OCMA 1953-c1960s Italy

Well made two and four-strokes from 48-175cc. Typically Italian lightweight motorcycles, the sports models perform well too. Like many Italian machines, exports were limited but examples now find their way out of Italy. Different, but spares are difficult.

OD 1927-35 (c1950s) Germany

Assembly/manufacture began in Dresden with a range of MAG-engined singles and V-twins designed, developed and produced by Willy Ostner. A 996cc MAG-powered heavyweight was intended for sidecar work and soon gained a reverse gear. A large racing machine with 55hp ohv 980cc and 998cc V-twin engines was soon in small-volume production and as an outfit ridden to national success by Arno Zaspel. Later, an ohv 497cc MAG D50-engined racer joined the range.

In the early Thirties, Willy Ostner added a new V-twin to his stable using the Bert Le Vack-designed 846cc sidevalve MAG engine. Ostner also developed a cast alloy lightweight frame in which he installed 198cc/246cc single-cylinder Bark two-stroke engines. During the early Thirties, OD began making lightweight two-stroke threewheel delivery vehicles that became popular with German shopkeepers, smallholders and tradesfolk. In 1935 motorcycle production ended but manufacture of the often Ilo-powered trade trikes continued until WWII and then after the war ended.

OEC 1901-54 UK

OEC 1901-54 UK

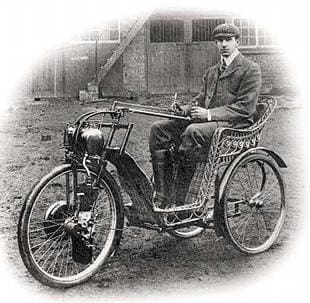

Cruelly but maybe accurately dubbed the Odd Engineering Company, Oddly Engineered Contraptions and similar, the Osborn Engineering Company began making motorcycles in 1901, like so many others, by installing Minerva kits in sturdy cycles.

As the long-term custodian/rider of a 1924 550cc OEC Blackburne, I confirm OECs are at times odd – mine’s pretty conventional by OEC standards – and crude. Endless spacers between engine plates ensure the chain line of my example is true. Well, near-true! But, after 38 years together, she still gives me immense pleasure.

Despite inter-war OEC brochures claiming the company was established in 1915, they’d made a few Minervaengined motorcycles along with some motorised invalid carriages since 1901. Then the firm, founded by former racing cyclist Frederick Osborn appears to have dropped out of the motorcycle world until after WWI. However, even this observation is not without its problems as OEC were involved business-wise with engine-makers Blackburne since 1914 and, it’s believed, built or at least part-built the Blackburne motorcycle.

By 1920 Frederick was joined in business by son John and engineer Fred Wood at their then Lees Lane, Gosport, premises. Blackburne, in common with many other leading engine-makers, realised it wasn’t a good idea to build motorcycles in competition with those manufacturing customers who were buying their engines. OEC took over marketing of the Blackburne, rebranding it the OEC-Blackburne with the slogan ‘The machine that runs like a car’.

Using the single-cylinder Blackburne as a stepping-stone, OEC soon developed a range of 250cc-550cc side-valve singles, lusty V-twins and a sporting ohv 350, all with Blackburne engines. While this development was under way Frederick, John and Fred – men who had no real grasp of the words conventional, orthodox or normal – revealed their love of the unorthodox to the motorcycling public for the first time.

In common with BSA, Rex-Acme et al, OEC unveiled a 1000cc, side-valve, V-twin, Blackburne-powered motorcycle combination taxi. So far so good, but OEC went one better, replacing the conventional handlebars with a steering wheel and some complicated engineering to make the plot work.

All a taster of what was to come, including ultra-highframed motorcycles and ones with huge tyres for colonial work, part-tracked motorcycles, fully enclosed engines and, of course, their famed patented duplex steering, designed by John Osborn.

As the Twenties rolled by, OEC began to install other proprietary engines in their frames and even guaranteed to fit any engine to any one of their frames at a customer’s behest. Their relationship with Blackburne cooled and the engine-maker’s name was dropped from the brand logo that became OEC, later coining the slogan ‘The modern motorcycle’. By 1926 they were building their own 350cc ohc single called the Atlanta and in 1927 came duplex steering, duplex frames and their own plunger-type rear suspension. In 1929 speedway models joined the range.

In the early Thirties OEC struggled financially and production stopped. With cash from leading dealers, Glanfield Lawrence Ltd, motorcycle manufacture restarted at Atlanta Works, Highbury Street, Portsmouth. The range was almost as before although, by the late Thirties, Matchless power had replaced JAP. Happily John Osborn and Fred Wood hadn’t forgotten the bizarre!

During 1934-36 the Whitwood Monocar, with retractable stabiliser wheels for parking and slow speed work, was offered with an option of engines from 250cc Villiers to 1000cc V-twin JAP units. Then there was the Atlanta Duo, an ultra-low motorcycle with its engine mounted horizontally to keep its centre of gravity low. Osborn and Wood claimed it was impossible to fall off this model. As a sideline, OEC built specialist motorcycles to order, including motorcycle outfits equipped to determine road surface condition for the Road Research Laboratory.

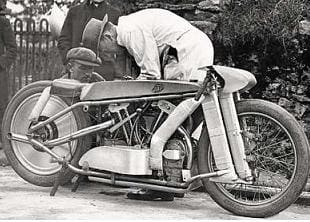

Few think of OEC as a racing factory, although they had their moments, including at Brooklands, and they held a number of world speed records including the outright record by Claude Temple in 1926 and Joe Wright in 1930. However they, along with others, ended with red faces after displaying the world record-winning OEC at the London Show in autumn 1930. Owing to machine problems with his OEC Wright had, in fact, gained the record for a second time in the year with his secondstring motorcycle, a Zenith!

Although not recognised as a ‘military’ company like BSA, Norton or Matchless, OEC supplied small numbers of 342cc Villiers-engined models to the RAF during the mid/late Twenties. To Army request they also built threewheeled solo motorcycles with duplex steering and two small in-line wheels replacing the rear wheel. Although the prototypes survived military testing, they didn’t handle as the Army had hoped and the idea was dropped.

At the outbreak of WWII OEC were given non-motorcycle military work but not for long as their Atlanta Works was levelled during a German bombing sortie on the harbour, along with neighbouring properties in the older part of Portsmouth. After the war OEC motorcycle production restarted in an old Stamshaw Road, Portsmouth, workshop that was again named Atlanta Works. They began with a range of smart on and off-road Villiers-engined lightweights and once again 500cc JAP-engined speedway machines. A 250cc Brockhouse-engined model joined the range but, by 1954, motorcycle production ended, leaving OEC to soldier on for a few more years making tubular steel office/school-style furniture.

Cycle parts availability falls into the category of ‘make your own’, although the occasional fuel tank and the like turns up at autojumbles. Parts can be found for many of the pre-WWII proprietary engines used with some hunting and there’s good availability for post-WWII Villiers engine spares.

Note: OEC, in conjunction with specialist builders/tuners, offered a range of sporting singles and twins during the inter-war period aimed at the fast road or racing rider. For example, there was the OEC Temple available through Claude Temple, 11 Edgeware Road, Marble Arch, London, whose 1927 range comprised 496cc ohv single, 496cc ohc single and 996cc V-twin.

Ogar 1934-50 Czechoslovakia

Prague-based manufacturer with accessory trade links that, for some years, built an attractive sporting 246cc two-stroke single designed by Frantisek Bartuska. Water-cooled variants were made for road racing and off-road sport. Following the growing speedway interest in Eastern Europe, Ogar built small batches of 500cc single-cylinder speedway racers, first with JAP engines and later their own ohv unit.

After WWII Ogar was nationalised. First new model was a 348cc unit ohc single with telescopic front fork and plunger rear suspension designed by Vaclav Sklena, built only in small batches. Then came a smart utility 346cc parallel twin-cylinder two-stroke, not unlike the Jawa 246cc twin-cylinder two-stroke, which is not surprising as Ogar was absorbed by Jawa c1947. The Ogar logo was used on selected models until 1950. Very occasionally an Ogar-badged 346cc twin appears on the Continental autojumble circuit.

OK Supreme (OK) 1899-1939 (1946) UK

OK Supreme (OK) 1899-1939 (1946) UK

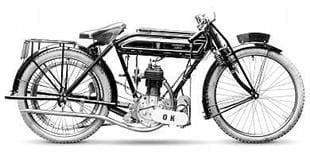

Founded by Ernest (Ernie) Humphries and Frederick Dawes in 1882 as Humphries and Dawes to manufacture cycle fittings and later complete cycles. The partners were among the UK pioneers of motorcycle development, making machines using first De Dion, then Minerva, later JAP, then air-cooled Precision engines and units with water-cooled Greens cylinders, all at their tiny Lancaster Street, Birmingham premises. The machines were marketed as OK. Despite these forays, Humphries and Dawes didn’t become serious players in the production stakes until 1911.

A racing fan, Ernie Humphries, often known as ‘Black Ernie’ thanks to his ferocious temper, entered EV Pratt in the 1912 IoM Junior TT aboard a Precision-engined OK with Sturmey Archer three-speed hub gear. Pratt finished ninth at 28.51mph after five-and-a-quarter hours in the saddle. Slow but OK – OK Supreme’s long association with racing had begun.

With the business apparently thriving, they moved to larger premises at York Road, Hall Green, Birmingham, in 1914. Motorcycle production stopped as WWI started, the firm machining armaments parts. Cycle manufacture restarted as the war ended but Humphries and Dawes waited until 1920 before reintroducing motorcycles, OK Juniors powered by either 292cc Union or 269cc Villiers two-stroke engines. They were excellent, worthy machines but not the racers Black Ernie yearned for.

Salvation came in 1922 for Ernie when Blackburne introduced their neat, powerful, 250cc ohv unit, and three OK-Blackburnes were entered for the year’s TT, Belgian and French GPs ridden by testers Neville Hall and Charlie North and factory apprentice Walter Handley. North and Hall finished sixth and seventh in the Lightweight TT while Handley in his Island debut, sensationally raised the lap record from 46 to 51mph from a standing start before retiring. Handley later finished second in the Belgian GP.

A year later Handley again broke the lap record from a standing start then crashed heavily before finishing eighth. Black Ernie lived up to his name and publicly let fly at young Walter, who promptly parted company for Rex Acme and three TT wins, including the double in 1925 and another for Rudge – and, of course, his major part in the naming of the BSA Gold Star following his Brooklands success in 1937. Walter lost his life in a WWII flying accident.

After briefly hiring Stanley Woods and further failures, works OKs didn’t race again until 1927. Instead Humphries and Dawes, under Ernie’s guidance, concentrated on building a reputation for good quality machines, moving away from two-stroke engines in favour of JAP, Bradshaw and occasionally Blackburne four-stroke units.

Relationships between Humphries and Dawes were always strained, Dawes’ longing for mass-produced cheap motorcycles against Ernie’s desire for quality and speed leading to a final split. Dawes went on to establish his famed cycle factory, while Ernie re-established the motorcycle business.

The Hall Green factory was sold to Velocette, which were desperate to move from their smaller Six Ways, Aston premises, and their cash financed the split. Ernie renamed his firm OK-Supreme with son John as joint works manager and daughters Alie financial controller and Freida sales manager. Although privateer, OKs had continued racing in the Island after 1923, possibly with limited factory help, OK-Supreme returned in 1927 with a Lightweight third for CT Ashby in 1927 and an awesome win by over 17 minutes in the 1928 Lightweight for Frank Longman, after a high-speed battle with Walter Handley’s Rex-Acme which finally expired. It was OK-Supreme’s only IoM TT win but they enjoyed many places, including 1930 Lightweight second and third for Paddy (CW) Johnston and former Royal Enfield rider CS Barrow.

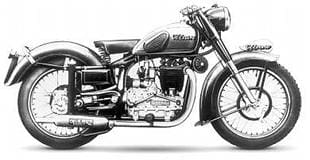

Moving into the Thirties, Black Ernie again showed his colours with a desire for exclusivity, first with the sloping engine 248cc ohc oversquare Model A, with a bevel driven face cam and transverse rockers to control the valve openings.

It was later given the name the Lighthouse, as it had a clear window at the top of the camshaft cover, enabling owners to check oil flow. It’s claimed this engine was offered in a 350cc form but I’ve never seen one.

In 1934 the Lighthouse was replaced by a more conventional sohc unit in both 248cc and 346cc capacities. Offered in various specifications and raced, too, these engines continued until WWII. Both ohc concepts were created by independent designers George Jones and Ray Mason and built for Humphries by Williams and Jones of Gloucester.

During the Thirties, in common with many rival small to medium-sized motorcycle factories, OK Supreme believed an extensive range was their way to survival in the depression. Relying predominately on JAP and later AMC power, as well as their own units, they built sportsters, sloggers, tourers and even briefly tried an ultra-lightweight with the 148cc side-valve JAP unit in 1932, although it’s doubtful if many of this Model P were ever made. While OK Supreme weren’t the type of company to make serious money, they kept the wolf from the door and the Humphries family earned their daily bread until, in the late Thirties, it all went horribly wrong.

In 1910 a federation of cycle, motorcycle and proprietary parts makers established the British Motor Cycle and Cycle Manufacturers and Traders’ Union. As far as the man in the street was concerned, the union was a jovial body that organised the annual Motor Cycle Show. True, they were responsible for the show, but jovial they weren’t. From 1919 to 1952, the union was headed by a solicitor, Major Henry Richard Watling, who has been described in the past as the industry’s hard man. Watling established a second body, the Cycle Trade Union (CTU). Virtually all cycle, motorcycle and proprietary parts manufacturers were members of both bodies and, bizarrely, the CTU was registered with the Government as a trade union, despite representing the bosses not the workers.

The union set minimum prices, prevented its members selling motorcycles to non-approved traders and, conversely, prevented approved traders taking machines from non-approved manufacturers. It established minimum shop stock levels and its inspectors – or often the Major himself – regularly checked premises in surprise visits for cleanliness, display standards and any flouting of the union’s extensive regulations. Watling ruled supreme. Dealers and manufacturers who flouted the Union’s rules were fined, temporarily suspended or, even worse, put on the Stop List which, in effect, ended their mainstream trade.

London dealers Pride and Clarke were on the Stop List for much of the Thirties for undercutting prices and offering too-generous deals and hire purchase agreements. Another who tried to operate outside the union’s rules was Ernie Humphries, who tried to increase his trade by supplying machines to non-approved dealers and by undercutting prices with special terms and discounts – practices Watling banned.

Rapidly selected proprietary parts makers, including Dunlop, ended supply of parts to OK Supreme, no unionapproved dealers would take their products and lucrative Government armament contracts were put on hold. As punishment, Black Ernie had to publicly apologise by placing an advert in the Motor Cycle and Cycle Trader magazine and pay a very hefty fine. It’s claimed he sold his substantial house to finance this error of his ways.

While Watling and the union might seem to us dictatorial, it is worth remembering that, while Watling was in charge of the union, our British motorcycle industry survived the depression and at times thrived, only for the wheel to fall off some years after he retired.

Although also hit by the decline of JAP, OK Supreme continued to build worthy machines at a competitive price for the customer who wanted good value for money in terms of quality and specification, but they were not always the cheapest. At the outbreak of WWII, John Humphries signed up for the duration, leaving Ernie to sell the firm’s premises. After the war, John restarted production with alcohol-fuelled grass track racers but then mysteriously died following a fall from a hotel bedroom window. Ernie died soon after and OK Supreme were gone.

Ollearo 1923-52 Italy

Ollearo 1923-52 Italy

Turin-based factory founded by Neftali Ollearo who, for an Italian, must have been the exception who proved the rule. He appears to have had no interest in racing! Production began with a basic 130cc two-stroke singlecylinder lightweight soon followed by a range of up to 500cc ohv singles built in unit with the gearbox. Twostrokes continued, too, some with separate gearboxes. In 1934 a strange car was launched comprising a threewheeled motorcycle clad in lightweight, car-type bodywork. Ollearo’s familiar range of serviceable lightweights and worthy larger tourers continued after WWII, joined by a 45cc two-stroke clip-on cycle attachment.