All was set and sorted. But then, after some overnight contemplation, Speed Triple owner Stuart Wallace developed cold feet and things went disappointingly Pete Tong. ‘Sorry, I’ve changed my mind. I can’t let you ride it. It’s just too special to me, I can’t take the risk,’ was the general sentiment of his decline.

Having happily let me have a couple of goes on his Triumph previously, the reluctance came as a surprise. But after I’d applied the Mossy charm, eventually prised the key from him and had a quick spin, I fully understood why he’d been so protective. What a bloody great, classic, and endearing motorbike. If I owned it, I wouldn’t let any bugger have a go on it either!

It didn’t hurt that I sampled the sensual satisfaction delivered in spades by the iconic triple on a sunny afternoon, appreciating its numerous virtues along some fine, green-lined and sinuous routes in the Cotswolds. But wherever you ride it, there’s much to praise; its macho style, gorgeous exhaust note, fluid drive and secure handling being key factors. But really, it’s the sheer emotive power and character of the Brit bike that seals the fulfilment.

I have to admit to having some pretty special memories of this, the original Speed Triple Triumph model. I raced one (well, wobbled round at the back trying to keep up with the rest anyway) in the eponymous race series back in 1995. And riding that same bike all the way down to Paul Ricard to compete in a support race to the 24 hour Bol D’or, and then all the way back to race at Mallory the very next day remains the biggest achievement in my biking CV to date.

Memories in metal

Seventeen years ago may be a long time. Even so, thoughts of those special days soon came flooding back. The agricultural rumbling and rattling from within the chunky crankcases at tickover; the trademark hewn-from-granite styling, highlighted by the single round headlight and white faced clocks; the carbon wrap silencers glinting in the summer sunshine… all aided my more than contented reminiscence. But it’s the ride that’s the really special bit. Being aboard and under way pumps joy juices to parts not all other bikes can reach.

Stuart has modded his Trumpet in a couple of key areas and I definitely saw the sense and advantage in his post-Hinckley tinkering. It’s a weighty old beast by current standards, despite being built in an era when kilo-saving seemed to be a priority. But the greater leverage offered by his neatly-fitted sit-up-and-beg bars lets you muscle the bike more easily through corners, providing a greater chance to savour more of the bike’s stable and neutral handling. Getting it to turn now needs just a persuasive nudge rather than a full-on heave. The opportunity to haul it up from its sidestand with less risk of a hernia is also beneficial.

Purists may scoff at the removal of the original clip-ons, citing their absence as a style crime on any cafe racer. But believe me, the burden-beating higher bars on Wallace’s bike make it significantly easier to live with. Besides he’s done the job so well, it looks like it’s been factory-fitted anyway. The only slight downer is that it can get pretty damned windy at speed thanks to the bolt upright crucifix-enforcing riding position. My lengthy UK-France-UK trip might well have been a lot less comfy for my upper body with this arrangement.

The second notable alteration on the Speed Triple, and one that’s also instantly appreciable, is the work done on the suspension by Maxton. With a shock, and one of its fork kits installed, the ride of the Triumph is much improved. The sort of support and compliance they offer at both ends instantly reflects the higher spec of the internals.

Squatting under power, and dive on the half-decent brakes is much more controlled, but not at the expense of any loss of ride quality. Bumps are dealt with nicely without any of the relatively harsh feel the standard arrangement can sometimes transfer though the bars and seat. The Maxton mods effectively give the tyres more grip over rougher roads too, as well as providing the bike with a more up-to-date feel.

That’s not so true of the modestly performing motor, but that’s no bad thing. A prize asset of the bike, even though its sub 100bhp peak power figure might not generate too much excitement these days, the usability of what it has is a real advantage. The triple’s unhurried and flexible delivery creates speed from little effort, requiring minimal input from the rider. High revving via multiple gear-changing or big throttle openings are not an obligation.

There’s no harm ‘giving it some’ to hear the lovely music from those end cans from time to time, but doing it too often just doesn’t seem cool. Strong from idle upwards, with no peaks to chase or dips to avoid, the dependability of drive stays constant. It’s a welcome reliance, and regularly brings smiles of achievement, along with plenty of pleasure.

Riding the Speed Triple might well have reminded me well of a significant personal bygone age. But I suspect even if I’d never ridden one before, the encounter with the character-laden Triumph was enough to gladden me — it certainly made me content enough to want to own one.

It’s a bloody marvellous machine that’s as British as cod and chips and a pint of Best and just as satisfying to sample. No wonder it’s become such a collectable piece of Great British history. And no wonder owners aren’t always keen to loan them!

SPECIFICATIONS

ENGINE: 885cc, liquid cooled, 12-valve, dohc, in-line triple

MAXIMUM POWER: 98bhp @ 9000rpm

MAXIMUM TORQUE: 61lb-ft 6500rpm

TRANSMISSION: Six-speed

FINAL DRIVE: Chain

FRAME: Steel tubed spine

SUSPENSION: Front: 43mm telescopic forks, fully adjustable

Rear: rising-rate monoshock, fully adjustable

BRAKES: Front: twin 310mm discs with four piston calipers

Rear: single 255mm disc with twin piston calipers

TYRES: Front: 120/70 -17

Rear: 180/55 -17

SEAT HEIGHT: 790mm

WHEELBASE: 1490mm

DRY WEIGHT: 209kg

FUEL CAPACITY: 25 litres

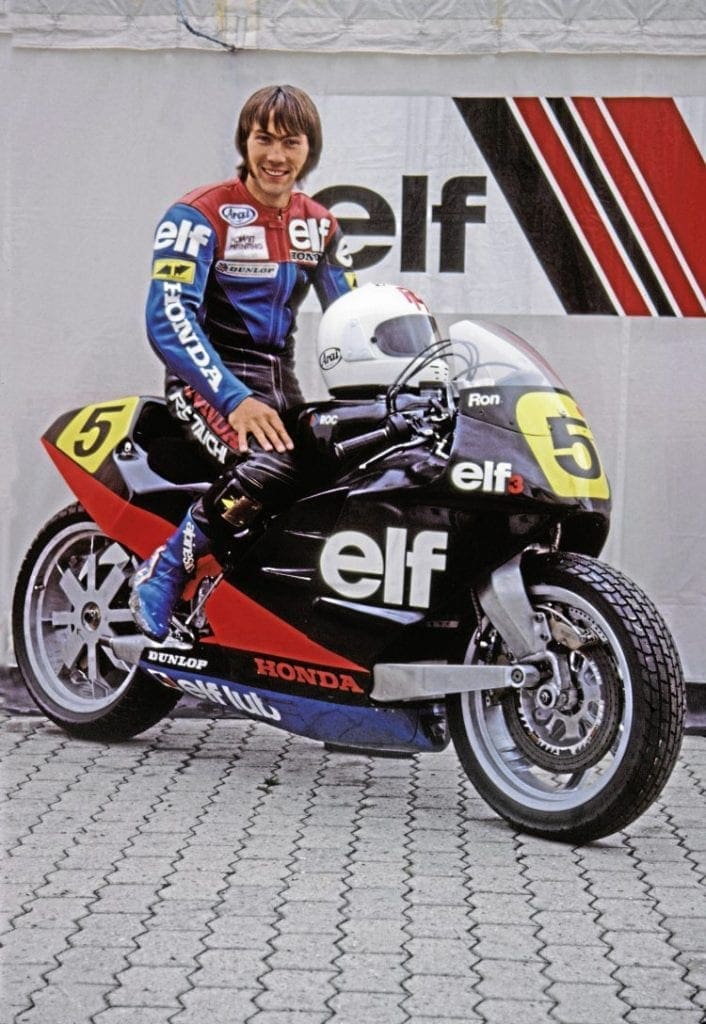

RON HASLAM

Former GP star, Ron Haslam knows a thing or two about Speed Triples. Having won several races in the 1995 Triumph Speed Triple Challenge series, the 57-year-old remembers the bike well.

“It was an enjoyable bike to race. We had to modify it to make it turn better but once that done it steered quite nicely, and could be ridden really hard.

“We ground off the heavier section of the coils at the top of the fork springs to increase sag, and then adjusted it with spacers. With a longer Öhlins shock the overall attitude of the bike was changed to drop the front end and put more weight over it. The forks were a bit basic, so we put heavier oil in them to increase the damping. Though they needed two to three laps to warm up and work at their best.

“The Triumph was a little bit heavy, as all road bikes are. But the power was really smooth, the brakes were good. There were some engine reliability problems with big engine bearings going, but that got better in time. As a precaution we changed our shells every other meeting.”

Words: Chris Moss

Photos: Mike Weston