Norton 1902 – UK

Often misused, the words unapproachable and famous apply 100 per cent to Norton. With around 250 GP and TT wins, beginning with Rem Fowler’s 1907 IoM TT twin-cylinder class victory and extending to Steve Hislop’s 1992 Senior TT win, success at Brooklands, most European and many worldwide short circuits, sand-racing, scrambling, trials, hillclimbs, sprinting… unapproachable is one of many apt superlatives.

Competition apart, fame also came through many models that became household names: Big Four, International, Dominator, 16H, Commando… and designs like the McCandless (featherbed) frame, cammy engines and their racer’s racer, the Manx.

Endless marque books, potted histories and Norton tales abound. It was an outstanding factory founded by an extraordinary man, and this guide can only scrape the surface.

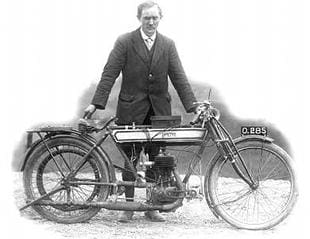

Born in 1869, James Lansdowne Norton’s life was shaped by religion, illness and middle-class family values. As an aspiring engineer, 12-year-old James built a working model upright steam boiler stationary engine. He became an apprenticed toolmaker on leaving school within Birmingham’s jewellery quarter and later became captivated by the blossoming cycle industry.

On advice, his parents sent him on a sea trip to New York to hasten convalescence following rheumatic fever. Norton’s continual ill-health later aged him, leading to the nickname Pa while he was still an active pre-WWI TT racer. During the voyage he became Salvationist and later joined the Birmingham Salvation Army Citadel, where later he met and then in 1898 married Sarah Saxelby. The year was of double importance as he also established the Norton Manufacturing Company in Birmingham to make cycle chains, then other cycle components and later cycles.

On advice, his parents sent him on a sea trip to New York to hasten convalescence following rheumatic fever. Norton’s continual ill-health later aged him, leading to the nickname Pa while he was still an active pre-WWI TT racer. During the voyage he became Salvationist and later joined the Birmingham Salvation Army Citadel, where later he met and then in 1898 married Sarah Saxelby. The year was of double importance as he also established the Norton Manufacturing Company in Birmingham to make cycle chains, then other cycle components and later cycles.

With a growing circle of contacts, including the rich business entrepreneur Charles Garrard who, in spring 1902, became the UK importer for the French motorised cycle engine unit Clement, James became involved with motorcycles.

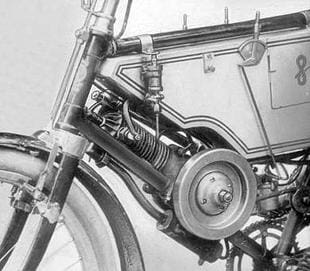

He began by building frames for Garrard, who sold complete machines (Clement-Garrard) and then, by late 1902, the 147cc Norton Energette with Clement engine. It was ideal for touring, racing, business and doctors, claimed Norton, similar to the Clement-Garrard, but with a longer wheelbase frame that became a hallmark of early Nortons.

As the motorised cycle craze gave way to motorcycles, Garrard’s motor bicycle business slowed, leading Norton in 1904 to concentrate on his own marque rather than build components for others.

Despite tiny sales levels, James continued to develop motorcycles and, by 1906, was advertising a seven-model range comprising direct belt-drive Peugeot-engined 330cc singles, 985cc V-twins, a two-speed Peugeot-powered forecar and a 198cc Clement-engined lightweight.

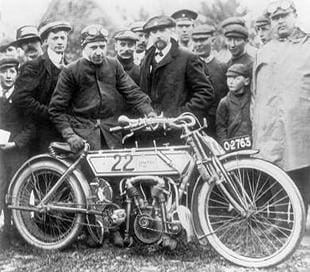

Following places in the 1906 Birmingham MCC members’ hill-climb at Rednal, Norton enjoyed their first speed win in the same event the following year. Rem Fowler, accompanied by James Norton as a pit attendant, then won the twin-cylinder class at the first TT races in 1907.

Despite endless stops to change plugs, repair punctures, wire on a broken mudguard stay and disentangle the front tyre after a burst, and a serious ‘off’ at a claimed 60mph, Fowler beat his nearest rival by more than 30 minutes and set the first TT lap record at 42.91mph. Norton were on their way, but not without a struggle.

At the 1907 Stanley Show, Norton shared a stand with Moto-Reve – for whom they were Midlands agents – to unveil their first Norton engine, a side-valve 475cc (82 x 90mm) single that was actively promoted through the Press mid-1908. In the 3 June Motor Cycle, Norton carried this testimonial, believed to be by Rem Fowler: “My success is due to my unapproachable Norton.”

At the 1907 Stanley Show, Norton shared a stand with Moto-Reve – for whom they were Midlands agents – to unveil their first Norton engine, a side-valve 475cc (82 x 90mm) single that was actively promoted through the Press mid-1908. In the 3 June Motor Cycle, Norton carried this testimonial, believed to be by Rem Fowler: “My success is due to my unapproachable Norton.”

Development continued and the range was regularly uprated, including development by Bob Newey – later of Levis – on a 4hp single, initially of 660cc; but the model displayed at the 1909 Stanley Show was of 633.7cc and 82 x 120mm dimensions. A year later it was given the immortal name ‘Big Four’ (4hp). The Motor Cycle were first to announce on 1 November 1910 the planned new 490cc Norton engine with the measurements 79 x 100mm, which remained until 1963, latterly only on the ES2 until it was reworked under AMC guidance.

The new engine made its Brooklands debut in March 1911, with EB Ware riding, and its TT debut later with both Pa Norton and Percy Brewster. However, on 6 July, Brewster first stamped Norton’s name on Brooklands, setting a new 351-500 class record at 73.57mph. Then, on 14 September, Hull Norton dealer Jack Emerson, with the throttle lever held against the stop, raced round the Weybridge track against a top-class field to win the 150-plus-mile Senior Brooklands TT (up to 500cc class) at a record 63.88mph, setting a 100-mile record at 64.22mph, then riding on to set a 200-mile record at 63.88mph before tyre problems scotched the 300-mile attempt. With a new tyre fitted, he rode back to Hull the following day.

While race success was on the rise, Norton factory finances were sliding. Pa’s illness meant he was often absent for months at a time, production slowed and, when he was there, he was more interested in race machine preparation and new model development than building motorcycles for sale. Money was of little interest to him. The company ended up under the auctioneer’s hammer, knocked down to successful Birmingham businessman RT (Bob) Shelley, who moved it to new premises at Sampson Street in August 1912 and wisely made Pa Norton joint-managing director along with Walter (Bill) Mansell to control the finances. Happily for Pa, this arrangement wasn’t all bad as Mansell was a Norton-owning enthusiast, trials rider and father of the later great trials exponent Dennis, who went on to secure so many trials wins for Norton in the inter-war period.

Motorcycle development, especially on the performance front, took another twist. Bob Shelley’s brother-in-law was the young but experienced rider/tuner Daniel (DR Wizard) O’Donovan. A Brooklands habituee who started his racing career on a Singer, he finished fourth in the 1913 Junior TT for NSU and then immediately switched to Norton, building a record-breaking sprinter believed to be from the part-dismantled remains of Jack Emerson’s machine. Later named Old Miracle, it gained 112 records either side of WWI with ‘Wizard’ hanging on during a particularly rough period for the Brooklands track’s concrete surface. This machine inspired the BS (Brooklands Special) and BRS (Brooklands Racing Special) 490cc side-valve sports models which are so sought-after today.

Motorcycle development, especially on the performance front, took another twist. Bob Shelley’s brother-in-law was the young but experienced rider/tuner Daniel (DR Wizard) O’Donovan. A Brooklands habituee who started his racing career on a Singer, he finished fourth in the 1913 Junior TT for NSU and then immediately switched to Norton, building a record-breaking sprinter believed to be from the part-dismantled remains of Jack Emerson’s machine. Later named Old Miracle, it gained 112 records either side of WWI with ‘Wizard’ hanging on during a particularly rough period for the Brooklands track’s concrete surface. This machine inspired the BS (Brooklands Special) and BRS (Brooklands Racing Special) 490cc side-valve sports models which are so sought-after today.

Each carried a certificate of its performance awarded by O’Donovan and the factory after testing at Brooklands. Many engines, it is claimed, were installed in Old Miracle’s rolling chassis for testing. This grand machine, bearing the registration AOK 200, survives as part of the National Motor Museum collection at Beaulieu and is given the occasional airing by personalities in the Pioneer Run and at racing parades.

As the tiny Birmingham factory wasn’t invited to trials for military suitability and orders in 1912, they continued to refine and redesign their range into the early war years. Norton’s daughter, Ethel, was responsible for the famous Norton logo that first appeared in 1914, while countershaft gearboxes and all-chain drive appeared for the first time on the Big Four and selected 490cc models for the 1915 season, using Nottingham-made Sturmey Archer three-speed boxes. Chain-cum-belt became an option, too, but the BS, BRS and TT models retained direct belt drive. Norton speculatively announced a military model in July 1916 – in effect a Model 16 in colonial trim with generous-for-the-period 6.25in ground clearance. While the UK military were already suited, the Russian forces, who’d already bought other British models, liked what they saw and placed orders for the machine, but with the 633cc Big Four engine instead of the 490cc unit. It’s doubtful any of the light grey all-chain-drive singles were ever delivered, owing to the Russian Revolution, although one batch may just have slipped though, leaving Norton with a good stock of machines to revamp for the civilian markets after the war.

Wisely, James had foreseen that the war’s end would lead to civilian motorcycle demands outstripping supply, resultant high prices and profits, after which there would be a glut, sales would slump and prices tumble. Norton did take time to be ready, thanks in part to delays of buying the undelivered Russian order models back from the Government. It was a lucrative idea. However, by mid-1919, Norton were able to advertise the year’s full range for the first time comprising Model 1: chain-drive three-speed Big 4; Model 16: chain-drive three-speed 31⁄2hp TT; Model 9: TT belt-drive single-speeder; Model 8: BRS; and Model 7: BS.

Wisely, James had foreseen that the war’s end would lead to civilian motorcycle demands outstripping supply, resultant high prices and profits, after which there would be a glut, sales would slump and prices tumble. Norton did take time to be ready, thanks in part to delays of buying the undelivered Russian order models back from the Government. It was a lucrative idea. However, by mid-1919, Norton were able to advertise the year’s full range for the first time comprising Model 1: chain-drive three-speed Big 4; Model 16: chain-drive three-speed 31⁄2hp TT; Model 9: TT belt-drive single-speeder; Model 8: BRS; and Model 7: BS.

As roadsters began rolling through the factory gates, sport rumbled into life again, industrial action reared its head and Norton moved premises again. Alexander Lindsay kicked off with a gold in the 1919 ACU six-day trial, industrial action brought much of British Industry to a standstill by early 1920 – the period when Norton moved to one of motorcycling’s landmark addresses at Bracebridge Street, Birmingham – and in the summer Duggie Brown took second in the Senior TT behind Tommy de la Hay’s Sunbeam. Later, renowned writer and commentator Graham Walker, part of the Norton team who was to manage the private entries freeing O’Donovan for the factory boys, finished 13th in his first Island ride.

Rumours began regarding Norton’s development of an ohv model. The gossip had foundation as, during the winter of 1921-22, that was exactly the case. But Pa Norton found time, or needed the convalescence, to take a 3000-mile trip around South Africa aboard his favourite Big Four. He was back in time to see Rex Judd on 17 March 1922 scorch into the record books aboard the new, but still under development, 490 ohv single. He completed the flying kilometre in 98.76mph (a British record) and the two-way flying kilometre in 89.92mph (a world record).

Mixed success greeted the development models: Cawthorne rode the only ohv in the year’s Senior TT to retire, and ohv Nortons gained places on the Continent and their first major win at the Ulster GP, ridden by Hubert Hassell. Victor Horsman joined Rex Judd on a 19-record spree at Brooklands with a Wizard O’Donovan-prepared machine and the roadster version 490cc (79 x 100mm) ohv Norton was unveiled at the 1922 Paris show and later christened the Model 18.

Mixed success greeted the development models: Cawthorne rode the only ohv in the year’s Senior TT to retire, and ohv Nortons gained places on the Continent and their first major win at the Ulster GP, ridden by Hubert Hassell. Victor Horsman joined Rex Judd on a 19-record spree at Brooklands with a Wizard O’Donovan-prepared machine and the roadster version 490cc (79 x 100mm) ohv Norton was unveiled at the 1922 Paris show and later christened the Model 18.

Road racing continued apace in 1923, but not without trouble in the camp – led by Graham Walker, who risked Pa Norton’s wrath to fit Webb front forks to his racers instead of the factory’s favoured Druid forks. Walker entered as a privateer but, by race day, all bar one of the ‘works models’ had Webbs. Graeme Black finished second in the Senior with Walker fourth. Walker was second in the first sidecar TT with George Tucker third, trailing Freddie Dixon’s banking Douglas sidecar, which had taken the lead after Harry Langman’s Scott crashed at Braddan Bridge.

On the Brooklands/record-breaking front, Judd moved to Douglas. His place under O’Donovan’s wing was taken by Bert Denly. While solo places were the best they’d manage during the main Continental classics, George Tucker took two wins (600cc and 1000cc) in the summer’s Belgian GP for sidecars and, significantly, in the final GP of the year, the Ulsterman Joe Craig won the 600cc class on a borrowed Norton, his first race on the marque.

Soon after, Nortons scooped the Maudes Trophy on a ‘standard’ Model 18; its assembly monitored by an ACU official. Riding in shifts, Bert Denly, Nigel Spring and Wizard O’Donovan scooped 18 world records in 12 hours at Brooklands. The Model 18 was exactly like the man in the street could buy and you, if lucky enough, could own and ride today. The motorcycling world was impressed, very impressed, but the best was yet to come.

The winter of 1923/24 was a time of change for Norton, and a rethink by board chairman Bob Shelley, who’d long believed Nortons were so good they could win anything regardless of the rider. Lonnie Lamb of Castrol put him right, threatening to limit support if Shelley’s riders weren’t good enough. Then competitions manager Graham Walker left for Sunbeam.

Chastised, Shelley instructed Bill Mansell to sign a leading rider for the coming 1924 season, finally securing Southampton motorcycle shop owner Alec Bennett. Walter Moore was signed as technical man in the spring and soon improved Norton braking and oiling. Sidecar driver George Tucker, with Moore aboard – to experience the engine under race conditions – took Norton’s first TT win since 1907. Then Bennett, who’d spared his engine in the early stages, cruised to the Senior win after mishaps relegated Freddie Dixon to third.

During the year Norton added to their glory, with wins in the Spanish, Belgian, Ulster and French GPs, plus many other National and International speed events. Again they took the Maudes Trophy. Suddenly they moved into the top league of International racing teams, where they remained for the next three decades. Tragically Pa Norton, who’d been ill for much of his life, was slowly losing his battle against cancer, dying on 21 April 1925. Norton had a quiet year in 1925, and then signed Irishman Stanley Woods who won the 1926 Senior TT.

During the year Norton added to their glory, with wins in the Spanish, Belgian, Ulster and French GPs, plus many other National and International speed events. Again they took the Maudes Trophy. Suddenly they moved into the top league of International racing teams, where they remained for the next three decades. Tragically Pa Norton, who’d been ill for much of his life, was slowly losing his battle against cancer, dying on 21 April 1925. Norton had a quiet year in 1925, and then signed Irishman Stanley Woods who won the 1926 Senior TT.

But all was not well on the domestic front. They were forced to finance their own HP scheme – a risky practice – and drop model prices further. Bob Shelley discovered he too was terminally ill, and the company was restructured as Norton Motors (1926) Ltd to separate it from Shelley’s other holdings. While the pushrod 490cc Norton was enjoying continuing success, Moore noted the rise of the ohc engine in racing. Although at first developing no more power than comparable ohv jobs, the cammy units proved more durable at racing speeds, especially over long distances. Walter Moore knew he had to do something after watching Alec Bennett win the 1926 Junior TT with a cammy Velocette. All he had to do was convince the Norton board!

History tells us that in the winter of 1926/27 Moore designed the engine in his spare time and also a new cradle frame. Moore, the designer and Stanley Woods the mechanic, tester and racer, related conflicting tales of the engine’s progress from drawing board to TT winner (Alec Bennett). Woods later took the Dutch, Swiss and Belgian GPs. A crash dropped Woods to second in the German and claimed engine problems sidelined Joe Craig and relegated Woods to third in the Ulster GP. Norton had enjoyed a good year, underlined by Bert Denly’s achievement as the first 500 to crack the 100mph record for the hour at Montlhery on a pushrod model. Denly also broke the five-kilometre and five-mile records.

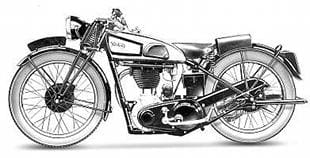

Quite what Norton’s ambitions had been for the cammy model, when Bennett and Woods pushed off for the 1927 Senior TT, is unknown, but, by the autumn, a road-going ohc 490, installed into a cradle frame, was on offer to the public as the CS1, along with what was in effect a cradle-framed Model 18, coded the ES2, both with saddle tanks. Another Norton first.

Although a good first effort, the CS1 had its problems. Some real, some perceived. Without doubt it chipped teeth off the bevel drive under prolonged flat out race work and the Sturmey Archer clutch proved weak. Stanley Woods stated this fault cost him the 1927 Senior TT. Other problems included cylinder head overheating and oiling doubts, again under racing conditions. Despite all, for the man in the street who could afford the CS1, it was a breath of fresh air.

Although a good first effort, the CS1 had its problems. Some real, some perceived. Without doubt it chipped teeth off the bevel drive under prolonged flat out race work and the Sturmey Archer clutch proved weak. Stanley Woods stated this fault cost him the 1927 Senior TT. Other problems included cylinder head overheating and oiling doubts, again under racing conditions. Despite all, for the man in the street who could afford the CS1, it was a breath of fresh air.

Unnoticed by some, another Norton star in the making – Tim Hunt – played his first card in September 1927, winning the Amateur TT on a Model 18. For the next couple of years the works ohc Nortons enjoyed mixed success. Highlights included young Dennis Mansell’s win in his first Victory trial (1928) with his CS1 outfit. And, as if to underline the model’s versatility, Tim Hunt again took the Amateur TT on a CS1, the same machine he’d ridden earlier in the year in the Scottish Six Days Trial.

Norton added, for the first time since pre-WWI days, an under 500cc machine to their fold, the 350 ohc model, which first raced in the 1928 Junior TT – without success – and went on sale to the public as the CJ in February 1929, almost immediately joined by the ohv 350cc JE.

Mixed success continued to dog the cammy racers, leading to a rift between Mansell senior and Moore, with Mansell threatening action if Norton didn’t win and Moore blaming rider abuse and poor pistons. The main fault, Joe Craig later claimed, was the revised cylinder head design Moore had introduced after the CS1’s initial racing success. Moore went to NSU and Craig rejoined Norton, going back to the original cylinder head design for the 1929 UGP. They didn’t win, but at least they didn’t overheat. Woods was second with Tim Hunt – now a Norton works rider – third. Craig’s diagnosis proved right weeks later, as Hunt scorched to a blinding win in the 500cc Spanish GP and in a rare road race outing young Mansell took the sidecar class. Joe Craig and chief draughtsman Arthur Carroll set to designing a new ohc Norton engine; work focused on the top end. Who was responsible for the lion’s share of ideas is unclear, with some claiming it was Craig’s design, but history tells us the unit became known as the Carroll engine.

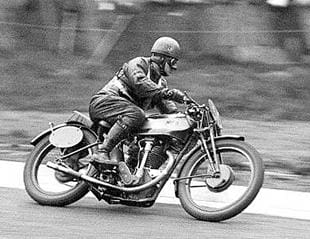

The reworked engine made the 350/500 works Nortons’ ‘unapproachable.’ A run of TT Junior/Senior doubles from 1931-37 was spoilt only by ex-Norton star Stanley Woods’ V-twin Moto Guzzi win in the 1935 Senior. The IoM TT winning Norton riders in the Thirties were Harold Daniel, Freddie Frith, Jimmy Guthrie, Percy (Tim) Hunt and Stanley Woods. Other renowned works riders included Walter Rusk, Jimmy Simpson and Crasher White.

The reworked engine made the 350/500 works Nortons’ ‘unapproachable.’ A run of TT Junior/Senior doubles from 1931-37 was spoilt only by ex-Norton star Stanley Woods’ V-twin Moto Guzzi win in the 1935 Senior. The IoM TT winning Norton riders in the Thirties were Harold Daniel, Freddie Frith, Jimmy Guthrie, Percy (Tim) Hunt and Stanley Woods. Other renowned works riders included Walter Rusk, Jimmy Simpson and Crasher White.

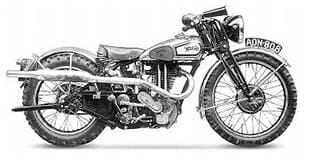

Despite the initial success of the Carroll engine, the general public found it initially near impossible to buy the model over the counter, many regarding the new machine as not truly on sale until late 1931. Although Norton displayed the model, and tied a price tag to it the new cammy Norton was in unpublicised factory words reserved for ‘riders/customers of ability’. But this was to change, in September 1931, when the race-bred cammies were joined by the International ohc 350/500 models, a superb compromise between racer and roadster.

While all this camshaft work was going on, the side-valve and pushrod models moved down the Norton pecking order. The once sporting side-valve 16H gained softer cams and a workhorse role alongside the Big 4, while the ohv models led by the cradle framed ES2 and open framed Model 18 became the fast tourer for the rider with taste. Many privateers also campaigned them.

Although not always to the forefront of Norton advertising, the company enjoyed regular off-road success through the Thirties led by Dennis Mansell, Jack Williams, Vic Brittain and Harold Flook. But as WWII approached, Norton suffered tragedy and disappointment. Jimmy Guthrie died in an accident at Sachsenring. An incident still surrounded by mystery, myths and accusations. The multi-cylinder Gileras and twin-cylinder BMWs were beginning to challenge Norton’s Continental race-track stranglehold, while Woods won the 1938 and 1939 Junior TTs for rivals Velocette and BMW relegated Norton to third in the 1939 Senior.

On the home front, things looked up as Dennis Mansell negotiated terms for the sales of the military 16H and Big 4 models, and continued in this liaison role through the war. Unsure, like many, how long the war would last, Norton planned 1940 models which were similar to the previous year’s range and included many favourites like the International, CS1, CJ and ES2 along with established old stagers including the 16H, Model 18 and 19 (588cc until 1933 and 597cc after) and Big 4. From 1935 Norton stated any model could be supplied in trials trim for an extra £5. After the war, Norton publicity claimed Bracebridge Street had supplied over 100,000 motorcycles to the allied war effort. A significant contribution, which almost overshadows another significant effort, that of Jackie Moore who designed the Roadholder oil-damped telescopic front fork. Norton patented this design in January 1944 and from September 1946 it was standard fitment on all models.

NB: Norton’s history has been split into two parts. Click here for post-war Norton history.