Now more than 20 years old you can bag Triumph’s 955i Tiger adventure bike for around two grand. Bertie Simmonds goes big-game hunting…

Words: Bertie Simmonds Pics: Triumph, Bridgestone Tyres, Mortons Archive

Twenty or more years ago, the shrewd amongst us would often eschew the likes of sports-bikes or even sports-tourers for doing distance work and instead we used to enjoy going places on ‘big trailies’.

Big trailies looked like the bikes that took part in the Paris-Dakar rally back in the day. So, they were big, tall bikes with long travel suspension but not light like dirt bikes were. They were often big and heavy and sometimes a little underpowered. They often had panniers on them, like a tourer did – or we would use throw-over soft panniers or tank bags. This made them practical and while not the quickest things on the road they were good for doing long distances on. Basically, the things that made their race brethren good at navigating through Africa also meant the road bikes were dead handy for tackling the North Circular during rush hour, too, so they made dead handy commuter bikes.

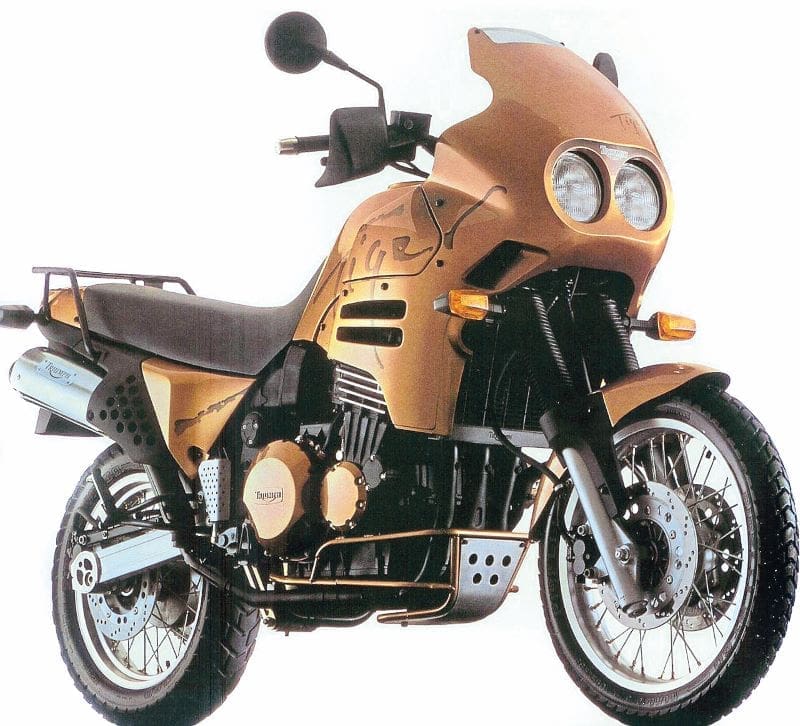

The ‘big trailie’ you see here came out in 2001 BCE, BCE standing for ‘Before Charlie/Ewan’. Of course, after those two gents and The Long Way Round these sorts of bikes were called ‘adventure’ bikes. Strange really, as the rest of us knew that riding on ANY motorcycle was an adventure in itself. But still, it’s a great catchy name for this type of bike so we’ll adopt the modern vernacular from here on in…

Triumph’s ‘Tiger’ has been around for many decades in some form or another (see boxout), but this is one of my favourites so let me tell you why.

I think we should start with those looks first. Yes, it’s something of a bug-eyed beast but, perhaps like Marty Feldman, I rather think it’s got something about it which makes you look beyond all that.

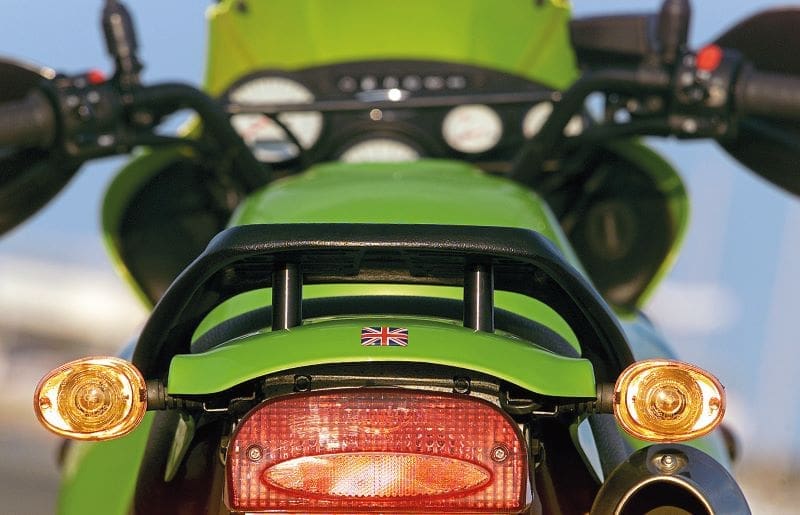

The colour schemes that Triumph indulged in at the time helped – Roulette Green was/is an eye-catcher – but other colours looked good (if more conservative), too, aided by those ‘tiger stripes’ on the flanks of the machine – even if at the front end the stripes look like eyelashes to those bug eyes. But, yes, she has presence.

Now, while I was, and still am, a big fan of the early Hinckley Triumphs, you couldn’t get away from the fact that the noise made by the engine – other than the nice triple roar from the exhaust – was a tad clattery… The word ‘agricultural’ was often used, but by the time the 955i came out things had changed markedly.

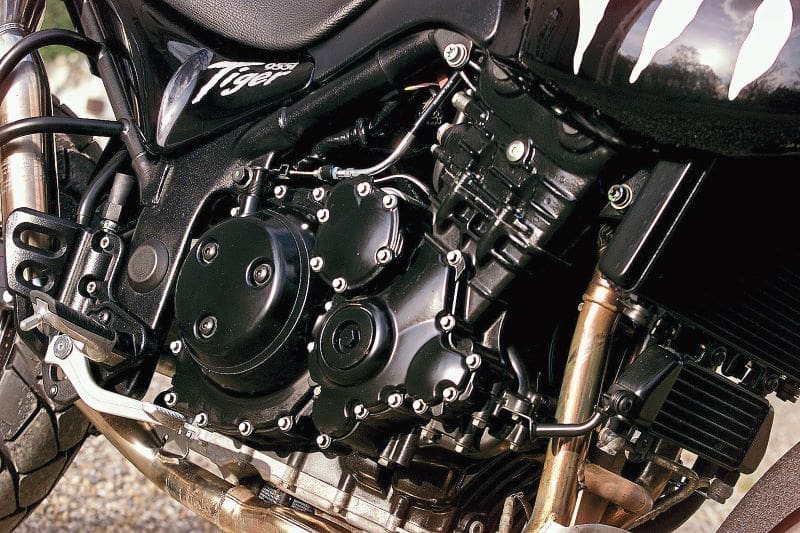

For the 2001 model’s 955cc engine (die-cast cases, a first for Triumph then) the alternator was moved from the top of the engine to the left-hand end of the crankshaft. With no gear train needed to drive the alternator this quietened down the engine quite a bit – especially when sat idling. Other things helped on the noise front, too: the starter sprag clutch was moved to the right-hand end of the crankshaft – the gear train connecting the starter motor to the crankshaft would now only turn when the starter motor was being used. Oh, and a chain, rather than gears, drove the oil-pump.

The difference was that you heard more of the nice noise when starting up the motor even if the end-can was a bit too quiet. Ah yes, the motor. By now the Tiger had what Triumph called the ‘third generation’ of three-cylinder motor: the first being the early 1990s versions using carburettors, the second being the 1997 fuel-injected motors used in the T595 Daytona and T509 Speed Triple. In comparison the 955cc engine was much more refined and pumped out a claimed 104bhp in the Tiger, which on a dyno would normally equate to around 90bhp at the back wheel.

But let’s talk about the motor in a minute, rather let’s get aboard and fire her up. If you move the bike around without the help of the motor, you’ll realise she’s got some lard – 215 kilos dry probably means 240 kilos when ready to rumble. Climbing aboard and you’ll probably have already set the adjustable seat anywhere between 840-860mm – the three-position seat was a nice touch back in the day which few bikes had and on the Tiger it really helps with comfort and ease-of-use, even if you will later moan about the tiddly and daft small screen.

Looking ahead, you’ve got a sea of darkness (well, black) but the instruments are white-faced, all pretty period Triumph. A row of idiot lights give you the standard engine warning, fuel warning, neutral, high-beam, oil warning and indicators in a strip along the top. An LCD odo/trip sits in the 140mph speedo, while below the two small temp and fuel gauges (old school, with needles and everything) sits an LCD clock. Protection to the rider comes from that small fairing and unadjustable small screen ahead; let’s grasp those big bars and get shifting.

The ride…

Pull in that light, cable clutch and let’s use that left foot, shall we? Engaging a gear on an early modular Triumph in the 1990s used to be a loud affair which saw the rider cringe with mechanical sympathy, but by now they were working it out… a bit. For 2001 the gear change came with a revised claw-type mechanism making things more slickety-snick than clunkety-crunch, even if, in comparison, Japanese machines offered smoother gear changes.

I’ve always loved these Tigers. I was lucky enough to do a group test to Assen in 1995 on the original spine-framed 885cc model (T409EN model designation) and loved it almost as much as the V-twin Honda Africa Twin we had and much more than the BMW R1100 GS. The Cagiva Elefant was also enjoyable. Working for a magazine at the turn of the new century, we were also lucky enough to have a long-term 955i Tiger (by now the frame was a steel perimeter design) which I did lots of miles on, so to hear the triple sing when you throw those six gears at it is very nostalgic…

Motor-wise, the older model had a claimed 86bhp, so was easily trounced by the 104bhp the 955i has. You’ve also got a fantastic spread of unctuous stomp available. Claimed, it’s around 68lb-ft at a lowly 4400rpm, but you get plenty of urge from as low as 2000rpm and on the dyno you can see that at 3000rpm you’re getting the sort of torque you’d have gotten from a comparable supersport bike of the time.

So, you simply ride that wave to the claimed power peak at 9500rpm – although you feel it tail off a bit before then… Of course, hitting redlines isn’t what this bike is about, so just be happy to keep the tacho needle between noon and 1pm and you’ll be happy as Larry – I’ve always wondered who Larry was (checks the internet…). Gearing is quite tall and therefore suits A-roads and motorways but there’s still urge-a-plenty at slower speeds.

Triumph was an early-ish adopter of fuel injection – not quite up there with Bimota or Ducati, but they went for it in a big way while many of the Japanese were just perfecting carbs. For 2001 the Tiger got a revised FI system where the oxygen sensor continually monitored the air-to-fuel ratio in order to optimise the engine for perfect running and reduced emissions. I’m guessing it did just that, but what it translates to on the road is that the Tiger hiccups and farts less than the older Hinckley Triumphs did… And it even makes a nice noise through that exhaust.

Being a big trai… sorry, an adventure bike, you want to be walkin’ tall, with a feeling of being above everyone else and, above all, having lots of leverage on those big, black bars. You do indeed have that… and, in fact, the Tiger can chase its tail, or the tail of another bike quite adequately indeed.

For 2001 the 43mm forks were updated to give less dive under hard braking (more of that later) and they do an admirable enough job – as does the rear monoshock – but while the shock has both preload and rebound damping you do wish that the front had some form of adjustment to stiffen it up some, which is a bit of a shame when you think of how much weight you’d be carrying two-up and with the kitchen sink in tow… Triumph clearly listened as later models had uprated forks with a much firmer ride.

The rate of turn on one of these things is never going to be scalpel-quick, but there are owners who’ve fiddled a bit with the back end upping preload and replacing rear shocks to get more height at the rear and speed up steering just a little. To be fair, it’s good enough as-is unless you’re comparing it to something more modern, but it is going to feel a tad ponderous and top heavy so it’s more planted and stable than flickable.

Back in the day Triumph realised this beast was more of a road bike, so you’ve got 17-inch rear wheels/tyres and 19 at the front, and the OE Metzeler Tourance tyres had a semi-chunky look – modern road-biased tyres make a big difference to the handling.

Going for the brakes brings back the biggest bug-bear with the Tiger… While not poor in any sense of the word, even back in the day they were (at best) ‘average’. This was strange as – with Triumph’s 2000 supersport model the TT600 – the firm had shown they could get decent brakes on a bike. It’s just that these twin 310mm discs don’t have quite the power you want on a machine that could be laden with luggage and be two-up. Which is a shame really…

While we’re on the subject of mild disappointment let’s get some other things out of the way. Saying with the wheels, the spoked wheels on the early models are a pain to clean and let’s face it, this is a road bike. From 2004 the bike got cast wheels – easier to maintain, clean and they looked better.

Overall finish is a level above previous offerings from Hinckley but when you’d rock up at the chippy after a long day in the saddle and scrutinise your mate’s 1150 GS or Africa Twin, in comparison the Tiger would have more exposed bolts and in the cockpit even the odd exposed wire.

Going the distance also means you need to have plenty of fuel and good economy and – rereading my old notes from way back when – the Tiger wasn’t quite as good as the competition on a long haul. The 24-litre tank was plastic (Triumph were one of the first manufacturers to do this) and you’d get a good 200 miles before the orange fuel light began to glow, but the figures were pretty low compared to other bikes mpg-wise.

And this was often the thing with the Tiger and other Triumphs using this motor – you do need to make sure they run sweetly. Many owners would fit different end-cans (Triumph even did one) but they need to be set up for them. When buying, do ask if other engine maps have been used. Other issues: fork gaiters can hide knackered fork seals so look before you buy; suspension linkages have been known to seize; fuel lines can crack and age prematurely; reg/rectifiers can fail and fuel drain pipes at the back of that plastic tank can get clogged with stuff, pushing water back into the tank. Oh, and do check if the valve clearances have been done – they need to be done every 12,000 miles but many owners don’t bother.

If this all sounds a bit much – it’s not really… It’s just that the bike was around for quite a while and the owners have loved it and have learned lots about it: forewarned and all that…

Price-wise, you’re in for a treat… These things were £7599 new just over 23 years ago but today the lovely three-cylinder curio can be had for as little as a grand upwards. Yup, that’s right. We’ve seen them as low as that for a high-miler. Generally, Triumphs and these sorts of Trumpets in particular attract a more serious, responsible and ‘grown-up’ sort or rider and owner. So the chances are that services haven’t been skimped on. We also know that these engines can go on and on (my own Speed Triple has almost 70k on the clocks) and the sort of bike it is means that many are resplendent in all manner of official Triumph kit.

Oh yes, because at the time Triumph were really starting to realise that we were suckers for all these extras, they made sure the Tiger had many accessories to choose from. These included (deep breath time): an alarm/immobilisor; higher screen; sports screen (tinted or clear); panniers (colour co-ordinated, of course) with the right-hand one scalloped to fit around the exhaust. A top-box (45 litres, can hold two full-face lids); tank bag (eight litres can expand to 16); louder end-can; heated grips (a must); mudguard and rear guard extenders; and a centre-stand – vital to lube that chain…

Of course, a grand is a bargain basement one, so you’ll be happy to know that a very tidy one can be had for £2500 and a tidy one with very low miles will still be under three grand. Bargain!

So, would I have one of these? Well, actually, yes… Perhaps not the original 2001 model, but from 2004 the bike had stiffer front suspension, panniers, centre-stand and heated grips as standard, and had the cast wheels and a new swingarm. The one I’m riding in this article is a 55-plater and was sweet as – especially with the then-new Bridgestone TrailWing tyres fitted.

I mean, come on: an adventure bike, with that Triumph triple howl for just over two grand? What’s not to like…

Tiger, Tigers!

The Tiger name has been in the Triumph range since the 1930s – the first of which won three gold medals at the 1936 International Six Day Trial – but we want to talk about the Hinckley Triumph Tigers here from the early 1990s-on.

Introduced in 1993, the 885cc Tiger (model code T409EN) formed part of Triumph’s early modular range of machines and is known by fans/owners as the ‘Steamer’.

Sharing the same tubular steel spine frame as the other early bikes and powered by the Trident’s carburetted triple engine, it was retuned to produce 84bhp. It was, however, the first Triumph to feature an injection-moulded plastic fuel tank.

This Tiger soldiered on until 1999 when the first fuel-injected Tiger (model code T709EN) was produced. Powered by Triumph’s 885cc fuel-injected three-cylinder engine, the 1999 model boasted a completely new chassis (steel perimeter) to move its focus toward a more touring-orientated role and updated aesthetics even if it used the old 885’s swingarm complete with eccentric chain adjusters.

For 2001 the aesthetics and chassis were carried forward but the motor was changed to a retuned (well, detuned) version of the Daytona 955i’s three-cylinder motor; panniers and top-box were an optional extra.

In 2004 for the 2005 model year a new swingarm (with traditional chain adjustment), uprated forks (stiffer springs), centre-stand as standard, panniers, heated grips (ditto – standard) and 14-spoke cast wheels were introduced.

From 2007 the even more road-oriented Tiger 1050 came in with 17-inch wheels front and rear and ABS braking was introduced. Today the Tiger name carries on with a 660cc, 850cc, 900 and (updated for 2024) a 1200cc range – some more road-biased and others more suited for true off-roading adventure.

SPECIFICATION

955i

Type: Liquid-cooled, DOHC, in-line 3-cylinder

Capacity: 955cc

Bore/Stroke: 79 x 65mm

Compression Ratio: 11.7:1

Fuel System: Multipoint sequential electronic fuel injection

Clutch: Wet, multi-plate

Gearbox: 6-speed

Frame: Tubular steel perimeter

Swingarm: Twin-sided, aluminium alloy with eccentric chain adjuster (2004 on aluminium alloy)

Wheels:

Front 36 spoke, 19 x 2.5in

Rear 40 spoke, 17 x 4.25in (2004-on cast 14-spoke wheels)

Tyres:

Front 110/80 V 19

Rear 150/70 V 17

Suspension: Front 43mm forks with triple rate springs

Rear Monoshock with remotely adjustable preload and rebound damping

Brakes

Front Twin 310mm discs, 2 piston calipers

Rear Single 285mm disc, 2 piston calipers

Length: 2175mm (85.6in)

Width: 860mm (33.8in)

Height: 1345mm (52.9in)

Seat Height:840 – 860mm (33.1 – 33.8in)

Wheelbase: 1515mm (61in)

Rake / Trail: 28 degrees / 92mm

Weight (Dry): 215kg (474lb) wet: 239 kilos (526lb)

Fuel Tank Capacity: 24 litres

Maximum Power: 104bhp at 9500rpm (90bhp rear wheel)

Maximum Torque: 67lb-ft (92Nm) at 4400rpm