Motorbicyclists are a strange breed. We pride ourselves on our individuality; yet we join clubs and wear club regalia. We pride ourselves on our independence; yet we grasp every opportunity to huddle together to discuss our woes. While celebrating our unique enthusiasm, passion, whatever, we somehow feel a need to gather together, wearing similar clothes and riding the most popular bikes. I’ve always found this puzzling, and in many ways it has defined my own riding history, certainly influencing my choice of motorcycle, and my choice of motorcycle club. I always loved the notion of the Association of Independent Motorcyclists, a gloriously oxymoronic club of which I was once an appropriately inactive member.

Why am I rattling on like this, and what has this got to do with an unusual Matchless twin? Two reasons. First, I am a statistics fanatic. Part of the day job involves endless analysis of the equally endless streams of figures which the publishing world dumps upon its managers, and when I was running an old bike rag I was always dismayed by the simple statistical truth that sticking a Triumph twin on the cover notched up sales increases (although eventually I learned how to manipulate this to promote my own favourite marques). Secondly, my personal need for independence ironically delayed my acquisition, ownership and thorough enjoyment of a truly excellent motorcycle.

Cast your mind back…

Cast your mind back…

…to the late 1960s, early 1970s, when I was cutting my riding teeth. I have no idea what you rode (but feel free to assault the message board and tell me), but all around me in those formative Somerset summers rode – or wanted to ride – Triumph twins. This meant that Triumph twins, particularly unit construction 650 twins, were easily the most expensive bikes around. BSA twins were OK, and there were a lot about, Nortons were semi-mythical, not only for the relatively new and therefore unattainable Commando, but also for the depressingly famous featherbed models, and then there were The Rest. The Rest, predominantly the AMC and Ariel ranges, were affordable by the penniless, and that certainly included me!

Which is of course why I rode AMC and Ariel for so long, and where my continuing passion for those slightly quirky, and certainly out-dated when new, motorcycles was born. But like most motorcyclists of my acquaintance, I also craved acceptance. I also pretended to far greater knowledge than I in fact possessed.

Picture this: late 1971, and a youthful, slender, dark-haired me is working in Scotland, and for the first time ever I have a few shillings to hand. I desperately need a motorcycle. The 1948 AJS 18 I cut my big-bike teeth on is in Somerset, not Ayrshire, which is not entirely helpful, and I need a motorcycle. I really need a motorcycle, because The Gurl has written me a letter in which she is ending it all, agreeing with her parents that the distance between us is just too great! I don’t think that they were referring to the physical distance between Somerset and Ayrshire; more the cultural spacing, but who knows?

Two bikes leapt from the pages of the local rag. There was a 1961 Matchless G12, rebuilt, for £80 (I think), and a 1966 Norton N15, described as a ‘scrambles special’ for £95. The word ‘special’ instantly put me off (I had far too much experience of the appalling bodgery which that word implies), but went to look at both bikes anyway. The Norton, its supposedly proud owner told me, was a great and very powerful scrambler, combining the best of AMC and the best of Norton – I didn’t understand at the time that they were all one and the same company. Hence this odd machine had a Norton engine (a 745cc Atlas, no less), Norton wheels and Norton forks. The rest was most of a Matchless bicycle. Proud Owner started it and I ride it down his farm track. And I rode it back. It was harsh and horrible.

The G12 Matchless, on the other hand, was very sweet, and I bought it immediately. That was a payday Thursday evening; on the Friday evening I rode it down to Taunton in Somerset. And I rode it back to Ayrshire on the Sunday. It was a great bike, and I am chuffed to have an almost identical AJS 31 in The Shed even now. Although that animal doesn’t actually run, of course…

I remembered the 750 Norton hybrid, though, although I could find almost no reference to it anywhere in mine or my friends’ bike mag collections. A month later, I rang the man about his hybrid; was it still for sale? It was, and we could talk more sensibly about the price…

The day I was intending to go ride it again, a package from a buddy arrived. It was a doggy copy of Motorcycle Mechanics containing a roadtest of just this animal. I was impressed. Impressed that is until I looked at the picture of what I imagine must have been some editorial clod’s idea of the typical hybrid pilot; a saddo wearing studded leather, with a sort of bizarre peaked leather hat complete with dangling chains perched above his stupid sneer. Even at a tender 18, I recognised a serious lack of charm when I saw it, and gave up all ideas of joining the leather-toting hybrid riders.

Move forward to 1974 or so. Once more I needed a motorcycle, and once more I fancied a Matchless. Bought a G11, a 600cc twin of remarkable cheapness (it is in fact true that it was hard to give loads of old bikes away until the classic bike was invented in 1978), and it came with almost all of another machine, an engine-less skeleton with Norton forks and wheels into which the G11’s vendor had intended to put the engine from the eccentrically-steering G11. He wanted to build a special, of course; another damn caff-racer. Sigh…

I passed the later rolling chassis onto another AJS & Matchless OC member for the same price I’d paid for the whole ensemble, so I had a free G11. These things were important then! But I never forgot those odd Matchless / Norton hybrids, and when I was Editor of The Jampot, the AMC’s magazine, I picked up a lot of references to the last of the AJS and Matchless lines, which were 350 and 500 singles, and 650 twins, all of which used AMC’s engines, and rare 750 twins, which used the Norton Atlas engine, and which had been available in AJS, Matchless and Norton forms, and in several trims. I expressed delight at my acquisition of a 1966 AJS 31 650 not a million miles from home, and wondered in print whether any of the rare 750s were about still.

Which is how I bought my first hybrid from a nice man in Chicago. Once it was back in the UK (in those far off days few folk were importing old Brits from the States, and the bikes were often in fine condition and very cheap!) a friend made me an offer I could not refuse and the hybrid went away again without my even firing it up!

Which is how I bought my first hybrid from a nice man in Chicago. Once it was back in the UK (in those far off days few folk were importing old Brits from the States, and the bikes were often in fine condition and very cheap!) a friend made me an offer I could not refuse and the hybrid went away again without my even firing it up!

Another hybrid followed. This one was a UK model, a touring version, and a runner! But before I could enjoy it at all, another friend made me that offer, and away it went. Was this a lack of moral fibre or what?

Then I acquired another one from Les Emery at Norvil. I was ensconced in The Shed in Shropshire by now, and had both room and facility to rebuild it. But once again, the self-employed’s nightmare income tax scenario arrived as it does, and another friend made me an offer I couldn’t refuse. So that was another falling-at-the-last scenario.

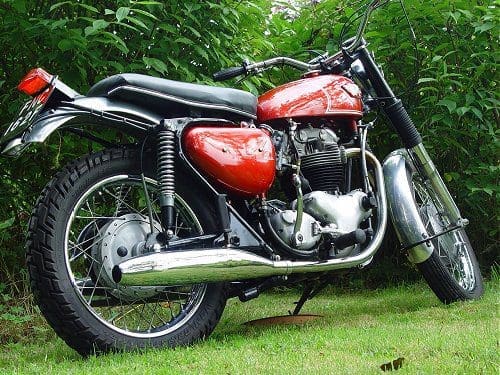

Finally, a couple of years ago – by which time I had ridden loads of 750 hybrids and had degenerated into a complete bore on the subject – yet another appeared before me; a 1967 Matchless G15CS, re-imported from the US some years back. This one had been rebuilt, looked superb, and wasn’t a million miles from The Shed. I had to have it. And so I did. Immediately I placed it in a far recess of The Shed and ignored it, riding all the other bikes, but not the Matchless. No idea why. Stupidity, most like. But I charged its battery, and I kicked its tyres, and when we finally moved down here to Cornwall I decided that it would be the perfect bike for the local roads. And indeed it is. Hurrah. At last.

So finally at last comes the story. The riding impression, if you prefer. Exactly what is a Matchless G15CS and why should you pawn the goldfish and buy the first one you see offered?

Loads of reasons. Ignore that stupid joke of a test in that ancient issue of Motorcycle Mechanics. You do not need to look utterly silly to ride one. Remember that Clint Eastwood also rode a Norton hybrid (oh yes he did!), and that all riders of these hybrids automatically look as cool as Clint himself. Trust me on this.

For some reason AMC, like most other trad old Brit bike builders, decided that UK bike buyers were very dull. Maybe they’d been reading Motorcycle Mechanics, in which case they are excused for so thinking. They reacted to this dullness by supplying dull versions of their motorcycles to the UK market. Compare US and UK versions of the T140 Bonneville if you doubt me. Because of this perceived dullness (and they may well have been right, of course), most of the truly tricky versions of several models were sold mainly abroad, and this was the case with the AJS / Matchless / Norton 750 hybrids. The UK touring version, the AJS Model 33 Mk2, aka the Matchless G15 Mk2, aka the Norton N15 Mk2 (although I’ve never actually heard of one of those, so the factory may never have built any) was a very ordinary looking touring twin remarkable only for the mix of AMC components.

There was a UK caff racer version, the CSR, which was an altogether more appetising prospect, featuring dropped bars, rear-set rests, swept-back exhausts, stumpy seat and a glorious be-chromed petrol tank. In fact it was a ride on one of these that convinced me that I just had to own a hybrid myself!

However, although the street scrambler CS version was theoretically available in the UK (that woeful Motorcycle Mechanics story was some sort of proof of this), the great majority of them were sold in the US. Which is why every single Matchless or Norton 750CS twin I’ve encountered has been a re-import, I guess.

But what is so remarkable about them? Why have I lusted after one for so long? Why were they never successful sales-wise in the UK?

They are remarkable entirely because they are remarkable to ride. No more than that. I’d forgotten how superb they are to ride until I got my own Matchless version back on the road. I am an idiot. I shall ride it at every opportunity to make up for lost time.

The Norton Atlas engine, the 745cc version of Bert Hopwood’s original 497cc Dominator engine, has a well deserved reputation for serious vibes. At least, it had such a rep when we told the truth and before we got too misty-eyed and nostalgic. Believe me, an Atlas can really shake. I had one, and built it into a Triton, using a pre-unit Triumph T100 engine – that’s how rough they could be! But it also has a rep for serious stomp. Norton had done something remarkable when they stretched the 647cc version out to 745, a clever something they repeated when they stretched the engine out to 828cc for the final versions of the Commando: they tuned their bigger engine for Grunt rather than for outright Go. And as all Harley-Davidson riders will tell you, Grunt is very satisfying.

Sadly, the yoof of mid-60s Britain wanted Go, and bought ever-increasing numbers of Hondas instead. Which is a shame…

Sadly, the yoof of mid-60s Britain wanted Go, and bought ever-increasing numbers of Hondas instead. Which is a shame…

When you fit an Atlas engine into a Matchless frame something odd appears to happen. All that familiar grunt is present and correct, but the vibes are remarkably subdued. There have been theories about this within the ranks of the AJS & Matchless OC, and many of them are to do with the different resonances of the Norton and Matchless frames. They may be true. Who knows? All that is important here is that the taming of the Atlas vibes enables a G15 rider to take serious pleasures from that engine’s fine reserves of stonk.

Now then, for the CS (or street scrambler, possibly) versions of the hybrids, AMC offered a lower gearing, gearing to suit any maniac who felt the urge to venture onto the deserts which the US and Australia have in abundance, for a little boonie-bashing. Indeed, these versions of the hybrid were often described as ‘desert sleds’, giving you an idea to what purpose our overseas cousins intended to put them! They must have been completely crackers, as my new MoT man, a serious off-road destroyer of modern motorcycles, remarked when he brought the Matchless back from its test ride.

But anyway, back to the gearing.

Gearing a bike for the desert, back in the 1960s, when it wasn’t possible to simply design, build and install an entire new transmission in an afternoon, meant lowering the ratios en masse by changing the engine or final drive sprockets. In practical, 2003 terms, this provided truly outstanding acceleration. Indeed, the Matchless would probably hold a Triumph Daytona in a zero to 50mph sprint. Sadly, the Matchless is just about revving its mains out at 60mph, while the Triumph has at least four more gears to go! But it all adds to the character.

So you have mucho bottom end blast, even if it’s all over at A-road speeds? Well, nearly. It is a question of sensibilities. I am assured by Those Who Know that my G15CS should cruise comfortably at 70mph-plus, but…

The Matchless also steers with predictable precision and poise. No-one I have ever spoken to agrees with me, but I am sincere in my belief that the AMC bicycle, when fitted with long Roadholder forks, steers as well as a featherbed Norton. Don’t care; I’ve owned loads of each, and I know which I prefer.

The G15CS is a fine -steering machine. It also handles as well as you’d expect, given those high, wide bars, and that slim tank, which is perfect for flicking between the knees through the tightest and most poorly-surfaced of S-bends. You can lay the whole plot over under full power, feeling the back tyre twitching away … all the time in perfect confidence. It doesn’t roll effortlessly around its back tyre in the way a modern bike does, but it’s not a modern bike.

-steering machine. It also handles as well as you’d expect, given those high, wide bars, and that slim tank, which is perfect for flicking between the knees through the tightest and most poorly-surfaced of S-bends. You can lay the whole plot over under full power, feeling the back tyre twitching away … all the time in perfect confidence. It doesn’t roll effortlessly around its back tyre in the way a modern bike does, but it’s not a modern bike.

That last comment comes back in spades when you haul up using Mr Norton’s fine anchors. This is no modern motorcycle, but its brakes are well up to the engine’s performance, although they do have a tendency to get grabby after a night parked outside in the drizzle.

Fuel consumption is dreadful, largely because acceleration is so entertaining and because of the low gearing which makes the acceleration so entertaining! I’m getting mid-30s to the gallon, which isn’t impressive, but I do not care. Sorry, I just don’t.

And it uses oil; another cardinal sin in today’s stupidly PC world. The Norton engine uses a gear oil pump to push its lube around the engine, and like most others of its ilk, once a little wear sets in oil drains down to the crankcases while the bike’s parked. You then start the bike up, and before the scavenge side of the pump can clear the oil back to the tank, those big pistons are whamming up and down, crankcase pressures are going mad, the timed breather (lives on the camshaft on these engines) can’t cope and the oil gets pushed past the driveside main bearing into the primary chaincase and then out of the open-to-atmosphere breather and onto the road. All of this I had to explain to the MoT man, as the beast leaked lube all over his shiny workshop floor … ahem.

But strangely … you forget all this once you’re flying. The riding position and suspension settings are all for a big heavy trail bike, a kind of bike that the Japanese didn’t invent until well into the 1970s, when they, along with BMW, understood that there was a decent market for one. If you like, the Matchless G15CS is the Super Ténéré’s grandad.

All of which makes it perfect – no exaggeration – for the roads of rural Devon and Cornwall. It also makes it ideal for heavy town traffic, as just like modern big trail bikes, the power is immediate, low down and punchy; the handling is very light once you’re on the move, and the brakes are adequate. It also makes an enormous amount of noise and looks magnificent, all of which should help prevent the plonkers from pulling out in front of you!

Does it have faults? Yes of course. All bikes are compromised to some extent. The Matchless suffers from that low gearing. I do not fancy riding it on a motorway (although I rode it down maybe a hundred miles of M6 once, it was not a great experience). It is noisy. Not everyone revels in the sound of a barely-silenced 750 twin. I do, but…

…but this is a splendid motorcycle. They are so splendid and so quirky that owners tend to collect them, to become anorak about them, and to gather together in small mutter huddles. That’s all right then.

Before we could take the photos which you see here, the G15 simply demanded to be cleaned. It came to Cornwall in the yakking rain, and then stood in a damp shed for two months, poor thing. Just about every metal bit needed a once over before you could wave a camera lens anywhere near it.

Congratulations should go, then, to Armours, who supplied the exhaust pipes. There was not a spot of rust anywhere on them; not even on the welds or at the very end of the silencers where condensation loves to lurk. Good kit!

The same can’t be said about some of the bike’s ancillary equipment – maybe the kickstart and gearchange levers were old ones? They had certainly grown an unhealthily scabrous coating of oxide. It cleaned off, mostly, with the application of elbow grease, but experience tells me that it’ll re-appear the very next time this bike meets rain. It’ll need constant vigilance to keep those items from turning orange and ‘orrible, oh yes.

The same can’t be said about some of the bike’s ancillary equipment – maybe the kickstart and gearchange levers were old ones? They had certainly grown an unhealthily scabrous coating of oxide. It cleaned off, mostly, with the application of elbow grease, but experience tells me that it’ll re-appear the very next time this bike meets rain. It’ll need constant vigilance to keep those items from turning orange and ‘orrible, oh yes.

And sadly, the same is true of the wheel rims. The NEW wheel rims. The chrome on them is pocked and pitted ALREADY. This bike came straight from its restoration and into our clutches, and apart from the recent travails it’s been well kept. Yet a new set of wheels are fast on their way out. I can’t find any receipts to confirm who supplied the wheels, but they are stamped ‘CWC.’

If FW decides to ride this bike regularly then he’ll have to make a decision about what to do with them; they’ll need remedial action very soon. Shame, eh?

Classic and British bikes like this one appear every month in the pages of RealClassic magazine. Our in-depth articles by expert and enthusiast authors reflect the old bikes we buy and ride in the real world: frequently fabulous; occasionally awful, but always interesting…