Doug Webb has an absolutely stunning Triumph. When first you see it, you could easily dismiss it as a show bike from a chrome plater’s, the whole thing shining from its polished alloy engine to the plated hubs and frame. Then you realise that it’s been ridden to the show, rally or club night you’re at, and you wonder how he keeps it looking so good.

I first saw it on a Tamworth and District Classic Club’s weekend outing, on the sort of bright summer’s day when you expect such a bike to be out and about. After all, received wisdom says that show bikes as extreme as this don’t go out when it rains. And, when the weather’s cold and there’s the possibility of salt on the roads, such bikes are hidden away, cocooned safely in a heated garage. Probably with an armed guard to keep potential riders at bay, or am I letting my vivid imagination take over here?

But I saw it again at the CBG Show at Stoneleigh, late in the same year, when the weather was awful and anyone who turned up on a bike was acclaimed a minor hero. It was voted best in show and, after all the back-slapping and photo taking, Doug climbed back on the bike and rode it home. No trailer, no Transit, no Securicor contract to take it from home to show and back again with total protection from the elements. Blimey, this bloke has an award-winning bike and actually rides it everywhere!

But I saw it again at the CBG Show at Stoneleigh, late in the same year, when the weather was awful and anyone who turned up on a bike was acclaimed a minor hero. It was voted best in show and, after all the back-slapping and photo taking, Doug climbed back on the bike and rode it home. No trailer, no Transit, no Securicor contract to take it from home to show and back again with total protection from the elements. Blimey, this bloke has an award-winning bike and actually rides it everywhere!

Not when you talk to him, he’s not. He’s just an enthusiast who loves his bikes and wants them to look as good as possible, so his 1955 Trophy Triumph has loads of neat detail work as well as a lovely paint job and chrome plating nearly everywhere you look. As well as the Trophy, his Honda VFR400 is a beautifully presented example of that future classic line. Did you know that Malcolm Uphill, one of Triumph’s great heroes after putting in the first 100mph lap of the Isle of Man TT course on a production bike, a works prepared Bonneville, used to ride a VFR400? Don’t go knocking these Japanese models until you know who’s ridden them. The point to be taken from all this wandering from the point is that Doug Webb keeps his bikes, whatever their status as classics, in a highly presentable state. Particularly his Triumph.

He arrived at Trumpet ownership after an apprenticeship in motorcycling that started as a kid in Slough, when he and a gang of mates had an old side-valve Norton they thrashed around the local common. They clearly had enough nous to keep out of the local constabulary’s radar and graduated to a 1939 Ariel Square Four with hand-change and a lot more oomph than a tired old Norton plonker.

Where did it come from? “Don’t know,” says Doug. “We bought it between us. I remember it had the carb at the front and, when you’d ridden it through a few puddles, you had to strip the carb and clean it out.”

And what happened to it? “Dunno. One of the lads sold it for scrap, I think.”

Weep, all you Ariel Four enthusiasts, weep.

When he went to work, as people did in those days when they reached the age of 16, he graduated to a Phillips Panda moped to get him to the Electricity Board showroom, where for the next 10 years he developed the silver tongued skills that still shine through today. He moved on from the Phillips – well, any sensible young man would – to a Zündapp K70 and then to a Royal Enfield Crusader Sports.

When he went to work, as people did in those days when they reached the age of 16, he graduated to a Phillips Panda moped to get him to the Electricity Board showroom, where for the next 10 years he developed the silver tongued skills that still shine through today. He moved on from the Phillips – well, any sensible young man would – to a Zündapp K70 and then to a Royal Enfield Crusader Sports.

Ah, now we’re beginning to talk motorbikes, because Royal Enfield’s finest 250 was a tasty little bike with a half-decent performance and more good looks than Elizabeth Taylor. Richard Burton wouldn’t have agreed with that last statement, but he was into that William Shakespeare of Stratford and Dylan Thomas, so he wouldn’t really appreciate a motorcycle produced by craftsmen in the fair town of Redditch, in Worcestershire. Members of the Burton Appreciation Society who read CBG may care to write to The Editor with contrary opinions.

‘After the Crusader Sports, Doug moved swiftly towards a seminal moment in his motorcycle life when he bought a 1958 Triumph Tiger 100’

After the Crusader Sports, Doug moved swiftly towards a seminal moment in his motorcycle life when he bought a 1958 Triumph Tiger 100. Whatever your personal view of Triumphs of that period, only a blind man could deny that they are very attractive machines with their shining alloy and sleek lines, not to mention paint colour schemes that left less inspired competitors wondering how to beat those smart beggars from Meriden. It was, to use Doug’s own words, ‘done up’, a modest way of saying that it looked so good it was voted best in show at the 1971 BMF Rally.

From the T100 he moved on to this particular Trophy in 1973, bought in bits and rebuilt so well that it was featured on the cover of Bike magazine in July 1974. That’s a mighty impressive result for a year’s work, so how come this bloke who’d made a living flogging fridges and washing machines could get bikes looking that good?

From the T100 he moved on to this particular Trophy in 1973, bought in bits and rebuilt so well that it was featured on the cover of Bike magazine in July 1974. That’s a mighty impressive result for a year’s work, so how come this bloke who’d made a living flogging fridges and washing machines could get bikes looking that good?

“Self taught, basically,” is his explanation. So did he apply his detailed knowledge of Frigidaires and Hotpoints to convert a collection of bits into a motorcycle worthy of the cover page of Britain’s best-selling (at the time) bike magazine? Not quite, because by then he’d moved a few miles south to Camberley in Surrey, and had mates who worked in the Royal Aircraft Establishment at Farnborough and at Vickers in Brooklands.

We’ll pause here for a moment, if you please, to honour Brooklands, the great speed bowl in Weybridge, where Britain built its reputation for the speed and endurance of its two-, three- and four-wheeled vehicles that broke countless world records. It included an airfield in its environs and, during the major matter of interrupting Adolf Hitler’s proposed Conquering Tour of Europe 1939-45, it became a development centre for aircraft. Hence Vickers’ presence there.

Back to Mister Webb’s amazingly beautiful Triumph. With mates in the aircraft industry, he had access to polishing skills like you’ve never seen and materials that the man on the street could only dream of. I can remember the bright engineering boys from my home neck of the country getting apprenticeships at the De Havilland factory in Hatfield (it’s in Hertfordshire, and they have a university there these days, doncha know). One told me that a colleague moved into a new house and found there was no dustbin; instead of popping down to the local hardware store like most folks would do, he  had one made in the fabrication shop. But it was made of stainless steel, which in the 1950s was a material the man in the street could only dream of. Apparently the chap concerned paid two packets of fags for a dustbin that probably cost the equivalent of several months’ wages. I’m telling you this to show that, in the Good Old Days, you could get bits made or refinished in aircraft factories to standards that no motorcycle factory could even dream of. Have you ever considered what materials, plant and expensive skills are involved in the polishing of Rolls-Royce jet turbine blades? Apply those to a Triumph Trophy timing cover and suddenly your bike stands head and shoulders above the rest. It’s just a pity that we can’t list the British aircraft companies that have contributed to this remarkable motorcycle, but could I just say ‘thanks, chaps’ to the shareholders?

had one made in the fabrication shop. But it was made of stainless steel, which in the 1950s was a material the man in the street could only dream of. Apparently the chap concerned paid two packets of fags for a dustbin that probably cost the equivalent of several months’ wages. I’m telling you this to show that, in the Good Old Days, you could get bits made or refinished in aircraft factories to standards that no motorcycle factory could even dream of. Have you ever considered what materials, plant and expensive skills are involved in the polishing of Rolls-Royce jet turbine blades? Apply those to a Triumph Trophy timing cover and suddenly your bike stands head and shoulders above the rest. It’s just a pity that we can’t list the British aircraft companies that have contributed to this remarkable motorcycle, but could I just say ‘thanks, chaps’ to the shareholders?

At the 1977 BMF Rally, Doug repeated his success of four years earlier and came away with the best in show trophy – a remarkable achievement for a man who claims no formal engineering skills – and he naturally was well-known in the area, with such an eye-catching bike. Unfortunately, it was the green eye of the jealousy monster that fell on the innocent Triumph and its winning shine, and some delightful soul set fire to Doug’s shed one night. Did he know who did it? “I had a good idea, but I couldn’t prove it,” he explains. “We did have a bit of trouble with the neighbours, you might say.” Hmm, nice folks.

The insurance company paid out and let Doug keep the sad and sorry bike to do another rebuild. The twin Amals had melted in the fire, but the main engine castings had survived well: “They were black, but there was not much damage,” Doug remembers. “I just cleaned the engine out and it was OK.”

But the super shiny chrome finish, which had cost a few weeks’ wages, was gone. So he concentrated on riding the bike, and today he grins when he tells you that he wound it up to 100mph in third gear at the TT one year. “Mind you, it would only do 106 in top,” he grins.

But the super shiny chrome finish, which had cost a few weeks’ wages, was gone. So he concentrated on riding the bike, and today he grins when he tells you that he wound it up to 100mph in third gear at the TT one year. “Mind you, it would only do 106 in top,” he grins.

That’s because the bike has a close ratio gearbox, with a big first gear and the remaining three all close together.

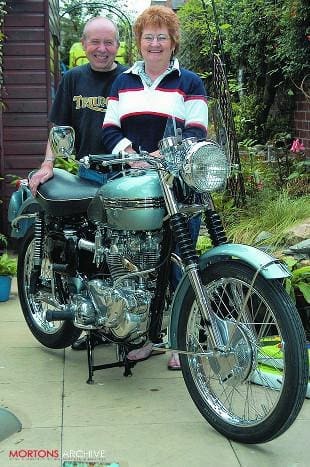

In the 1980s Doug moved to the Midlands, possibly to get away from nasty neighbours, though he didn’t say so. It was a very good move, because in 1996 he married Pat, who is the quiet heroine of this story. In 1998 she had a minor win on the Lottery and promptly handed most of the money over to Doug so he could get his Triumph back to its 1970s chrome-plated glory. Instead of putting it towards a new three-piece or having the kitchen refitted, she made it possible for Doug’s bike to get back its glamour and glory. Mrs Pat Webb, you are a wife-in-a-million, and Doug is a very lucky man.

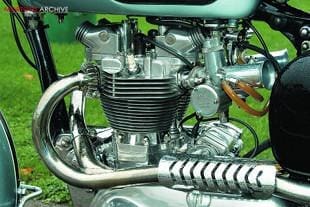

So the Triumph is as shiny as ever and it’s also well-tweaked. The twin-carb cylinder head – one of the rare Delta splayed inlet ones in 500cc form – has both the standard side plugs and 10mm central ones as well, and breathes through two one-inch Amals; it came from a man who’d raced with it, so we can take the gas flowing for granted. Compression ratio is 9 to 1, connecting rods are from a later batch and the crankshaft is the later three-piece version with larger crank journals. Valve gear is polished and the camshafts are E3134 inlet and E3325 exhaust. Sparks are from a BT-H magneto and the lighting system is still firmly rooted in the bike’s origins with a modest six volts.

Front tyre is a 3.00 x 20in Avon, matching the 4.10 x 19 GP rear, while the 8in front brake wears an air scoop – polished, of course – on its backplate. The spoke flanges on the front wheel are scalloped, in another individual touch. The paintwork in the rebuild process was a trainees’ project at the Pittsburg Plate and Glass works where Pat used to be employed, and they laid on a very fine finish in Volvo blue. Goodness me, isn’t this lady keen?

The bike lives in the garden shed, where Doug and Pat can keep an eye on it, and when CBG called it was standing proudly in the back garden. After much oohing and aahing over the details, it was time to take the Trophy out on the road. In the usual way of Sod’s Law, it was about then that the first drops of rain started to fall. Totally unfazed at the idea of this fool being let loose on his scrumptious Trophy, Doug wheeled it down the narrow side passage and kicked it into life. Cor, it does sound well, with a real crackle from what I’m sure was a totally legal silencer (I’m saying that in case the Noise Abatement Society are reading this). You and I know that a warmed over Triumph 500 makes a fine noise if it’s allowed to, and isn’t strangled by restrictive exhaust and silencer; that’s a bit like breeding a fine race horse and putting it between the shafts of a milk cart.

The bike lives in the garden shed, where Doug and Pat can keep an eye on it, and when CBG called it was standing proudly in the back garden. After much oohing and aahing over the details, it was time to take the Trophy out on the road. In the usual way of Sod’s Law, it was about then that the first drops of rain started to fall. Totally unfazed at the idea of this fool being let loose on his scrumptious Trophy, Doug wheeled it down the narrow side passage and kicked it into life. Cor, it does sound well, with a real crackle from what I’m sure was a totally legal silencer (I’m saying that in case the Noise Abatement Society are reading this). You and I know that a warmed over Triumph 500 makes a fine noise if it’s allowed to, and isn’t strangled by restrictive exhaust and silencer; that’s a bit like breeding a fine race horse and putting it between the shafts of a milk cart.

“Don’t be afraid to use it, and if you keep it above 3,000 it’ll be fine,” was Doug’s advice before climbing into the dry of photographer Davies’ car and leaving his bike and me out in the rain. Following them was no problem once I’d got over the combination of big first gear and an engine that needed to be kept buzzing to keep it happy; not quite the sort of whispering passage the po faces of the world would have us restricted to, but it did sound healthy. At traffic lights it needed to be blipped and on the move the suggested 3000rpm meant it didn’t exactly pass unnoticed. Suddenly I was enjoying myself, the old poseur tendency of youth let out of its cell and savouring the chance to ride an outstanding looking bike and make a little more racket than you’re supposed to.

Out in the country, the temptation to wind it up, savour that sharp exhaust and feel the bike drive forward like a whippet let off the leash was too much to resist: drop a gear, open the throttle and zap past traffic, including the photo car, with a crisp mini roar from the exhaust. The bike seemed unaffected by the wet roads, tracking through country bends in surefooted style, its motor immediately responsive to the opening of the throttle, so long as it was in its power band. That morning I had been out on a standard Triumph Speed Twin, a flexible bike to ride that was forgiving if you let the speed drop below 30mph in top gear, with the ability to gently accelerate back up to cruising speed.

Not so this tweaked Trophy. If the rev counter needle flicked below 3000 in third or top, it ignored any rider request to accelerate and got temperamental, but use the close ratio ’box sensibly and the reward was acceleration far better then you’d expect from a 50-year-old 500. It was proof that Triumph’s twin is a supremely adaptable engine, from trials and scrambles (long before motocross was born, my dears) to road racing and record-breaking, it can be tuned to do a range of jobs very effectively.

‘As Jim Davies clicked away, I had a wary eye on the clouds, hoping that they’d move on and let me have at least a brief dry spell to press the Trophy a little harder. No such luck’

There was a break in the riding when we pulled into the car park of the Green Man pub in Clifton Campville for pretty pictures to be taken. This is where the Tamworth & District Classic Club have always met, with the luxury of a separate club room, plus the advantage of a fine pub that serves good food. As Jim Davies clicked away, I had a wary eye on the clouds, hoping that they’d move on and let me have at least a brief dry spell to press the Trophy a little harder. No such luck, this was one of Olde England’s wet days and whoever was shepherding those clouds was doing a particularly thorough job. It continued to persist down. And it persisted throughout the rest of my time on the bike, getting really nasty for the riding shots down a nearby lane, the rain bouncing off the Tarmac.

Look, given the choice between riding in summer sunshine or autumn’s extreme damp, there’s no question which one I’d go for; I love riding a fine motorcycle down country roads with the warmth of the sun on my back. But, even though the rain hammered down, I was willing to keep riding this fascinating, if rather demanding, bike. Its twin carbs do have not the protection of an airbox and its fundamental electrics look remarkably like the 1950s products that have left me scrabbling in a wet gutter in a vain search for a working spark. But it kept on running perfectly. It was as if the bike was saying ‘if you’re daft enough to keep going through this crap, so am I’. So we did. And I didn’t take the soft option of cowering in the car until the downpour eased, which is a huge tribute to the fun level this bike offers.

Look, given the choice between riding in summer sunshine or autumn’s extreme damp, there’s no question which one I’d go for; I love riding a fine motorcycle down country roads with the warmth of the sun on my back. But, even though the rain hammered down, I was willing to keep riding this fascinating, if rather demanding, bike. Its twin carbs do have not the protection of an airbox and its fundamental electrics look remarkably like the 1950s products that have left me scrabbling in a wet gutter in a vain search for a working spark. But it kept on running perfectly. It was as if the bike was saying ‘if you’re daft enough to keep going through this crap, so am I’. So we did. And I didn’t take the soft option of cowering in the car until the downpour eased, which is a huge tribute to the fun level this bike offers.

Eventually it was time to take it back home, where we both arrived soaking wet. The heroine in Pat Webb emerged again: “I’ve got the heating on. Get changed and come and have something to eat,” she insisted. But what about this lovely bike, this chrome-plated one-off that surely would have to be stripped to clean off the combined effects of heavy rain plus mud and whatever else I didn’t see through the rain. “Nah, don’t worry,” said Doug. “I’ll give it wash later. That’s the advantage of all the polish and good paintwork, the mud just comes off it easily.”

So we sat and ate lunch as the rain hammered down on the bike out in the yard, its owner happy to see it get wet. Only then did he reveal that he’d never before heard the bike working hard from anywhere but the saddle – I was the first person he’d allowed to ride it. On such a day as this, when I found it hard to believe that he’d let it out of the shed! The nicest people in the world ride motorcycles.