There’s a subtle irony in the fact that the Triking, a sporty little Morgan-like three-wheeler currently built in Norfolk should utilise the power unit and transmission of the transverse vee-twin Moto Guzzi motor cycle; because in truth that engine – or, more correctly, the progenitor of that engine – had been designed for use in a three-wheeler anyway, and its subsequent installation in a motor cycle frame was something of an afterthought.

It all started when the Italian Army approached the Moto Guzzi factory with a request for a cross-country three-wheeler capable of coping with extraordinary terrain. The design work was handed to Giulio Carcano, who had been responsible for the Moto Giuzzi racers in the heyday of Italy’s road racing dominance.

Major design

Indeed, it was to be Carcano’s final major design exercise under the Moto Guzzi banner before he resigned from the company in 1963, bored with the everyday tedium of utility roadster design.

Carcano envisaged a transverse veetwin air-cooled engine with a direct-coupled transmission unit, and in the early stages of the project he gained a great deal of amusement from installing a prototype in the chassis of a Fiat 500 car. There was, of course, an underlying serious side to the experiment, and the lessons learned were absorbed in the actual three-wheeler which was to follow.

Carcano envisaged a transverse veetwin air-cooled engine with a direct-coupled transmission unit, and in the early stages of the project he gained a great deal of amusement from installing a prototype in the chassis of a Fiat 500 car. There was, of course, an underlying serious side to the experiment, and the lessons learned were absorbed in the actual three-wheeler which was to follow.

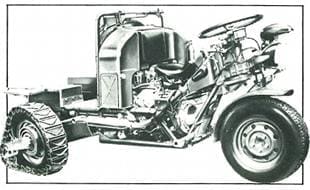

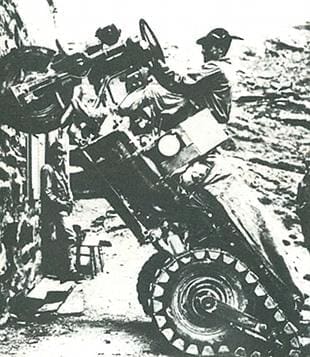

Labelled 11 Mulo Meccanico (The Mechanical Mule) the military tricycle had the unusual feature of shaft drive to all three wheels. For still more traction on tricky or boggy going, behind each rear wheel was a smaller skeleton wheel which, when required, could be lowered to ground level. In normal use, the two main rear wheels ran on rubber tyres, but for cross-country work a caterpillar track could be fitted over the main and auxiliary rear wheels.

Between 1960 and 1963, approximately 200 Mechanical Mules were built and supplied to the Italian Army’s Alpine regiment for use in mountainous territory. Engine capacity was 745cc (80 x 75mm bore and stroke), but because torque rather than performance was the aim, power output was a modest 20 bhp at 4,000 rpm.

By mounting the vee-twin engine and transmission train transversely, with the line of the crankshaft at an angle to the horizontal, the drive could be transmitted fore and aft with minimal loss of power. Though the cylinders were air cooled they were partly shrouded by the steelwork of the vehicle’s body and it was necessary to arrange for a blast of air to be directed over the fins, by means of a centrifugal fan at the front of the engine shaft, drawing air through a forward-extended filter and delivering it through sheet-metal ducts.

Six forward speeds

Six forward speeds

Built in unit with the engine was a gearbox affording no fewer than six forward speeds plus reverse! It embodied a torque-dividing differential, to supply power in the proportions of one-fifth to the front wheel, and four-fifths to the rear wheels. From the gearbox, one propellor shaft ran forward, between the vee of the cylinders, to a bevel box at the base of the steering head, then downward by a shaft housed in the (slightly) telescopic fork leg to a spiral bevel and crown wheel on the front wheel spindle.

There was no rear axle as such and, instead, a cross-shaft and bevels behind the gearbox took the drive to each wheel through individual propeller shafts housed within the wheel arms.

The gear lever was operated by the driver’s right hand, and a safety catch on the lever prevented accidental engagement of first, second, or reverse gears. The steering wheel was offset to the left of the steering column, which it drove through reduction gearing.

Engine flywheel

A Magnetti-Marelli starter motor mounted on the left of the crankcase engaged with the toothed rim of the engine flywheel. The driver sat on a saddle of tractor type, with a backrest formed in a recess of the 11.75 gallon fuel tank which ran across the whole width of the truck. Fuel from the tank was delivered by a Weber PM15 diaphragm-type pump on the right-hand side of the crankcase, to a single Weber 261MP carburettor fitted with a substantial military-type air filter.

Dry-sump lubrication was incorporated, with the oil tank built into the front section of the Mule’s frame.

Pressed-steel wheels were designed to take wide-section low-pressure tyres. Lowering of the auxiliary rear idler wheel was carried out by mechanism from the rear differential, and could be completed on the move over a distance of 27 yards. A calibrated tripper joint was fitted, to prevent excessive strain on this assembly. Brakes were a mixture of hydraulic and mechanically operated drum type, the right foot applying the rear wheel brakes hydraulically while the right hand applied the front brake mechanically; in addition, and also operated by the right hand, a parking brake lever acted on the rear shoes by mechanical linkage.

Pressed-steel wheels were designed to take wide-section low-pressure tyres. Lowering of the auxiliary rear idler wheel was carried out by mechanism from the rear differential, and could be completed on the move over a distance of 27 yards. A calibrated tripper joint was fitted, to prevent excessive strain on this assembly. Brakes were a mixture of hydraulic and mechanically operated drum type, the right foot applying the rear wheel brakes hydraulically while the right hand applied the front brake mechanically; in addition, and also operated by the right hand, a parking brake lever acted on the rear shoes by mechanical linkage.

11 Mulo Meccanico was designed to be used virtually anywhere, in the worst possible weather conditions, and so that it could ascend extremely steep slopes a sprag was incorporated to prevent the machine from sliding backwards. The fuel tank was provided with a pressure cap, to avoid spillage in abnormal conditions; the tank also embodied lockers for the tool kit and battery, and a quick-action plug to permit rapid drainage, while a spare wheel and tyre was carried on its rearward face.

Electrics were 12-volt and were provided by a 180-watt Marelli dc dynamo, and the lighting equipment was completely duplicated, for normal or blackout situations, both standard and shielded lights being mounted front and rear—though by present-day standards a 35/35-watt main bulb would seem a little dim. The dash panel embodied an oil pressure warning light, illuminated ammeter, fuse box, socket for portable handlamp, and a further socket for an auxiliary battery. All bearings and electrical connections were watertight, and the wiring harness was radio suppressed.

A combination of tubing and steel fabrication was employed in the robust chassis, and all-up weight including lubricant, full fuel tank, tools, spare wheel, and caterpillar tracks worked out at 2,205 lb; excluding the driver, the possible payload. was a further 1,102 lb.

Fully laden, the Mule could reach a top speed of 31 mph on a well-surfaced road. Average fuel consumption was 18.6 mpg which, with the 11.75 gallon tank, afforded a range of 217.5 miles on good roads in hilly country, or nine hours when driven across open countryside.

Giulio Carcano’s departure from the Moto Guzzi design office—to devote his time to speedboats and similar more-exciting projects—left a void which was not filled until the arrival in 1967 of Lino Tonti, who will be remembered for his work with Bianchi and, of course, for his own Linto and Paton racing models.

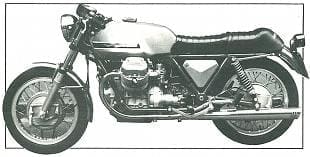

At this time Moto Guzzi had been asked to design a large-capacity motor cycle for police patrol work. There was no suitable engine in the company’s existing motor cycle range, and as a matter of expediency Tonti resurrected the transverse vee-twin that had powered the Mechanical Mule.

At this time Moto Guzzi had been asked to design a large-capacity motor cycle for police patrol work. There was no suitable engine in the company’s existing motor cycle range, and as a matter of expediency Tonti resurrected the transverse vee-twin that had powered the Mechanical Mule.

This was rejigged to fit a motor cycle frame, power characteristics were adapted to suit the new purpose, and a more suitable gearbox was designed. The result was the soon-to-be-famous Moto Guzzi V7, sold for police work all over the world and from which, in due course, the present range of transverse vee-twin Moto Guzzi models would be derived. All the later development was the work of Lino Tonti who, as Chief Engineer, continues to be in charge of Moto Guzzi design today.