Some days nothing goes right. Even when I was fully employed doing The Best Job In The World (official), when several working days each month were spent pottering around the countryside aboard other riders’ Prides & Joy, there were off days. Days when it poured down. Days when my own bike broke down. Days when the test bike turned out to have been described by Proud Owner as something quite other than the shuddering leaking horror revealed by the first mile a-wheel. Days when you somehow managed to break Proud Owner’s P&J.

But there were also the good days. The day I spent riding this Sunbeam, the S8 seen here in glorious RealClassic electrocolour; that was a good day indeed.

Sunbeam was once a Big Name. Before WW2, Sunbeam’s singles were recognised as being probably the best finished bikes in the whole world – or in GB, which was then only a little smaller than the rest of the world. Sunbeam were so famous for their finish – or so the story goes – that ICI bought the entire company just so they could be privy to the secret of that lustrous finish. Oh yes? Oh well.

And after being owned for a relatively short time by the mighty Imperial Chemical people, the proud name of Sunbeam passed to Associated Motorcycles, the London concern which had been formed when the Matchless Collier brothers bought out the Stevens’ AJS marque.

Half-remarkably, AMC actually managed to produce a range of suspiciously AMC-like new Sunbeams, but their sterling effort at developing the name was brought to an untimely close by the onset of the 1939-45 conflict. By the end of that savage interlude, and despite the semi-mythical appearance of a slightly lumbering, but potentially promising, V-twin, AMC had sold the name of Sunbeam to BSA, who were a Brum-based company which built – among many other things at the time – BSA motorcycles. And BSA had A Plan.

Half-remarkably, AMC actually managed to produce a range of suspiciously AMC-like new Sunbeams, but their sterling effort at developing the name was brought to an untimely close by the onset of the 1939-45 conflict. By the end of that savage interlude, and despite the semi-mythical appearance of a slightly lumbering, but potentially promising, V-twin, AMC had sold the name of Sunbeam to BSA, who were a Brum-based company which built – among many other things at the time – BSA motorcycles. And BSA had A Plan.

BSA had decided that after the war they would build a gentleman’s motorcycle. This fine machine, they had also decided, should bear a Proud Name upon it prestigious petrol tank. That name, they sensibly decided, should not be BSA, which had quite possibly been over-used on the tanks of too many WD M20 sidevalves to be accepted – particularly by the legions of demobbed soldiers – as a Name of Quality. In short, BSA had decided to sell Sunbeams. (And in any case, they claimed to have bought the marque primarily for the Sunbeam range of pedal cycles, so the motorcycle connection was convenient.)

But no ordinary traditional Sunbeam were they to build. No, BSA decided that following victory, the world would be ready for that Motorcycle For Everyman. To quote their MD of the day; ‘a motorcycle as modern as tomorrow, but built in the famous tradition’. A motorcycle whose purchase would not be restricted to gritty-fingernailed fiends, but which would appeal to riders of more sophisticated two-wheeled tastes. The bike would be non-threatening in appearance, would boast car reliability, lots of smoothness, and absolutely no messy, noisy drive chains. So, demonstrating remarkable logic, BSA hired themselves a design engineer, one Erling Poppe, sat him down with an earlier BSA experimental engine (the ‘line-ahead twin’, from 1928) along with a captured ex-Wehrmacht BMW R75 or two, and instructed him to design a wholly-new motorcycle which was suitably super to be offered as the flagship of the BSA two-wheeled empire.

And so he did.

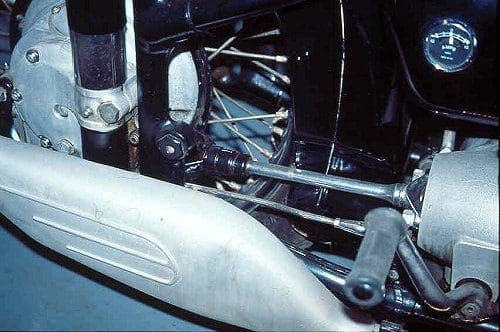

Erling Poppe designed a motorcycle which remains unique both in concept and execution, in terms of the British bike industry at least. The engine was a 487cc in-line, air-cooled twin, with all-alloy construction, an overhead camshaft and coil/distributor sparks. Power was transferred through a car-type clutch to a car-type gearbox, down a car-type final drive shaft and through a right angle to the back wheel. Nothing else offered by British companies looked even faintly like the Sunbeam, with its huge fat tyres, odd front fork and remarkably clean, of a piece styling. And as is the way with all too many truly bold ventures … no-one bought them.

There were loads of faults with BSA’s new baby Sunbeam, too. In these strange days, when so many ‘classic’ bikes are cossetted and treated mainly as objects of nostalgia and reverence, it’s easy to forget that when they were new, riders of these machines expected to be able to use them with as little care and consideration as might be given to, say, a Triumph Sprint ST today.

And those early BSA Sunbeams were a little less than 100% reliable. This was particularly unendearing when you consider that they were one of the three most expensive bikes on the UK market at the time!

The new bike was also slow; a top speed of around 75mph did not compare well with 500cc singles, never mind the other more conventional parallel twins which were rushing to join the post-war market. Its handling was strange to anyone used to more conventional British 500s; those wide-section sixteen inch tyres and four inches of ground clearance did not exactly place the Sunbeam in the gentleman’s scratcher class. And the brakes were a little feeble, as the S7 was pretty porky; 435lb was a lot for a 500 roadster of the period. In fact, as Steve Wilson pointed out in his most excellent British Motorcycles Since 1950; Vol 4, the Sunbeam was as heavy as a Norton Commando. Propelling that mass around in a spritely manner was asking rather a lot of a claimed 25bhp.

But worst of all … the bike looked strange. Consumer taste can put up with a lot, but motorcyclists have long been a conservative bunch (and before you cry ‘foul!’ consider how the great majority of modern-day rebels (sigh) hanker after lookalike Harley-Davidsons as part of their uniform, and if they cannot afford or indeed tolerate the Real Thing, they go off and buy Japanese copies of the H-D instead), and bikes which look like no other always have a hard time in the showroom.

After sacking the unfortunate Mr Poppe for doing exactly what his design brief called for, BSA’s own design and engineering chaps set to work to give their Sunbeam S7 a facelift, in the hope that a little more commercial success could be garnered as a result. As the S7 was a wholly new design, sharing almost no components with the more mundane models in the BSA catalogue, its tooling investment would have been considerable. BSA could not afford to simply kill it off after a few years of marketplace lethargy. And so, after adding both lightness and a little less eccentricity of appearance, the Sunbeam S8 appeared.

The changes wrought by BSA engineers to the original S7 included shaving 35lb from its weight, fitting more conventional tyres sizes (3.25 x 19 front and 4.00 x 18 rear), adopting the more conventional BSA/Ariel front fork and adding the appropriate BSA front anchor. For some reason, the new, lighter-look model gained a new tubby-look silencer, cast in handsome aluminium. Baffling, we might say, punnily. Whatever, the S8 silencer certainly sounds better than that on the S7.

And the S8 rides better too. Out on the rural roads of Shropshire most glorious and Cheshire the more affluent, the S8 seen in our smudgy pics proved to be an absolute treasure. OK, so it’s fitted with a slightly oddly converted headlight (although the shell is correct), and the black finish is hardly as impressive as the fine gunmetal version offered as an alternative, but neither of these details detracted from the bike’s rideability. It must be said that I always feel right at home on Sunbeam twins. Maybe they were intended for tubby middle-aged blokes?

The ground clearance is still lamentable, the brakes are still in little danger of rippling the tarmac, and the rider still bounds about on the single saddle while the rear suspension appears not to move at all (despite the wear marks on the plunger shrouds), but the Sunbeam is always a very pleasant motorcycle to ride. So long as you’re not in a hurry, of course. And if you are in a hurry, then buy a Norton.

The heart of the bike’s charm is its engine. Mr Poppe’s in-line twin spins along a treat. There’s some vibration, but the rubber mounting takes any stress away from the rider, and if there really are a few more horses than in the S7 lurking with the S8… well, they are surely relaxed, reliable horses, rather than high-spirited snorters!

Starting is always easy, tickover is ready and reliable, the clutch is light, bites predictably and without fuss even in heavy, slow traffic. The four gears are perfectly spaced for the available performance, allowing top to be selected well before 30mph, and once engaged only the steepest of inclines or the need to stop demands a downshift. Overtaking at speeds over 35mph is as easy (or as difficult!) in top gear as it is in third, so plan ahead and relax your riding style; downshifting will not increase your acceleration much. The same comments apply well to the S8’s anchors, too, and forward planning is a good idea if you are intent upon entering the racy world of an A-road.

Starting is always easy, tickover is ready and reliable, the clutch is light, bites predictably and without fuss even in heavy, slow traffic. The four gears are perfectly spaced for the available performance, allowing top to be selected well before 30mph, and once engaged only the steepest of inclines or the need to stop demands a downshift. Overtaking at speeds over 35mph is as easy (or as difficult!) in top gear as it is in third, so plan ahead and relax your riding style; downshifting will not increase your acceleration much. The same comments apply well to the S8’s anchors, too, and forward planning is a good idea if you are intent upon entering the racy world of an A-road.

It is perfectly possible to cruise the S8 at an indicated sixty, but if you need to do this a lot you are missing the point of the model and are likely to become as stressed as the engine will sound. No, sound advice would be that S8 riders should take to the more minor roads, roads of which there is an abundance in the more country counties of the land, for that is where the gentleman’s motorcycle is most at home. This would be a most fine machine for passing one of those balmy, blue afternoons of which we’ve been seeing a lot this year.

But the big question: S7 or S8?

It depends upon what you want. If the purity of the original concept is more important to you than the effectiveness of the riding machine, then buy an S7. The S8’s redesign is a compromise demanded by the original model’s market failure. If you want the better bike, and if it must be a Sunbeam (for that unique charm, maybe) then buy the latest S8 you can find, preferably one fitted with the mods developed by Stewart Engineering over the years.

And then take the old gent out for a spin whenever you can. The Sunbeam has a charm which grows on riders with use; familiarity breeds content, not the other thing…

Classic and British bikes like this one appear every month in the pages of RealClassic magazine. Our in-depth articles by expert and enthusiast authors reflect the old bikes we buy and ride in the real world: frequently fabulous; occasionally awful, but always interesting…