The LE Velocette was such an oddball that it’s a sitting target for criticism. It weighed and cost more than half as much again as a contemporary BSA Bantam, but didn’t go much faster. Its complicated engine relied on old-fashioned side valves, and it appeared to have been styled by the Semi-Mobile Box Co. It didn’t even sound like a proper motorbike for heaven’s sake!

And yet this was a machine that stayed in production for 20 years. Its engine had the same layout as the prestigious BMW, and it successfully introduced in-built weather protection even before it was common on scooters. Perhaps most remarkably, the LE (and its derivatives) evoke enough fervour to justify a dedicated owners’ club outside the mainstream Velocette one.

But we have to remember that this was not one of those concept bikes from a post-WWII entrepreneur. It was mass-produced by a company that had been successfully making motorcycles for decades, surviving when other firms had either been stillborn, or fallen by the wayside. So it’s much too simplistic to suppose that Velocette’s directors didn’t know what they were doing, or were chasing an impossible dream.

But we have to remember that this was not one of those concept bikes from a post-WWII entrepreneur. It was mass-produced by a company that had been successfully making motorcycles for decades, surviving when other firms had either been stillborn, or fallen by the wayside. So it’s much too simplistic to suppose that Velocette’s directors didn’t know what they were doing, or were chasing an impossible dream.

Clubroom pundits may suggest that the Hall Green firm should have continued to concentrate on its sporting singles after the war, but they knew very well that it was impossible to make affordable cammy roadsters. However, Velocette did have the good business sense to keep the old MAC in production, and they introduced the new MSS in 1954, eventually developing it into the charismatic Thruxton Venom that kept things afloat until 1970.

The real question, then, is not why Velocette diversified into ride-to-work bikes, but why they thought that the transport-hungry post-War market needed a sophisticated luxury commuter, when other manufacturers were content to simply bolt a Villiers power unit into a basic frame.

The main factor surely must be that nobody in the 1930s and 40s foresaw a time when ordinary working-class people could afford a car. It followed that if folk wanted to be mobile they would buy a motorbike, and while most would opt for the simplest and cheapest, some would always aim a little higher. And that implied an exploitable sales opportunity, because Veloce Ltd had always been associated with the quality end of the market.

Even early two-stroke Velocettes – produced by founder John Goodman (neé Gutgemann) – were always just that bit faster and better finished than most of the opposition, and when Percy and Eugene Goodman succeeded their father in 1928, they subscribed to the same general philosophy. They went about it in different ways, though, with Percy’s interest in racing resulting in the K-series cammy singles, an early example of which future Technical Director Harold Willis rode into second place in the 1928 Junior TT. Eugene was more down to earth, and – with the support of designer Charles Udall – he developed the M-series high camshaft ohv singles that were easier and cheaper to build.

Even early two-stroke Velocettes – produced by founder John Goodman (neé Gutgemann) – were always just that bit faster and better finished than most of the opposition, and when Percy and Eugene Goodman succeeded their father in 1928, they subscribed to the same general philosophy. They went about it in different ways, though, with Percy’s interest in racing resulting in the K-series cammy singles, an early example of which future Technical Director Harold Willis rode into second place in the 1928 Junior TT. Eugene was more down to earth, and – with the support of designer Charles Udall – he developed the M-series high camshaft ohv singles that were easier and cheaper to build.

Naturally, then, Eugene was the brother who had the vision of a quality motorcycle for ‘everyman’, and even before WWII he had purchased a large sheet metal press to mass-produce bodywork. He envisaged a production rate of 300 per week, and if that had been achieved, the resultant economies of scale might just have hoisted Velocette into the big time.

It never happened, which isn’t surprising knowing the track record of ‘motorcycles for everyman’, even with a top man on the job. Phil Irving – better known for his work on Phil Vincent’s big twins – had re-joined Velocette in 1936 (having been a draughtsman there when he first came to Britain) and he initially worked on exotica that included the fabled ‘Roarer’. During the War, however – with motorcycle development temporarily suspended – he did general engineering until he was injured by an incendiary bomb. Legend has it that while he was recuperating, he laid out the basic design of the civilised machine that matched criteria discussed by himself, Eugene Goodman and Charles Udall.

What the legend conceals is that very little of Irving’s design was actually incorporated into the production LE. His sketches showed a shallow V-twin in a rigid frame with chain rear drive. It was Charles Udall – coincidentally also working while on sick leave so as not to disrupt the war effort – who transformed the design into the definitive LE with its flat-twin engine, shaft drive and full suspension. Prototypes were made with the help of trade contacts, and it was on the working drawings that the letters ‘LE’ were first used as an abbreviation for Little (or just possibly, Light) Engine.

What the legend conceals is that very little of Irving’s design was actually incorporated into the production LE. His sketches showed a shallow V-twin in a rigid frame with chain rear drive. It was Charles Udall – coincidentally also working while on sick leave so as not to disrupt the war effort – who transformed the design into the definitive LE with its flat-twin engine, shaft drive and full suspension. Prototypes were made with the help of trade contacts, and it was on the working drawings that the letters ‘LE’ were first used as an abbreviation for Little (or just possibly, Light) Engine.

A flat twin was essential because Eugene Goodman felt that only a total absence of vibration would persuade women (and men who couldn’t afford a car) to take to two wheels. Everything else flowed from trying to appeal to this particular market sector. The engine had to be a four-stroke, to avoid the uneven running and odd lubrication requirements of strokers, and it was a side valve to minimise width and noise. Water-cooling further quietened the motor and stopped it overheating, and hand starting and gear changing were specified to safeguard fashionable shoes.

Of course, much of this was overkill, as the well-made Velocette singles with their narrow crankcases already produced less vibration and mechanical noise than anything else on the market. And ironically, every single aspect was to backfire in one way or another.

Of course, much of this was overkill, as the well-made Velocette singles with their narrow crankcases already produced less vibration and mechanical noise than anything else on the market. And ironically, every single aspect was to backfire in one way or another.

Everybody knew the virtues of BMW-style flat twins, and that would have been good news except that the same association also suggested complication and unaffordable prices. The LE’s specification even outdid BMW’s in respect of its water-cooling, but ironically that was too good. On the short commuting trips for which the LE was ideal, the engine never got hot enough to boil off condensation, so the oil deteriorated into a damaging sludge.

Early LEs only had three-speed 150cc engines, and that, coupled to the inherent inefficiency of side valves meant that even their target customers found them underpowered. In any case, non-motorcyclists proved predictably resistant to the idea of getting onto a two-wheeler – whatever its specification – and a more typical buyer was an older motorcyclist who’d grown out of the desire to be faster and noisier than his mates.

Naturally, existing motorcyclists didn’t like the hand start and gear change, and so they were ditched in 1958, when the gearbox also gained a fourth ratio. By that time the engine had been stretched to nearly 200cc, and the lubrication problems, and other niggles, had been ironed out. The result was designated the MkIII; it was still boxy and relatively slow, but it was largely problem-free and found its definitive niche in the hands of countless police patrolmen.

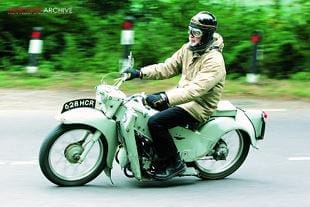

The mature civilian motorcyclists hadn’t entirely disappeared, though, and some LEs – like the totally authentic version I’m testing today – were still bought and appreciated. Edward Bristowe purchased this one from Alec Bennett’s in Southampton in June 1964, and used it for much more than local commuting. For instance, he and his wife went on honeymoon on it (hopefully with some padding on the carrier pan!) and by the time he laid it up he’d covered the best part of 30,000 miles.

The mature civilian motorcyclists hadn’t entirely disappeared, though, and some LEs – like the totally authentic version I’m testing today – were still bought and appreciated. Edward Bristowe purchased this one from Alec Bennett’s in Southampton in June 1964, and used it for much more than local commuting. For instance, he and his wife went on honeymoon on it (hopefully with some padding on the carrier pan!) and by the time he laid it up he’d covered the best part of 30,000 miles.

In 1985 he brought it out of retirement, had it MoT’d and went to tax it, only to find that because he’d missed the deadline for telling Swansea’s computer of its existence, he’d have to accept a new age-related registration. Sadly, it seems that Mr Bristowe was then taken ill, and never actually used his LE again. Eventually he and his wife advertised it in the owners’ club magazine – the cleverly named On The Level – and it was snapped up by Hampshire flat-twin enthusiast Roger Holyoake, whose Velocette Valiant was featured by TCM in February 2002.

It was a non-runner, but appeared in good nick apart from some water leaks. One of the cylinder heads became damaged as it was removed, so it had to be replaced, but apart from that, Roger has only replaced the clutch cable and the rectifier, and sorted out a perished cable and grommet that were causing misfiring. Even the tyres – at least 20 years old – are free of surface crazing; a testimony to careful storage in a dark shed. Roger’s friend and fellow flat-twin fan, Ian Munro – whose bikes we’ve also featured on occasion – helped with the work and fitted the oil pressure gauge (a £2-19s-6d option when new).

The LE came with old and new logbooks and quite a lot of documentation, and it also had its old number plate under the age-related one. Fortunately, the licensing authorities are now more understanding, so Roger had no trouble getting the old registration reinstated. And if you are wondering why a machine first registered in 1964 has no ‘B’ suffix, it seems that Southampton’s Vehicle Record Office initially chose to simply ignore the new system of additional registration letters.

I’ve never ridden an LE, but I’ve heard all the jibes about it being an ‘expensive way of going slowly’, so I wasn’t expecting it to be a ball of fire. Well, it’s not, but it’s nowhere near as staid as hearsay would have you believe. The engine’s side valves give it more torque than you’d expect with such modest horsepower, and when you couple that with a willingness to rev, and well-chosen gear ratios, you end up with a bike that can more than hold its own on club runs. The urban speed limit can be speedily reached in second, and hanging on to third until the speedo reads 40mph (the instructions under the toolbox lid imply that 44mph equates to maximum revs) gets you up to decent cruising speeds surprisingly quickly. And it’s all done with minimal mechanical and exhaust noise, totally justifying contemporary advertisements calling this the ‘siLEnt’ Velocette.

I’ve never ridden an LE, but I’ve heard all the jibes about it being an ‘expensive way of going slowly’, so I wasn’t expecting it to be a ball of fire. Well, it’s not, but it’s nowhere near as staid as hearsay would have you believe. The engine’s side valves give it more torque than you’d expect with such modest horsepower, and when you couple that with a willingness to rev, and well-chosen gear ratios, you end up with a bike that can more than hold its own on club runs. The urban speed limit can be speedily reached in second, and hanging on to third until the speedo reads 40mph (the instructions under the toolbox lid imply that 44mph equates to maximum revs) gets you up to decent cruising speeds surprisingly quickly. And it’s all done with minimal mechanical and exhaust noise, totally justifying contemporary advertisements calling this the ‘siLEnt’ Velocette.

Unlike some small capacity motorcycles, the LE has handling good enough to encourage you to use all of the performance. And, apart from having a rather cramped riding position (not helped by the gear-change lever obstructing half of the footboard) it’s also very comfortable. It was, after all, the first mass-produced Velocette to feature the famous patented ‘Arcuate’ system for varying the rear suspension’s effective spring rate and damping. Despite its modest capacity, the LE could never be honestly be described as a lightweight, which probably helps stability, but means that the modestly sized brakes have to work quite hard to keep you out of trouble.

Weather protection is a large part of the LE’s intended appeal, and this one had a genuine ‘Olicana’ screen (a £5-19s-6d option) that Roger has removed because: “The bike’s slow enough already, I dread to think what it would be like trying to push that sail through a headwind.” The screen is astonishingly old-fashioned for the mid-1960s, and a single-curvature Perspex section tops off hand protection in a fragile celluloid-type material, which in turn has an apron made from genuine cowhide!

Weather protection is a large part of the LE’s intended appeal, and this one had a genuine ‘Olicana’ screen (a £5-19s-6d option) that Roger has removed because: “The bike’s slow enough already, I dread to think what it would be like trying to push that sail through a headwind.” The screen is astonishingly old-fashioned for the mid-1960s, and a single-curvature Perspex section tops off hand protection in a fragile celluloid-type material, which in turn has an apron made from genuine cowhide!

But it is in keeping with the rest of the machine, and a streamlined screen would look wrong unless the legshields and bodywork were also made more curvaceous. Not easy with pressed steel, but a doddle with glass fibre mouldings, and in the early-1960s, the Goodmans – still pursuing their holy grail – called in Avon Fairing supremo, the late Doug Mitchenall.

“I should known it was hopeless,” Doug subsequently told me, “but it seemed a good idea when I sketched out the basics of what became the Vogue on a napkin after a few drinks at dinner. Unfortunately, by the time Velocette had made a new frame as well, that poor little engine was more overwhelmed than ever.”

So the Little Engine that gave the LE its name was ultimately its downfall… or was it? It’s as easy to think of improvements to the LE as it is to make fun of it. But just think, enlarge the engine and you’ll need bigger brakes and chassis, and straightaway you’ve got an even heavier and more expensive machine that will please nobody, not even the Police.

The LE was undoubtedly a bit of an oddity, but the fact remains that as it left the factory it provided a well-balanced package of performance, handling and weather protection. Eugene Goodman may have failed to produce the motorcycle for Everyman, but he came as close as anybody ever has.