After 80 years of flat twins, it’s easy to forget that the famous spinning propeller badge has also been attached to plenty of machines with a single, vertical cylinder. In fact, BMW’s first ever two-wheeler, released after WWI, when the company was forbidden from making any more aeroplanes by the Treaty of Versailles and needed to diversify, was powered by a single. Displacing about 150cc, the Flink, as it was called, didn’t survive for long.

It’s well known that the boxer era began in 1923 with the launch of the R32. As is less widely appreciated, the first R-series single arrived only a couple of years later. Except for the obvious, in many ways the R39 (BMW’s model numbering system was completely baffling in those days!) was similar to the twin. Same engine orientation, with crankshaft in line with the wheels. Same car-type clutch, gearbox and shaft drive. Same square 68mm bore and stroke used by all the early half-litre boxers, giving an actual capacity of 247cc.

Despite having half the displacement and less than ideal balance, the first single had more compression and revved higher, producing a healthy for the time 6.5hp. That made it half a motorcycle with three-quarters of the performance, which seems like quite a good outcome. Unfortunately, as is always the case, it doesn’t follow that a bike with half the capacity costs half as much to make, so the R39 may not have been as cheap as it needed to be.

After a couple of years BMW abandoned singles again to concentrate on their bewildering variety of twins. But not for long! By 1931 there was far more demand for cheap bikes than expensive ones, hence the R2, a 200cc single of limited performance and basic spec. This one spawned the R4 (400cc) and R3 (yes, 300cc) and R35 (guess!), which in 1937 received BMW’s ground-breaking telescopic forks, an inferior, non-damped version of that seen on the twins.

After a couple of years BMW abandoned singles again to concentrate on their bewildering variety of twins. But not for long! By 1931 there was far more demand for cheap bikes than expensive ones, hence the R2, a 200cc single of limited performance and basic spec. This one spawned the R4 (400cc) and R3 (yes, 300cc) and R35 (guess!), which in 1937 received BMW’s ground-breaking telescopic forks, an inferior, non-damped version of that seen on the twins.

All the latter group used the pressed-steel Star frame, also inherited from the boxers, but the final pre-war models, the R20 and R23, reverted to a tube-type trellis. The R23 engine also went back to the original 68 x 68mm dimensions (who knows why it wasn’t called the R25?) but didn’t last long, because in 1938 BMW put all their efforts into the twins again, very possibly because certain important military customers wanted big, powerful engines.

After a six year period, during which the company churned out an awful lot of sidecar outfits – then a large gap while the Allies picked through the remains of the once mighty Bavarian Motor Works – production eventually resumed in 1948 with the R24. This was a 247cc single, closely based on the old R23. BMW could probably have made updated boxer twins (well, everyone else was, the Allies having helped themselves to the plans!), but they weren’t allowed to make anything bigger than a quarter litre. Apparently a small-capacity, two-stroke flat-twin prototype had been planned in secret, but the finances just weren’t available to produce an all-new model.

The big year of change was 1950, when BMW had risen from the ashes and was allowed to make bikes of any size, even if they competed with British machines. The twins were back, but the R25 also appeared, substantially modified with a new frame and plunger rear suspension. And wonder of wonders, the numbering system was now almost logical, so the following season gave us the mildly updated R25/2.

That lasted until 1953, when the R25/3 came along, complete with smaller 18in wheels with full-width alloy brakes and improved, damped, forks. The power output had steadily crept up and now stood at 13bhp, thanks in part to a new air intake system with convoluted plumbing.

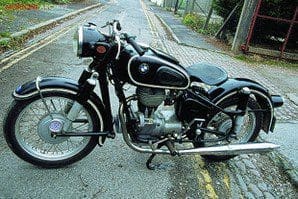

Getting on for 50,000 R25/3s were sold in a three year production run, far more than any of the contemporary boxers. So where are they all now? Well, you can see one here, the oldest of a trio of singles found lurking at BEMW. Yes, that’s BEMW, Bowbury Engineering and Motor Works of Derby, where John Lawes keeps a veritable Aladdin’s cave of classic Beemers.

Although there are those who dismiss the singles as ‘half motorcycles’, you can see that John certainly isn’t one of them. Finding three in the same place is already quite an achievement, but lurking in another corner of the workshop was also a beautifully original 1938 R23. It would have been good to include a pre-war model in the comparison, but ignition coil failure had sidelined it at the time of my visit.

No matter, wheeled out into the blazing Derbyshire mist, we still had most of the post-war BMW singles scene to contemplate. In chronological order, there was a 1964 R25/3, a 1957 R26 and a ’64 R27. I suspect that to a non-motorcyclist the three machines, built over a ten year span, would have been virtually indistinguishable. Even a fairly clued-up classicist might get confused, and if the ’38 R23 had been there I doubt that it would have stood out from the crowd… And they say that British bikes didn’t change much!

The general lines might not have undergone any radical alterations over half a century, but look more closely and there are all sorts of subtle differences. While the basic layout stayed the same, I doubt there are many common parts (unlike with certain long-running British bikes, I seem to recall). When BMW did make a change they seemed to do their best to make it invisible. For instance, to a casual glance the R26’s swinging fork rear end looks very like the R25’s plunger set-up. Perhaps this was because of the culture shock customers already had in dealing with the sight of the new Earles front end?

To digress a bit, I’ve always found it intriguing that having championed telescopic forks (not invented, as it often claimed: hydraulic damping was the innovation) in the 30ss, BMW ditched them 20 years later. Then, when everyone else had adopted telescopics and had come to the conclusion that they maybe weren’t so great, the new ‘Slash Series’ boxers reverted to softly-sprung pogo-sticks. Move forward another decade or so, and BMW come up with the Telelever front end, just when the rest of the world has worked out that normal telescopics are the most effective suspension, their perceived weaknesses being offset by all their good points.

To digress a bit, I’ve always found it intriguing that having championed telescopic forks (not invented, as it often claimed: hydraulic damping was the innovation) in the 30ss, BMW ditched them 20 years later. Then, when everyone else had adopted telescopics and had come to the conclusion that they maybe weren’t so great, the new ‘Slash Series’ boxers reverted to softly-sprung pogo-sticks. Move forward another decade or so, and BMW come up with the Telelever front end, just when the rest of the world has worked out that normal telescopics are the most effective suspension, their perceived weaknesses being offset by all their good points.

The most obvious advantage of Earles forks (and the current models’ Telelever, for that matter) is to reduce dive under braking. This is good, a) because it might stop the undercarriage from grounding out when banking into a corner, and b) because the headlight will illuminate the road more than three feet away while doing so. However, while the theory used to be that the change in steering geometry accompanying fork dive was bad news, it’s now understood that a steeper steering angle and reduced trail is exactly what’s needed to make a bike turn quickly into a corner. Oh well.

One undeniable advantage of an Earles front end is its suitability for sidecar use, because trail is easily adjustable and side loads are resisted more successfully. It seems strange now, but BMW was always very keen to promote the singles as chair luggers. This probably explains why they fitted such a low first gear. The only other time you’d want a ratio that barely gives walking pace at maximum revs is for off-road use. But of course you wouldn’t want to head off into the scenery on a heavyweight shaft-drive single, would you? Well, not seriously now, perhaps, but in the 60s and before, things were different. R-series bikes were used off-road to good effect, notably by John Penton in the International Six Days Trial, as held for the first time on the Isle of Man in 1965.

The R27 was announced in the 60s, and turned out to be the last in the line of shaft-driven BMW singles. Again defiantly similar to preceding models in layout and style, another three horses had been squeezed out of the engine by means of higher compression. 18PS at 7400rpm should be good for about 80mph, which isn’t far short of that achieved by the fastest quarter-litres of the era.

The Bavarian equivalent of ‘the more it changed the more it remained the same’ still applied in many ways, but the R27 did boast one novelty: the engine was now isolated from the frame by rubber mountings. Sound familiar, all you Norton Commando owners? In fact BMW’s system was closer to that used by Sunbeam’s S7 released some 14 years earlier, because with shaft secondary drive there’s no harm in letting the engine shake about in all directions. All it took was some extra brackets on the frame at the front and back with a couple of rubber bobbins in each, plus a flexible head steady hanging from the top tube to resist twist. The simplicity of the system meant that the weight penalty was only about 10lb, which wasn’t a huge increase for a machine already weighing over 350lb ready to roll.

What I hadn’t realised, until John pointed it out, was that even before the R27 came along there were rubber bushes in the engine mounts. This type of ‘semi-rigid’ attachment is common practice on Japanese bikes, and I suspect it would be more effective at reducing a four’s secondary tingles than dealing with the multiplicity of vibrations produced by a single.

As ever, the best way to find out was by going for a ride. The oldest of the trio was selected as the first victim. Ignition is by coil and battery, and to switch on you press the distinctive ‘key’ atop the headlight shell. Although John had started the engine earlier with a casual dab of the kickstarter, there is a certain knack to operating a lever that sprouts sideways on the left side… so that’s my excuse for needing about eight kicks to get it going, possibly after some over-enthusiastic tickling of the Bing carburettor. Every other time from then on, it fired up first go. Interestingly, BMW did actually fit kickstarters on the right side, operating in a normal arc, to some pre-war singles, but the extra complication probably wasn’t necessary for a 250 with such a modest amount of compression.

As ever, the best way to find out was by going for a ride. The oldest of the trio was selected as the first victim. Ignition is by coil and battery, and to switch on you press the distinctive ‘key’ atop the headlight shell. Although John had started the engine earlier with a casual dab of the kickstarter, there is a certain knack to operating a lever that sprouts sideways on the left side… so that’s my excuse for needing about eight kicks to get it going, possibly after some over-enthusiastic tickling of the Bing carburettor. Every other time from then on, it fired up first go. Interestingly, BMW did actually fit kickstarters on the right side, operating in a normal arc, to some pre-war singles, but the extra complication probably wasn’t necessary for a 250 with such a modest amount of compression.

Swinging a leg over the sprung saddle, the R25/3 felt compact and low – and comfortable, although the slightly non-standard bars could have been a better shape. Twisting the throttle, I noticed that the control has a very smooth, light action, a consequence of worm-drive operation, rather than the usual crude drum type with a Bowden cable.

The second thing I noticed was the slight lateral twist produced as the bike tries to turn in the opposite direction to the crankshaft. Another family trait shared with big brother boxer! Also experienced on Moto Guzzi V-twins (but not on other bikes with longitudinal cranks such as Honda CX500, Goldwing and BMW K-series, because another part of the engine has been arranged to rotate in the opposite direction to cancel out the effect), the (in)famous torque reaction is of no concern in general use. The same applies to the other sort of torque reaction going on in the shaft drive, causing the suspension to jack up under acceleration, especially when there’s only 13bhp on tap.

Leaving BEMW’s yard and heading off into the Derby gloom, the incredibly low first gear proved a bit of a handicap. Unless you’re trying to start on a steep hill and/or have a large sidecar attached, it’s probably best to use second and slip the clutch a bit. Otherwise, you get about three yards before an up-change is necessary.

Leaving BEMW’s yard and heading off into the Derby gloom, the incredibly low first gear proved a bit of a handicap. Unless you’re trying to start on a steep hill and/or have a large sidecar attached, it’s probably best to use second and slip the clutch a bit. Otherwise, you get about three yards before an up-change is necessary.

A couple more agreeably clonk-less cog-swaps, and you’re into the direct top, probably with the VDO speedo showing about 40mph. At this sort of rate the single is quiet, relaxed and vibration-free. From the way the engine responds to the throttle (and the aforementioned torque reaction at a standstill), it obviously has plenty of flywheel weight, as was the way in 1954.

Ridden in a manner befitting a 50-year-old (bike, that is…), which to me means using no more than about half to three-quarters of the potential revs and power, the R25 rumbles along at a pace that’s OK for smaller roads out of town, not so good for superhighways or urban dicing. Once I’d negotiated Derby’s outer ringrace road and found some uncluttered lanes, the riding experience was altogether more civilised and pleasant. Stopping to admire the view for a while, the engine ticked over steadily before I pulled the ignition key to the off position. Why won’t my BSA B40 do that? And why won’t it start so easily, I wondered ten minutes later after making another forlorn attempt to take photos in the crepuscular countryside.

Heading back to BEMW’s base in central Derby, I lapped a large roundabout a couple of times to get a feel of the handling (translation: I was temporarily lost). The R25 felt steady and more than a bit like its boxer brothers, I fancied. Finally heading in the right direction again, I pretended to be completely incompetent by closing the throttle at the wrong time going into a corner (this really was deliberate, honest!) to see if the torque reaction would upset it. Nothing to worry about, as it happened. The effect is there if you look for it, but anyone who makes a habit of shutting off going into turns deserves a gentle warning!

I never take any risks when riding someone else’s bike, but when you have an impatient eurobox driving three feet from your (hinged) rear mudguard on a country lane, you really need to keep moving. Having come down the same road in the opposite direction I had some course knowledge, but after girding my loins and throttle hand for a twisty section I was surprised to find that this particular car dropped right back and only resumed station on the next straight bit. Although it was fairly obvious that this bloke couldn’t drive properly, I was rather pleased with the baby Beemer’s handling on slimy roads. A low centre of gravity helps here, I reckon.

I never take any risks when riding someone else’s bike, but when you have an impatient eurobox driving three feet from your (hinged) rear mudguard on a country lane, you really need to keep moving. Having come down the same road in the opposite direction I had some course knowledge, but after girding my loins and throttle hand for a twisty section I was surprised to find that this particular car dropped right back and only resumed station on the next straight bit. Although it was fairly obvious that this bloke couldn’t drive properly, I was rather pleased with the baby Beemer’s handling on slimy roads. A low centre of gravity helps here, I reckon.

Back at base, a short spin on the R26 and R27 didn’t produce any surprises. Both engines immediately felt perkier, as you’d expect with more compression and deeper breathing. The R27 had the unmistakable low revs quiver of rubber mounting, in return for smoothness at the sort of speeds necessary for the motorway age of the 60s. I didn’t go far enough to discover how much better the swinging arm/Earles fork suspension may have been, but it would be interesting to discover whether the R27 frame’s loss of bracing from the engine affected the handling.

As becomes apparent the more you look, older BMWs were built to a standard and not to a price. Thus, although a single had fewer parts and was a bit cheaper to make than a twin, the difference couldn’t have been great. While the R25, R26 and R27 were undoubtedly superior machines, the bottom line didn’t make much sense to the person standing in a showroom wanting to buy a motorcycle. Why have a 250 if you could get a British 650 for the same amount of money?

In the 60s logic gradually crept up on BMW. Having launched a wildly successful new range of cars, the company almost stopped making motorcycles completely. Thankfully, they didn’t, instead choosing to redesign the boxers, making them more accessible (read, ‘cheaper and less odd’) to punters who bought bikes for leisure use. Expensive singles had no place in the new order, however, so the R27 was terminated in 1967.

About 30 years later BMW had a rethink. The F650 that emerged was built by Aprilia, used an engine supplied by Rotax and had chain drive. As a result, it sold for a marketable price and has been a huge success.