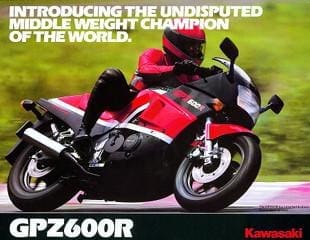

Everything was going for Kawasaki’s GPz600R when it was launched at the end of 1984. The factory was basking in the glory that it had created with the GPz900R, a machine that set new rules for superbikes. Like the 900, the 600 was liquid-cooled, the first of its type. It had Grand-Prix bike styling. Technology sprouted all over it. With the then-fashionable 16in wheels it looked tiny. And it was quick.

Yet reaction from the motorcycle world was lukewarm. Some had been expecting a smaller GPz900R, which soon after its launch a year earlier had proved its superiority with a crushing Production TT victory and become voted Machine of the Year. Others reacted to its nervous handling, a characteristic that would be applauded in sports bikes a quarter of a century later.

As it turns out, Kawasaki was far ahead of its time, perhaps too far. Two years later, it took Honda’s CBR600 to create a new category of motorcycle – the sports 600 – and despite the Kawasaki’s strong credentials it was almost immediately eclipsed. And it was, ironically, engine technology that was Kawasaki’s Achilles heel. It was almost as if Kawasaki’s engineers had been instructed to design a fabulously exotic sports 600, and then told that money was short for the engine because costs had been burned on the GPz900R.

Yamaha had shown the way when the FZ750 was launched at the same time as the GPz600R at the Cologne Show in Germany. The 750cc four used steeply downdraught inlet ports, a feature for enhancing volumetric efficiency employed in F1 technology that would be adopted by every factory in a quest for more power. This was used effectively by Honda on the CBR600. But in the GPz600R, Kawasaki used a development of the air-cooled four-cylinder engine from the GPz550, technology that had first appeared with the Z500 four in 1979. The GPz550 was a remarkable machine for its time, appearing in 1982, with a nimble chassis and lively 61bhp dohc power unit that delivered a top speed of 125mph or more. But there wasn’t much room left for further development.

Yamaha had shown the way when the FZ750 was launched at the same time as the GPz600R at the Cologne Show in Germany. The 750cc four used steeply downdraught inlet ports, a feature for enhancing volumetric efficiency employed in F1 technology that would be adopted by every factory in a quest for more power. This was used effectively by Honda on the CBR600. But in the GPz600R, Kawasaki used a development of the air-cooled four-cylinder engine from the GPz550, technology that had first appeared with the Z500 four in 1979. The GPz550 was a remarkable machine for its time, appearing in 1982, with a nimble chassis and lively 61bhp dohc power unit that delivered a top speed of 125mph or more. But there wasn’t much room left for further development.

Kawasaki’s adoption of liquid-cooling and a 16-valve dohc cylinder head was the right move, but it lacked the sophisticated porting that would enable much more than its 75bhp peak power to be achieved. Budgetary and therefore design constraints cramped its style. It’s true that, apart from one exception, the other manufacturers had still to take up liquid-cooling to better control engine heat at higher power outputs – Honda’s CBX550, Suzuki’s GSX550 and Yamaha’s XJ550 were still air-cooled – but Kawasaki could have stolen a march on all of them had it used a clean sheet for the GPz600R’s engine.

Only Honda’s novel liquid-cooled V-four VF500 – first appearing in 1984 – provided an indication of a route to take, but it was complex, expensive and unreliable. That’s a hindsight the motorcycle press at the GPz600R’s debut at Jarama in Spain early in 1985 wouldn’t have enjoyed. No doubt impressed by the presence of six-times road racing world champion Kork Ballington, they found the bike handled ‘brilliantly’ at high speed.

Ballington was quoted as saying, “Seems to me it has more in common with bikes like the Harris Magnum – you know, with specials and super-sports specials – than with production bikes.” Even though the South African had raced Kawasakis from his early days, it was a pretty measured comment.

Like the FZ750 Yamaha, the Kawasaki boasted a perimeter-style frame with rectangular-section steel spars running from the swingarm pivot, around the engine to the steering head. Spars dropped from the head either side of the engine under which bolt-on sections completed the loop. Following later trends it was shorter by two inches from the swingarm pivot to the steering head. With the slim fairing and bodywork mounted, styling attachments carried the line back to the rear fairing. With 16in wheels it was low and with a wheelbase of 56.3 inches, only slightly longer than the GPz550.

In Japan, a more exotic aluminium-alloy frame was used for the domestic-market’s smaller-capacity but otherwise outwardly similar GPz400R. Apart from additional side spars, this was an alloy version of the steel frame and reduced the bike’s overall weight from 195kg to 176kg. (As with Yamaha’s Japan-only V-four RZV500, the use of an aluminium frame was regarded as fragile and risky, and therefore safer to confine to the domestic market). Rear suspension on the GPz600R used an aluminum-alloy box-section swingarm with a single shock mounted low at the front and compressed by levers from the arm.

In Japan, a more exotic aluminium-alloy frame was used for the domestic-market’s smaller-capacity but otherwise outwardly similar GPz400R. Apart from additional side spars, this was an alloy version of the steel frame and reduced the bike’s overall weight from 195kg to 176kg. (As with Yamaha’s Japan-only V-four RZV500, the use of an aluminium frame was regarded as fragile and risky, and therefore safer to confine to the domestic market). Rear suspension on the GPz600R used an aluminum-alloy box-section swingarm with a single shock mounted low at the front and compressed by levers from the arm.

Up front, the telescopic fork offered some novel features. With 37mm stanchions, the springs were complemented by air that could be adjusted for load, though this was a dubious benefit and offered little variation in response. Despite only having single-piston floating calipers, the brakes were regarded at the track test as pretty good for the day, but seemed to lack feel on normal roads. Disc diameters were up by 10mm compared with the GPz550 to twin 270mm asymmetrically perforated rotors at the front and 250mm at the rear. Novel feature of the front end was the AVDS fork, which used valving to increase the damping at increased suspension travel and speeds.

An anti-dive system also used valves on the front of the legs which dramatically increased the compression damping under braking by using the brake hose pressure to trigger the valves. As with similar systems on other bikes of the time, the system added volume to the brake hydraulics serving only to make them feel spongier. Compact as the GPz600R was, it wasn’t uncomfortable. You sat in the scalloped seat, reaching across the wide fuel tank to the grips that with the controls were bolted to the top of the yoke. Some found the fairing too small to offer reasonable protection from wind blast, but I found it almost perfect for a racing crouch.

For Kawasaki’s midrange machines, the GPz600R marked a line dividing the factory from the seventies convention of duplex frames with 19in front and 18in rear tyres. The stiffness of the perimeter frame also allowed steeper steering geometry with a 63° head angle and less trail with 97mm. The GPz600R was also a departure from the GPz900R’s design that featured large-diameter frame spine that served well but would soon be ditched (unsuccessfully as it turned out) with the GPz1000RX.

The result was a chassis that could be hustled through high-speed sweepers more confidently than with the 550, the wider tyres gripping well, though not once they’d been thrashed and were wearing. Neither did ride quality have to be sacrificed: damping on the Uni-trak rear shock could be adjusted too. The front end geometry enabled quicker response in flicking from lock to lock, but the downside was in more nervousness at the less frantic speeds used in town for relaxed riding. While the 16in wheels would have aided turn in at speed they failed to aid stability when needed on damp surfaces. I was surprised to be caught out in traffic when I locked up the front end and came a cropper. Amen to the development three years later of more sophisticated tyre constructions and 17in sizes that provided a better compromise in handling.

The result was a chassis that could be hustled through high-speed sweepers more confidently than with the 550, the wider tyres gripping well, though not once they’d been thrashed and were wearing. Neither did ride quality have to be sacrificed: damping on the Uni-trak rear shock could be adjusted too. The front end geometry enabled quicker response in flicking from lock to lock, but the downside was in more nervousness at the less frantic speeds used in town for relaxed riding. While the 16in wheels would have aided turn in at speed they failed to aid stability when needed on damp surfaces. I was surprised to be caught out in traffic when I locked up the front end and came a cropper. Amen to the development three years later of more sophisticated tyre constructions and 17in sizes that provided a better compromise in handling.

Conveniences within the instrument cluster included gauges for fuel level and temperature, along with a volt meter in the speedo face that was activated by a finger button. Lifting the rear half of the seat, which can be replaced with a fairing, revealed bungee hooks and helmet locks. Starting on the button was reliable, but you needed to juggle with the mixture-enriching lever to prevent the revs racing with a cold engine. The GPz600R’s engine was patently an improvement on the 550, which with increasing peak power became less flexible. Willing and flexible with a light action at the grip, it pulled hard from as low as 2000rpm yet revved smoothly past the peak torque revs at 9000rpm and well past the peak power at 10,500 to the rev limit at 12,500rpm.

Saying that the GPz600R engine is based on the GPz550’s is a simplification, but this is probably because the 600 used the same crankshaft stroke of 52.4mm, the same primary drive with an inverted-tooth chain to a countershaft with gears to the clutch body, and the same internal ratios for the gearbox. Capacity was upped to 592cc by an increase in the cylinder bores from 58 to 60mm. The separate liquid-cooled cylinder block used wet cast-iron liners, differing from the 900R, and was bolted to the cases with 12 studs.

To provide more coolant space, the two inner cylinders each were moved closer by 1mm and this necessitated a crankshaft that was different from the 550’s. The coolant pump was driven off the left-hand end of the countershaft. An aluminium radiator used a thermostat-controlled fan. The double overhead camshafts ran in plain bearings and were driven from the centre of the crankshaft by a lighter inverted-tooth chain, controlled by a tensioner of the same design as the 550’s.

Another major departure from Kawasaki’s previous dohc design practice was the valve-train’s use of a rocker for each pair of valves (21.5mm inlet and 19mm exhaust), with clearance adjusted by screws and locknuts. Angles of the valves from vertical were 19° for the inlets and 17.5°, still short of modern practice in which the valves are more vertically orientated, further improving filling efficiency.

Other changes included a revision of the generator on the left end of the crankshaft. Subsequent practice was to drive the generator from a countershaft above the gearbox to reduce width, but in the GPz600R’s case the generator coils were on the cases and enveloped by the flywheel, reducing its width. Overall the engine was, at 455mm, 40mm narrower and 39mm shorter than the GPz550’s and, with the use of plastic end covers, 1kg lighter despite the addition of the cooling system. Yet with a gallon of fuel the GPz600R weighed 455lb, some 45lb more than the 1982 GPz550.

Other changes included a revision of the generator on the left end of the crankshaft. Subsequent practice was to drive the generator from a countershaft above the gearbox to reduce width, but in the GPz600R’s case the generator coils were on the cases and enveloped by the flywheel, reducing its width. Overall the engine was, at 455mm, 40mm narrower and 39mm shorter than the GPz550’s and, with the use of plastic end covers, 1kg lighter despite the addition of the cooling system. Yet with a gallon of fuel the GPz600R weighed 455lb, some 45lb more than the 1982 GPz550.

When Which Bike? magazine tested the bike at MIRA’s proving ground in the Midlands in 1985 in admittedly damp conditions, the extra power and improved aerodynamics still paid off. Mean top speed, an average taken of two runs in opposite directions, was 135.2mph, with the engine revving to almost 11,000rpm in top, indicating that the higher gearing than on the GPz550 was just about right. The equivalent speed for the GPz550 was 122.74mph, which I’d regarded as impressive three years earlier in 1982. Acceleration too was significantly better, despite the extra weight. Which Bike? recorded a mean standing-quarter-mile time of 12.13 seconds, a good 0.8 seconds better than the GPz550. Also suggesting that the GPz600R’s aerodynamics were impressive is the overall fuel consumption of 52mpg.

Kawasaki didn’t make many changes to the bike until the 1989 model year despite the launch two years earlier of Honda’s CBR600. With the ZX600A5 factory designation, The GPz600R’s compression ratio was increased from 11 to 11.7:1, lifting peak power to 80.4 bhp along with the torque which peaked at lower revs. Tyre sizes were increased in width. By then the factory had also introduced the GPX600 (ZX600C1 to C3), restyled to be similar to the GPX750, which used a slightly higher tuned engine than the ZX600A5, with 83.8bhp@11,000rpm.

It wasn’t until Kawasaki launched the completely revised ZZ-R600 in 1990 that the factory had a bike with performance and potential on a par with the competition. With a much shorter stroke engine and modern architecture (capacity was 599cc from dimensions of 64 x 46.6mm), revs were up again and power reached 98.6bhp. A new light-alloy frame and chassis with 17-inch wheels sorted out the overall handling. But Kawasaki was just catching up in a race that it should have applied itself to years earlier when it had the chance to establish itself as the middleweight champion of a class that had yet to be adopted by the other factories. The original GPz600R, though an advance on the air-cooled models, represents a missed opportunity to grab the limelight.

It wasn’t until Kawasaki launched the completely revised ZZ-R600 in 1990 that the factory had a bike with performance and potential on a par with the competition. With a much shorter stroke engine and modern architecture (capacity was 599cc from dimensions of 64 x 46.6mm), revs were up again and power reached 98.6bhp. A new light-alloy frame and chassis with 17-inch wheels sorted out the overall handling. But Kawasaki was just catching up in a race that it should have applied itself to years earlier when it had the chance to establish itself as the middleweight champion of a class that had yet to be adopted by the other factories. The original GPz600R, though an advance on the air-cooled models, represents a missed opportunity to grab the limelight.

Reliability

The GPz600R suffered few inherent reliability problems, according to Dave Marsden, who runs Z-Power, the UK’s leading source of parts and service for the early Kawasakis. “I can’t think of anything that stands out that was bad about them,” said Dave. “We have sold a few head gaskets and the odd carb diaphragm but nothing else springs to mind on the motor. The rear shock, fork seals and swingarm bearings wear, but no more than usual.”

The rear suspension linkage lacked greasing points, which meant that lubrication was neglected, and requiring complete disassembly for servicing. Some also say that the camchain adjuster fails, but this is often because of servicing neglect.

Also, the out-of-sight exhaust system corrodes, but which of them don’t at this age. It’s also reported that leaving the bike on the sidestand that when the bike is started from cold while leant over, the cam lobes can be starved of oil, leading to premature wear. Dave says that when the GPz600R appeared he was impressed by its handling. “After a decade of 19in front wheels I was overjoyed with the 16in jobbies,” he said. “I was starting to think all Kawasakis handled like a pig on stilts until the GPz came along.”