NB: Continued from Norton’s pre-war history

Norton kicked off civilian production after WWII with two models, the 16H and Model 18. By September 1946 the range had grown: Big 4, 16H, Model 18, ES2, two Internationals plus 350/500 racing models and a trials machine. Things looked good, but weren’t quite so under the covers. Craig rejoined Norton after serving time at BSA and AMC and both Mansells pulled out, which pleased the new managing director Gilbert Smith. An amicable shift it was claimed, but clearly there was ill will.

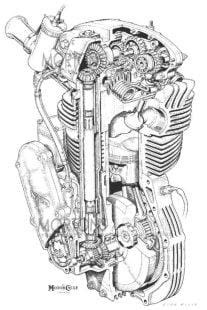

Norton continued their winning ways on the Continent, at the Ulster GP and in the Island, with south London motorcycle shop owner Harold Daniel taking the 1947 Senior TT and Eric Briggs scooping the Junior and Senior Manx GP. A good return to racing, but the opposition was getting tougher. However, Norton embarked on two new exciting ventures in 1948. They hired former Royal Signals motorcycle instructor and BSA trials rider Geoff Duke to help develop and ride the Rex McCandless-designed 500T trials model, and in November 1948 they launched their first radical new design for three decades. Designed by Bert Hopwood, and coded the Model 7, it was a 497cc ohv parallel twin. With the launch Norton had given in to popular demand but the Model 7, soon named the Dominator, was another landmark Norton and although much reworked and enlarged was to remain until the late Seventies, then tagged the Commando.

Artie Bell took the 1948 Senior TT, Eric Oliver the first of his four World Sidecar titles in 1949, while Harold Daniel took the year’s IoM Senior and significantly for a waiting world trials star, Geoff Duke won the 1949 Senior Manx GP, while over the pond Ohio star Dick Klamforth had earlier won the Daytona 200 miler. Models were little changed as Norton moved into the next decade, but to squeeze more power for the ohc Manx motor it went double knocker for the first time. A move forced, perhaps, by ever-mounting problems with the Norton/BRM proposed racing 500cc – four development.

Artie Bell took the 1948 Senior TT, Eric Oliver the first of his four World Sidecar titles in 1949, while Harold Daniel took the year’s IoM Senior and significantly for a waiting world trials star, Geoff Duke won the 1949 Senior Manx GP, while over the pond Ohio star Dick Klamforth had earlier won the Daytona 200 miler. Models were little changed as Norton moved into the next decade, but to squeeze more power for the ohc Manx motor it went double knocker for the first time. A move forced, perhaps, by ever-mounting problems with the Norton/BRM proposed racing 500cc – four development.

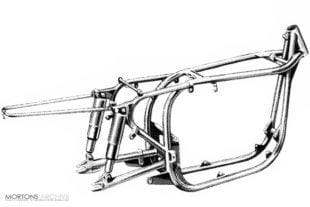

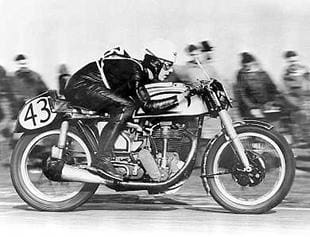

But Norton had one more Manx card up its sleeve for 1950. Duke kicked the year off winning the Victory trial, with Arthur Humphries taking the sidecar class. Billy Matthews led home Klamforth at Daytona on Francis Beart-prepared Nortons and a new frame was under test, then tried by Artie Bell in the Island in late 1949. Designed by Ulsterman Rex McCandless, after some years of development, the frame was approved by Gilbert Smith and finally unveiled to gasps, in a high-drama, cover off at the last moment ceremony, for Norton’s new glamorous star Geoff Duke to ride at Blandford Camp, Dorset. The fairytale was a Norton/Duke win at record speed and a new lap record, helped too by engine development work by former Polish fighter pilot and Warsaw University lecturer Leo Kuzmicki.

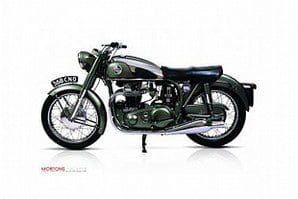

Norton made a clean sweep of the 1950 Senior and Junior TTs, taking the top three places in both races but, possibly even more significantly, Umberto Masetti won the 500cc World Championship on a Gilera four. The multis were on the march, although the Manx singles were yet to fight another day, thanks to their slim profile and superlative handling. Despite its racing success, the McCandless frame, famously nicknamed the ‘featherbed’ by veteran works racer Harold Daniel, was to remain a racer’s tool for a little longer, but was finally spotted in prototype form wrapped around a Dominator twin engine at Continental paddocks during 1951. Unfortunately, the dark clouds were building up for Norton, who’d dominated the world for so long, but were to slide from the GP racing scene and finally from the market place.

Again Norton dished out more of the same on the 1951 racetracks. Geoff Duke, 28, took the IoM TT 350/500cc double, Ulster GP and Spa doubles, and further wins to become double world champion. Eric Oliver, passengered by Lorenzo Dobelli, took his third world sidecar title and, riding 500cc Dominator Featherbeds, Jack Breffitt, Dick Clayton and Rex Young secured the year’s ISDT Manufacturers’ Team Prize.

Outwardly the future looked rosy, but finances were slipping and the majority share-owning Vandervells were considering their and Norton’s future. Yet again Norton looked good in 1952 with production Featherbed-framed Dominator roadsters – albeit export only – a 350cc world title for Duke and the sidecar crown for Brummie Norton tester Cyril Smith, passengered by Bob Clements. But the cracks were worsening. They missed out at the Manx GP – the first time since 1931 – and Geoff Duke, after keeping everyone in suspense by trying four wheels and holding protracted discussions with Bracebridge Street, lined up for Gilera in 1953 alongside Norton’s 1952 Senior TT winner, Irishman Reg Armstrong. The financial situation worsened yet again and their annual production was down to around 10,000 machines per year.

In February 1953 a merger with AMC – owners of AJS, Francis-Barnett, James and Matchless – was announced. Although Norton stayed at Bracebridge Street for another 10 years, gradually many leading employees drifted away. But all wasn’t gloom. Eric Oliver with Stan Dibben gained his and Norton’s last World GP cro wn winning the 1953 sidecar class, while Rhodesian Ray Amm took the 1953 TT 350/500cc double and the Senior in 1954. Relations between Norton managing director Gilbert Smith and AMC soured, taking a further battering in 1956 when London bosses reappointed Bert Hopwood, whom Smith had fired seven years earlier. Gilbert Smith parted – invited to resign – with Norton (AMC) in February 1958 after 42 years at Bracebridge Street and soon died, aged 62. Backtracking to late 1954, the Featherbed Internationals were dropped from the 1955 range, although they remained available to special order until 1958, outperformed by BSA’s Gold Star, the DBD34 delivering the final blow.

wn winning the 1953 sidecar class, while Rhodesian Ray Amm took the 1953 TT 350/500cc double and the Senior in 1954. Relations between Norton managing director Gilbert Smith and AMC soured, taking a further battering in 1956 when London bosses reappointed Bert Hopwood, whom Smith had fired seven years earlier. Gilbert Smith parted – invited to resign – with Norton (AMC) in February 1958 after 42 years at Bracebridge Street and soon died, aged 62. Backtracking to late 1954, the Featherbed Internationals were dropped from the 1955 range, although they remained available to special order until 1958, outperformed by BSA’s Gold Star, the DBD34 delivering the final blow.

However, Norton raised their parallel twin game, opening out their 497cc Dominator engine to 596cc, giving the much-loved Featherbed Dominator 99 in 1956 as well as a standard-framed variant. A 350cc ohv single was reintroduced and, for the rest, it was business as usual, with more models gaining the Featherbed frame over the coming years. With Duke/Gilera winning the 1953-55 500cc world crowns, Guzzi riders Fergus Anderson, Bill Lomas and Keith Campbell the 1953-57 350 titles and Wilhelm Noll’s BMW, passengered by Fritz Cron, wresting the 1954 sidecar title from Eric Oliver/Les Nutt, Norton’s GP supremacy was drawing to a close.

Exhausted by conjuring up more wins from Norton’s superb but ageing single against the raw power of Gilera and MV Agusta, race-team leader Joe Craig retired from Norton on 1 December 1955, aged 58, married Nellie van Wijngaarden – widow of Piet van Wijngaarden – and moved to Rotterdam. Sadly Craig was killed in a 1957 road traffic accident.

Norton, for whom racing had been everything, were gradually to move away from the GP arena as the Manx, despite further modifications, was outperformed by the continental multis. But not before Mike Hailwood scored Norton’s last single-cylinder TT victory in 1961 helped by tuner Bill Lacey. Londoner Godfrey Nash won Norton’s last 500cc GP (Yugoslavia 1969) and Ron Haslam scored Norton’s last 500cc GP point (Donington 1991).

Norton, for whom racing had been everything, were gradually to move away from the GP arena as the Manx, despite further modifications, was outperformed by the continental multis. But not before Mike Hailwood scored Norton’s last single-cylinder TT victory in 1961 helped by tuner Bill Lacey. Londoner Godfrey Nash won Norton’s last 500cc GP (Yugoslavia 1969) and Ron Haslam scored Norton’s last 500cc GP point (Donington 1991).

Tuners with long associations with Norton, led by the likes of Francis Beart and Steve Lancefield (who hated the word tuner, preferring the title racing motorcycle engineer) kept the famous marque’s flag flying. The last major batch of Manx Norton racers was built in 1961 and the last 350cc (40M) and 500 (30M) Manx racers were built from spares in 1963.

Back to the roadsters. The last side-valve 16H models were built in 1954 as were the Big Fours – by then 597cc models. The 19S 600 single continued until 1958, while the 350cc single Model 50 and 500cc ES2 remained until 1966. However, by this time they were AMC-derived models with the immortal 490cc single finally disappearing three years earlier in 1963.

On the Dominator twin front, the 497cc 88 remained until 1963, supported by the 88 Nomad 1960, de-luxe 1960-62 and 88SS 1961-66. The military side-valve 497cc twin appeared briefly in 1953. The 596cc-derived Featherbed models were 99 1956-62, 99 Nomad 1958-60, 99 De Luxe 1960-62 and 99SS 1961-62. Enlarging the 99 to 646cc gave the 650 series, beginning in 1961 and ending in 1970 with the Mercury, the final production Featherbed Norton. Norton enlarged the Dominator engine further to give the 745cc Atlas 1962-68 and derivatives including the P11, N15CS and Ranger. With production still around 200 models per week in the late Fifties, Hopwood/AMC knew Norton needed a new catchy range.

Along with Doug Hele and Bill Pitcher, Hopwood came up with the over-square parallel twin 249cc lightweight launched to rave reviews at London’s 1958 Motorcycle Show. It was a new, four-speed unit engine design housed in an AMC two-stroke-derived rolling chassis named the Jubilee, in commemoration of Norton’s 60-year history.

Hopwood planned Norton to move down-market into the utility market. The Jubilee 1959-66 was joined in 1961 by the up-rated 349cc Navigator and the 383cc electric start Electra in 1963. Both larger models continued until 1965.

Many diehard Norton fans hated them. ‘Their’ Norton factory built only top-range models and, for AMC, the smaller twins didn’t sell in the volume needed for survival. Regardless of quality, hindsight tells us Norton’s Jubilee launch timing was too late. At about the same time, Honda went into quantity production of their 250cc parallel twin, the high-revving ohc Dream, with its concept loosely based on an NSU design of which Mr Soichiro Honda was a fan. Soon 250 Dreams would start landing in the UK.

However, all wasn’t gloom. Londoner Paul Dunstall had taken a Dominator 99, Manx-ised the rolling chassis, fitted twin carbs, magneto ignition and upped the compression to win only the second race he’d entered at Brands Hatch. This first Dunstall Dominator, which was to lead to many great machines, clocked 118mph unfaired. Theme variations followed and soon the idea of fitting Triumph twin engines by other builders followed, giving the Triton. Regardless of whether you regard them as a great motorcycle or the destruction of two perfectly good machines, the Triton still has many fans around the world, including ‘Mr Triton’ himself, former national and international racer Dave Degens. Tritons are still built today as are replica Featherbed frames, which Norton stopped making in 1970.

Desperate, AMC built a mass of hybrid machines in the Sixties, including the new Matchless G80 and G3, offered as the Norton ES2 MkII and Model 50 MkII, while the strong Atlas engine found its way into AJS/Matchless models. Despite all, AMC was on the skids by spring 1966, in debt by more than £2-million and, despite help from large American dealers and the kudos of the Dunstallised models, time was running out. The Official Receiver was called in. In September 1966, it was announced that Villiers, now part of E & HP Smith which, in turn, was part of Manganese Bronze Holdings, had acquired the manufacturing and distribution rights of AMC, but not the factories.

I lived through this and understood none of it at the time – and, in hindsight, still don’t grasp much of the small print. For Norton the result was a cut of model range to just the 650SS and 750cc Atlas. Much huff and puff followed and a new company, Norton Villiers, was formed. Despite all announcements and counter-announcements, behind the scenes a new machine was under development. Manganese Holdings boss Dennis Poore, a motoring enthusiast, wanted to help save the British motorcycle industry. In January 1967 he appointed ex-Rolls-Royce engineer Dr Stefan Bauer to head Norton Villiers’ new design team. Bauer the theorist with Bob Trigg the stylist and Bernard Hooper the practical engineer, didn’t hang about, with prototypes on the road by June and launch models ready by early autumn 1967.

I lived through this and understood none of it at the time – and, in hindsight, still don’t grasp much of the small print. For Norton the result was a cut of model range to just the 650SS and 750cc Atlas. Much huff and puff followed and a new company, Norton Villiers, was formed. Despite all announcements and counter-announcements, behind the scenes a new machine was under development. Manganese Holdings boss Dennis Poore, a motoring enthusiast, wanted to help save the British motorcycle industry. In January 1967 he appointed ex-Rolls-Royce engineer Dr Stefan Bauer to head Norton Villiers’ new design team. Bauer the theorist with Bob Trigg the stylist and Bernard Hooper the practical engineer, didn’t hang about, with prototypes on the road by June and launch models ready by early autumn 1967.

Named the Commando, it comprised an Atlas engine, AMC gearbox, rear swinging arm and wheel rubber-mounted as one unit in a frame they designed and styled. They patented the design under the banner Isolastic. Production soon moved from Woolwich to Thruxton and, for many, the Commando was to become as immortal as the International, Model 18 and Dominator had in earlier years.

The initial launch model 745cc Commando, available in a number of body guises including my favourite, the Fastback, was in production 1967-73 when the 829cc (850) range was launched, which continued until 1977.

In mid-1969 Peter Williams was appointed to head up the new Norton road racing department. The good times began to roll again in May 1970 when Peter Williams and Charlie Sanby won the Thruxton 500 Mile Race but then, owing to a fuel miscalculation, Williams just missed winning the 1970 Production TT. Still he made up for it winning the 1973 F750TT.

Many top-class racers rode Nortons again, including Phil Read, John Cooper, Dave Croxford, Mick Grant… and they got backing from John Player. Commando launch timing was good, a breath of fresh air for the world’s big bike market. Thanks to the efforts of former Greeves trials star Mike Jackson, Nortons sold well stateside. In a twist of bureaucracy, Norton Villiers were dragged down by the continued Meriden sit-in, their ambitious Cosworth Challenge failed and, in a cruel twist of fate, Peter Williams was seriously injured when his seat came adrift during racing.

Many top-class racers rode Nortons again, including Phil Read, John Cooper, Dave Croxford, Mick Grant… and they got backing from John Player. Commando launch timing was good, a breath of fresh air for the world’s big bike market. Thanks to the efforts of former Greeves trials star Mike Jackson, Nortons sold well stateside. In a twist of bureaucracy, Norton Villiers were dragged down by the continued Meriden sit-in, their ambitious Cosworth Challenge failed and, in a cruel twist of fate, Peter Williams was seriously injured when his seat came adrift during racing.

Then Tony Benn and the Labour Government backed the Meriden workers’ co-operative and withdrew Norton’s export guarantee facilities which, in effect, pulled the rug from under their feet, making the banks jittery. The last Commandos were built in 1977, but a new company, Norton Motors (1978) Ltd, was formed to keep the cash registers spinning selling parts, liquidated Commandos, mopeds… while the new project, a rotary twin, was under development.

Although out of the remit of our 25-year limit, the rotary engine was and still is an exciting concept and, for me, the limited edition Norton Classic released in late 1987 is the most attractive machine unveiled in the late Eighties. It’s perhaps fitting that the late Steve Hislop took a rotary to victory in the 1992 Senior TT. Various Norton projects have surfaced in the last few years; let’s hope if more are considered they are in the spirit of what was once the world’s greatest racing factory.

This brief guide began with the superlatives famous and unapproachable, which are also a fitting way to end. It took the might of the world’s largest maker, Honda, with an annual production figure far in excess of Norton’s entire production run, to surpass Norton’s enviable IoM TT record. Add to this the Bracebridge Street GP history, national racing around the world, clubmen sport, off-road, sprinting, sand racing… it’s little wonder Norton were considered for decades by their fans as the world’s greatest sporting factory.

This brief guide began with the superlatives famous and unapproachable, which are also a fitting way to end. It took the might of the world’s largest maker, Honda, with an annual production figure far in excess of Norton’s entire production run, to surpass Norton’s enviable IoM TT record. Add to this the Bracebridge Street GP history, national racing around the world, clubmen sport, off-road, sprinting, sand racing… it’s little wonder Norton were considered for decades by their fans as the world’s greatest sporting factory.

Enthusiasm abounds for all Nortons. There is good parts back-up for many post-WWII singles, along with a superb service for Dominators and Commandos. Specialist help is available for most models, from early side-valvers through to the rotary range.