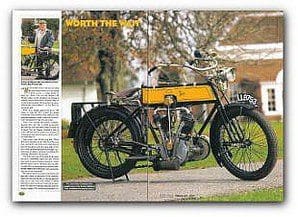

“We’ve decided not to sell you the BAT. My wife doesn’t think you can afford it while you’ve a young family to bring up.” Hmm. You can just imagine Sid Moore’s panic as the prospect of owning a possibly unique and historic veteran began to recede from his grasp. But he perked up somewhat as the owner added “….so I’ve left it to you in my will.”

There were strings attached however. Sid wasn’t to take the BAT outside the parish boundaries of his Sussex home unless he was riding the machine. And he was never to sell it, but to bequeath it to his own son John.

These were strange stipulations considering that John was only a toddler at the time and that the BAT had spent part of its life in Scotland. But the biggest drawback was to come. Sid then had to endure two decades of watching his prize deteriorate in a shed before he could claim it.

Some good came of this long wait. When Sid took possession in the mid-Seventies, son John had grown up to become interested in old vehicles and is now the usual rider of the BAT. While Sid is remarkably fit and agile, running starts on large V-twins are not advised for vertically challenged 78-year-olds.

“The BAT was in an awful state by the time we got it,” remember father and son. “It had been used to move chicken houses on a farm and the frame was so distorted that the tank wouldn’t fit in it. It had also been used as a stationary engine and it still had a big cooling fan attached to the crankshaft.”

The engine had to be totally refurbished. Sid and John cringe at memories of the crankpin which had been replaced by a big nut and bolt built up to size with soft solder. A friend machined a new pin from a Land Rover drive shaft. The big end bearings originally featured floating bushes. With insufficient metal left for safe machining, new bushes were permanently fitted into the conrod eyes.

The engine had to be totally refurbished. Sid and John cringe at memories of the crankpin which had been replaced by a big nut and bolt built up to size with soft solder. A friend machined a new pin from a Land Rover drive shaft. The big end bearings originally featured floating bushes. With insufficient metal left for safe machining, new bushes were permanently fitted into the conrod eyes.

The pair straightened the frame, and managed to restore most of the cycle parts, but the tank had to be replicated by a local tinsmith. Fortunately he was able to reclaim the unique trapdoors in the tank’s centre which allow access to the magneto. BAT’S 1907 advertisement boasted: ‘Note how the magneto is protected from the mud. Personally, I’d rather keep it away from the petrol. I hope Sid keeps his fire insurance up to date. The distinctive tank colour was painstakingly chosen to match an artist’s impression in a magazine, and Sid was mortified to subsequently learn that it should actually be silver.

Old vehicles

Repairing old vehicles is nothing new for Sid Moore. When WW2 was declared he was a 21-year-old in hospital recovering from a smash on an Excelsior. With a permanently bent left arm, he was declared unfit for military service and the Ministry of Supply set him to maintain cars, lorries and tractors. He received no formal training, but learnt enough to spend the rest of his working life on tractor maintenance. Soon after the end of the war he started collecting historic motorcycles. “I was afraid all those marvellous old bikes would disappear before John was old enough to appreciate them,” he says.

His first real restoration — in about 1960 was a veteran V-twin Matchless which has appeared in most subsequent Pioneer Runs. Sid has designs on the highest combined age award, although he concedes that he will have to “keep going for a few years yet”

His first real restoration — in about 1960 was a veteran V-twin Matchless which has appeared in most subsequent Pioneer Runs. Sid has designs on the highest combined age award, although he concedes that he will have to “keep going for a few years yet”

Once the BAT’s JAP engine was mechanically restored, Sid and John had a lot of trouble getting it to run properly because of its primitive nature. It has automatic inlet valves, where — scientifically speaking — atmospheric pressure does the work In normal language, the valves are sucked open as the piston descends, and closed as the piston rises again — blissfully simple when properly set up, but it is devilishly tricky to select springs which allow the valves to open easily and assist them to close at the correct instant.

Teething troubles dogged the BAT on its inaugural Pioneer Run in the Eighties. It misfired badly, but Sid struggled on, eventually reaching Brighton enveloped in a cloud of smoke and looking like a chimney sweep. He and John discovered that an inlet spring had apparently disappeared. Incredibly, it had passed right through the carburettor’s inlet tract and ended up inside the other cylinder head. The smokescreen resulted from the way the misfire deranged the crankcase suction which draws oil from the front of the tank via a needle valve.

Automatic valve operation was passing out of favour even when the BAT was new in 1908, and this one is possibly a unique survivor of its type. It was an early participant in the Pioneer Run, and in 1932 was ridden — with a sidecar attached — by one Eric Staines Oliver, years before he became a champion racer on three-wheels. The Run programme stated: “After an adventurous life in Scotland and London up to 1927, the ancient wandered down into Sussex, and has since been cutting chaff and doing other farm work.”

It’s amazing that after such early recognition of its historical importance, the BAT should again be pressed into farm duties before Sid Moore rescued it.

Apart from its valve gear, the BAT was very advanced, with suspension at both ends. There are leading links at the front, and the saddle and footboards are mounted on a sprung subframe. Springing the rider, rather than the rear wheel, enabled constant belt tension to be maintained.

Starting handle

Starting was also advanced for the days when run and jump was the norm. A starting handle fits directly onto a dog clutch on a crankshaft extension. John Moore says that the handle has a distressing tendency to fly through the nearest window when the old machine bursts into life, and so he always chooses a running start. He has become so adept that he can bump start the BAT, and quickly knock it out of gear without even mounting the saddle.

Possibly the most useful feature of the BAT is an optional extra — Phelon and Moore’s two speed transmission. It fits in front of the engine, and consists of two parallel primary drives with different sprocket ratios. There are independent clutches inside both of the driven sprockets, and a single lever takes up the drive and selects the drive ratio. A similar system was used on two-speed Scotts, and the two Yorkshire companies disputed rights to it until they discovered that it had been patented years previously by a third party. Its main shortcoming is that it is impossible to tension both chains precisely.

As I take over the BAT, I am faced by a surprising lack of controls. To the left is a decompression lever, and to the right are the carburettor levers — and that appears to be it! Closer study reminds me that the clutch/gear lever is to the left of the tank, and a delightfully old-fashion wooden handle lying along the top frame tube takes care of magneto timing.

I follow John’s advice and opt for a running start which proves to be exceptionally easy. I get the BAT in motion in first gear, drop the valves and scoot alongside for a couple of paces until the gentle chuff-chuff tells me it’s time to climb on board, then I can shift into top and sit back to enjoy the steam-engine like feeling of being pushed rather than propelled.

I follow John’s advice and opt for a running start which proves to be exceptionally easy. I get the BAT in motion in first gear, drop the valves and scoot alongside for a couple of paces until the gentle chuff-chuff tells me it’s time to climb on board, then I can shift into top and sit back to enjoy the steam-engine like feeling of being pushed rather than propelled.

The BAT is no slouch It will cruise effortlessly on the high side of 30mph. The two controls on the B&B carburettor repay a bit of juggling. The engine won’t accelerate unless the air lever is closed, but once cruising, it runs even more sweetly with a bit of extra air.

There is no need to carefully coordinate throttle opening and gear selection. Once the engine is running, simply ease the lever forward and you are in motion, it is as simple as that. The gear’s position necessitates several yards of drive belt which provides all the transmission shock absorbing you could ever want.

At the other end of the scale, it will slow right down by just closing the throttle and— if necessary — retarding the ignition. Deceleration using the brakes is less impressive. The action of the left brake has been reversed to give some self-servo action. But if you need to stop urgently, then it’s time to check that the insurance is paid up. The angular top tube around the petrol tank feels a little close for comfort, so perhaps it is a good job the brakes aren’t too fierce!

The throttle is pushed away for acceleration. If, like me, you are more used to the opposite action, trying to slam it shut in an emergency will result in almost 1.1 litres of unstallable urge propelling you towards disaster. With the P&M gear, that enormous flywheel effect and low speed torque come to the rider’s assistance.

Riding comfort is excellent by veteran standards. Using a ‘cricket-BAT analogy which may have been too subtle for some of the readers, contemporary advertisements claimed: ‘A ride on a BAT spring frame makes you feel as lively as a cricket’.

Riding comfort is excellent by veteran standards. Using a ‘cricket-BAT analogy which may have been too subtle for some of the readers, contemporary advertisements claimed: ‘A ride on a BAT spring frame makes you feel as lively as a cricket’.

The freedom to concentrate on controlling the machine without worrying unduly about the atrocious road surfaces of the period must have contributed much to the marque’s formidable racing reputation. In 1903, originator Samuel Robert Batson claimed that ‘The BAT motorcycle holds all world records’. Shortly afterwards Batson went into voluntary liquidation. One of Batson’s most successful works riders, Theodore H Tessier, bought the business which survived until the mid-Twenties. Sid Moore was delighted when one of TH Tessier’s descendants visited Bentley Wildfowl Trust and Motor Museum in Sussex (01825 840573) where the BAT lives.

Keep a lookout for it on classic runs during 1999. Take the opportunity to study its rare alliance of dated engine and forward-looking frame. Owner Sid will tell you it was worth wait. View original article