In the space of just 10 years, spanning the 60-70s, Suzuki’s T500 twin turned evolution on its head. What was launched as the hottest high-performance two-stroke twin on the block ended up as a mild-mannered tourer.

The bike appeared at the beginning of one of the most dramatic periods of motorcycle development. The two-wheel world was being turned upside down as the British domination by factories such as AJS, BSA, Triumph, Matchless, Norton and Velocette was usurped by the Japanese factories of Honda, Kawasaki, Suzuki and Yamaha.

Development of new machines advanced so quickly that the first modern big bikes launched by the Japanese onto the international markets – fantastic though they were – were quickly made obsolete as sporting machines with the quick introduction of even better models.

And so it was with Suzuki’s first heavyweight twin. Imagine yourself in the mid-60s as a young rider – as I was – and finding that riders on Japanese 250cc two-strokes could outrun your 600cc four-stroke Norton Dommie twin with ease. And then to hear that an apparently more potent 500cc version was on the way. If the tiddlers could blow you into the weeds, what could this thing do?

When Suzuki’s 492cc twin was revealed in 1967 for the domestic Japanese market it looked like a 250cc T20 Super Six on steroids. Styling followed Honda’s lead in the CB450 ‘Black Bomber’ with a rounded, chrome-paneled fuel tank and side panels plus a seat featuring studs around the edge. And what caught my innocent eye was that while it offered a claimed peak power of 47bhp – as much as any Brit 650 of the day – the price was going to be more accessible. With none of the complexities of the CB450’s double-overhead cam engine, it seemed a dream.

Similarities with the smaller Suzuki twins were obvious, but deeper than expected. Overall the bike was bigger with a longer 56.5-inch wheelbase. To accommodate the higher performance, a 19-inch front wheel and a larger 4.00 tyre for the 18-inch rear were fitted. Even the drum brakes, including the twin-leading shoe front stopper, where much the same, although this would bring criticism in later years. Dry weight was a claimed 412 pounds.

With huge finning on the cylinders the engine looked sexier than its smaller siblings. The fins were necessary to accommodate the 70mm bores but the crankcases weren’t much bigger, suggesting the pitch between the pots hadn’t been much enlarged.

With huge finning on the cylinders the engine looked sexier than its smaller siblings. The fins were necessary to accommodate the 70mm bores but the crankcases weren’t much bigger, suggesting the pitch between the pots hadn’t been much enlarged.

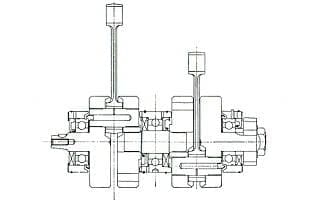

It remained a classic two-stroke, with conventional piston porting: no disc valves, reed valves or the like to enhance, or clutter the design. Typically, the horizontally-split crankcases contained a pressed-up crankshaft running on three ball bearings with a gear drive to the clutch basket. Five, rather than six, speeds were used in the gearbox with the final-drive chain on the left side.

To keep the unit as compact as possible, the cylinder porting – inlet, exhaust and two transfers – was rotated outwards so that the transfers could be kept as large as possible and resulting in the exhaust ports being positioned outside the front frame tubes. Steel cylinder liners were pressed into the light-alloy barrels. Two 32-mm Mikuni carburettors provided the mixture with filtration through a paper element.

Electrics were also simple, the 12-volt Kokosan generator using six coils, four of which were switched into the circuitry when the lights were on, not that the headlamp offered much power from 35 watts. Ignition used coils triggered by contact breakers. Nice and simple.

Lubrication for the engine’s internals was more sophisticated than Yamaha’s feeding of oil into the inlet tracts. Oil from the tank was delivered by a gearbox-driven pump by plastic tubing to the outer main bearings and the rear face of the cylinders. Oil from the main bearings was collected by a lipped plate on the outer faces of the crankshaft webs and trickled through to the needle-roller big ends. Because the engine needed more oil when under load, typically with larger throttle openings, the oil pump’s stroke and therefore delivery rate was increased by a cable connected to the twistgrip.

Like the small Suzukis the kick lever was – unusually – on the left side, calling for MZ-style starting procedures for the non-ambidextrous. Also novel was the gear-change mechanism, which used a shaft that enabled the gear lever to be fitted on either side. The brake lever could also be swapped over.

Like the small Suzukis the kick lever was – unusually – on the left side, calling for MZ-style starting procedures for the non-ambidextrous. Also novel was the gear-change mechanism, which used a shaft that enabled the gear lever to be fitted on either side. The brake lever could also be swapped over.

Performance was less lively than expected when T500 was launched in the US in 1968 but was more than enough for the chassis, and to calm it down the wheelbase was extended to 57 inches with a longer swingarm for the first incarnation, the T500II which was called the Titan in the US and the Cobra in Europe. Styling was also updated in line with the rest of the Suzuki range with a slimmer fuel tank with brighter colours matched to a wider braced handlebar.

But by 1969 the competition had upstaged Suzuki. Kawasaki launched its fiercesome 500cc Mach III triple, BSA and Triumph their 750cc triples and perhaps most daunting of all, Honda topped the lot with its CB750 four.

In comparison, the T500 had been repositioned by the opposition as a relaxed all-rounder. But it was a sweet with a hard centre. Although earlier in the 60s Suzuki had quit racing with a works team in the GPs, it still produced racers like the XR05 and Barry Sheene’s earliest successes were on a Seeley-framed development of this bike. Water-cooled versions were offered that provided the platform for riders like Jack Findlay who led a one-two for Suzuki at the 1971 Ulster GP and two years later won the Isle of Man Senior TT.

When tested by the weekly Motor Cycle in January 1971 the next version of the T500, the MkIII, was described as virtually identical to the MkII apart from a revised fuel tank with a luggage grid and a simulated fabric panel on the top and a better grab handle for pulling the bike onto the centre stand. Inside the engine, the gearbox was altered to enable bottom gear to be selected from second directly rather than having to dab the pedal twice. No mention was made that wheelbase had also been extended by another two inches to 59 inches with an even longer swingarm.

When tested by the weekly Motor Cycle in January 1971 the next version of the T500, the MkIII, was described as virtually identical to the MkII apart from a revised fuel tank with a luggage grid and a simulated fabric panel on the top and a better grab handle for pulling the bike onto the centre stand. Inside the engine, the gearbox was altered to enable bottom gear to be selected from second directly rather than having to dab the pedal twice. No mention was made that wheelbase had also been extended by another two inches to 59 inches with an even longer swingarm.

Now called the Charger, the bike was described by David Dixon, my predecessor at the newspaper, as an extremely exhilarating bike to ride with performance that put comparable roadsters in the shade. Compared with the ‘rhythmical slogging’ of a four-stroke single and the buzziness of a four-stroke parallel twin, the Charger offered ‘surging acceleration’ with a standing quarter mile time of 14.2 seconds and a terminal speed of 88mph.

For high cross-country speeds, the Charger was up to the task, but the engine needed to be kept above 4500rpm with gear changes at 6000. Likewise the high handlebar and the forward position of the footrests made sustained high speeds a strain on the rider. Vibration from the engine, which in later years might generously be described as intrusive despite the use of rubber mounts for the handlebar, ‘would scarcely be noticeable to anyone accustomed to a parallel twin four-stroke’. Scant praise!

For high cross-country speeds, the Charger was up to the task, but the engine needed to be kept above 4500rpm with gear changes at 6000. Likewise the high handlebar and the forward position of the footrests made sustained high speeds a strain on the rider. Vibration from the engine, which in later years might generously be described as intrusive despite the use of rubber mounts for the handlebar, ‘would scarcely be noticeable to anyone accustomed to a parallel twin four-stroke’. Scant praise!

Peculiarly, the bike was also said to be over-geared in top, even though it was revving to more than 7000rpm, the peak power revs, at the maximum speed of 103mph recorded on MIRA’s test strip.

This was no problem at lower speeds or in town where the flexibility of the engine could be exploited with less use of the gearbox, pulling easily from 2500rpm in top though accompanied by induction drone. In town use, fuel consumption was 55mpg but with fast open road use this dropped to 39mpg giving a range of just 110miles before reserve. The brakes were ‘extremely effective’.

Time passed but for the T500 nothing much changed, apart from its Cinderella status in the Suzuki range where it was positioned as a value for money model. By 1975, Suzuki’s range of two-stroke 380cc, 550cc and 750cc triples were well established and the T500’s shortcomings were too obvious to ignore. More to the point, a range of four-strokes was under development at the factory to meet emissions regulations. A new version of the 500cc two-stroke was launched with a number of improvements aimed at reinforcing its personality, bringing it in line with other bikes in the range and perhaps revitalising its showroom appeal.

Called the GT500, it came with a front fork and hydraulic disc brake similar to the GT550 triple’s that altered the wheelbase again. Fuel tank was the larger version from the GT750 and the headlamp instruments were brought up to date.

Suzuki’s engineers also changed the engine to emphasis its torquey character. Porting in the cylinders was modified along with longer inlet tracts to boost the throttle response at lower revs. Peak torque was raised to 38.3 lb-ft at 5500rpm, 500rpm lower in the rev range but at the expense of peak power that topped out at 44bhp at 6000rpm. It was also brought up-to-date with electronic ignition replacing the points.

Suzuki’s engineers also changed the engine to emphasis its torquey character. Porting in the cylinders was modified along with longer inlet tracts to boost the throttle response at lower revs. Peak torque was raised to 38.3 lb-ft at 5500rpm, 500rpm lower in the rev range but at the expense of peak power that topped out at 44bhp at 6000rpm. It was also brought up-to-date with electronic ignition replacing the points.

Result was that the engine would happily lug from 2000rpm, making it even more relaxed to ride at moderate speeds. Not much was lost from the top end, with the engine running out of steam from 6200rpm.

This meant that the top speed at MIRA was largely unaffected, topping out at a mean 104mph at 6300rpm. Flat out acceleration through the gears was dented, however, simply because there was less power. The slower mean two-way figure of 15.15 seconds with a terminal speed of 86.98mph wouldn’t necessary worry most owners because few would be using the bikes for flat out performance.

Vibration would do it for them anyway. ‘Very nasty,’ was the way I described it at the time. Despite the changes, the engine’s age was beginning to show, with piston rattle exposing the air-cooled unit’s inner simplicity.

Vibration would do it for them anyway. ‘Very nasty,’ was the way I described it at the time. Despite the changes, the engine’s age was beginning to show, with piston rattle exposing the air-cooled unit’s inner simplicity.

I found the GT500’s handling strange as well. The combination of low weight, long wheelbase and crude suspension called for more effort in bend swinging than you’d expect, and a slow roll would set in over ripples. I found the riding position with the footrests positioned too far forward awkward, but conversely others on the magazine thought it was okay.

Indeed, two years later in 1977 Suzuki, no doubt keen for any positive publicity for the bike, provided one for long-term test. Colleague Stewart Boroughs took it to the West German GP at Hockenheim, covering more than 1300 miles, mostly on autobahns. Never one to pussy-foot, Stewart cruised at 75mph but it never missed a beat, and on return the drive chain needed just over a turn on the rear spindle screw adjusters. Fuel (at just 85p per gallon!) was used at 42mpg and oil at 330 miles per pint. It wasn’t all good news though. At 2700 miles from new, the top gear pinions failed, necessitating replacement under warranty of the mainshaft, top gear pinion and bearings.

The following year with Suzuki’s attention concentrating on the four-stroke range, the GT500 was quietly dropped. Nowadays, the T500 and GT500’s heritage make it popular for racing with a massive amount of tuning experience available using well-tried techniques.

It also makes a prime candidate as a classic mount, its appeal being its lack of complexity. But do I regard it as appealing as when I was riding big Brit twins in the old days? It’s a completely different world now. The original T500 is worth looking out for, as is the T500II, simply because of their 60s style. But the GT500? Let’s say it makes a great basis for a racer.