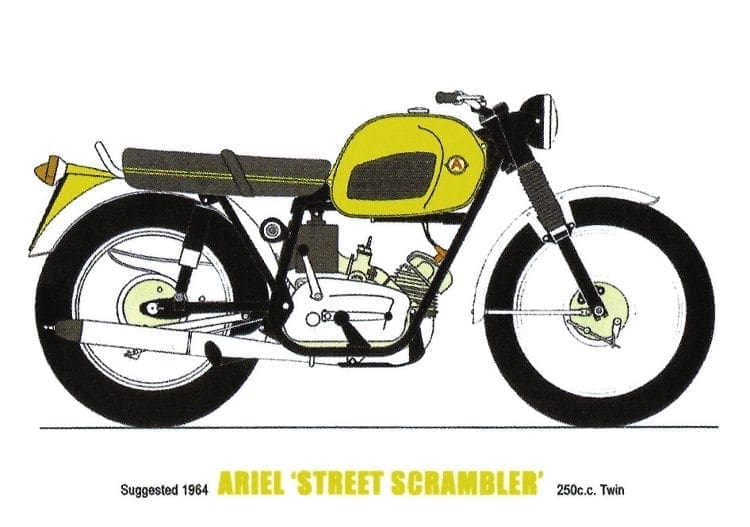

Such was Sammy Miller’s thinking when he put together a rather neat version of his employer’s two-stroke Ariel Arrow.

Except being Sammy Miller means you have your own ideas about how it should look.

He was familiar with the Arrow, our main feature is about him and Jeff Smith ascending Ben Nevis on a C15 and an Arrow, plus he rode the same bike in the Welsh Three-day Trial and had also raced one in the Thruxton endurance race. Not overly enamoured with the standard package, the Miller pencil came out and he drew a neater version with a conventional frame and forks.

Essentially a trail bike his runabout created quite a bit of interest with its Featherbed-style frame, BSA forks and proper tank.

While no one is pretending it would save the British industry it could well have brought some return on the investment Ariel made in the Leader/Arrow range.

However, it wasn’t officially sanctioned and apparently caused some embarrassment to those paid to come up with ideas.

So, while he was away promoting the company at the SSDT it was quietly cut up and chucked in the scrap bin.

To say Miller was aghast at the short-sightedness of such an act is an understatement.

Burton brewed

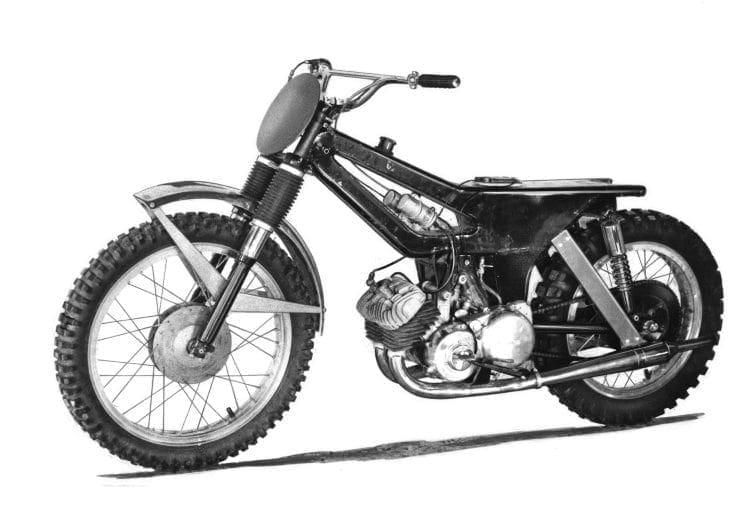

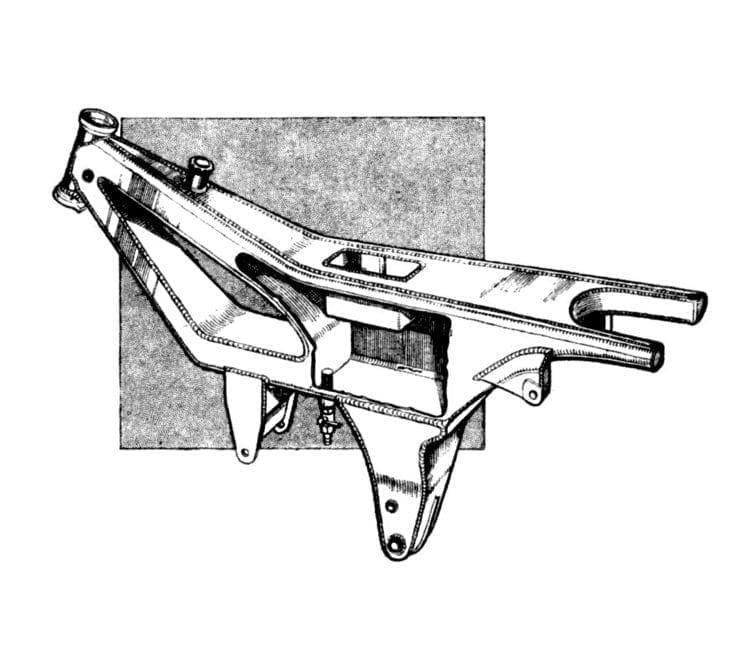

We doubt very much if the design brief for the Leader/Arrow range included ‘must be suitable for scrambling’ but that never stops anyone who fancies something different. Such a lad was Mick Burton, who at the time was based in Malvern – you still there Mick? – and he fancied riding an Arrow in scrambles.

These pics and drawing appeared in The Motor Cycle of July 1962 and show the level of thought Mick had put into this special.

The concept of the pressed steel idea appealed but the standard Arrow chassis wasn’t right so Mick folded his own from 16 gauge sheet steel, formed a fuel reservoir low down to aid weight distribution and dispensed with the Arrow forks.

In their place went a set of BSA C15 forks mated to an Arrow alloy hub, actually both ends have Arrow hubs and are also spoked to alloy rims.

Completing the Arrow look is a rather special one-piece dummy tank, seat and rear mudguard moulding made by a friend of Mick’s who cut the original apart, narrowed it and used that as a mould for this one.

The ignition was by battery and coil, the dummy tank unit lifts off after undoing one bolt and slackening two rear damper bolts so the battery can be speedily changed.

Tuning included packing the crankcase to increase primary compression, some port work and gearing. The project was described as ‘on-going’ but was certainly intriguing. Is it still out there?

Read more News and Features in the Summer 2020 issue of Classic Dirt Bike – on sale now!