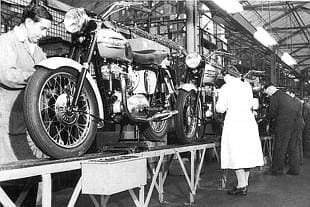

It’s a big event when you reach the ripe old age of 65, another chapter in your life comes to a close and thoughts start to turn towards your mortality. The other day, I was standing at my workbench, putting together a 1961 TR6 ‘Trophy’ engine, when my mind went back to 1961, to my time on Production Road Test, at Meriden. It was possible that I had actually road-tested the machine, fitted with this very engine. Thinking about that time of my life and the other 11 testers, it all came flooding back.

Four of the testers favoured the smaller capacity models such as the Cub, Twenty-One, 5TA and T100A, with the rest of us concentrating on the larger 650cc models.

So, there was a one in eight chance I’d ridden the bike with this engine when it came off the track all those years ago.

It’s been nearly 50 years now that I’ve been associated, in one way or another, with Meriden machines and there’s never been a day go by that I don’t think of my old pals, some gone now. Most of them were older than me, because I was only a lad when I started there. The chaps from whom I learned and to whom I looked up were perhaps in their late twenties, or even in their thirties or forties, but through my young eyes were middle-aged men.

Meriden’s Experimental Department was my first placement, after demob’, working with Percy Tait, ‘Pop’ Tilley, Dennis Austin and Alan Gillingham, great blokes who really knew their stuff.

Meriden’s Experimental Department was my first placement, after demob’, working with Percy Tait, ‘Pop’ Tilley, Dennis Austin and Alan Gillingham, great blokes who really knew their stuff.

Alan prepared the 1959 Tiger 110, converted to Bonneville spec, upon which Percy hurtled up and down the M1 every day, at a rapid rate. The TR6 engine on my bench looks much the same and that, coupled with Percy’s name, reminds of one sunny day, when we sat down for our sandwiches, looking out over the factory front lawn and the Coventry to Birmingham road. Percy was due, or he’d miss the first canteen sitting and be late for his second run. Then we heard the ‘monster’, as the hot prototype was called, approaching on full song. Swift down-changes, then Percy rode straight through the open doors, just missing us, screeched to a halt, flopped the bike on to its side stand, ran across the workshop to the steps down to the toilets and virtually dived down them headfirst. We all just sat open mouthed, until the huge form of a traffic policeman almost filled the open door.

Behind I saw the Sunbeam Talbot 90, with its chrome bell above the front bumper and blue police sign in the grille, parked on the drive. The chap was at least six three and with his flat cap, belted jacket, jodhpurs and gleaming black boots, stood there, feet apart and fists clenched. He surveyed us with a jaundiced eye. “Has a chap come in here riding a bike?” We all looked blank and shook our heads as one, “No officer” we lied through our sandwiches. He stared at us, then at the ‘Monster’, tinkling as it cooled. “Well,” he said, “you tell that bloke who hasn’t just come in here, I’ll have ‘im, oh I’ll have ‘im, don’t you worry.” With that, he turned abruptly on his heel, walked out, got into the Sunbeam drove away.

Alan shouted, “OK ‘Sam’ (Percy’s nickname), he’s gone, you can come out now.” Percy went off for his canteen lunch, whilst Alan and I checked the bike over for his second run. They did get him a few days later, and it was the same ‘copper’ but that’s another story.

Production Testing was a good time, and my best friend was Bill Letts, a giant of a man who originated from Cubbington Village, near Leamington Spa. He was always laughing, and loved watching Daffy Duck and other Disney cartoons. One of his great loves was food, especially a freshly baked loaf and a lump of cheddar. Often we’d sit in Somers Lane, half way down the Meriden Mile on the test route, in the summer, with our bread and cheese, discussing life in general — what a way to earn a living! When I first went on to Production Test, the older testers like Bill Langly would have nothing to do with me. I’d just come out of the Army, the ‘White Helmets’ (Royal Corps of Signals Motorcycle Display Team), and I guess they thought I was a know-all young ‘un. Eventually Bill got to speaking and soon put me right on the do’s and don’ts of the test run. This was the start of a friendship that has lasted right up to his passing last year.

It was Bill that introduc ed me to the noble art of toxophily, or archery as most people know it. At lunch time, we would discuss the latest bows from America, where archery was a really serious sport. Bill brought in his latest bow, a powerful ‘Black Mamba’ recurve bow, made of various layers of fibreglass and laminated wood.

ed me to the noble art of toxophily, or archery as most people know it. At lunch time, we would discuss the latest bows from America, where archery was a really serious sport. Bill brought in his latest bow, a powerful ‘Black Mamba’ recurve bow, made of various layers of fibreglass and laminated wood.

He barged through the rubber swing doors, riding an American West Coast ‘Thunderbird’ in the new pastel colours and high-rise bars. Slung across his back was his bow bag, containing his new unstrung bow and six dural’ arrows. He shouldn’t really have brought a dangerous weapon into the workplace — in today’s violent society, we’d have the Police Armed Response Unit over us like a rash — but this was 1961, and everything was much more sensible.

We crowded around at lunchtime, as Bill strung the bow and we watched in awe as he pointed out the main points of the bow and explained its performance.

On the other side of the main gang-way, which ran from the offices, down to the rubber swing door exit, was the Packing Department. About 30 yards away, were rolls of corrugated cardboard, about five feet in diameter, stacked to the roof. He picked up an arrow and, in one smooth movement, drew back the bowstring to his right cheek, then let fly. He repeated it another five times, putting the arrows into the uppermost roll. All six could have been covered by a pocket handkerchief. We’d never seen anything like it and I was hooked immediately.

Unfortunately Bill’s exhibition did not meet the finishing shop foreman’s approval, who went mad when he saw the six arrows protruding from the cardboard. Nothing came of it however. It was a while before that particular roll was used, but the six neat holes were there every morning to greet us.

As I write this, the we ather is beautiful. The Hinckley Triumph factory goes from strength to strength, particularly since the devastating fire last year. Their new Triumph has just won the 600 TT, but I’m reminded of my old chum from Shipley, Tony Jefferies and the tragic loss of his lad David. My memories, of course, go back further than Tony and when he was working with me in the Service Department during the Sixties, indeed back to the time when his father Alan was in his prime. He was a talented man, so you can understand why Tony and his son David were so brilliant. Alan rode in the TT and was also captain of the Triumph works ISDT team, in 1948, with other greats like Bob Mauns, Jim Alves and Alec Scobie.

ather is beautiful. The Hinckley Triumph factory goes from strength to strength, particularly since the devastating fire last year. Their new Triumph has just won the 600 TT, but I’m reminded of my old chum from Shipley, Tony Jefferies and the tragic loss of his lad David. My memories, of course, go back further than Tony and when he was working with me in the Service Department during the Sixties, indeed back to the time when his father Alan was in his prime. He was a talented man, so you can understand why Tony and his son David were so brilliant. Alan rode in the TT and was also captain of the Triumph works ISDT team, in 1948, with other greats like Bob Mauns, Jim Alves and Alec Scobie.

Speaking of the Isle of Man, my memories are of another ‘great’, a big Irishman called Ernie Lyons.

My father, Triumph through and through, and who had actually owned the 1935 model, 5/5, ridden by Alan Jefferies in that year’s ISDT, related the story of the Irishman’s ride in the first event to be held on the mountain course since the end of the war. It’s been imprinted on my memory since 1946, when I was only nine years old. I can still see my father’s face as he recounted the race, the appalling conditions, dark, misty rain and fog. Dad went over and witnessed this howling apparition as it flashed by in the gloom. The other riders had eased off, but not Lyons — he went quicker still! How he could see where he was going was a mystery, but for many years after, when I was a Meriden in the Fifties and early Sixties, brave man paled when this awesome performance was spoken of. Dad was at Union Mills and reckoned you could hear the wail of the prototype ‘Grand Prix’ on full chat, long before you could see it then, in a flash was gone, with only the fading sound of the twin megaphones to let you know it was ever there!

This story, and the reason I thought so much of dear old Alec Scobie, was because he tested all the ‘Grand Prix’ models on the road and took them to their maximum velocity on the old A45 – pre speed cameras of course. Alex was my boss for a while, then when I started my own restoration business and had a stand at the International Classic Bike Show each year, Alec would join me and be in his clement, talking to old friends and answering technical questions. I still have all his test reports on the GPs he tested.

Standing at my workbench, day-dreaming of the service department and all its characters, gets me no further with the engine. I look at the spanner in my hand, and can remember exactly how long I’ve had it, when it was issued and by whom. One of the nice things about being a fitter at Meriden, was that when you were proficient, you were issued with a full and comprehensive tool kit. This was your responsibility, you maintained your own tools, replaced damaged items and above all, kept them in a toolbox and kept them clean. There were however, more sinister uses for them.

Standing at my workbench, day-dreaming of the service department and all its characters, gets me no further with the engine. I look at the spanner in my hand, and can remember exactly how long I’ve had it, when it was issued and by whom. One of the nice things about being a fitter at Meriden, was that when you were proficient, you were issued with a full and comprehensive tool kit. This was your responsibility, you maintained your own tools, replaced damaged items and above all, kept them in a toolbox and kept them clean. There were however, more sinister uses for them.

On odd occasions we’d use the spanners to play tricks on each other. In this instance, I was on the receiving end. The actual spanner I’m holding has painful memories, due to one of the older fitters having the ‘half crown’ joke played on him. It happened like this. A half crown piece was held by pliers, over the soldering pot Bunsen burner flame. When the intended had his back turned, the hot coin was gently placed on his workbench. As soon as he noticed it, there would be a furtive look around, before he reached for the coin, concealing it within his closed hand. There’d be a count of three, before the shriek, followed by hilarity all down the line. He saw me laughing, and being the youngest, I should have kept my wits about me – but I didn’t.

This particular spanner is a good flat ring, part number D360, part of the toolkit supplied with a new bike, but as its such a useful little tool, all the fitters had a few for their own use. It’s ideal for cylinder base nuts on the 350/500 unit twins, and the Mag’ securing nuts on pre-unit 500/650s.

I was tightening the base nuts on a 1964 Tiger 100 SS when 1 received a call of nature. Whoever it was acted quickly, heating the spanner before returning it exactly where it was, so that I suspected nothing. I swear I picked it up and tightened another nut before the pain set in, a second before throwing it to the floor, accompanied by a chorus of laughter. With a rueful look around, I saw grinning faces — the biter had been well and truly bit!

I was tightening the base nuts on a 1964 Tiger 100 SS when 1 received a call of nature. Whoever it was acted quickly, heating the spanner before returning it exactly where it was, so that I suspected nothing. I swear I picked it up and tightened another nut before the pain set in, a second before throwing it to the floor, accompanied by a chorus of laughter. With a rueful look around, I saw grinning faces — the biter had been well and truly bit!

My father, being a carpenter, made me a magnificent toolbox, with detachable trays for the smaller tools, and a main compartment for the larger ones. The interior was stained and varnished, the outside and hinged lid, painted in gloss black enamel.

There was a brass mortice lock for the lid and a pair of beautiful chrome hinged handles, one for each end. I later discovered that the chrome handles were from the Rover car company, at Solihull, and that they were actually internal door handles from the cars.

That toolbox, just as Dad made, rests by my side, along the bench today. A feeling pride, mixed with comfort and satisfaction, to know that something my father made for me nearly half a century ago, containing the special tools I was issued with at Meriden, is still being used almost every day. This still isn’t getting the engine finished but again my thoughts turn to my tester friends, there are a few of us left, and it’s said that the older we get, the dafter we get.

Triumph centenary

Last year was the Triumph centenary, with a big gathering scheduled to meet at Meriden, on a Sunday morning, and a parade with hundreds of Triumphs, new and old, to the centre of Coventry, at the new Canal Basin, site of the old Dale St. Works. It was a beautiful morning, with riders from literally all over the world taking part. It was truly amazing that there were so many Triumphs, all at the same place at the same time. Some weeks earlier, the Triumph Owners Club of Great Britain had asked me, as a Vice President, if I’d like to lead the parade on my 1952 Tiger 100, JRW 405. Obviously I was honoured, but felt that as other ex-Meriden men were still around, some of them ex-road testers like me, and still with their own bikes, should be in on the act too. The organisers thought it as good idea so we gathered some together. There was Jim Lee, ex Production Development Tester, on his new Bonneville Centennial, Colin Smith on his trick Tiger Cub trials model, yours truly on JRW 405 and Eddie Dent. For those of you who have read my book Tales of Triumph, Eddie is the joker. As a tester, with me, he was irrepressible, always laughing and always up to something. Picture the scene, a huge gathering of Triumphs, all fired up and waiting to move off, when Eddie arrives, laughing, on a blue Kawasaki twin!

As I stand here at my work bench I count myself lucky to have friends as good as these. Smithy, on his Trials Cub, left his position in the parade and rode up to the front, to me. He had joined the Royal Signals Display Team as I had left, to take my place as Rider/Team Fitter. We had known each other since 1954 — we looked at each other, and rode along, him with his right arm around my shoulders, and me with my left arm around his. Friendship is a wonderful thing when it lasts this length of time.

Smithy takes me to my final recollections of comradeship, where Triumph workmates, Army companions and Triumph motorcycles all merge. We were called up together to do our National Service, as were others from Meriden, but they weren’t lucky enough to be able to get into the prestigious ‘White Helmets’. Several other of my friends, through being members of ‘the team’, when de-mobilised, found jobs at Meriden, such as Alistair ‘Jock’ Copeland, a super road-racer who did well both in the TT and the Bol d’Or, and perhaps the two most well known Meriden men, Percy Tait and Les Williams, both of ‘Slippery Sam’ fame. Alt of us will, by the time you read this, have enjoyed a display team reunion, up in the Garrison town in North Yorkshire, in September — what a ‘do’ that will be. My point being, friendships that were forged almost half a century ago, both at Meriden and in the Army, are so strong today, that only the man upstairs’ can end them. Yes, Triumph has been good to me, for all my working life, and my couple of years in the Army, very, very good, but I must finish this engine!

Smithy takes me to my final recollections of comradeship, where Triumph workmates, Army companions and Triumph motorcycles all merge. We were called up together to do our National Service, as were others from Meriden, but they weren’t lucky enough to be able to get into the prestigious ‘White Helmets’. Several other of my friends, through being members of ‘the team’, when de-mobilised, found jobs at Meriden, such as Alistair ‘Jock’ Copeland, a super road-racer who did well both in the TT and the Bol d’Or, and perhaps the two most well known Meriden men, Percy Tait and Les Williams, both of ‘Slippery Sam’ fame. Alt of us will, by the time you read this, have enjoyed a display team reunion, up in the Garrison town in North Yorkshire, in September — what a ‘do’ that will be. My point being, friendships that were forged almost half a century ago, both at Meriden and in the Army, are so strong today, that only the man upstairs’ can end them. Yes, Triumph has been good to me, for all my working life, and my couple of years in the Army, very, very good, but I must finish this engine! View original article