Back in the day, the young lads of The Paddock weren’t averse to a quick sprint to demonstrate their riding prowess. Ian Caswell remembers ones particular evening when things got a tiny little bit competitive…

In my early days of knocking around the Paddock there were several of the occasional riders who I knew only vaguely. Their bikes however were well known and a constant source of interest. And it wasn’t just me. Meticulous nightly inspections were carried out by wandering groups or interested individuals, with or without the owners’ presence. Walking the line of parked bikes was always something of a ritual.

The exceptional machines would stand out from the row of fairly standard and well-known bikes. A yet-to-be-repaired scuff from meeting the tarmac often told of recent events long before the owner had a chance to put a spin on his folly, while an unknown motorcycle pointed to new faces or a change of wheels. Either would be good for a bike swap and a blast, a simple ten minutes of road time that could cement friendships for life.

Then there were the specials. A set of expansion pipes, rear sets or dropped bars, usually part of a work in progress as funding allowed, provided hours of discussion on the relative merits of what should be done next and what performance improvements could be extracted from a particular model. Few bikes stayed standard for long, but despite the best efforts of many, no bike came close to the ascetic perfection and immaculate preparation achieved by one fella, named Red. Although always secondhand, Red’s bikes were never seen in less than perfect condition. While many of the rest of us ran scrappers that were continually in need of mechanical tinkering, the reliability and performance of his bikes was absolutely never in doubt.

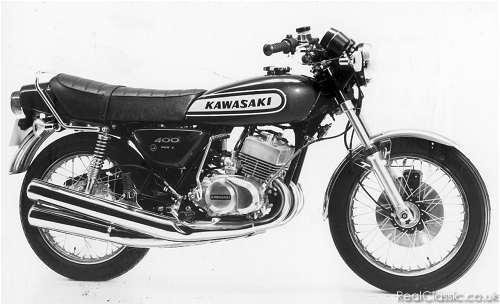

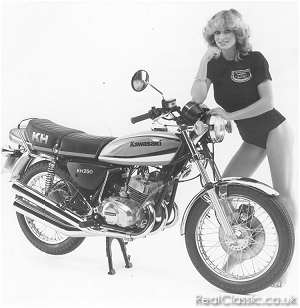

Red was running a Kawasaki triple at one point. It was resplendent, both frame and bodywork, in a coat of red paint even deeper and more lustrous than his own well-cared-for locks. The alloy and chrome sparkled whether lit by sun or street light, and along the smooth, flowing lines of the tank the maker’s name, Kawasaki, was sign written in huge chop stick script. This bike stood out, attracting onlookers like moths to its red flame wherever it was parked. Beyond its impressive visual presence, I never did get to know what modifications lay inside.

It was early in the year and, as evening drew in, the town became quiet. During those troubled days in Northern Ireland when the shops shut in the evening not many people hung around: most seemed to prefer the comfort and safety of their own homes. On a spring night not yet with the true warmth of summer, even here in the supposedly safe commuter belt outside Belfast the streets were largely abandoned to us, the dislocated youth.

Our number that evening was boosted by the last distant stragglers from a Kirkistown race meeting who after tea time fish and chips, were milling around the Paddock checking out the bikes before they headed home. Of course, they could not fail to stop at Red’s Kawasaki, and I noticed fingers pointing out various bits and pieces on it. They were one and all mounted on Yamahas, and since brand loyalties ran deep not everything that was said was guaranteed to be complimentary. As dusk progressed a few of our own got involved with the visitors but before long their discussion escalated. Soon it wasn’t just Kawasaki’s prowess but our own territorial honour that had to be defended. It was at this point that Red was called in.

The easy-going Red broke off from his own conversation with a sigh and ambled over, no rush, not a care in the world. At first he just listened, lightening the mood of the critics with an occasional smile or laugh at their comments but nothing much more than yes or no answers escaped him. Despite this the two camps were becoming polarised behind their chosen spokesmen. Still Red said little and remained at ease with the world, silencing occasional supportive interruptions from behind him with a raised hand. I couldn’t tell whether he was just not taking the thing seriously or if perhaps he had the whole situation under control. At last he spoke.

‘There’s only one way to settle this, you know?’

‘All right’, spluttered the visitor, taken aback.

‘So you’ll race? You can choose the route’ replied Red nonchalantly.

The visitor backtracked. ‘But you know the roads, you’ll have an advantage.’

Red smiled, looking up towards Fred Blair (he of Yellow Submarine fame and a long standing friend of Red’s since their schooldays). ‘We could even things up. I’ll take a pillion.’

Fred didn’t look happy, but neither did he flinch.

I’m sure that this testosterone-fuelled rivalry has been going on since people first learned to ride horses, and while there was no juke box here for timing, the coffee bar racers from a decade or two before would easily have recognised the scene. The visitor could not help but rise to the bait and Red appeared happy to play the line, confident of his own ability to reel in his opponent. His adversary could not reasonably refuse the challenge.

Routes were discussed with some exasperation on our part, as the visitors indeed did not know all the suggested roads. There was mention too of logbooks but nothing came of it; the race was to be for honour alone. Eventually a simple course was agreed, following the shore road out of town through the Ballyholme suburbs until it met the town’s ring road. The bikes were then to blast a fast section on this dual carriageway before turning right, following the road directly back into town, a total of around five miles. Representatives from both sides were sent off to appropriate corners to ensure compliance and fairness.

As we waited for the marshals to get into position, the tension rose. As usual, word had made it to a few nearby watering holes where drinks had been abandoned and a small audience was scrambling to get a ringside seat. Engines were being warmed as in one corner the visitors discussed tactics, while in another our two heroes talked quietly, already saddled for the off. On the hour, the bikes lined up at the end of the Paddock. The two pilots exchanged glances and suddenly the starter’s arm dropped. Revs ricocheted off the walls as the bikes surged forward. There was a brief jostle for position as each rider tried to get the best line around the first corner at the old customs house. The Yamaha slipped ahead, and then they were gone from sight. As their two-stroke mist dissipated in the Paddock we listened to the rapidly departing engines; trying hard to work out positions and to will Red on. Then with distance, came silence. Those left behind in the Paddock were momentarily silent too, listening hard for a last hint of what might be happening out there.

My own thoughts turned to an incident from my childhood when my family lived along the road the racers had just taken. On weekends the sound of bikes or cars travelling much too quickly past our home was far from unknown. The road was cut into a steep slope, with the houses set above this, raised above the tarmac on a bank protected by a stout Victorian stone wall. On one of these weekends my mother who was a nurse had been called out to help with a bike accident, her skills keeping that rider alive until the ambulance came for him. Months later he had returned to thank her, providing an entertainment of appalling revulsion and avid fascination for us children by demonstrating the plate that had been set into his skull. For some strange reason after that, my mother had never wanted either my brother or I to get bikes. I gave quiet thanks for the helmet law we lived with, hoping too that those involved in the current hedonism would made it round in one piece.

In the Paddock the few minutes of waiting seemed endless. Some small groups paced back and forward, while others moved over to the end of the street where the bikes would reappear. Only a few lowered voices threatened the silence as everyone strained again to hear the first hint of the returning bikes. Somewhere in the distance there was a brief and very faint rise of engine note as the bikes crested a far off hill, then another short moment of quiet.

Suddenly the screaming engines were heard again as they raced down High Street towards us. The noise was confused; no single bike was clearly discernible. Things must be close, and with headlights showing first it was difficult to make out for certain who the leader was. The atmosphere was instantly tense, expectant. Then a cheer rose from the group watching at the end of high Street as a bright red bike slowed, checked in case of traffic, then accelerated again to cross the white road marking at end of our domain. Red’s Kawasaki was immediately surrounded while a second or so later a more dejected looking Yamaha pulled in.

The marshals too were not far behind, having left their posts to follow as soon as the two bikes had passed. Even from where I stood it was easy to make out that the rider of the lone Yamaha sitting at the Paddock entrance was not best pleased. As a few brave souls walked over to console him he nodded them towards their bikes, signalling his wish to be away. They uniformly complied. Only at the last moment before their departure did he nudge his bike through the crowd around Red and pass a few words to him from within his helmet. Their subdued group then rode off for home.

|

Period Classic on Now… |

Meanwhile back slaps and congratulations were still the order of the day for Red. When, eventually, there was space for them to dismount, I noticed Fred looked a little pale. His hands were visibly shaking as he pulled off his gloves. It can’t have been an easy trip for him on pillion, and it is certainly not a position that I would have considered filling. Then at second glance, I noticed that he had been hanging on to the back of the back of Red’s bike so tightly that the inside of his fingers were bleeding.

As I say, there were two heroes in this particular race…

————-