It was August 1974 and the turmoil in British motorcycle manufacturing continued. Norton–Villiers–Triumph had been formed a year earlier in a bid to save jobs following the collapse of BSA-Triumph. Then the new Labour government offered £5-million to the workers fighting the decision to close Triumph’s Meriden factory, putting further strain on NVT’s finances.

Against a backdrop of widespread industrial strife and rising fuel prices after the Israeli-Egypt Yom Kippur war, NVT’s problems were a minor consideration.

But the future of British motorcycle manufacturing was at stake. With materials and stock held up at Meriden, NVT was struggling at its Wolverhampton factory. It needed support as much as the Meriden workers, and in a bid to show that it was developing machines that could compete successfully with those imported from Japan and Europe, NVT’s boss Dennis Poore allowed a number of journalists to see inside the company’s research and development centre at Kitts Green in Birmingham and reveal what it had been working on.

More powerful and better-handling Triumph triples had been expected – five consecutive TT production race wins by Les William’s Slippery Sam had assured that possibility – but excitement also surrounded a completely new Superbike that had been under development behind the scenes.

More powerful and better-handling Triumph triples had been expected – five consecutive TT production race wins by Les William’s Slippery Sam had assured that possibility – but excitement also surrounded a completely new Superbike that had been under development behind the scenes.

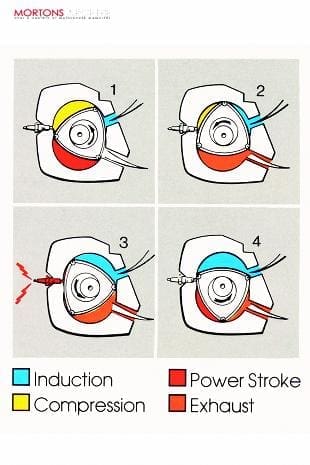

Few, if any, outside the factory had been aware that the BSA-Triumph group had been working on a Wankel-engined motorcycle since the late 60s. Indeed, that it had been toying with the idea in parallel with the development of the triples.

But out of the blue we were offered the opportunity to view and analyse a prototype and quiz the senior development engineer who had been in charge of the project for four years, David Garside. Not only that, as road tester for the weekly paper Motor Cycle, I was allowed to take the bike away for a weekend to find out how it might cope with day-to-day use.

The significance of the rotary engine for motorcycle applications was huge. By 1974 Superbikes like the Honda CB750, 900cc Kawasaki Z1, Suzuki GT750, Ducati 750cc V-twin and BSA-Triumph 750cc triple had become commonplace and we’d found that while easy 130mph performance was a thrill, it came with the penalty of weight and less-wieldy handling.

The Wankel rotary engine promised to be both more compact than a piston engine and completely vibrationless. This was a concept that I, like most motorcyclists over the years, thought to be inconceivable. On our singles and twins the finger-numbing vibration was accepted as the price of light weight and agility, but even four-cylinder machines buzzed at high revs, as did BMW’s bigger flat twins.

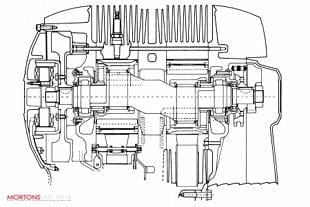

Garside’s development programme had also produced a power unit that was much lighter than equivalent reciprocating engines. The complex oil-and-liquid cooled rotary-engine efforts of Suzuki, to be launched later in 1974 as the RE-5, and Yamaha, which never reached production, Garside had refined an air-cooling system for the rotors that simplified the design of the twin-rotor unit.

Garside’s development programme had also produced a power unit that was much lighter than equivalent reciprocating engines. The complex oil-and-liquid cooled rotary-engine efforts of Suzuki, to be launched later in 1974 as the RE-5, and Yamaha, which never reached production, Garside had refined an air-cooling system for the rotors that simplified the design of the twin-rotor unit.

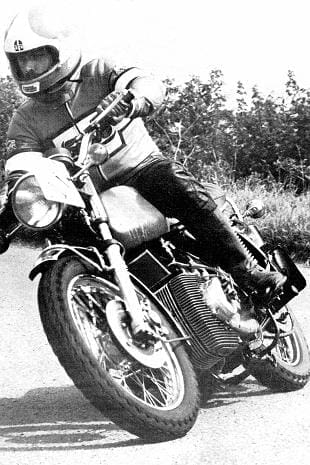

The P39 prototype offered for evaluation by NVT was the third made in Garside’s development programme. But although its engine was a completely new twin-rotor design mounted in a modified Bonneville chassis, the bike looked very much a lashed-up test bed that lacked any styling or cosmetic refinement. Fuel stains marred the tank and the exhaust system was painted a dull matt black. It was built to see if the concept worked: making it look attractive could come later.

Nevertheless, as part of the campaign to attract investors, NVT estimated that with six months’ further work it would be ready to produce a competitively priced Wankel motorcycle weighing less than 400 pounds including a starter motor and ‘will have the advantages of being vibration-free and compact with a low centre of gravity for good handling’.

From the appearance of the P39, NVT was very optimistic in reckoning on a launch in six months. But there was no doubt about the bike’s potential. After collecting the bike from Kitts Green the first task was to assess its performance at the MIRA proving grounds at nearby Nuneaton. According to the late Fred Swift, NVT’s test rider, he’d clocked a two-way average of 125mph through the speed traps on the same timing straight where all of Motor Cycle’s performance data was obtained.

From the appearance of the P39, NVT was very optimistic in reckoning on a launch in six months. But there was no doubt about the bike’s potential. After collecting the bike from Kitts Green the first task was to assess its performance at the MIRA proving grounds at nearby Nuneaton. According to the late Fred Swift, NVT’s test rider, he’d clocked a two-way average of 125mph through the speed traps on the same timing straight where all of Motor Cycle’s performance data was obtained.

But by the time I arrived at MIRA, I was already hooked. The NVT rotary prototype was a revelation. Even compared to Honda’s luxuriously refined CB500 Four that I’d tested two years earlier, the rotary was smoother and the sensation of cruising at an indicated 100mph without any vibration to buzz the rear view mirror and plenty in reserve was amazing. But it wasn’t completely vibrationless; removing the out-of-balance forces from the engine only highlighted others from the drive chain, sprockets, suspension and wheels. But the bike amply displayed its credentials as a viable Superbike.

At MIRA I was unable to match Fred Swift’s figures. But clocking a mean top speed of 119mph at 8000rpm with a standing quarter-mile time of 13.1 seconds at a terminal speed of 102.65mph was still better than the capabilities of then current 750cc machines. Garside later explained that the lower top speed was a result of porting mods aimed at broadening the mid-range power.

A key criticism levelled at rotary engines at the time was that their fuel consumption was heavier than with four-stroke piston engines. The issue was particularly acute at the time because in the wake of Yom Kippur war the fuel crisis had dramatically increased pump prices by 50 per cent from 37p to 56p a gallon.

A key criticism levelled at rotary engines at the time was that their fuel consumption was heavier than with four-stroke piston engines. The issue was particularly acute at the time because in the wake of Yom Kippur war the fuel crisis had dramatically increased pump prices by 50 per cent from 37p to 56p a gallon.

The P39 did nothing to dispel it; I carried out constant-speed consumption tests at MIRA recording 44mpg at 30mph, 42mpg at 50mph and 37mpg at 70mph, figures that made a Suzuki GT750 two-stroke triple look economic to run.

Overall, fuel consumption was 32mpg over the 650 miles I clocked on the bike, but this was more a reflection of the high average speeds. Modern unfaired sportbikes would be unlikely to better that figure at the high speeds I enjoyed.

Lubrication was similar to a two-stroke’s with oil pump fed to the inlet tracts. It only smoked slightly after starting, and consumed oil at 300 miles per pint (530 miles per litre) a figure that Garside reckoned could be reduced to 500mpp, about the same as 3000-mile oil changes on a four-stroke.

But there was plenty of other development yet to be carried out. Carburation was with a pair of 26mm Amal Concentrics and response in the mid-range was slick and certainly on a par with a Norton Commando of the time. It would pull smoothly up a one-in-four test hill from 1800rpm and provide a healthy kick from 2000rpm in top gear coming out of corners. At smaller openings it wasn’t so hot, but the earlier BSA Bandit-frame prototype fitted with constant-velocity carbs showed that sensitivity could be improved from a closed throttle. CV carbs, said Garside, would also lower fuel consumption.

By its nature, NVT’s rotary engine had low internal friction and, because of poor gas sealing at low revs, relatively little compression. That made kick-starting a challenge because of a Triumph non-unit gearbox used with a high ratio. So after flooding the carbs you had to spin the engine over quickly with a sharp flick of your boot, when you’d be rewarded with an exhaust sound rather like an angry bee.

By its nature, NVT’s rotary engine had low internal friction and, because of poor gas sealing at low revs, relatively little compression. That made kick-starting a challenge because of a Triumph non-unit gearbox used with a high ratio. So after flooding the carbs you had to spin the engine over quickly with a sharp flick of your boot, when you’d be rewarded with an exhaust sound rather like an angry bee.

Handling was brilliant, mostly because the engine’s weight was low, allowing the conventional Bonneville’s frame to be stiffened with a large-diameter tube connecting the steering head and swinging arm pivot. Wondering why cornering response was better on left-handers I checked the wheel alignment to find it miles out, but the excellent roadholding was otherwise unaffected.

Apart from the nuisance of having to repair a blown exhaust header, mostly a result of the high exhaust temperatures, the weekend with the NVT Rotary was one of my most enduring memories of testing bikes in the 70s.

Sadly, despite Dennis Poore’s efforts, NVT went bust at the end of 1975. But the rotary project continued with Norton Motors (1978) Ltd based at Shenstone in Staffordshire and still directed by David Garside.

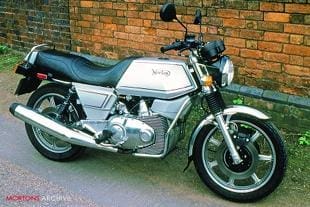

Progress towards production of the now Norton rotary was being made and in 1980 I heard soon after joining Which Bike? as editor that a launch was imminent. I contacted Bob Trigg, the co-designer of the Norton Commando who was with the company, to find out more. But during a clandestine meeting he couldn’t provide any press material, only a view of a monochrome picture showing a roadster that was ready for production and attractively styled. This was photographed to provide source information for an illustration to be produced for publication. Inexplicably, the launch was cancelled and it was another four years before the first commercial Norton Rotary was offered, but only for police and escort applications.

It was only after Norton Motors (1978) was sold to Philippe Le Roux in 1988 that a rotary Norton for civilian use was offered. It was called the Classic, made as a limited edition of 100 machines and though a roadster similar to the one I’d been shown eight years earlier by Trigg, had none of the style. And a spin on the bike revealed that to seriously compete with bikes like the recently introduced Honda CBR600 four it would have to perform much better.

It was only after Norton Motors (1978) was sold to Philippe Le Roux in 1988 that a rotary Norton for civilian use was offered. It was called the Classic, made as a limited edition of 100 machines and though a roadster similar to the one I’d been shown eight years earlier by Trigg, had none of the style. And a spin on the bike revealed that to seriously compete with bikes like the recently introduced Honda CBR600 four it would have to perform much better.

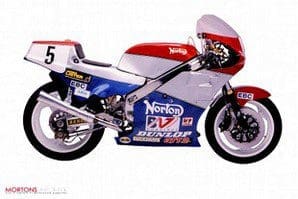

By now, the racing version developed by Brian Crighton had been campaigned successfully on British tracks (even winning a TT) so the Seymour-Powell styled Norton F1 promised much when it was launched in 1990. This uses a revised liquid-cooled engine and a Yamaha five-speed gearbox matched to a Spondon aluminium-alloy frame and White Power suspension. With a price tag of more than £13,000 it was touted as a collector’s piece. In prototype form it looked exciting, but when I tested a production version the performance was only a match for the average 600cc sportbike and the build quality was poor.

With better funding, the rotary engine could still be developed into an exciting motorcycle. But without sales largely driven by track success on a world scale, few, especially those who have a passing knowledge of the Norton rotary, would ever back a project with such a sad history.

Norton rotary history

Norton rotary history

The development of a rotary-engined motorcycle in Britain originated in the mid-60s before the Japanese factories had launched their first Superbikes.

Already being used by NSU and Mazda in their cars, the engines that had been conceived by Felix Wankel in the 1950s were seen by the BSA-Triumph group as an alternative to multi-cylinder engines.

The group didn’t have a licence to develop the rotary engine, but its research centre had been working with Fichtel & Sachs, a German manufacturer, which provided the components through its agreement with Audi-NSU. After initial investigations the first working prototype was produced in the late 60s with a modified 294cc KM914 air-cooled rotary engine mounted in a frame from the BSA A65 twin.

But because Fichtel & Sachs only had a licence for low-power rotaries, in mid-1972 BSA-Triumph obtained a licence with Audi-NSU costing £129,000 (reportedly paid for by a car manufacturer) to develop an engine of between 35 and 60bhp.

With the group’s development being concentrated at Umberslade Hall the next prototype produced between 1971 and 1972 used a rotary engine with twin charge-cooled rotors which was fitted into a chassis destined for the BSA Bandit and Triumph Fury 350cc twins and coupled to a pre-unit Triumph gearbox.

The next prototype, the P39 made in early 1974, was based on the modified oil-in-frame chassis from the 650cc Triumph Bonneville. Two versions were made with a variety of carburettors and exhaust systems, one being the machine that was released to journalists to provide publicity for the project. A bike using parts from both bikes has been restored and is in Germany.

The next prototype, the P39 made in early 1974, was based on the modified oil-in-frame chassis from the 650cc Triumph Bonneville. Two versions were made with a variety of carburettors and exhaust systems, one being the machine that was released to journalists to provide publicity for the project. A bike using parts from both bikes has been restored and is in Germany.

Development continued with these as the failing BSA-Triumph group was absorbed into Norton Villiers to form NVT, but by 1977 this too had gone into liquidation. The rump of the group, Norton Motors (1978) Ltd, continued rotary development at Shenstone, Staffs, where another prototype was produced in 1979 with limited production in mind. This featured a revised twin rotor engine with the primary drive on the right side, a five-speed Triumph T140 gearbox and a box-section frame.

Despite promotional literature being printed, a US press debut planned and, it is said, enough components for 25 machines being sourced, the launch was cancelled. The air-cooled Norton rotary engine did however go into production with the P41 Interpol II equipped for police work in 1984, of which 384 were made over five years. As power was increased during development so did heat and component failures, which is why a liquid-cooled P51 prototype was produced in 1984.

‘As power was increased during development so did heat and component failures, which is why a liquid-cooled prototype was produced in 1984 called the P51’

Financial problems continued to dog Norton Motors (1978) despite its diversification into aircraft engines and in 1988 it was sold to Phillippe Le Roux who incorporated it with a number of other companies under Norton Group plc.

First move was to produce a civilian road bike based on the Interpol II. This was the P43 Classic using the air-cooled engine in a roadster format without a fairing and offered as a limited-edition run of 100.

This was followed by the first liquid-cooled model to reach production: the P52 Commander in 1989. Styled by product designers Seymour-Powell and featuring a number of Yamaha components such as wheels and brakes, this was originally designed as a police machine but with the initial success of the Classic it was also offered as the P53 tourer. Some 309 Commanders of bike types were made.

To cash in on the racing success of Norton rotaries, the exotic and expensive P55 Norton F1 was produced with a light-alloy beam frame housing the water-cooled engine, now with a five-speed gearbox from a 998cc Yamaha. Styled by Seymour-Powell, more than 100 were produced before the money ran out and in 1991 the financial plug was pulled on Le Roux’s empire.

To cash in on the racing success of Norton rotaries, the exotic and expensive P55 Norton F1 was produced with a light-alloy beam frame housing the water-cooled engine, now with a five-speed gearbox from a 998cc Yamaha. Styled by Seymour-Powell, more than 100 were produced before the money ran out and in 1991 the financial plug was pulled on Le Roux’s empire.

An attempt was made to continue production by a team comprising former Norton factory tester Bob Rowley, former development engineer Richard Negus and Joe Seifert who owned the Norton rights in Germany. They produced the P55B F1 Sports which was a more faithful reproduction of the Superbike racers being campaigned by the JPS team. But while 66 machines were produced they were sold off by the bank’s liquidator.

Remnants of the rotary machine enterprise were sold on and during an auction at the Shenstone in 2003 were acquired by Negus, who been involved with the project at NVT and had with Seifert registered the Norton Motors Ltd company name in 1996. In 2004 he used it as the basis for a 2000sq ft operation at Rugeley in Staffordshire to provide spares and servicing for those of the 1000 Norton rotary machines made that still exist.

It has no connection with the Norton Motorcycles business set up by Kenny Dreer in Oregon, USA, that was developing a modern version of the Commando twin. The company ran out of cash in April 2006 and a buyer for the assets and rights is still being pursued.

The aviation applications of the rotary engines originally developed by Norton continue. UAV Engines acquired the rights to make units for unmanned air vehicles and operates from Norton’s former factory at Lynn Lane, Shenstone. German-owned Mid-West Engines has produced a rotary power unit for light aircraft since 1996 from its base at Staverton near Gloucester.

? See Key rotary dates

? More information from Norton Motors Ltd.