The sporting sidecar outfit – is any road vehicle other than a fast solo more exhilarating to drive? The fundamental requirements are these: engine capacity should be large and high torque spread over the r.p.m. range. The sidecar should be light, small, smoothly curved and rigidly attached to the machine. For effortless steering, front-fork trail needs to be less than for a solo and to cope with the extra weight, the third wheel should be braked.

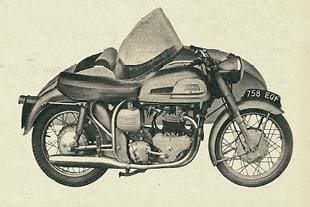

The Norton Dominator 650 Standard with Busmar’s latest open singe-seater, the Dolomite, scores high marks on most of these points. Power is there aplenty – 44 b.h.p. at 6,500 r.p.m. – giving a top speed of about 80 m.p.h. under normal conditions. Acceleration and hill-climbing are decidedly brisk. Handling is delightful and braking powerful.

The mean performance data in the panel do less than justice to the outfit, for when they were recorded a side wind of 25 to 30 m.p.h. was blowing and this cut 3 or 4 m.p.h. off the maximum speed. The high wind also worsened the petrol-consumption figures. When the outfit was driven fairly hard on open roads, it was usual for overall consumption to range from 40 to 45 m.p.g.

Some may argue

Since the engine’s r.p.m. peak is equivalent to 96 m.p.h. in top gear, some may argue that the outfit is overgeared. So beefy is medium-speed torque, however, that there seemed to be no call for lower gearing. On long journeys the engine revelled in keeping the speedometer needle in the 70 to 75 m.p.h. band, and 80 to 85 m.p.h. was always on tap if conditions were reasonably favourable.

A fine indication of the engine’s pulling power is the fact that the outfit was easily restarted on a 1-in-3 test hill. On the level, the Norton would accelerate very rapidly indeed from a walking pace in bottom gear without the clutch being slipped. For tight left-hand corners this sort of throttle response was a boon.

Main-road drags were romped up in top gear and there was no need to make excessive use of the lower ratios to keep up high average speeds. Incidentally, the engine was reasonably smooth right up to its power peak. The gear change was first class. It was commonplace to take the outfit up to 50 m.p.h. in second gear and 70 m.p.h. in third when regaining a high cruising speed after a check.

Main-road drags were romped up in top gear and there was no need to make excessive use of the lower ratios to keep up high average speeds. Incidentally, the engine was reasonably smooth right up to its power peak. The gear change was first class. It was commonplace to take the outfit up to 50 m.p.h. in second gear and 70 m.p.h. in third when regaining a high cruising speed after a check.

Accurate at 30 m.p.h., the speedometer read 1 m.p.h. fast at 40 and 50 m.p.h. As speed increased so did the percentage error; at top speed, flattery was 5 m.p.h.

Use of high revs gave no offence to other road users, for the exhaust, though pleasant and healthy, was reasonably well subdued. Because of reflection from the sidecar body, mechanical clatter could be reduced with advantage. It was found desirable to use super-premium petrol to prevent mild pinking under hard driving.

At the other end of the performance scale, it was quite feasible to burble smoothly along at a speed appreciably below 30 m.p.h. in top gear when blistering acceleration was not wanted.

Provided the relatively steep inclination of the induction tract (20 degrees) was borne in mind, and the carburettor accordingly tickled only sparingly, a first-kickstart from cold could almost be guaranteed. A vigorous thrust on the starter pedal was called for to spin the engine over compression. Once the engine was firing the air lever could be opened without causing spitting back through the carb.

Engaged noiselessly

With the throttle closed, idling was dependable and slow enough for bottom gear to be engaged noiselessly. Slightly heavy to operate, the clutch freed fully and there was no difficulty in selecting neutral from either bottom or second gear whether the outfit was rolling or stationary. The clutch took up the drive smoothly and proved equal to the succession of full-throttle getaways when the performance figures were taken.

Inevitably, access to adjustments on the left side of a machine is impaired by a sidecar. On the Norton this was serious only in the case of the contact-breaker.

Of course, the Norton was fitted with the alternative front-fork yokes that reduce trail for sidecar duty. As a result, the hard work was taken out of cornering without the steering being quite so light as that of some layouts giving even less trail. This meant that while, with a 9-stone passenger, the sidecar could be intentionally lifted on left-hand bends without great exertion, enough effort was needed to ensure that the sidecar was not brought up inadvertently.

A steering damper is fitted but it came in for little use. Half a turn of the wing nut was ample to damp out mild handlebar flutter when the outfit was travelling at low speed on bumpy surfaces.

Suspension of all three wheels was firm and the movement well damped. This kept the outfit on a very steady keel when bumps were negotiated at high speeds.

There was not a scrap of sponginess in any of the brake controls, and the 33ft stopping distance from 30 m.p.h. is extremely good for a sidecar outfit. The sidecar brake is operated by a rod that bears against the underside of the rear-brake pedal. In this way both brakes are applied together.

Characteristics of the rear- and sidecar-brake controls were very well matched. Once the adjustments had been precisely synchronized, stopping power was evenly balanced between the two wheels. Heavy pedal pressure was, however, required.

Characteristics of the rear- and sidecar-brake controls were very well matched. Once the adjustments had been precisely synchronized, stopping power was evenly balanced between the two wheels. Heavy pedal pressure was, however, required.

On the debit side, adjustment of the rear and sidecar brakes is tedious. The scalloped adjuster nut on the rear brake rod is difficult to turn with the fingers, especially as it is tucked so close behind the left-hand silencer. A wing-nut would be an improvement. The cable adjuster for the sidecar brake is screened by the chassis and suspension strut and is impossible to use while the body is on the chassis.

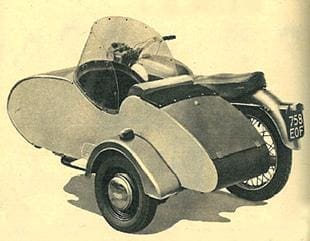

For a semi-sporting sidecar, the Dolomite is roomy and the degree of comfort afforded to the passenger is very reasonable. For long journeys, a footboard would be a worthwhile refinement. Though the seat is shallow enough for use of a cushion to be appreciated, the backrest has a large roll across the top that provides extremely good support for the shoulders.

Swept well back at the sides, the Perspex windscreen provides effective protection from draughts. An outside step in front of the mudguard makes it easy to get in and out – and the fact that the screen is swivelled back on hinges at the rear also helps. In its normal position, the screen is held down by two spring-loaded catches and the joint with the body is effectively sealed by a length of soft rubber.

In good weather the black hood and its framework are neatly stowed in a covered trough behind the seat. Easily and quickly erected, the hood is of double thickness at the edge so as to sandwich the windscreen; the inside of the sidecar remained dry in spite of hours of driving in heavy rain. To prevent interior misting of the screen, there is a ventilator flap in the rear of the hood.

It is not necessary to disturb the passenger to gain access to the roomy rear luggage compartment; there is an external lid which can be locked. View original article