If you want to see a motorcyclist’s eyes glaze over, just mention the phrase, ‘three wheeler’. His mind will fill with images of turgid plastic bodied vehicles which only exist because a quirk of British law exempts their owners from passing a motor car driving test. But there are exceptions. Utter the magic words Aero Morgan, and his eyes will either light up with enthusiasm or turn green with envy. On the other hand, talk with confidence about a James Samson delivery van and he will probably stare in disbelief.

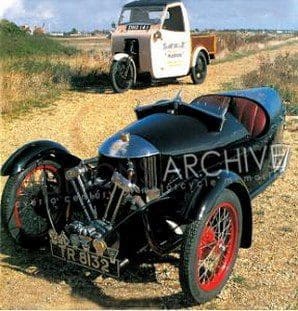

Do you doubt my ophthalmic analysis? Perhaps you think that motorised tricycles have no place in a motorcycle magazine? Then you weren’t at Beaulieu, Hampshire, last August for the Graham Walker Run — held each year in memory of that lifelong motorcyclist and editor of The MotorCycle. Amongst a glittering array of elderly vehicles, this Morgan was awarded the ultimate accolade — the riders voted, it the most desirable machine present. The ‘James was there too, and drew a permanent crowd of men intrigued by its rarity, and women attracted by its Thomas the Tank Engine cuteness.

The James has been a regular sight since restoration by the late Salisbury enthusiast/dealer, Charlie Knight. On loan to Sammy Miller’s Hampshire museum for several years, it is now there permanently.

The Morgan lives just round the corner from Sammy’s museum, and is owned by Wally Walter, a motorcycle enthusiast from way back. Building an ultra successful business career — among other things he was a founding director of British Caledonian Airways — caused Wally to neglect his hobby for some years. But after retirement he was determined to fulfil a long standing ambition of owning a JAP-engined Aero Morgan. So when the Scottish enthusiast who had totally restored this beauty advertised it 18 months ago, Wally didn’t hesitate. He jumped on the next plane north and bought the Morgan.

The Morgan lives just round the corner from Sammy’s museum, and is owned by Wally Walter, a motorcycle enthusiast from way back. Building an ultra successful business career — among other things he was a founding director of British Caledonian Airways — caused Wally to neglect his hobby for some years. But after retirement he was determined to fulfil a long standing ambition of owning a JAP-engined Aero Morgan. So when the Scottish enthusiast who had totally restored this beauty advertised it 18 months ago, Wally didn’t hesitate. He jumped on the next plane north and bought the Morgan.

He says: “The Morgan needed very little work, other than to titivate its appearance. I’ve got the complete lighting set ready to fit, but it’s such fun to drive that I don’t want to take the Morgan off the road.” One job he is attending to is replacing the near-side radiator shield.

“I drove nearly 1000 miles on appalling roads in the Irish Rally earlier this year,” he grins, “and the shield dropping off was almost the only problem”. In fact half of the spokes in the rear wheel also broke, but this is apparently such a frequent result of driving Morgans hard that Wally thought it hardly worth mentioning.

At first sight, the two test machines have nothing in common other than V-twin engines and three wheels apiece — even those are arranged differently. What they do share, however, is their precarious perch in the outer branches of their evolutionary trees.

Nowadays, we tend to see three wheelers as a design compromise, but in earlier days tricycles existed in their own right. Imagine yourself as Edward Butler, making the very first British petrol driven vehicle in 1887. Three wheels was the obvious layout. Life was difficult enough without building a motorised bicycle, whose balance had to be controlled and which could fall over, and why go to the expense and complexity of using four wheels?

Nowadays, we tend to see three wheelers as a design compromise, but in earlier days tricycles existed in their own right. Imagine yourself as Edward Butler, making the very first British petrol driven vehicle in 1887. Three wheels was the obvious layout. Life was difficult enough without building a motorised bicycle, whose balance had to be controlled and which could fall over, and why go to the expense and complexity of using four wheels?

HFS Morgan adopted the three wheel layout right from his first design in 1910. By the end of the vintage period, the Morgan’s combination of performance, simplicity and stability was available with a wide range of water and air cooled V-twin engines. Bodywork could be in the streamlined Aero style, or the more staid Family version. In 1933 the company bowed to demands for increased sophistication, and an urbane four cylinder car engine became available. The Morgan gained in complexity without any improvement in performance, and three years later the four wheel version inevitably arrived. The sports tricycle was finally phased out in 1950, its glory days forgotten. Modern equivalents are only made by small specialised firms.

The James illustrates a different approach. By the Twenties, motorcycles had ample power to haul commercial loads. But rather than bolt a sidecar on the side, why not hang a load-carrying body on the back? Early James three wheelers did just that. The truck featured here has progressed to a car-type chassis, but it — and the better known Raleigh Safety Seven/Reliant — retain an essential simplicity. As with the Morgan, the Reliant concept was eventually developed out of all recognition. The motorcycle with an extra wheel had suddenly become a car with a wheel missing. But in countries as far apart as Italy and India, the lightweight commercial tricycle is still a common sight.

Workaday use

Studying the two machines side by side, it is obvious that the James was intended for workaday use. The wheels are fully interchangeable and a spare is provided. There are also windscreen wipers — admittedly they are hand operated — but there is thoughtfully a blade on each side of the screen so that rain and condensation are cleared simultaneously.

The engine may be firmly based on James’s motorcycle products, but it has the benefit of car type electrics with coil ignition. However the 1100cc side-valve V-twin betrays its motorcycle magneto powered origins – it has to be stopped by a valve lifter mounted outside the cab.

More fundamentally, the Jimmie has a car-type three-speed and reverse gearbox, while the Morgan has its gear lever out in the breeze there’s no room inside the cockpit — operating simple dog clutches which select one or the other of just two chain driven ratios.

So, it’s round one to the delivery van. But what are they like to drive? Again the James gets off to a flying start. The doors open wide, and there is plenty of space inside the cab on the hard bench seat. The engine starts readily on the self starter and quickly settles down to a steady, if earth shaking tickover.

The motorcycle type girder front fork is operated by a short link from the steering column and the truck turns in little more than its own length. Even without a reverse gear, getting in and out of tight spaces would be a doddle. Initial acceleration is good, and top gear pulls strongly from around 20mph.

Now contrast the Morgan. For a start, you won’t even get into the driver’s seat unless you are reasonably slim and agile — there are no doors you see. Worse still, you have to sit on the boot lid while manoeuvring your legs under the steering wheel

Now contrast the Morgan. For a start, you won’t even get into the driver’s seat unless you are reasonably slim and agile — there are no doors you see. Worse still, you have to sit on the boot lid while manoeuvring your legs under the steering wheel

Next set the oil feed. As late as 1930 the JAP engine still relied on a hand-pumped drip feed located on the dashboard. And then you adjust the hand controls for advance/retard, choke and throttle. Finally, start the engine. Fortunately this Morgan has a self-starter — a £10 optional extra — more typically your passenger would be forced to run round the front and wield the starting handle.

If you have parked too close to an obstruction you then have to be pushed backwards (reverse gear finally became available on Morgans in late 1931). The turning circle is pretty poor and you will need a multi-point turn before the Morgan is aiming in the right direction. Your exhausted passenger then clambers aboard whereupon you are both immovably wedged in place. At 32in the cockpit is a full 14in narrower than the James’s.

Visibility is dreadful compared with the tall commercial vehicle. In the Morgan your eyes are level with the offside mudguard, while the nearside wheel is invisible beyond the bonnet.

Anyone notice a slight bias so far? Fear not, Morgan fans, the balance is about to be redressed.

No three wheeler is going to give a brilliant ride. Three points of ground contact might be ideal for a milking stool, but on a road vehicle the single wheel is bound to catch all the bumps. On the Morgan, the fairly supple springing (Morgan’s idiosyncratic sliding pillar front suspension is good enough to be used on their modem sports cars) copes reasonably well. But on the high and narrow James, the springs are designed to cope with a commercial load equal to the truck’s own weight. At any speed on a rough road it lurches and crashes nauseatingly from one wheel to another. The impression of impending doom is heightened by protesting creaks from the largely wooden bodywork.

But what of the extra gears on the James? Well, they’d be handy for house-to-house deliveries of milk or coal, but in normal driving the torquey V-twin seldom needs anything other than top gear. As with contemporary car gearboxes there is no synchromesh, and downward changes require double declutching (if you don’t know what that is, ask your grandad). Since the three pedals are squeezed into a mere 9in footwell, their control demands the nimbleness of Rudolph Nureyev. In contrast, the seemingly crude Morgan system provides a quicker change.

But what of the extra gears on the James? Well, they’d be handy for house-to-house deliveries of milk or coal, but in normal driving the torquey V-twin seldom needs anything other than top gear. As with contemporary car gearboxes there is no synchromesh, and downward changes require double declutching (if you don’t know what that is, ask your grandad). Since the three pedals are squeezed into a mere 9in footwell, their control demands the nimbleness of Rudolph Nureyev. In contrast, the seemingly crude Morgan system provides a quicker change.

Turning the Morgan ceases to be a problem once you learn to park on uphill slopes. Then you can roll back to face the other direction.

Still, the James has better weather protection doesn’t it? Well, you are shielded from direct rain, but the lack of side windows means that the wind howls round your ears far more than in the cosy cockpit of the Morgan. You do get a little warmth from the engine, but you pay for it with the cacophony. The James is not as loud as air-cooled V-twins go, but sharing a cab with an engine is very different from sitting astride one on a motorcycle. The JAP engine on the Morgan is naturally quieter with its water jacket — anyway the mechanical noise is lost on the wind. All you hear is the glorious raucous bark of the twin fishtailed exhausts.

Easily locked rear wheel

The Morgan originally had front brakes operated by a hand lever with the foot brake only acting on the easily locked rear wheel. But on this model the setup has been reversed, so at maximum force can be applied where it will be most effective. Wally reports that this objective has been achieved, but it is difficult to keep the cable operated front brakes balanced. Sometimes the Morgan pulls to one side.

The sportster needs good brakes because it was seriously swift for its day. The James pick-up-will do 50mph or so – provided you have ear plugs and the nerves of a stunt driver – but the sports three wheeler is half as fast again, and has precise steering and leech-like road holding, inviting you to exploit its performance. The only deterrent is that with its ground scraping seating position, you feel as if you are doing motorway speeds while in truth you are observing with the urban limit.

The one difficulty with driving the Morgan – surprisingly, since it is the feature which should be familiar from riding vintage motorcycles – is the hand operated throttle mounted on the steering wheel. You would be surprised how difficult it is to locate that lever when the wheel is turned — let alone to move it in the correct direction. This is not just my ineptitude; both Motor Cycling and Light Car and Clyclecar made similar comments in 1930, pleading for a foot throttle.

The contrasts between these two vehicles are obvious, but it seems to me that both were well matched to their allotted roles. Despite its car like appearance, the Morgan drives like a three wheeled motorcycle, full of fun and character but needing real skill to use effectively. The agricultural looking James on the other hand emerges as a wholly functional vehicle, yielding nothing to contemporary four wheeled vans either in its usefulness or in ease of driving. What a pity that a misguided search for sophistication caused British manufacturers and customers alike to lose sight of the market potential for the purpose built three wheeler.