To Honda’s top brass it must have, at first, sounded like the craziest of ideas. Not only a six-cylinder motorcycle with the pots inline across the frame, but also one of more than 1000cc. It could be huge and unwieldy, more so than Benelli’s 750 Sei.

But, with fabled engineer Shoichiro Irimajiri at the helm of Honda’s Research & Development department, the concept of a six-cylinder sports bike stood a stronger chance of success. He’d been part of the team that designed the six-cylinder 250cc and 297cc machines raced in the 1960s to world Grand Prix championships by Mike Hailwood and Jim Redman.

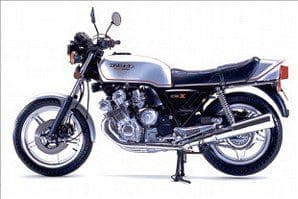

And so the CBX was developed for a launch at the end of 1977 to a shocked motorcycle world that couldn’t believe a six-cylinder machine could look and sound so fantastic and handle as well as it did. It was a master stroke, and the first of a number of madcap motorcycles launched by Honda, which wanted not just to produce excellent products, but had the chutzpah to explore the extraordinary, such as the CX500 Turbo V-twin and, with oval-piston technology, the NR500 racer and NR750 sports bike. That the CBX had only a brief model run between 1978 and 1982 is neither here nor there, it had the desired effect of flooring the opposition and establishing Honda as an engineering master.

Neither is the CBX a forgotten fancy some three decades on. The sound and fury of six-cylinder motorcycling is continued by owners around the world who have modernised and restyled their machines in ways that its original designers could never have imagined. No modern motorcycle has the same riveting effect of so much blatant and shameless complexity.

Neither is the CBX a forgotten fancy some three decades on. The sound and fury of six-cylinder motorcycling is continued by owners around the world who have modernised and restyled their machines in ways that its original designers could never have imagined. No modern motorcycle has the same riveting effect of so much blatant and shameless complexity.

Imagine then the impact when we were told that Honda would be launching a six-cylinder sports bike. Three weeks before Christmas 1977, at an evening press presentation during the launch of the V-twin CX500 Honda at Nogaro in France, R&D chief Irimajiri handed out small photographs of the prototype CBX along with a brief specification. We were gob-smacked, even more so because soon after we were invited to ride the bike at its international press launch in Japan. The story of the CBX’s early development had been shrouded for many years. However, Mel Watkins, a leading authority on the machine and former president of the CBX Owners’ Club in the UK, has used his contacts in Japan to piece together the series of events that led to the launch, of what was then, the most powerful production motorcycle ever offered for public sale.

‘At that point it was decided by Irimajiri that the six, with its more pleasing high-revving exhaust sound, had more potential than the four’

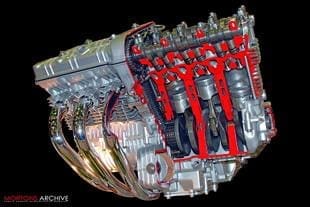

In the spring of 1976, Irimajiri created a project team to develop two motorcycle engines, one with four-cylinders the other with six, but both with double-overhead camshafts and four valves per cylinder; the arrangement used on the racing machines in the 1960s that offered more potential for power than the single-overhead-cam two-valve set up used until then on Honda’s four-cylinder road bikes. It was about this time that Honda revived its racing programme with special 1000cc machines developed for endurance events in Europe. These were based on the CB750 Four and featured dohc 16-valve heads and gear drives rather than chains.The new four- and six-cylinder engines for road use would, however, have chain drives, as was specified, with development running side-by-side for six months. At that point it was decided by Irimajiri that the six, with its more pleasing high-revving exhaust sound, had more potential than the four.

By now called Project 422, the project was led by Shunji Tanaka, with engine design by Masahuri Tsuboi and the styling by Minoru Morioka. An early mock-up of the six shows that various parts were used from a number of models, but what is interesting is that this was based on CB750 crankcases, with the cylinder block and head welded up from CB750 components, and topped by dummy camshaft covers and drive. The design team viewed this monster of an engine and concluded that it was ‘impossible’ to make work – but they did it.

By now called Project 422, the project was led by Shunji Tanaka, with engine design by Masahuri Tsuboi and the styling by Minoru Morioka. An early mock-up of the six shows that various parts were used from a number of models, but what is interesting is that this was based on CB750 crankcases, with the cylinder block and head welded up from CB750 components, and topped by dummy camshaft covers and drive. The design team viewed this monster of an engine and concluded that it was ‘impossible’ to make work – but they did it.

Work concentrated on getting the best riding position around the massive engine.

The engine design was finalised using a layout similar to those found on the Grand Prix racers. To keep the engine as narrow as possible, the alternator and ignition units were located behind the crankshaft above the gearbox. A number of styling ideas were tried before creating full-size clay models. One was inspired by fighter aircraft design, but once it was seen in three dimensions it was clear that the frame would be weak. The inlet porting was also a bifurcated version with three carburettors that limited power.

Development of the CBX

In 1990 Shoichiro Irimajiri described the development of the CBX in a letter to Mike Brown of the US CBX owners’ club: “We started developing the CBX around 1976,” he wrote. “The biggest problem with the CBX was the weight. In order to guarantee sufficient horsepower, the weight had climbed to more than 200kg and how to get it down was our biggest headache.” For a comparison the team also designed a 16-valve dohc four based on the RCB endurance racers. “It was extremely light and actually much faster than the CBX,” said Irimajiri. “This fact became extremely clear on the test track, but nevertheless we felt there was something exhilarating and exciting about the six-cylinder CBX that was lacking in the four-cylinder. The deep rumble of the exhaust, the feeling of acceleration, the vibration, its smooth high-rev engine; something in the CBX that could not be measured in numbers like speed and weight made it a very sexy machine. If I had to do it over again, I think now I would design the CBX with a water-cooled engine. It would be lighter and probably put out 128bhp.”

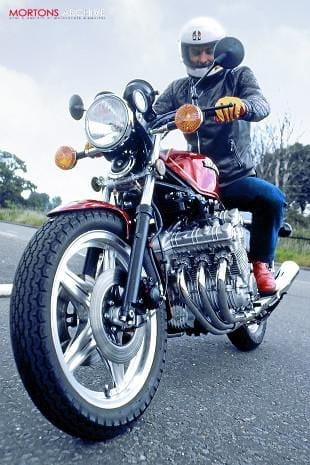

Irimajiri’s project team had done a great job. The impact of the CBX when it was revealed to the European press that Christmas in 1977 can’t be overstated. It was fantastic, both in the bike’s style and specification and the way that Honda’s project team had managed to create a practical motorcycle. Sitting astride the bike in the pit lane at Suzuka, I found it was nothing like as bulky as I’d expected. Of course you could see the cylinder heads below the nose of the fuel tank – at 23.5in across you couldn’t miss them – but being canted forward by 30º the engine and its six carburettors were well out of the way. Up front the controls and instruments presented an image of barely controlled potency waiting to be unleashed. Detailing was exquisite, with adjusters turned from aluminium alloy to keep the weight low. The twistgrip offered just a quarter turn to full throttle, just like a race bike. The test bikes had been brought to the pit lane already warmed up so a touch of the button brought them to life. And what a sound. A snap of the grip was pure joy as the revs jumped – just like the racers of old, though muted – and the rev needle danced into action towards the redline at a heady 10,300rpm.

engine and its six carburettors were well out of the way. Up front the controls and instruments presented an image of barely controlled potency waiting to be unleashed. Detailing was exquisite, with adjusters turned from aluminium alloy to keep the weight low. The twistgrip offered just a quarter turn to full throttle, just like a race bike. The test bikes had been brought to the pit lane already warmed up so a touch of the button brought them to life. And what a sound. A snap of the grip was pure joy as the revs jumped – just like the racers of old, though muted – and the rev needle danced into action towards the redline at a heady 10,300rpm.

According to Honda, the CBX was capable of 140mph and a standing quarter-mile in 11.5 seconds with a terminal speed of 118mph. With claimed peak power of 105bhp at 9000rpm, the engine and its specification read like science fiction. The six 64.5mm pistons and the 53.4mm stroke of the one-piece crankshaft with 120º spacings added up to 1047cc. Thanks to the centre chain-drive to a countershaft, it was slim across the five-speed gearbox and wet clutch, so the footrests and levers – lovely forged alloy items – were narrow.

Inside the huge cylinder head each pot had four valves – 24 in all – opened by individual lobes on the twin camshafts which were driven by two inverted-tooth chains, one to the exhaust and another back to the inlet. Honda’s technicians had a spare bike on which the upper plates that connected the engine to the chrome-moly steel frame were removed along with the cam cover. The multiplicity of valve-gear components was dazzling but we did wonder how long it would take to check the clearances on the inverted bucket followers. In almost every way, at the time of its launch the CBX was miles ahead of any other mass-produced bike.

Moment of truth

The moment of truth came when we were cleared to ride the CBX on Suzuka’s sinuous figure-of-eight curves. Winding it up and dropping the clutch the bike jumped into action, lifting the front wheel under power as I changed up into second and revs screamed to the redline. The CBX’s claimed weight of 590lb, which you felt when you moved it around the pitlane, evaporated on the track. Its acceleration left me breathless, and its handling proved to be more deft than I expected. Riders today wonder how it was possible that we failed to criticise spindly telescopic forks with 35mm-diameter legs and old-style wheel sizes with 350V19 and 425V18 tyres, or for that matter a conventional swingarm with composite bushes. But it was state-of-the-art technology at the time. Indeed, the CBX’s fabricated light-alloy Comstar wheels were the first road-going application of those used on Honda’s RCB endurance racers in 1977. Also the use of rear suspension units with three-position damping adjusters, in addition to preload, was a novel feature, as was the user of tapered roller bearings in the steering head.

Fact was we revelled in the idea of cranking over the six with the footrest extensions skimming the road surface and the crankcases still well clear, thanks the design in which both the crankshaft’s outer webs had been chamfered along with the outer castings. True, the rear end would wallow a bit but that was partly seen as the price of diving into corners from 120-plus as the front end wriggled in protest. Otherwise the steering was impeccable. I left Japan thrilled and humbled in being able to experience such amazing technology first-hand.

Fact was we revelled in the idea of cranking over the six with the footrest extensions skimming the road surface and the crankcases still well clear, thanks the design in which both the crankshaft’s outer webs had been chamfered along with the outer castings. True, the rear end would wallow a bit but that was partly seen as the price of diving into corners from 120-plus as the front end wriggled in protest. Otherwise the steering was impeccable. I left Japan thrilled and humbled in being able to experience such amazing technology first-hand.

It wasn’t until the summer of 1978 that I could test the top speed of the CBX. Changes from the prototypes I rode at Suzuka included a different cylinder head with two additional outer studs and 20 % softer springs on the rear shocks. These were more adjustable with three rebound damping rates and two for compression. Ride comfort was improved but the changes did nothing for the rear end’s waywardness on bumpy surfaces. The conditions on MIRA’s timing straight that July couldn’t have been better and despite sitting bolt upright the CBX still clocked 126.44mph one way. Into the breeze it clocked 119.29mph for a two-way average of 122.9mph. Nothing else at the time could touch it. For the flat-out maximum speeds I took off the mirrors and chinned the tank. After a couple of runs to get the feel of the bike at top speed it clocked a best of 139.19mph downhill, the engine revving to an ear-splitting 9800rpm, uphill it clocked 133.86mph for a two-way average of 136.53mph, making up the world’s fastest showroom motorcycle you could buy.

The first CBX was also a brilliant sprinter, despite its weight. The bike flew through the lights for an average of 11.75 seconds and 116.3mph – but that was as quick as the standard CBX got. A year later, in 1979, I tested a US model in California. This bike had taller handlebars and a softly tuned engine, along with improvements to the chassis and a wider rear rim. The reason Honda’s engineers had detuned the engine – valve lift (down by 0.5mm for inlet and exhaust to 7.8mm and 7mm respectively) and duration was reduced – related to the combined effects of an agreement in Germany that limited peak power to 100bhp, and a need to meet tighter US emissions regulations, but that didn’t account for an almost 20% loss in power for the US models. The softening of the engine heralded in 1981 the CBX’s morphing into a tourer. The final version featured improvements such as 39mm-diameter fork legs, ventilated discs, twin-piston calipers, Pro-link single shock rear suspension, a bigger 22 litre tank, a wider 130-section rear tyre and a fully equipped touring package including the fairing with optional luggage cases. Dry weight increased to almost 600lb (272kg).

Irimajiri, talking to French journalist Jacques Busillet in 2005, concluded: “The CBX was a commercial success, but also a failure as we were not able to give the bike the correct roadholding it deserved. We had a bad balance between weight, power and frame rigidity.”

By then, Honda’s big fours, including the 115bhp CB1100R, were performing better thanks to more power and less weight. In 1982 Honda thought the CBX could not survive only on emotion driven by sound and fury. Owners riding the bike now will tell a different story.

More information and photos in the February 2014 issue of Classic Motorcycle Mechanics.

Thanks to Mel Watkins, also to Ian Foster, who is reprinting his CBX Book www.cam-hk.com/cbx.The CBX Riders Club can be contacted at [email protected]