The A7 is one of those bikes which never seems to get much attention, but everyone is comfortably familiar with the breed. It’s so similar to the A10, and was around for so long, that it’s no more remarkable than the saggy sofa in the corner of the spare room. However, if you’re yearning to experience a snapshot of old England, or if you want to know just why the parallel twin dominated our market for so long, then the A7 is a cracking candidate to take for a spin.

Just about everyone had a hand in the development of the A7. It was BSA’s big push into the land of the parallel twin and was originally scheduled to appear in the late 1930s, to sell to the market which so obviously adored Turner’s speeding twin. Val Page worked on the A7 design in the 1930s before moving back to Ariel, and then everything stopped for a spot of war, and so it was 1946 before Herbert Perkins (‘a first class engineer’ according to Bert Hopwood), oversaw the launch of the original A7. The first version was a 495cc, 26bhp, iron head twin with a single camshaft, pushrod-operated overhead valves and a single carb, housed in a duplex frame with rigid rear end and BSA’s tele forks.

The result was almost exactly what BSA had been aiming for; ‘a dependable workhorse for everyday use… a machine that could be serviced in a backyard with just a few basic tools,’ according to Owen Wright. The A7 looked like a proper BSA, it was priced like a proper BSA at £171.10s, and it went pretty well, too. The Motor Cycle squeezed 82mph out of their test bike in 1947, running on whatever passed for petrol in those days, and with the rider dressed for foul weather and riding in the yakking rain. The tester considered the A7 to be ‘an outstandingly attractive machine,’ and thought it was ‘assured of a brilliant future among discriminating riders – those who can evaluate genuine, worthwhile features.’

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

That prediction wasn’t too far off the mark. BSA gave their parallel twin a thorough overhaul for 1950 to tackle its teething troubles (most notably a ponderous, clunky gearchange), and it then romped on as the A10 and A7 for 12 more years, and kept going thereafter as the unit construction A65 and A50. In fact, BSA built so many parallel twins that I couldn’t add up all the production figures to impress you with the total number (but if anyone out there has that data I’d be delighted to hear of it…). A brilliant future, indeed!

Norton’s revolving door

Back in 1949, meanwhile, Bert Hopwood arrived at BSA after he’d taken a quick spin in Norton’s revolving door and before he joined AMC. Hopwood’s remit at Small Heath was, in his own words, to address ‘some major engineering problems which were bedevilling the Service Department repair shops and I clearly remember my very first task being a re-design of their major gearbox.’ Told you the gearchange was clunky…

The next job on Hopwood’s To-Do list was to spruce up the twin engine. ‘I was asked to re-design the 500cc twin engine to permit unimpeded air cooling and a more efficient combustion function.’ Oh, and while you’re at it, Bert, just knock out a whole new model would you? That’s just what he did, in about a month. ‘At the same time a 650cc version was designed which became the Golden Flash.’

The new A10 was brought to the market before the revamped A7, because that Turner bloke had launched his Thunderbird and BSA wanted their 650 on the streets, too. However, the rush to get the 650 into the shops inevitably meant that some corners were cut, and Hopwood winced at some of the short cuts they took – which inevitably had to be corrected in subsequent years.

With the 650 established, the new A7 was launched in 1951, and the re-designed 500 engine shared very few components with the previous model. However, the A10 and A7 were extremely similar under the skin, with 90% or more of their parts being interchangable. The new A7 engine had a shorter stroke than its predecessor; reduced by nearly 10mm from 82mm to 72.6mm, which gave a slightly different capacity of 497cc and a slightly more lively feel to the motor. There wasn’t a great deal of difference in the ultimate power produced by the new A7 compared to the old ’un, up 2bhp to 28bhp, but it would rev a little higher and with a little more vigour.

The new A7 could also be tuned – or indeed, taken to competition in near-stock trim and with some success. Three A7s chosen at random from dealers in 1952 won the Maudes Trophy, which included a 4500 mile trek across Europe and the ISDT. Then a tuned but unfaired A7 clocked 123.69mph at Bonneville Salt Flats, and yet another A7 went on to win the 200 mile race at Daytona Beach in 1954. (And another A7 took second place in that race, too). Not bad for ‘a dependable workhorse’, huh?

In fact, Hopwood so liked his A7 engine that he wanted to replace the aging C11 with a 250 single that was essentially half-a-500, based on the twin. ‘The twins were modern and trouble free’ he thought, and ‘the new 250 looked smart, had a superlative performance and was extremely quiet in operation.’

In tests it lapped Montlhéry at nigh-on 100mph for three days on the trot and completed 30,000 miles with barely a blink. The BSA board were horrified at the idea of replacing a model which wasn’t completely and utterly out-dated, so the A3½ never went into production. Hopwood must have been looking for a softer wall against which to bang his head for a while!

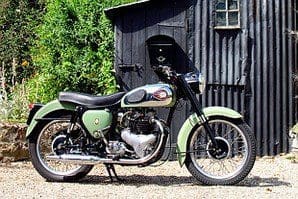

Back with the plot, the A7 evolved throughout the 1950s into the tidy motorcycle you see on this page. We rode a 1961 bike, nearly the last of the pre-unit 500s, which when new would have had its swinging arm rear end supported by Silentbloc bushes and Girling dampers. You’ll probably be familiar with the more glamorous Shooting Star variant – the sports 500 with high-compression pistons and alloy cylinder head – but this one is the cooking version, the A7 for everyday use.

I like 500 twins, me. I ride a Triumph 500 twin instead of a 650 or an over-stressed 750, and I wanted to see what BSA’s 500 twin was like…

Lacked the zing

Well. It ain’t nothing like the Triumph and that’s for sure. Steve Wilson once said that the A7 ‘may have lacked the zing of a Triumph but its prospects of holding together were infinitely better’ and after my morning’s ride I don’t doubt a word of it. The A7 started very easily, second kick from stone cold, and quietened down to a murmur at a steady tickover. It had been stood for quite a while – refurbished but not much used – so the whole plot was rather awkward and inflexible at first. It felt like a stiffened muscle does the day after a long walk… like it needed a good stretch and maybe several cups of coffee before trying anything strenuous. Gently does it then – to start with, any way!

The sound of the BSA is entirely different to the Triumph 500. My T100 rattles and chatters and rasps like a good ’un. None of that from the Beesa. The A7’s top end purred, there was a gruff rumble coming from below and a pleasant ba-da-boom from behind. You could sneak out on this bike at 6am and be entirely unafraid of awakening the neighbours.

Mind you, the T100 reacts to a twist on the grip like the scalded cat that it is – while the A7 didn’t seem to possess anything which could be described as outright acceleration. I opened the throttle and after a while we gathered some speed. Nothing dramatic and, it has to be said, nothing to get the heart racing, but all the same we achieved a respectable pace in a few hundred yards with fuss-free grace. This is, after all, the bike which Motor Cycling described as ‘essentially sturdy, straightforward’ and ‘without frills’.

The clutch was beautiful and light – the gearchange noticeably notchy. I suspect the cogs would swap rather more freely after 500 or a thousand miles, but during my ride changing down through the 4-speed box needed to be a considered process and I didn’t manage to find neutral at any junction or appropriate moment. (Found it when aiming for second gear, though. Huff).

The riding position was really comfortable and more tilted forward than I expected; more sporty than the A7’s staid image suggests. I wasn’t sitting back, but leaning into the wind which made it easy to fling into corners. The forks and rear dampers were very stiff which made the ride pretty bouncy and unforgiving when, on an A7 of this era, it should have been supple and ultra-smooth. Still, the 500 held its line beautifully and there was plenty of flexibility once the engine was spinning at 3000rpm to motor confidently out of each bend as if we had an appointment to keep with the next one. Back in the 1950s, the testers would push on in third gear up to nearly 85mph – 50 years later, I wasn’t going to take it much further than 45 before shifting into top.

I’d heard that the A7 should be super-smooth but this one had a distinctly rough patch at around 50mph in top. It evened out again above that speed and the bike fell into a steady, comfortable long stride which we could’ve kept up all day – in fact, I did stay out on the A7 rather longer than planned so when I got back I was met by two worried-looking fellas who’s assumed I’d either run out of petrol or broken the thing. Not this time…

Mind you, I did manage to stop the engine inadvertently by fiddling with the red switch on the handlebars. When you ride unfamiliar bikes you tend to wiggle or press everything, just to see what it does. That particular button stopped the engine – and hence the bike!

Indeed, the kill switch did a far better job of slowing the A7 than its brakes. The rear 7-inch drum was OK – and nothing better than OK – while the similar stopper at the front was far less than OK. I’m used to marginal front brakes because my Dragonfly treats emergency stops as if they are a suggestion rather than an imperative, but the lack of braking on the A7 had me worried. It knocked 10mph off my standard travelling speed so I found myself doing around 45mph, and then I kept bumping into the vibration band which was frustrating.

So I asked Pat and Mike at Lyford Classic Services whether they had any clever fixes for BSA brakes from this era. But of course… ‘Over the years the brake lining material has changed for the better. Anybody who has old glazed hard linings – which we come across regularly – should replace them with new ones. Likewise, the drum wears oval and could need reskimming to make for smoother and more efficient braking. New cables will make hell of a difference, too!

‘On the ’58 onwards bikes, the ones that use the cast-iron hub, a good upgrade is to fit the A10 8-inch front hub rather than the 7-inch fitted on the standard A7.’

Thanks, folks. Any other suggestions for improving the A7?

‘Mike always junks the 6-spring clutches on the swinging arm models’ says Pat. ‘This is because the pattern parts for them, other than the clutch plates, are rubbish and you can’t set them up properly. So this makes neutral difficult to engage and causes the clutch to drag. We always use and recommend 4-spring clutches, especially now that we have overcome the clutch hub and pressure plate problems by having some made to our own specification. This makes the clutch a pleasure to use!

‘Another problem many A7/A10s have is weak front fork springs. Most people think that the springs they already have are fine, whereas they usually have softened over the years and a new set is required for a completely better ride. Then while assembling the forks, we have discovered that most people do not realise that they may require shims between the circlip and the top of the bush. This stops any “donking”!

‘Obviously, headrace cup and cones take a hammering over the course of time, and again 9 out of 10 times they need replacing. You should also check out the metallastic swinging arm bushes. Although these are very long lasting, they may have become soft and give a wallowing ride on the back.

‘Other than that – the A7s are great bikes…’

Pat may be slightly biased, seeing as Lyford specialise in pre-unit BSAs, but she’s not the only one to say as much. If you ask around, you’ll find that most people who have direct experience of the A7 share similar opinions. Back when it was new, the A7 was overshadowed by both its butch 650 sibling and the tricksy Triumph twins – those bikes could pull a family of four in comfort, or give a fast lad a quick getaway. But these days if you want to go fast you can buy a Suzuki… and so the A7 has come into its own. Or as the BSAOC say; ‘these machines were not the most sprightly or attractive of the vertical twins but it was certainly the most hard wearing , oil tight and quietest, running with a minimum of whine or clatter.’

Properly set up and run in, the A7 comes close to capturing the essence of traditional British motorcycling, and it does so at two-thirds of the cost of a posh 650 twin. Check out a few adverts and you’ll find A7s and the occasional A50 selling for much the same money as a 350 Triumph or even some 500 singles. Yet owning an A7 doesn’t make you a second class citizen. Our own Steve Wilson speaks very highly of them: ‘for me the A7/A10 twins are the definitive British motor cycle of this period, and possibly of all time. Perhaps Edward Turner got it right from the start, and 500cc is actually the optimum capacity for a parallel twin.’

So was I tempted to swap my 500 Triumph for the A7? Ah. No. Not this one. But I like my bikes to be a bit quirky and a bit querulous. I think the A7 might just have been too darned nice for me!

Classic and British bikes like this one appear every month in the pages of RealClassic magazine. Our in-depth articles by expert and enthusiast authors reflect the old bikes we buy and ride in the real world: frequently fabulous; occasionally awful, but always interesting…