Jonathan Hoare meets three BSA twins (and a Bantam) and revels in that old Miller magic at the Manor

I never realised that the supposedly humble BSA could be quite so glamorous. Just look at that glorious gold on their Golden Flash and the pearlescent green on the A7 Shooting Star (the term ‘metallic’ came later). Even the 1961 A10 is as bright as a button. Just how, in those postwar days of the early 50s, did BSA manage to produce such beautiful bikes as these? And why can’t today’s manufacturers produce anything to match the class of this trio?

These questions and many more sprang to mind when Sammy Miller invited me along to take a look at these three Beezers which sit in his classic motorcycle museum. Considering it contains some of the rarest, most exotic bikes in the world, the choice of three everyday bikes of the 50s and early 60s might at first seem odd. I just had to ask why?

Sammy’s response was immediate; ‘I thought the three bikes together would look stunning. We spent a lot of time and effort restoring the bikes and particularly matching the colours. These three are absolutely spot on. We employ a local man to spray our machines and, to ensure accurate reproduction, we use samples from under the tank or in the toolboxes as a reference. It’s very difficult to match the original colours and some people just don’t achieve it’.

|

When Sammy said he thought the bikes would look stunning he was right. Many of the machines in his New Milton museum are vastly more exquisite, not to mention expensive, but in visual terms it would be hard to beat these three. The invitation from Sammy came shortly after a very successful BSA Day, a regular event held at his Bashley Manor museum. Not only are the doors are thrown open but Sammy also gives riding displays, a tour of his workshop and presents a variety of prizes to the BSA owners. It seemed fitting that I should return once again to admire three more immaculate BSAs. As we walked through the impressive, paved courtyard, it dawned on me just how massive an operation the museum was, with a café to the right, workshop to the left and ahead of us the vast display of fascinating classic bikes. In the space remaining Sammy has somehow managed to fit in his offices and a mail order business which supplies parts for ‘Millerising’ machines. Within minutes he was wheeling out each machine from the museum, whipping them around corners and amongst the other exhibits as if they were weightless. Just how does he do it? No wonder he has over 1150 wins on the race track and trials course to his credit because his sense of balance is supreme. |

BSA A7 stuff on eBay.co.uk |

First out was the 1954 A7 Shooting Star, resplendent in its two-tone dark green frame and light green bodywork. The plunger-sprung 500cc twin was well thought of by riders of the day as being a solid, reliable workhorse and is reputedly one of the smoothest of the BSA twins. Some riders even preferred it to the Golden Flash because it was more pleasant to ride. With its smaller engine and less power output it wasn’t so inclined to accentuate any wear in those rear plungers. There is some debate as to whether a rigid or plunger sprung frame is preferable in terms of handling. The rigid is less likely to weave on a bumpy road, whereas the plungers at least provide a token nod towards comfort for the pilot, provided they are well set up.

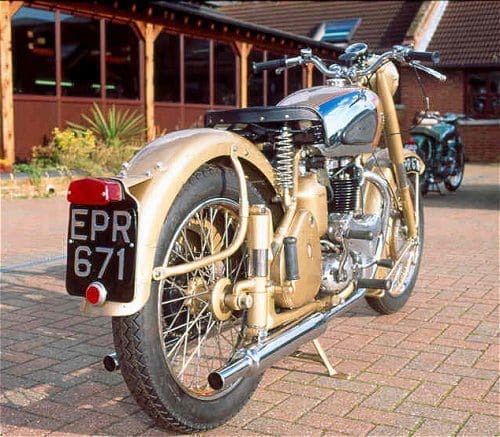

When Sammy produced his next bike, the 1952 Golden Flash, I just couldn’t believe the colour. It glittered with masses of chrome and polished engine cases — I will freely admit that it is quite the most attractive machine I’ve seen in years. And to think that it was highly regarded as a sidecar tug. Sacrilege! In solo form the Golden Flash was one very fast machine and was tested at a smidge over 100mph in 1950 and covered the standing quarter mile in just under 16 seconds. What a waste to attach it to a sidecar!

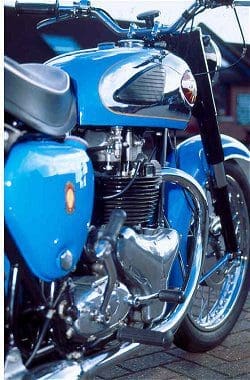

Last but not least out of the museum was the dear old 1961 A10 with its somewhat less flashy suit of blue clothes. I felt that she was something of the poor relation to the other two more desirable bikes, although with her full rear suspenders perhaps she was the more useable machine amongst them. She also differs from the earlier bikes with her headlamp cowl, introduced in ’58. But if you get the chance then go and take a close look at the Shooting Star’s nacelle – it’s nothing short of a work of art!

Last but not least out of the museum was the dear old 1961 A10 with its somewhat less flashy suit of blue clothes. I felt that she was something of the poor relation to the other two more desirable bikes, although with her full rear suspenders perhaps she was the more useable machine amongst them. She also differs from the earlier bikes with her headlamp cowl, introduced in ’58. But if you get the chance then go and take a close look at the Shooting Star’s nacelle – it’s nothing short of a work of art!

Certainly, when I asked Sammy which of the bikes he preferred he went straight for the Golden Flash saying, ‘Well, its everyone’s favourite, isn’t it?’ Well no, actually, as I was to discover when Bob Stanley, Sammy’s right hand man, wandered across for a chat. Bob has worked for Sammy since 1972 when Sammy had just six bikes, a far cry from today when he owns 90% of all the machines on display at Bashley Manor. Bob answered Sammy’s advert and has stayed with him ever since, now restoring machines for display in the museum and occasionally for customers. Bob the Re-builder, then…

As a skilful engineer, his opinion was clearly a matter of both form and function. ‘I prefer the Shooting Star,’ Bob announced without hesitation. ‘Just look at the deeply valanced mudguards on the Golden Flash! The Shooting Star’s are much slimmer and more attractive. And,’ he added conspiratorially as if he had an ace card up his sleeve, ‘the Shooting Star is the only one with manual advance/retard!’

I looked at him agog, awaiting the final revelation. ‘It’s simple, with these older bikes you never know if their automatic units are stuck on full advance and are going to break a leg when you kick start them. With the manual lever you have total control’. So that’s it, the A7 for Bob then. The final clincher is that the dark green frame boasted by the A7 is something of a rarity as it was only produced in that colour for eight or nine months. Apparently the colour is identical to BSA’s bicycles and Bob suspects that, when BSA ran out of black frame paint, they may have borrowed some green from the bicycle department nearby!

All of this rather leaves the basic A10 in the shade. She doesn’t have the flashy paintwork or the glamorous image associated with either the Golden Flash or the Shooting Star but she certainly possesses crisp clean lines and a far less ‘chunky’ appearance. Sadly, the engineer and the racer were quick to point out her major weakness – that Bowden cable operated rear brake with a cross-over linkage. The cable came off in Bob’s hands as he demonstrated it to me while Sammy described it as a ‘built-in anti-lock brake’, explaining that even at its best it was only ever soft and squidgy.

Interestingly, only about eight out of the entire collection of bikes on display within the museum are non-runners and even then only because some of the vital parts were removed before Sammy bought them. It’s obvious that both Sammy and Bob take great pride in the fact that most of the machines are in working order and are not merely museum exhibits. So don’t be fooled into thinking that these machines are mere objects for static display, oh no. Even the rarest and most complex machines, such as the Guzzi V8 and BSA MC1, get a workout by Sammy who thrashes them around his courtyard on open days. It just takes a while to prepare them!

Sammy then offered me the opportunity of a one-to-one tour of his workshop. We set off at a fast pace (Sammy works at nothing less) to view the latest project, a 1926 Zenith Bradshaw. Actually, it was little more than a bare frame and a hand-crafted tank of alloy, based on the original dimensions. How do they do that? Even more to the point, how on earth do they keep track of all the components? You need to bear in mind that Sammy and Bob can restore up to three bikes in three months, when working flat out.

I wandered off to browse amongst the other bikes on display. The truly impressive Moto Guzzi V8 sits near to the entrance. V8? Well, yes, eight carbs, eight coils, two sets of four points – move on swiftly! Sammy’s famous Ariel HT5, GOV 132 (yes, the very one) lurks around the corner, below an astonishing list of his trials successes. Sammy joined me to point out his streamlined, 250cc NSU Sportmax, whose massive fairing he refers to as ‘the office’.

I asked him how he’d come to be so incredibly successful at both road and trials riding. Even in his book, ‘The Sammy Miller story’, Jeff Clew refers to that ‘Miller Magic’. In reply to my question Sammy said, ‘Anyone can race a bike, but you need that certain something from inside of you to build on’. Clearly a day at ‘the office’ for Sammy wasn’t an every day experience, because he rode the NSU to devastating effect at a number of road races in 1955. These included the Skerries 100, the Ulster Grand Prix, the Italian Grand Prix and, to finish the season, the international meeting at Aintree where he broke the lap record.

As I meandered upstairs, alone, I came across the only known working model of a 1000cc, three-cylindered Scott in the world. It dawned on me that, for the classic biker, it is unlikely that there is a collection comparable to this anywhere in the world. My gaze then fell upon a BSA, a tiny Bantam 175cc trials replica, whose registration number PCV 992 I knew only too well. It was Brian Potter’s bike, a machine that had been featured in classic magazines. I’d met him on the Isle of Wight at a recent classic bike show when he’d told me how he’d arrived on the Island’s ferry. His was the only vehicle aboard, one tiny Bantam on a huge, multi-million pound ferry.

Naturally, the crew treated Brian to a cup of tea in the staff quarters. He almost received an ovation from onlookers as the crew lowered the ramp and he rode off! And then the sad truth dawned on me as to why his bike was in Sammy’s museum. Brian had passed away on 15th September 2002 and his family had kindly presented his bike for display in the museum. Brian was a jovial man who clearly loved classic bikes and the people involved with them.

It was then that I realised — it’s not necessarily the bike that you ride, it’s what you do with it that matters. In this respect any of the three featured bikes would provide sterling service. They are the most marvellous examples of BSAs as they left the factory, and I owe a debt of gratitude to Sammy for allowing me the opportunity of spending a thoroughly enjoyable day at Bashley Manor and for making the bikes available to me.