Ian Munro is a lifelong motorcyclist whose taste for the unusual even shows in his favoured flat twins, where rarities like a Ratier (TCM February 2003) have featured alongside the expected BMWs. During the years his machines have varied much more widely than that, though, starting with a Trojan motor attachment for his bicycle. “It was all I could afford when I was taking my law finals,” he says, “but since then I’ve had dozens of bikes ranging from a Triumph Terrier to a Royal Enfield Constellation. I even had a spell with scooters, and quite liked the Vespa (he’ll thank me for reporting that) but the Ariel Square Four is one machine that’s stayed in my garage for a long, long, time.”

But to regard an Ariel Square Four as a single entity is a bit like mentioning a BSA Bantam and expecting your listeners to know which of the many models you are talking about. In fact, it’s even more open to misinterpretation than that, as the Banty only evolved from an affordable commuter into an affordable learner’s bike. The big Ariel, on the other hand, totally reversed its character during its nearly 30 years of production. Starting life as a lithe sportster in an era when big sidecar machines were commonplace, it finished up as one of those self-same heavyweight sidecar tugs in a period when fast solos had become the norm. To make the transmogrification even more extreme, its capacity was doubled along the way – making it by far the biggest home market motorcycle – and its sporty overhead cam valve operation had been replaced by conventional pushrods.

I don’t know how happy the Square Four’s initiator, Edward Turner, was about all this, but I suspect he didn’t care too much. The model had served the purpose of getting him into the manufacturing side of the industry, and when Ariel took over Triumph, he’d moved between factories to become even better known as the man behind the Tiger singles and the trend-setting Speed Twin. Long before the demise of the Square Four he had become Supremo of the conglomerate, and had much more pressing concerns than the fate of an expensive and poorly selling model.

But while the Squariel was never a big seller, they were all ‘head turners’ (if you’ll pardon the pun) on account of an engine layout that was totally original yet completely logical. Small wonder that the Square Four demanded such attention, and was soon awarded the accolade of a nickname. Even the publicity-hungry Edward Turner may not have foreseen that happening, but he must have been delighted when journalist Dennis May (writing in Motor Cycling magazine under the nom de plume of Cyclops) contracted the clumsy ‘Square Four Ariel’ title into the apt and catchy moniker of ‘Squariel’.

But while the Squariel was never a big seller, they were all ‘head turners’ (if you’ll pardon the pun) on account of an engine layout that was totally original yet completely logical. Small wonder that the Square Four demanded such attention, and was soon awarded the accolade of a nickname. Even the publicity-hungry Edward Turner may not have foreseen that happening, but he must have been delighted when journalist Dennis May (writing in Motor Cycling magazine under the nom de plume of Cyclops) contracted the clumsy ‘Square Four Ariel’ title into the apt and catchy moniker of ‘Squariel’.

That first model – the 4F31 – was announced in November 1930. Like all the later Squariels it was effectively a pair of parallel twins with their crankshafts geared together, but it had a chain driven overhead camshaft and a capacity of only 498cc. Despite this, it earned early publicity – and foreshadowed its future career – by winning a ‘Gold’ in the 1931 London to Land’s End Trial with a sidecar attached.

Already there were demands for more oomph and less buzz, and Ariel responded with commendable speed by introducing the 1932 601cc Model 4F6.32. This had slightly oversquare dimensions in a new cylinder block, and both models received improvements to cooling and head sealing in response to criticisms that would dog the Squariel throughout its life. That the problems may have been overstated was shown by successful participation in the 1932 Maudes Trophy attempt, when one of the bigger versions covered more than 700 miles in under 700 minutes at Brooklands, and achieved a final flying lap at 87mph.

The Squariel survived the 1932 bankruptcy of Ariel’s parent company – Components Ltd – but by 1933 the smaller model was only available to special order. There presumably weren’t very many of these – especially as that variant was actually more expensive than it bigger brother – and by 1934 only the 4F6 was in production. The difficult times were indicated by the way Ariel now dropped the suffix numbers that indicated the year of manufacture; dealers had a hard enough job selling the current year’s production, but trying to shift a 4F6.33 in 1934 would have been nigh impossible!

Improvements continued though, with the machine being made lighter and more compact, and the cylinder block and head holding arrangements were revised yet again. Interestingly, the Square Four also received the rubber-mounted handlebars that were introduced across the range in 1934, although few machines can have needed them less. Much publicity was gained by the Bickell brothers’ attempts to be the first to cover 100mph in one hour on a 500cc British machine at Brooklands, but repeated failures to keep the cylinder head and block united reinforced potential customers’ concerns, and probably did the Squariel’s reputation more harm than good.

Redesigned Square Four

Perhaps to get rid of the ‘fast but fragile’ image, Edward Turner did a rare volte-face in 1936, and announced a completely redesigned Square Four simply designated the 4G. Making it much more suitable for sidecar duties, it now had real grunt with a nominal capacity of one litre, and full car-type crankshafts replaced the previous overhung cranks to give more of the flywheel effect needed for chair lugging. Most significantly, a camshaft located in the centre of the crankcase replaced the overhead camshaft, so the Squariel could no longer be promoted as a high-revving sportster.

Could it be that Turner had lost interest and faith in his original concept, or was he already practising the ideas that would result in the influential Speed Twin a couple of years later? Whatever, he departed for Triumph, and behind him he left a Square Four having only its cylinder arrangement and a high price tag (25 per cent more than the next model in the range, the much racier VH Red Hunter) in common with its predecessors. Even if it was intended for the sidecar brigade, though, the 4G was still a potent machine, with two and a half times the power of the other specialised tug in the marque line-up – the 600cc 15bhp sidevalve single VB.

And that preamble leads me onto the test machine, because it’s one of the first examples of the new breed, and it’s in remarkably original condition. “That’s because it had a sheltered one-family history until I bought it,” says Ian Munro, who lives on the south coast. Rather appropriate, that, because the Ariel has never been far from the sea. Most unusually, it was initially purchased by a tradesman in Malta, and I can’t think of many places less needful of one of the UK’s biggest and fastest motorcycles than the tiny Mediterranean island.

Developing nature

Developing nature

True to its developing nature, though, the Squariel was hitched to a sidecar as family transport, and in that mild climate it was doubtless preferable to the small saloon car that would have actually cost less. It was apparently used in that role for years, although civilian motoring was presumably practically non-existent on the beleaguered island during WWII. It would be fascinating if any of our readers could remember the Ariel in use during that period, as I’d guess that the outfit might well have been pressed into military duties, and played its part in earning the George Cross for the Island.

Be that as it may, the combination survived unscathed, and in due course passed to the original owner’s son, who carried on using it. He, in turn, eventually transferred it to his son who was evidently not a motorcyclist, because as far as Ian knows he never rode it. What he did do, though, was bring it with him when he left the island and moved to England. Ian was by now practising in the legal profession, and a business contact – knowing of his interest in old bikes – alerted him to the Ariel’s availability. Twenty-five years ago, Ian became only the fourth owner of the Squariel – which by now had been parted from its sidecar – and he has used and cared for it ever since.

Beautiful and unusual

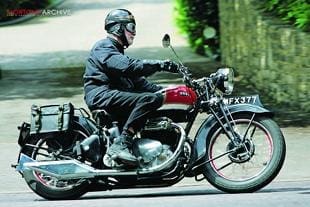

Regular readers will remember Ian’s nae as the restorer of some beautiful and unusual machines (the extraordinary flat twin IFA featured in TCM January 2004, for example) but he has wisely resisted the temptation to remove the Squariel’s fine patina of use. “Despite always having been kept near the sea,” he says, “the Ariel has survived very well. When I first bought it, I wasn’t really into restoration and I admit that I painted the tank black, but I’ve since stripped that and repainted it in the correct pattern. Otherwise I’ve only had the wheel rims re-chromed, and a local craftsman re-covered the saddle in leather.” This sympathetic work means that the 4G looks well-cared for rather than strikingly glitzy. But it has all the smart period embellishments that made post-vintage Ariels some of the most stylish bikes around – just look at that shapely front number plate and those extravagantly flared mudguards – and it has some features you wouldn’t really expect, like the prop stand that curiously operates on the right hand side.

Ian’s ownership hasn’t been entirely trouble-free, though. The wheels had to be rebuilt twice, because spokes started breaking, which was rather strange when the original ones had stood up to sidecar duties. But more frustratingly, his early years of ownership were plagued by ignition problems and partial seizures.

“The magneto used to cut out on the rear cylinders, even after I had it rebuilt,” he recalls, “and every time it slowed, or came to a halt, I could hear the pistons squeaking in the bores. Of course, people kept telling me that Square Fours do that because the rear cylinders run hot, but when I thought about it, I suspected that the two problems were interconnected. If the engine continues running with one or two cylinders dead, then obviously petrol is still being pumped through them, and it will wash the oil from their bores, causing the pistons to pick up. Eventually, I found an HT coil in a scrapyard, converted the bike to battery ignition, and since then I haven’t had a single problem.”

Sounds reasonable to me, especially when Ian demonstrates that his period-looking Delco coil produces a spark that easily bridges the one-inch gap between the distributor’s central pick up and the side contacts. Ariel presumably came to a similar conclusion, and by 1950 also relied on coils to provide the sparks. Whatever, Ian’s Squariel now starts as easily as it should (seven starts by seven schoolboys was part of the 1932 Maudes Trophy stunt) and it runs just fine. I can’t say that it feels like a super-sportster – it sits too stolidly on the ground for that – but it feels immensely stable and capable, and the brakes and handling are quite adequate for the sort of serene progress you are likely to make. Nobody with any mechanical sympathy would take a Squariel anywhere near its maximum speed these days, but even this 70-year-old one has a cruising speed of 60mph or thereabouts, and has lively enough acceleration to keep ahead of the traffic light Grands Prix.

Comfort would be no bar to achieving high mileages, either. The rear end has no suspension (the complicated Anstey link only became an option on later models) but the substantial weight means that the bike simply ploughs through most road hazards, while the saddle springs soak up the rest of the shock. Unlike many pre-war bikes the riding position is not at all cramped, and the engine layout (where all the moving components balance each other out) guarantees that there is virtually no vibration to challenge the rubber handlebar mounts.

Comfort would be no bar to achieving high mileages, either. The rear end has no suspension (the complicated Anstey link only became an option on later models) but the substantial weight means that the bike simply ploughs through most road hazards, while the saddle springs soak up the rest of the shock. Unlike many pre-war bikes the riding position is not at all cramped, and the engine layout (where all the moving components balance each other out) guarantees that there is virtually no vibration to challenge the rubber handlebar mounts.

By the early 1990s, Ian was pleased enough with his big Ariel that he took it back to its first home, participating in the Blue Label Rally organised by well-known Maltese enthusiast Joe Anastasi. He sent it – along with other entrants’ bikes – in a container, but I suspect that he could have done much of the trip overland with no problems, because a well-sorted Squariel gives the impression that you could set out on a marathon journey confident that its stamina would exceed your own. The first one-litre Square Four might be have been listed as the 4G, but with its Grand Turismo characteristics, and impressive appearance and specification, I’d add a ‘T’ to that designation.