Focus in on a Kawasaki Z1 or a Honda 750/4 and you pretty much know what you are likely to get; 1970s superbikes with all the hype, cost, alleged kudos, etc. What you also get are the inevitable rivet-counters who come as part of the ownership experience. These perverse individuals will almost certainly point out that your totally unmolested example of either of the above has the wrong pattern seat cover on it or that the pinstripes are two whole millimetres higher than they should be. If luck is genuinely against you they’ll also explain why you genuinely need to pay £600 for four metal-bodied plugs caps that will arc out in the rain… such are the potential tribulations of classic Japanese motorcycle ownership.

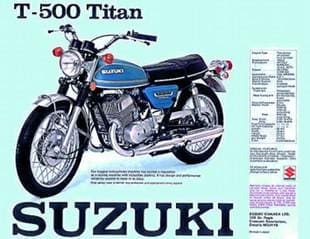

Well, they are unless you opt for a little lateral thought and go for one of the most overlooked, undervalued, ignored machines out there. Retune your sights to Suzuki’s T500 and there’s every chance you’ll be getting more smiles per pound than you ever thought possible. Very few machines of the time genuinely offer so much for so little.

Totally typically for the period, the T500 is mostly about the engine, with the chassis playing second fiddle in this particular ensemble. And in reality that’s neither a bad thing nor a problem. Apart from the unbelievably super-rare T500 500/FIVE with its far-too-short swinging arm, the bike handles rather better than any Japanese bike designed in the late 1960s has any right to. It’s actually something of a stable character, and at a point when many of its peers were hard pushed to stay between the hedges the T500 went through bends without too much trauma or histrionic behaviour.

Totally typically for the period, the T500 is mostly about the engine, with the chassis playing second fiddle in this particular ensemble. And in reality that’s neither a bad thing nor a problem. Apart from the unbelievably super-rare T500 500/FIVE with its far-too-short swinging arm, the bike handles rather better than any Japanese bike designed in the late 1960s has any right to. It’s actually something of a stable character, and at a point when many of its peers were hard pushed to stay between the hedges the T500 went through bends without too much trauma or histrionic behaviour.

But back to that motor… there aren’t many T500 virgins who haven’t walked away from their first ride perplexed and impressed. For crying out loud, it’s only a damn two-stroke twin so how come it’s unbelievably torquey and flexible? Real world practicality is what the bike’s designers set out to achieve, and they delivered it in spades. This was a bike that was on the same playing fields as the 650 British twins in terms of power and driveability; the fact that it was a two-stroke just tended to blow people’s minds. The T500 was supposed to be the bike that couldn’t be built. That may seem like some arcane and obtuse marketing ploy now, but back in 1968 there was more than a crumb of truth about the claims. Until the Japanese got to grips with the concept of two-strokes they were, generally, agricultural, oily, slow and wilfully (and occasionally malevolently) unreliable. Scotts and race-going DKWs aside, the humble two-stroke was very much that, humble and uninspiring. Adler’s 1950s MB250 offered a glimmer of smoke-wreathed hope and, courtesy of some plagiarism, by the early 1960s the Japanese had refined the concept with a wide range of machines.

A few years on saw over-bored 250s gradually upping the ante, but no-one had found much success in going bigger until Suzuki launched the T500 FIVE in 1968, a model which was rapidly superseded by the T500 Cobra. Just how much of MZ’s know-how went into Suzuki’s road bikes is up for debate, but there’s no argument but that a sea change affected the company’s biggest motorcycle to date. In essence the bike was little more than an overgrown T20, or two 250cc trail bike motors nailed together, depending on your level of cynicism or perspective. However, the bike was substantially more than either, and went on to prove it in many ways. In the USA, where standing quarter miles were more important than top speeds, the Cobra/T500 and its descendants were up there with allegedly far more iconic performance orientated machinery.

There was an arcane rule, perpetuated over several decades, which stated that an air-cooled stroker bigger than 350cc was a fundamentally flawed concept as it would prove to be impossible to cool successfully. Given that two-strokes generally actually run cooler than the equivalent four-strokes in the same state of tune, the supposed logic was simply nuts from the off, but urban myths have a strange way of becoming perceived wisdom. Just as Honda’s CB450 had threatened the recognised order of things when it was launched, the T500 did much the same. This was a machine that could tour, sprint, commute and generally hold its head high. The fact that it still does so, even today, is a testament to the rightness of purpose. Know that even now Suzuki still cites the T500’s motor as one of its best, and understand just how good this bike genuinely is.

There was an arcane rule, perpetuated over several decades, which stated that an air-cooled stroker bigger than 350cc was a fundamentally flawed concept as it would prove to be impossible to cool successfully. Given that two-strokes generally actually run cooler than the equivalent four-strokes in the same state of tune, the supposed logic was simply nuts from the off, but urban myths have a strange way of becoming perceived wisdom. Just as Honda’s CB450 had threatened the recognised order of things when it was launched, the T500 did much the same. This was a machine that could tour, sprint, commute and generally hold its head high. The fact that it still does so, even today, is a testament to the rightness of purpose. Know that even now Suzuki still cites the T500’s motor as one of its best, and understand just how good this bike genuinely is.

There’s an inexorable loping nature to the power delivery that’s like little else this side of a quality diesel engine, and it’s oh-so-easy to get wrapped up in the way the bike makes rapid progress. Hook up top (fifth) gear and luxuriate in the way you’re cruising at 70mph a lot closer to 4000rpm than you might think possible. It’s almost the antithesis of what most people might reasonable expect of a stroker, and is probably more in keeping with a big four-stroke single with heavy flywheels.

The carburation is effectively faultless, the clutch feather-light and it’s only the left hand (foot?) kickstarter that really has the ability to throw you momentarily. The seat is actually a good size for two adults and it’s a genuinely comfortable ride; in fact you might even go so far as to suggest that it was actually built to be used and used hard. All things considered, the pragmatist might very well conclude that this bike is one jolly fine all-rounder – and they’d be right.

Being a two-stroke, servicing is simply a doddle. Two sets of points live behind a points cover and the kind Suzuki people even provide you with basic timing marks. Although a dial gauge and/or strobe timing are recommended, many owners have never bothered and their bikes still run fine. Gear oil needs swapping out occasionally, ensure that the engine has a perpetual supply of good quality two-stroke oil and the world is your oyster. There really isn’t a whole lot to do spanner-wise, which may actually upset the serial fettler.

Running and reliability issues are few but well documented, with perhaps the gearbox being the most infamous. Early examples were specified with too little oil for the cogs and fourth/fifth gears used to fail. Boxes marked with a 1200cc volume are the most suspect, but many were modified under warranty or later to hold the latterly advised 1400cc. Whining in the above gears is a sure sign that all is not well. Excess smoking is normally down to a crank seal leaking, but that’s about as bad as it gets. Electrics are typical Japanese quality and although the alternator isn’t super-powerful it is well up to its task. The only other well documented issue relates to the TLS front brake that is unique to the bike. These enjoyed a so-so reputation back in the day that’s probably been made worse with the passage of time and old wives’ tales. Modern friction material allied with a good cable is a reasonable starting point and with careful setting up the unit really shouldn’t be sponsoring a white knuckle ride.

but well documented, with perhaps the gearbox being the most infamous. Early examples were specified with too little oil for the cogs and fourth/fifth gears used to fail. Boxes marked with a 1200cc volume are the most suspect, but many were modified under warranty or later to hold the latterly advised 1400cc. Whining in the above gears is a sure sign that all is not well. Excess smoking is normally down to a crank seal leaking, but that’s about as bad as it gets. Electrics are typical Japanese quality and although the alternator isn’t super-powerful it is well up to its task. The only other well documented issue relates to the TLS front brake that is unique to the bike. These enjoyed a so-so reputation back in the day that’s probably been made worse with the passage of time and old wives’ tales. Modern friction material allied with a good cable is a reasonable starting point and with careful setting up the unit really shouldn’t be sponsoring a white knuckle ride.

Running any older Japanese bike can be a challenge, but the good news is that the bike sold in decent numbers for a fair while. As is always the case, the earlier models would prove to be the hardest to find specific trim parts for, but if an aspirant owner buys with their head and not their heart these problems are likely to be substantially reduced. The bike’s rugged nature effectively means we are dealing with a solid piece of engineering here, not some hissy-fit prone diva of a two-stroke tuned to the hilt and beyond.

The Suzuki has increasingly been emerging from the shadows in the last five or so years, and gradually the industry is tooling up for key parts that were previously obsolete. New, aftermarket, main bearings are available, along with billet con rods and gearbox bearings; in fact from an engine perspective things are actually quite good. Genuine pistons are still readily accessible, thanks to the fact that the T500 and the GT750 use the same items.

However, it’s worth drawing attention to one very important fact. The early Cobra ran a different piston with much thicker rings, and these are generally avoided like the plague due to running issues, ring snagging, wear, and potential seizures. Of course, perversely, that fine purveyor of all useful motorcycle parts, eBay, is littered with exactly these items. There are also modern aftermarket pistons readily available and they’re generally acknowledged to be perfectly viable. The only real parts/spares problem might just be the aforementioned gearbox issues which undoubtedly saw tired examples laid up when cogs, dogs and teeth cried enough. The various ratios were still available not so long ago but not now. However, there are people out there such as Nova Transmissions who have been making racing gearsets for T500 and these can be easily substituted. Once again eBay, and especially the USA version, often turn up a few random gears which are worth grabbing if the price is right.

At the end of the T500’s life there were large numbers of the run-out M model off-loaded worldwide, and there are still enough examples in whole or in part to keep most riders/owners happy and on the road. Although we’ve so far ignored the later GT500, it deserves mention and particularly at this juncture. Effectively a T500 with a front disc, a revised crank, electronic ignition and bigger fuel tank, these are regularly used as parts donors to the earlier machine. It’s worth knowing that the left-hand crank end was revised to run the PEI (Pointless Energy Ignition system) and that the two cranks cannot be used on a mix-and-match basis. The cynic might seriously question the desirability of the GT’s solid state electronics, given that they were a genuine cause of concern back in the day and haven’t improved with keeping. Fortunately, once again, the classic motorcycle world has provided modern and reliable alternatives.

At the end of the T500’s life there were large numbers of the run-out M model off-loaded worldwide, and there are still enough examples in whole or in part to keep most riders/owners happy and on the road. Although we’ve so far ignored the later GT500, it deserves mention and particularly at this juncture. Effectively a T500 with a front disc, a revised crank, electronic ignition and bigger fuel tank, these are regularly used as parts donors to the earlier machine. It’s worth knowing that the left-hand crank end was revised to run the PEI (Pointless Energy Ignition system) and that the two cranks cannot be used on a mix-and-match basis. The cynic might seriously question the desirability of the GT’s solid state electronics, given that they were a genuine cause of concern back in the day and haven’t improved with keeping. Fortunately, once again, the classic motorcycle world has provided modern and reliable alternatives.

By the time the Suzuki T500 was on the streets in significant numbers its original target was in serious decline. The lusty British 650 twins were becoming increasingly old hat and were being supplanted by over-bored, over-stroked heavies, pushed to the limit and sometimes well beyond it. The Suzuki Titan, Cobra, T500, GT500 offered pretty much the same overall level of power as the A65 and T120 but in a totally different package. They also offered substantially lower levels of vibration, reliable charging systems, bulbs that didn’t blow and almost perpetual reliability way in excess of what had gone before. The lack of moving parts reduced maintenance dramatically and Suzuki’s much vaunted Posi-Force/CCI oil injection system made two-stroke ownership a pleasure. The build quality of the bikes was little short of amazing and even the most misanthropic rider would be hard pushed to say that the styling wasn’t bang on the money.

Designed and built from first principles, engineered to last and with a power delivery like little else, the 500cc Suzuki two-stroke twin simply has to figure in every enthusiast’s must-ride-one-day list of top machines. Once experienced it’s unlikely you won’t want to own one; they are bizarrely addictive.