When it comes to discussing Honda’s CB400F, the iconic four cylinder sports bike made from 1975 to 1977, the world is divided into two opposed groups. There are those who dismiss the machine as an overrated and gutless aberration that was markedly inferior to its larger siblings.

Others admire it as a daring design that brought multi-cylinder four stroke performance to the middleweight sector. They regard the CB400F as a turning point that tapped a market for riders who wanted the reliability of Japanese machines in a more rakish and sporty package.

I confess to belonging to the latter camp. But the reasons for my allegiance are that, having performance tested the CB400F and machines that preceded and followed it in Honda’s development, it stood out as a ground breaking design that set the tone for other factories to follow.

It was only marginally slower than the CB500 Four launched three years earlier and, more importantly, it steered and handled almost intuitively, a first for Honda, if not the Japanese factories in general. That made the CB400F a prime candidate for production racing, where its potential for tuning and development could be exploited.

Its styling – with a long fuel tank, a sporty seat, a four-into-one exhaust system and a distinguishing graphic simplicity – was ground breaking. But the experience of riding the machine was also completely new. Yes, you had to rev it, but with a six-speed gearbox to play with that was no great inconvenience. Indeed, it added to the fun. And that was the key.

Its styling – with a long fuel tank, a sporty seat, a four-into-one exhaust system and a distinguishing graphic simplicity – was ground breaking. But the experience of riding the machine was also completely new. Yes, you had to rev it, but with a six-speed gearbox to play with that was no great inconvenience. Indeed, it added to the fun. And that was the key.

True, that fun came at a price and it was likely that Honda was hardly making a profit on a retail price of £699 when it was launched in the UK. Or even at £809 in its final model year in 1977.

That’s when the accountants took over again and Honda introduced the five-speed six-valve CB400T twin, a slightly functionally superior machine utterly devoid of personality that was further diluted with the ‘Eurostyled’ CB400N.

Measured by today’s standards, it is easy to criticise the CB400F’s modest performance, weedy brakes and harsh suspension. Even easier to mock a neglected machine’s rotting chrome, iffy ignition and self-destructing camchain tensioner. But once past its prime almost every model of that period had its weaknesses. Especially if it was not serviced by the book.

Break out of the mould

More than a quarter of a century ago, the CB400F was a signal that Honda wanted to break out of the mould, and in more ways than one. Flushed by the world’s response to the four cylinder CB750 in 1969, Japan’s biggest automotive manufacturer launched the CB500 Four in 1971 and the CB350 Four (which never appeared in the UK) a year later.

But after its engineers had exerted themselves on the new fours, Honda began concentrating more on its car range and it is arguable that it wasn’t keeping its eye on the two-wheeled ball, as shown when it replaced the CB250K4 and CB350K4 twins with the awful G5 versions.

They looked tired and were even more tiring to ride. Meanwhile factories like Kawasaki were introducing blockbusters such as the Z1. Honda had to make a dramatic move.

IT was at the Cologne Show in Germany late in 1974 that it happened, and on two fronts. Honda launched the flat-four Gold Wing tourer alongside the ‘Super Sports’ CB400F. Both machines were stunning: the Wing for its immensity (few in Europe really understood that it was the Genesis of the classic US touring machine) and the style of the 400, which was based on the 350 four but with a new chassis, cylinder block, head and gearbox.

With a claimed 37bhp at 8500rpm and a weight of 392 pounds, the CB400F was expected to be the four stroke equivalent of Yamaha’s 350cc two stroke twin: a head-banging scratcher’s delight.

But when in the following February I collected the Honda test bike from dealer Tippets in Surbiton, south London, my first impressions were anything but.

‘Gushing’ barely describes my comments in the subsequent road test in Motor Cycle, the weekly paper: “With looks that scream ‘racer’ from every sparkling highlight on those distinctive four-into-one exhaust pipes to the scarlet works-styled tank and mini side covers and folding setback footrests, it feels so unarguably right it’s almost unbelievable.

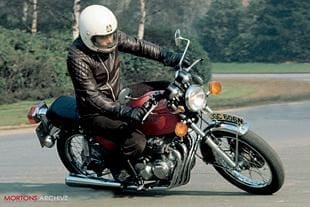

“Smooth as a turbine and quiet as a car, the CB400F offers nimble, secure handling whether in heavy traffic or cruising country roads. It is also very compact and light for a four cylinder machine.”

The CB400F was both a model of refinement – as indeed were the CB350 and CB500 fours. Hardly what a two stroke fiend might find appealing but the revelation was that it steered and handled almost perfectly.

The CB400F was both a model of refinement – as indeed were the CB350 and CB500 fours. Hardly what a two stroke fiend might find appealing but the revelation was that it steered and handled almost perfectly.

Until then Hondas had been afflicted not just by poor suspension but with a propensity to fall into corners, requiring conscious effort from the rider to maintain a line. Many owners would get used to this and regard it as the norm, but to anyone who had the benefit of being able to sample a wide range of models found it annoying. With the compact CB400F it was suddenly like being freed from a shackle.

The performance took a little longer to get used to; about half an hour. We’re accustomed these days to fours that rev to 16,000 or more, but in 1975 a machine that could buzz to 10,000 through the gears demanded a new style of riding.

But I quickly acclimatised to it, and the thrill of winding it up in the knowledge that you wouldn’t rattle the neighbours.

Some say that the CB400F’s performance was a disappointment. I can’t understand why. On a cold February day at MIRA’s 1000-yard test strip, the bike clocked a two-way mean top speed of just over 104mph, only one mph down on the CB500 with a best one-way speed of just over 105mph, revving to more than 10,000 in top gear, way over the red line.

To get consistent top speeds I was flat on the tank and for safety considerations we removed the handlebar mirrors. The idea was to get the best possible speeds from the stock test bike.

Fraction down

Once again to quote the test report: “Its standing quarter time of 14.9secs (with a terminal speed of just over 87mph) was also just a fraction down on the 500. Economy was almost as good as the CB250 with a return of 55mpg at a steady 70; and even when run at 80-85mph, it never consumed any more than a gallon every 51 miles.”

Tuners were quick to exploit the machine’s potential, one of the first being Dixon Racing, the Yoshimura agent based in Surrey. David Dixon offered an over-bored version with a modified cylinder head and special exhaust system.

The stock capacity was taken up from 408cc (51 x 50mm) to 458cc with 54mm diameter pistons and to provide matching breathing capacity the eight valves were polished and contoured and a longer duration camshaft fitted.

At the same time the compression ratio was raised to 10 to 1 and a four-into-one pipe provided better extraction. The stock 20mm-choke Keihin carbs were retained but the main jets upped a size and the needles raised a notch. The standard coil and contact breaker ignition timing was advanced to provide a spark at 40 degrees BTDC.

The chassis was uprated too, with stiffer 85/115lb/inch S&W rear suspension units and front fork internals, and Borrani alloy rims. Gearing was raised a tooth at the gearbox to give 6800rpm at 70mph.

As such, David Dixon’s CB460 was geared about right, as I might have expected from my predecessor at Motor Cycle, a man well versed in the subtleties of getting the best from test bikes at MIRA.

As such, David Dixon’s CB460 was geared about right, as I might have expected from my predecessor at Motor Cycle, a man well versed in the subtleties of getting the best from test bikes at MIRA.

When I tested the bike in March 1976 the top speed was improved to a mean two-way of 107.77mph at 10,500rpm. But acceleration through the quarter mile was cut by almost a second with a time of 14 seconds and a terminal speed of 92.75mph.

By comparison, a stock Honda CB550F I tested at MIRA a week later clocked a mean top speed of 108.8mph with standing quarter mile times of 14.55 seconds and 90.46mph.

At south London dealer Mocheck, boss Ian Tay was so excited by the CB400F that in 1976 he set up a production racing team with three modified machines that he called Faith, Hope and Charity. Backed by Motor Cycle, these were ridden by a number of top stars and many times punched above their weight in the 500cc production class, the Avon Roadrunner series and the TT.

John Ryan, now a sales manager at two Carnell dealerships in south London, was chief mechanic for the Mocheck team. “They were only slightly modified,” he recalls, “but one of the best results was Tony Rutter’s outright win at Silverstone. In the Isle of Man he was clocked at 130mph at Brandish.”

Changes included alloy wheel rims, an elongated fuel tank, racing seat, rearset footrests, clip-on handlebars and a tucked-in and gutted exhaust system.

Extra machine

For the TT, an extra machine was prepared and four riders entered: Phil Carpenter, Alex Ayres, Phil Mellor and Norman Tricoglus. But Tricoglus’s machine suffered a puncture and following confusion in trying to repair it at the pit, the organisers excluded the bike, so Mocheck lost the team prize.

I joined in for a six-hour production race at Cadwell Park with Tricoglus and had a whale of a time diving under bigger machines.

I don’t remember the result, only that we had a huge crash coming back from Louth on the Saturday night that left Norman’s van looking more than a bit twisted. He had to wear a helmet on the way home to Northumberland because the windscreen was missing!

The following year in 1977 Mocheck followed up with a road-going version called the Harrier. This was also based on a 458cc Yoshimura conversion but with a racing camshaft fitted along with a lightened crankshaft and improved porting for the head.

Electronic ignition from Lumenition provided more accurate sparks while a black Piper exhaust system reduced the back pressure. No power figures were quoted but the original 37bhp was likely to have been upped to at least 55bhp.

Electronic ignition from Lumenition provided more accurate sparks while a black Piper exhaust system reduced the back pressure. No power figures were quoted but the original 37bhp was likely to have been upped to at least 55bhp.

As with the Dixon machine, the chassis featured S&W rear shocks but the cast aluminium wheels, fitted with Avon Roadrunner tyres, were from CMA and finished off in white to match the rest of the machine.

At MIRA in December 1977 this was much more potent than the Dixon machine, pulling a mean 113.75 mean top speed with a best one way speed of 121mph. Acceleration was better too with a standing quarter mile time of 13.7 seconds with a terminal speed of 95.47mph.

In this form the CB400F was a real giant killer. But for Honda, it was a cul-de-sac. US riders were unimpressed by the little bike with a big heart and that banged the final nail in its coffin. The CB400F failed to appear in the 1978 model range.

For the full comparative results of the stock 400 v Dixon’s 460 v Mocheck’s Harrier, download the original article.