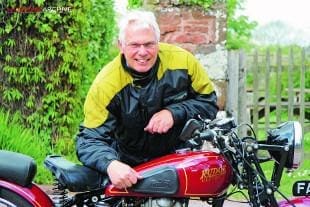

You’d expect a design and technology teacher to appreciate the finer points of engineering, and John Crispin traces his interest in things mechanical back to a specific machine that fired his youthful imagination, in 1967. “I remember well, I was in my teens looking at my first Rudge Ulster, with its brazed frame joints and a bronze cylinder head that was a work of art in itself, thinking that it was 20 times the quality of anything else I’d ever seen,” he recalls with evident enthusiasm. John bought that bike for £10 as a basket case, which was exactly what he wanted. “I had enough bits to assemble a complete motorcycle, while putting into practice everything I’d learned about Rudges in Phil Irving’s book, Tuning for Speed,” he grins.

Thirty-two years later, John was on the verge of retirement from lecturing and so was able to turn his attention to a second Ulster restoration, though this time with the benefit of greater technical skills and experience. He accepted a complete 1938 bike in exchange for a scale model of Graham Walker’s 1930 Senior TT mount. Walker had come second in that memorable race on his four-valve Rudge and had also taken third spot in the Junior TT on a radial-valve prototype, prompting a grateful sponsor to commission six replicas from a specialist model-maker in Regent Street, London. “It was 27in long with lovely detailing and rubber tyres,” says John, “and it was certainly a hard decision to let it go, especially as it was a gift from my father. But I decided that I would rather have a full-sized Rudge that I could use on the road as well as admire.”

Walker’s earlier victory in the 1928 Ulster Grand Prix, at an average speed over 80mph, had prompted him, as the Rudge-Whitworth Company’s sales manager, to bestow the Ulster name on a sports roadster. Early versions had a pentproof cylinder head with narrow valve angles, similar to the racers. This was replaced for 1932 with a radial layout, changing to semi-radial thereafter. Rudge placed great store by its racing success, which Graham Walker extended by syndicating the race team after the Coventry firm called in receivers during 1933. The following year, Rudge designer George Hack switched from using a cast iron cylinder head to bronze, which was fashionable for racing at the time due to superior thermal conductivity, though it carried a weight penalty. Following the death of founder John Vernon Pugh in 1936, the company’s assets were sold to the Gramophone Co. Ltd. (soon to become EMI), which re-launched the Ulster with enclosed and pressure-lubricated valve gear a year later.

Walker’s earlier victory in the 1928 Ulster Grand Prix, at an average speed over 80mph, had prompted him, as the Rudge-Whitworth Company’s sales manager, to bestow the Ulster name on a sports roadster. Early versions had a pentproof cylinder head with narrow valve angles, similar to the racers. This was replaced for 1932 with a radial layout, changing to semi-radial thereafter. Rudge placed great store by its racing success, which Graham Walker extended by syndicating the race team after the Coventry firm called in receivers during 1933. The following year, Rudge designer George Hack switched from using a cast iron cylinder head to bronze, which was fashionable for racing at the time due to superior thermal conductivity, though it carried a weight penalty. Following the death of founder John Vernon Pugh in 1936, the company’s assets were sold to the Gramophone Co. Ltd. (soon to become EMI), which re-launched the Ulster with enclosed and pressure-lubricated valve gear a year later.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

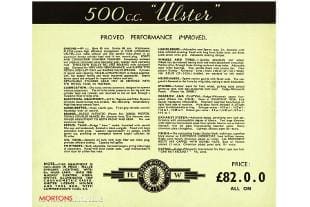

Production moved to Hayes, Middlesex during 1938 and a bold advertisement in the 14 April issue of The Motor Cycle appeared to herald a new era of competition glory. A whole page was left blank, save for a two-line statement in ordinary type that read, “At the Brooklands Clubmen’s Day on the 2nd April, Rudges took six firsts.” Southern dealer Glanfield Lawrence claimed in the same issue that Rudges were ‘…designed and built to give consistently high performance in the hands of average users.’ Nevertheless, with a retail price double that of many rivals, there would have to be something very special about a machine that could transform a good rider into an exceptional one, on road or track.

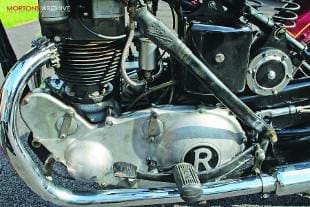

The heart of Rudge performance was that unique cylinder head and John shows me the internal workings of a spare 1939 engine in his workshop. A branched long rocker operates both inlet valves, while a short rocker acts directly on the offside exhaust valve and then links via an intermediate rocking couple to a remote rocker for the nearside exhaust valve. Rudge adopted four valves to cure a tendency for the stems to snap off, a lighter reciprocating weight allowing higher revs without valve float, and the late-model layout of two parallel and two radial valves has since appeared in more than one design of Honda engine.

The heart of Rudge performance was that unique cylinder head and John shows me the internal workings of a spare 1939 engine in his workshop. A branched long rocker operates both inlet valves, while a short rocker acts directly on the offside exhaust valve and then links via an intermediate rocking couple to a remote rocker for the nearside exhaust valve. Rudge adopted four valves to cure a tendency for the stems to snap off, a lighter reciprocating weight allowing higher revs without valve float, and the late-model layout of two parallel and two radial valves has since appeared in more than one design of Honda engine.

An intelligent approach to engineering was no less evident in the Ulster’s cycle parts. The large hand lever on the nearside was a patented centre-stand operating device that was a huge improvement, for all its complexity and weight, over the drop-down wheel stands common to other machines at the time. Coupled brakes gave balanced deceleration from the foot pedal via a cable running to an adjustable coupler on the fork leg, with a spring-loaded compensator to avoid progressive rear-wheel bias, for example while the rider was indicating right. Tommy-bars permitted quick release of the rear mudguard, while alternate flanged bolts and spigots, developed for ISDT models, allowed rear wheel removal without disturbing the brake drum and sprocket.

The engine on John’s example came with a later alloy cylinder head, possibly because the bronze heads fitted prior to 1939 were prone to cracking between the spark plug hole and the exhaust valve seats. He has now fitted the correct bronze head with a special adaptor for a 14mm long-reach spark plug. Most of the other parts that came with the bike seemed to be in serviceable condition and were evaluated with the benefit of expertise from the Rudge Enthusiasts’ Club during the assembly stages.

The engine on John’s example came with a later alloy cylinder head, possibly because the bronze heads fitted prior to 1939 were prone to cracking between the spark plug hole and the exhaust valve seats. He has now fitted the correct bronze head with a special adaptor for a 14mm long-reach spark plug. Most of the other parts that came with the bike seemed to be in serviceable condition and were evaluated with the benefit of expertise from the Rudge Enthusiasts’ Club during the assembly stages.

John could not resist the opportunity to improve on even George Hack’s meticulous engineering as the otherwise straightforward restoration neared completion, during 2002. He modified the oil flow from the brass pipe that lubricates each rocker spindle, to ensure good pressure along its length. He also cut a hole for a Triumph inspection cap and breather atop the nearside exhaust rocker box, since access to check the valve clearance would otherwise involve part-removal of the engine. A new plunger valve prevented wet-sumping from the oil tank feed pipe, but John added an alloy collar to hold the valve open and this fitted over the main fuel tap at rest, as a reminder that the oil supply was disconnected.

Further non-standard items made the bike more suitable for regular use on modern roads. A BSA Gold Star piston, with the benefit of an oil control ring, reduced a tendency to seize on long runs, though its different-shaped piston crown slightly lowered the compression ratio to 6.5:1. A sealed suspension unit with black spring coils, from a limited-production batch made to special order by Hagon Products (0208 502 6222), added progressive damping and an adjustable spring rate to the girder forks. A halogen headlamp bulb made the most of six-volt electrics and a later Lucas stop lamp supplemented the Miller original, while a solid-state voltage regulator fitted discreetly between the oil tank and battery box.

Further non-standard items made the bike more suitable for regular use on modern roads. A BSA Gold Star piston, with the benefit of an oil control ring, reduced a tendency to seize on long runs, though its different-shaped piston crown slightly lowered the compression ratio to 6.5:1. A sealed suspension unit with black spring coils, from a limited-production batch made to special order by Hagon Products (0208 502 6222), added progressive damping and an adjustable spring rate to the girder forks. A halogen headlamp bulb made the most of six-volt electrics and a later Lucas stop lamp supplemented the Miller original, while a solid-state voltage regulator fitted discreetly between the oil tank and battery box.

Eager to experience the Rudge for myself, I retard the ignition using the lever on the left handlebar and the pushrod engine fires with enough clatter from its complex rocker arrangements to sound like a parallel twin, though its pair of silencers mutes the exhaust noise effectively. A small brass plunger extends from the timing chest to indicate a healthy oil pressure, the adjacent lever being a secondary decompression device. The gear action is one up and three down, first gear seeming very low, with a big step between third and top. The gears require time to engage, each selection slowed by an external linkage behind the steel gearbox outer cover, but the engine is so eager to rev that I leave it in third gear most of the time.

I head south on the old B3181, which was formerly the main road to Exeter before the M5 was built and now runs parallel to the motorway. One of the reasons that John moved to Devon from Surrey a year ago was to enjoy deserted roads like this and the Rudge excels in such territory, its four-valve engine eager to rev at all times. The Hagon suspension at the front end feels quite stiff, so I slacken the friction damping on the girder forks right off. The coupled brakes work well on these dry roads, pulling the bike down squarely and progressively, though the front brake is effective on its own.

I head south on the old B3181, which was formerly the main road to Exeter before the M5 was built and now runs parallel to the motorway. One of the reasons that John moved to Devon from Surrey a year ago was to enjoy deserted roads like this and the Rudge excels in such territory, its four-valve engine eager to rev at all times. The Hagon suspension at the front end feels quite stiff, so I slacken the friction damping on the girder forks right off. The coupled brakes work well on these dry roads, pulling the bike down squarely and progressively, though the front brake is effective on its own.

‘To my mind, an Ulster in the right hands should have the potential to surprise the rider of any contemporary twin-cylinder machine and this one comes in such a socially acceptable package that, when I pull up outside the wisteria-clad 16th-century Red Lion Inn at Broad Clyst, customers barely look up from their trestle tables in the spring sunshine.’

The Rudge is definitely no plodder and I am reassured by stable handling at speeds adjacent to the national limit. Although direct descendants of Rudge’s open-valve TT winners have more of a reputation for outright performance, this was barely contained by a relatively lightweight frame with D-section girder forks, so it is arguable that the later chassis makes for a far more practical road bike. To my mind, an Ulster in the right hands should have the potential to surprise the rider of any contemporary twin-cylinder machine and this one comes in such a socially acceptable package that, when I pull up outside the wisteria-clad 16th-century Red Lion Inn at Broad Clyst, customers barely look up from their trestle tables in the spring sunshine.

Second glances confirm that the bike looks handsome in red with gold pinstriping for its fuel tank and mudguards, this being a standard colour option of the time along with green, blue and the traditional black. Despite being in full public view, there is one more aspect of the machine that I must now try for the first time. Sitting squarely on the saddle, I reach down for the long handle by my left foot and find that the Ulster rolls easily onto its centrestand before I’ve begun to apply any real pressure. The mechanism works so well that it’s no wonder Vincent incorporated it into its final series of machines.

That the four-valve Rudge was no ordinary motorcycle is recorded in its historic race wins, and the Ulster was its ultimate expression as a roadster. Were it not for the production of radar equipment taking priority from the end of 1939, it is quite likely that a growing reputation would have secured Rudge’s future at the giant EMI factory in Hayes. John points out an irony that the quality of original engineering is now causing unforeseen problems for the Rudge Enthusiasts’ Club, the West Country section of which, he informs me, is well subscribed, although its members are more scattered than in the Home Counties.

That the four-valve Rudge was no ordinary motorcycle is recorded in its historic race wins, and the Ulster was its ultimate expression as a roadster. Were it not for the production of radar equipment taking priority from the end of 1939, it is quite likely that a growing reputation would have secured Rudge’s future at the giant EMI factory in Hayes. John points out an irony that the quality of original engineering is now causing unforeseen problems for the Rudge Enthusiasts’ Club, the West Country section of which, he informs me, is well subscribed, although its members are more scattered than in the Home Counties.

“As owners grow older, they tend to ride their bikes less and so they’re no longer wearing at a fast enough rate to justify the club holding a large inventory of spare parts,” he explains. “We need younger enthusiasts to follow in our wheel tracks by riding the things regularly and the best advertisement is to see a Rudge in actual use. I find that the main talking point for people under 45 is the twin exhaust pipes, which often leads into a discussion about four-valve heads and coupled brakes, both of which are generally thought of as modern inventions. So if nothing else, my Rudge is educating people about design and technology, which is why I bought one in the first place.”