Poor old Suzuki. It’s not often that a bike that is technically advanced and a good performer gets sidelined very quickly, especially after it’s had a very positive reception from the press. However, it happened to the Suzuki GSX550.

Back in the early 1980s, things were just starting to move in the sports 550 market. As a class, 550s had been around for nearly a decade. Suzuki had had its GT550 two stroke triple and Honda the popular CB550. Suzuki had then produced the GS550, which aced the Honda in just about every department and became almost the definitive Universal Japanese Motorcycle (UJM). Then in 1979 Kawasaki had surprised everyone by launching the neat little Z500 four, which swiftly metamorphosed into the Z550 and sprouted a sports off-shoot, the GPz550. Clearly high performance sports 550s were going to be the coming thing.

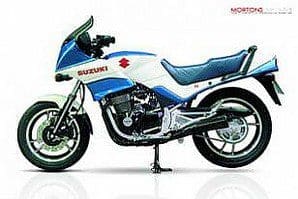

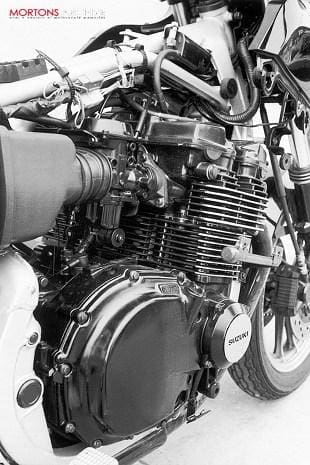

In 1983 Suzuki launched the all-new GSX series. The 550 as a completely new design. Gone was the old two valve engine: instead, four valve heads were fitted to an all-new plain bearing engine (the old GS series used a roller bearing crankshaft). Everything was lighter.

In 1983 Suzuki launched the all-new GSX series. The 550 as a completely new design. Gone was the old two valve engine: instead, four valve heads were fitted to an all-new plain bearing engine (the old GS series used a roller bearing crankshaft). Everything was lighter.

The old GS was, if truth be told, a bit of a porker. The new GSX’s engine was 7kg lighter. Suzuki lost another 1.5kg from the exhaust system and the same from the carburettors and airbox (the carbs were actually a pair of twin-choke Mikunis, rather than the normal bank of four single-choke units). And the frame was lighter as well. All in all, the new GSX550 weighed in at 198kg instead of 215kg, which was what the old GS missed.

And, oh yes, the frame. This wowed observers because it was made out of square section tubing. It looked like alloy but it wasn’t – it was good old-fashioned steel painted to look like alloy and people felt a bit let down when they removed the tank and panels and discovered that where you couldn’t see it, the frame used round steel tubing just like… well, just like an old GS550. But hell, it looked good.

It also had Suzuki’s new rising-rate monoshock rear end, dubbed ‘Full Floater’. Anti-dive units were fitted to the front forks along with new opposed-piston brake calipers. Things didn’t get much flashier in 1983.

The whole thing came with a good frame-mounted half fairing, painted in blue and white, with dashes of red here and there to mimic Suzuki’s race bikes. In fact, if you think about it, sporty Suzukis still come in blue and white with dashes of red…

The whole thing came with a good frame-mounted half fairing, painted in blue and white, with dashes of red here and there to mimic Suzuki’s race bikes. In fact, if you think about it, sporty Suzukis still come in blue and white with dashes of red…

So everyone loved it, right? Um, nearly. The engine was a delight: it was very smooth, despite an absence of rubber mounts or balancer shafts, and it possessed a very good spread of torque – much better than the peakier Kawasaki GPz for example. Possibly this was because it was a bit bigger than other 550s – it was actually a 572.

It stopped like the rest of the world had suddenly seized up. The suspension gave a quite astonishing ride for the time – it was plush and compliant and the first time I rode one I found myself going over bumps just to feel the suspension doing its stuff properly, which was a novelty back then, I can tell you.

And this was despite an absence of damping adjustment on the back. A remote spring pre-load was all you got. The front forks had two-position adjustable spring pre-load as well.

The real problem was with the handling. The frame was okay but the front end had the ‘Bright Idea of The Moment’ – the 16” front wheel. And the handlebars were quite high and wide. These gave excellent control and the fairing took care of the windblast problem, but the combination of supermarket trolley wheel and not much weight over it gave an unsettling lightness to the front end. If you hit a bump while cranked over, the front wheel shimmied this way and that before snapping back on course. Not dangerous, but off-putting. And it wasn’t a problem shared by the Kawasaki GPz, for example.

Furthermore, if you applied the brakes in mid-bend the Suzuki had an initially frightening tendency to sit straight up and try and go in a straight line. It was something you adjusted to and soon compensated for by forcing the thing down more into the bend and, to be fair, it wasn’t a problem unique to the GSX550 – but it was a bit unnerving.

applied the brakes in mid-bend the Suzuki had an initially frightening tendency to sit straight up and try and go in a straight line. It was something you adjusted to and soon compensated for by forcing the thing down more into the bend and, to be fair, it wasn’t a problem unique to the GSX550 – but it was a bit unnerving.

The GSX scored on comfort, though. It had a great riding position, a protective fairing, a really excellent seat, and it was a doddle to ride.

A shame, then, that it wasn’t as fast as the opposition – which meant the Kawasaki GPz550. In 1983 Kawasaki released the third, and definitive, version of its GPz550: the ZX model with the frame-mounted fairing and even more power. Suzuki’s GSX550 was capable of maybe 115-120 mph: the new GPz550 was nearly ten mph faster. The Suzuki engine just felt a bit flat and reluctant to rev, and after 9000 rpm the power was cut off as if someone had fitted a rev limiter.

In hard figures, the Suzuki was only three or four bhp down on the Kawasaki (57 bhp at the real wheel instead of 60-plus), but it developed peak power at 8600 rpm while the Kawasaki maxed out at 10,000 rpm. So yes, the Suzuki had more torque, but just didn’t rev on like the GPz, which was odd considering the GPz was actually an old-fashioned two valve engine design.

The Kawasaki also handled better. It too had a slightly light front end, thanks to the handlebar arrangement, but an 18” front wheel made it less twitchy.

The Kawasaki also handled better. It too had a slightly light front end, thanks to the handlebar arrangement, but an 18” front wheel made it less twitchy.

The GPz550, as we know, cleaned up. It was far and away the best sports middleweight of the day, and led directly to the watercooled GPZ600R and today’s crop of sports 600s.

After a while, fingers began to be pointed at the GSX550. The problem was reliability, or the lack of. Now Suzuki have hardly ever built a duff four stroke and there were no complaints about the engine. It was the electrics that gave trouble: both the electronic ignition and the entire charging system. Whatever faults Kawasaki GPz550s had, they didn’t usually include self-destructing electrics. The GSX550 faded away.

Suzuki tried several different versions. After a year or two they introduced the EFE, which was the same bike but with lowers added to the fairing, and at the same time you could have the EE, which was nearly naked – a tiny fork mounted flyscreen was all you got. This was a budget move – bike prices were rising sharply in the mid-1980s and many manufacturers were producing stripped-down versions of bikes. The EE was all of £450 cheaper than the fully-faired EFE, back in March 1984.

Anyway, the GSX550 series was phased out in 1988 as the new oilcooled GSX600 came in to replace it.

What goes wrong You’ve heard it already – the charging system is the real villain. What happens is that the alternator fries: it just gets hot and gives up. Or the regulator/rectifier fails on its own, and then the battery gets fed with 20 volts or more instead of 13-odd, boils dry and melts.

You’ve heard it already – the charging system is the real villain. What happens is that the alternator fries: it just gets hot and gives up. Or the regulator/rectifier fails on its own, and then the battery gets fed with 20 volts or more instead of 13-odd, boils dry and melts.

In extreme, but by no means rare, cases, you lose the alternator, reg/rec and battery all in one hit, and that’s expensive.

People deduced that running with the headlight on all the time reduced the reg/rec failure rate, but it was only delaying the inevitable. Fortunately, a cure exists in the form of a Honda CB250N reg/rec which fits and works. If the alternator goes, you can have it rewound.

However, no Suzuki GSX550 should ever be bought until you’ve put a multimeter across the battery terminals and determined that the thing is charging.

Ignition failure is even pricier, because you can’t just adapt another component to do the job. For some reason this is associated with failure of the electronic rev counter. If that starts misbehaving, the ignition is on the way out. Never, ever buy a GSX550 with a duff rev counter. You’ll be unable to repair it unless you’re an electronics genius, and the sparks are about to disappear with it.

The anti-dive is the usual mushy mess. If it hasn’t been disconnected and blanked off, it should be. And a lack of grease nipples on the rear monoshock means that the whole thing simply corrodes and seizes, so check carefully.