It can be positively stated that no other racing rider has ever put more effort into his grand prix career than four-times sidecar world champion Eric Oliver.

Although he gained factory support from Norton and Watsonian sidecars, Eric was essentially a privateer. There was never any question of his being ‘his own boss’, unrestricted by Norton’s (AMC Ltd) opposition to streamlining and other innovations which helped him to win his four world titles between 1949-54.

Eric had no secret formula for achieving success. Apart from obtaining the best possible equipment – always Norton and Watsonian – it was simply that he was totally dedicated and thorough in every aspect of preparation, both mechanical and mental. For example, even after years of experience, he regularly practised his starting technique to save a split second.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

Indeed, despite 18 grand prix victories which gained him four world titles, Eric was rarely satisfied. When he lost a race or made a mistake, he wanted to know why he had gone wrong. He did not make excuses or blame others. Whatever the problem, he corrected it.

Eric’s formula to maintain his racing weight of 11 stone was simply to give up eating until the excess poundage disappeared. “I stopped eating for a few days whenever my leathers felt tight,” he once told me.

Oblivious to age, Eric was 43 in 1954 when he won his final world title. Nor was it advancing years that persuaded him to quit. That came only when a single cylinder Norton could no longer beat a BMW twin.

Born in 1911, Eric came from Crowborough, Sussex, and began grass track racing in 1929/30. Still living in Crowborough and now in his Nineties, Eric’s elder brother Ben vividly recalls Eric’s exploits. “He was 18 or 19 when he started racing on all the local grass tracks. He had solo machines and I remember he did very well on a 499 Rudge.

“He got a 500 Excelsior-JAP (B14), but it didn’t handle too well and he put a sidecar on it and started winning on that,” added Ben.

Retirements also removed him from the 350 and 500cc Junior and Senior races on Nortons in 1938, but 17th place in both races were his results on Nortons in 1939.

Motor engineer

An apprenticed motor engineer, Eric flew as a flight engineer in Lancaster bombers during the Second World War. “He went on more than 40 raids,” said brother Ben, proudly. I first saw Eric Oliver racing at Brands Hatch in 1946 where, always with the racing number 13, he raced 350/500cc solos and a 596cc Norton sidecar.

His 350/500cc rides were unique in that Eric had only one machine and the JAP engines were changed between races by mechanics while Eric raced his sidecar. The swap-over took about ten minutes and was needed four times during most meetings, involving heats and finals.

I came close to buying that machine at the end of 1947 (with only the 350 engine). Eric wanted a 500 Matchless for moto cross to supplement his racing income when he joined the Continental Circus with his 596 Norton outfit in 1958. (We didn’t do a deal. Eric was not impressed with my 350 bike.)

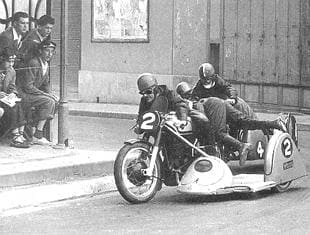

After successfully acquainting himself with the ‘circus’ in 1948, initially with passenger Les Nutt and then Denis Jenkinson, Eric subsequently devoted himself to sidecar racing – although he did ride solo in the 1947/48/49 TTs and he had a brand new, works-supported NortonWatsonian outfit for 1949.

This was a ‘Garden Gate’ model with a girder front fork, 21″ front wheel and a 596cc ‘double-knocker’ engine.

Just three of the FIM classics catered for sidecars in 1949. Belgium, Switzerland and Italy – and Eric, with ‘Jenks’ in the chair, won all three from Ercole Frigerio on a 600cc four cylinder Gilera-Rondine converted from a pre-war supercharged machine.

An end-of-season adventure saw Eric in company with Artie Bell and Geoff Duke at the banked Montlhery circuit near Paris, netting a bag of world records. A disappointment for Eric was not to take the world’s one-hour sidecar record over 100mph for the first time.

Replacement tyre

After averaging 101mph for 47 minutes, the rear tyre of his 596 Norton gave out. The replacement tyre lasted a little longer, 50 minutes. With a third tyre fitted, Eric was forced to slow down and stay just ahead of the existing 92mph record. The tyre held and Eric took the record at 95mph, later raising it to 97mph in 1950.

Still with ‘Jenks’ occupying the Watsonian side attachment, Eric again dominated the same three-race season in 1950 with Frigerio in pursuit.

The FIM lowered the sidecar class engine capacity to 500cc in 1951 and it was reckoned that Gilera had influenced this decision when Frigerio appeared on one of the new post-war four cylinder machines.

Oliver also appeared on a new outfit, a ‘Featherbed’ model with rear suspension and telescopic front fork.

Denis Jenkinson had moved on and the Watsonian chair was occupied by Italian Lorenzo Dobelli. Their dynamic cornering kept them ahead in the world title chase, but Frigerio beat him across the line to win the Italian GP at Monza by just 0.4 of a second.

Dobelli. Their dynamic cornering kept them ahead in the world title chase, but Frigerio beat him across the line to win the Italian GP at Monza by just 0.4 of a second.

Eric’s progress during 1952 was interrupted in May by an excursion into straw bales at a minor meeting in Bordeaux where both he and Dobelli each broke a leg. This caused them to miss the Swiss GP at Berne won by Albino Milani (Gilera 4) from Cyril Smith on a private Norton.

Frigerio had made a poor start but quickly caught the leaders record- breaking speed. Then he ran wide at Tenni Corner and into some trees which lined the road. He was killed instantly.

Determined to defend his world title, Oliver reappeared in the Belgian GP in early July with his leg still encased in plaster. Amazingly he convinced officials that he was still capable of racing but Dobelli still on crutches, was refuse and his place taken by an extremely brave Belgian.

Norton had not expected Eric to start and boss Joe Craig, impressed by Cyril Smith’s performance in Switzerland, had given him a works engine. Even so, no-one seriously expected the singles to stay with the fours of Milani and Ernesto Merlo, Frigererio’s replacement.

Gileras close behind

Far from it! Oliver led from the start with Smith next and the two Gileras close behind. Power and acceleration took Milani ahead while slipstreaming and sheer skill kept Oliver in the hunt. The lead changed constantly until the final lap when Milani gained what usually would have been a winning lead – but for the phenomenal riding ability of Oliver.

He gained most of the lost ground with a meteoric arrival at La Source hairpin which put him on Milani’s tail. Eric judged his move perfectly to nip ahead for another split-second victory.

Two weeks later at the German GP at Solitude the outcome was quite different. Dobelli was back and Oliver had fitted his outfit with 16-inch wheels.

No longer in plaster, Eric led Milani from the start with Smith and Merlo next. Milani rolled over and out of the race, and Merlo got ahead of Smith, but Oliver appeared to be safe until the axle mounting of his sidecar wheel snapped and put him out.

Meanwhile, Smith caught Merlo napping and slipped ahead to win by 2.2 seconds.

This victory, with second place to Merlo at Monza, helped Smith to win the 1952 world title.

Oliver did not feature at Monza but ended the season with a win in Spain, where Smith was slowed by a broken frame and Merlo retired with misfiring. Oliver was fifth in the world placings.

Considerable change occurred in 1953. Gilera withdrew their sidecar support and BMW began to appear with Wiggerl Kraus and Wilhelm Noll as the factory entries.

The Belgian GP opened the sidecar season and at that first encounter the Be-Em opposition was no match for Oliver and Smith, Stan Dibben and Les Nutt their respective passengers.

However, despite their shared support from Norton, Oliver and Smith were not team-mates. They finished at record speed, less than one second apart – 76 seconds ahead of Kraus. Noll was sixth.

Twelve outfits contested the French GP at Rouen. The factory BMWs were absent and the win went easily to Oliver by more than a minute from Smith.

Only seven outfits appeared at the Ulster GP where the two leading Brits gave a thrilling demonstration until Oliver’s engine seized a couple of miles from the fmish.

The factory BMWs reappeared at the Swiss GP. In this race Eric stormed away from Smith and Noll to win by 29 seconds and smash Frigerio’s lap record by 4.4 seconds.

Only the Italian GP remained and yet again Oliver and Smith were as one for 16 laps (62.6 miles) around the Monza Autodrome. They finished just one tenth of a second apart – but with Oliver in front. An interesting aside was that Oliver lent his experimental streamliner to Frenchman Jacques Drion who finished third.

Highlight of the 1954 season was the return of a sidecar race to the Isle of Man TT, the first since 1925. However, there was no advantage for Oliver. He had raced solos around the TT course, but the sidecar race was to be over the 11-mile Clypse circuit.

Les Nutt resumed as Oliver’s passenger after Stan Dibben joined Cyril Smith, his future father-in-law.

No doubt inspired by the Manx atmosphere and aboard an improved version of the streamliner, which Les Nutt helped to build at Watsonians, Eric powered home ahead of three BMWs piloted by Fritz Hillebrand, Wilhelm and Walter Schneider. Smith retired. Eric scored again in Ulster with Smith next, pursued by Noll, Hillebrand and Schneider.

There was no question that the works Norton engines then raced by Oliver and Smith were better than the best from BMW, for Oliver astounded by beating Noll by 44.8 seconds in another record-breaking Belgian GP.

An arm injury sustained at a minor meeting ruined the remainder of Oliver’s GP season, for although he returned for the Swiss and Italian races, he unaccountably failed to feature and Noll took the world title. Stan Dibben recently told me that Eric was more seriously injured than he revealed. “I think he hurt his back and could hardly move. But that was Eric,” said Stan, “he never gave up.”

Norton withdrew works support after 1954, but both Oliver and Smith continued with the factory’s short-stroke, outside-flywheel engines in 1955. But BMW were providing full support and it soon showed.

Both Oliver and Smith retired from the TT, won by Schneider. Faust took the Spanish GP ahead of Smith and Oliver and was first again in Germany and Holland – where Smith gained fastest lap before retiring.

By then, Eric Oliver realised the glory days were over for Norton and he retired from GP racing to open a motorcycle shop in Staines. He never lost interest or enthusiasm. For a while he raced a Lotus sports car, but motorcycles were his first love and he returned to the TT in 1958 with a standard 500cc Dominator twin fitted with a Watsonian Monaco sidecar and an intrepid lady passenger, Pat Wise. They finished 10th at 59.95 mph.

The ACU restored the 125 and 250cc races to the Mountain course in 1960 but had initial doubts about a sidecar race over the full circuit.

Oliver and Stan Dibben had ridden over the Mountain ahead of the roads-opening car after the Senior TT in 1959. Few may have noticed, for the weather was atrocious. Nevertheless, the ACU was satisfied and a race was set for 1960.

As an MCN reporter, I phoned Eric for his comment and his instant response was that he would enter the race. He also said “Let’s go over and have a look around.”

So I spent New Year’s Day in 1960 hurtling around the TT Course with Eric Oliver. Needless to say, that was an adventure. Anyway, Eric declared he would race and firmly reckoned that his knowledge of the 37.73 mile course would give him a good chance of success.

What might have been never happened. With Stan Dibben in the chair and supremely confident, they crashed during practice when the front fork of Oliver’s machine snapped off at the steering head.as they thundered over the Mountain. Fortunately, neither Eric or Stan was seriously injured, but neither of them chanced to race again.

But Stan reminded me that is not quite true. “We raced in a classic meeting at Brands Hatch in 1978. Eric had got a Garden Gate outfit with the engine on dope. It was a flier and we lapped within a second of our best time in 1953.

“I remember Eric saying to me, Are you sure you want to do this? I’ve had a couple of heart attacks, you know.’ We re-lived 1953 that day,” said Stan.

Sadly, Eric Oliver suffered a stroke from which he died in 1979 and a unique motorcycling chapter was closed. He was then aged 68. View original article