Rabeneick 1933-63 Germany

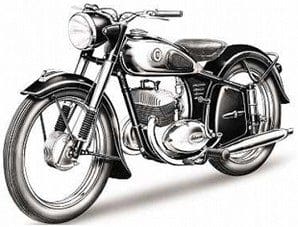

Bielefeld company founded by August Rabeneick to make ultra lightweights and autocycle type machines with bought in two-stroke engines including Sachs. AfterWWII its range was expanded to include 98-247cc two-stroke singles using Ilo and Sachs power. Briefly in 1951 Rabeneick produced larger horizontally opposed flat twin four-strokes and an Ilo powered two-stroke parallel twin; the F250/2, was built 1951-57.

A 250cc four-stroke shaft drive Swiss Universal engined single debuted at the 1953 Frankfurt Show but was too expensive to make any real impact on the German buying public. Hit badly by the German slump in motorcycle sales in the middle to late Fifties Rabeneick then concentrated on a moped and ultra-lightweight range after 1958.

In the new range, Rabeneick’s largest machine was the LM100/4 with Sachs 98cc power, while mopeds included the Saxonette, Binetta Super-4 (four-speed), Binetta Super-5 and R50 scooter. In 1963 Rabeneick became part of the Zweirand-Union and by the Seventies its plant was turning out Fitchel and Sachs automotive parts.

Mechanical spares for many Ilo and Sachs engines are readily available in Germany but Rabeneick cycle parts are scarce.

Radco 1913-32, c1955 UK

Radco 1913-32, c1955 UK

Birmingham maker of 211 and later up to 247cc two-stroke singles with their own distinctive engines, sporting outside flywheels. Models on offer included direct-drive run-and-jump jobs. During the Twenties, Radco developed its own ohv 247cc engine and went on to fit a range of Villiers two-stroke engines and up to 500cc JAP side-valve and ohv singles. Top models included the 490cc ohv JAP-engined Sport and Super Sport.

The recession killed off Radco, although the controlling engineering company remained in business. During the Fifties Radco developed a 49cc moped but other than prototypes it never went into series production.

Radior 1904-55 France

Established at Bourg in the pioneer period, Radior began with pedal-start models using Zurcher and Peugeot power. Keeping with the times, pedals were dropped in favour of gearboxes and kick starts. Restarting after WWI, Radior added typical French pedal-start two-stroke direct-drive velomotors. Basic, cheap and rugged they were though, Radior went one better than many rivals, offering velomotors with electric lighting when acetylene was still the norm for lightweights.

Radior often used Nervor engines for the lightweights, made in the same works at 9 Avenue de Paris, Bourg as the Radior and may have been part of the same company. Often Chaise, Antoine or JAP units were employed for larger models, including single and twin-port ohv 490c JAP powered models with JAP cast on the crankcase but Radior on the timing cover.

Production restarted after WWII with a range of up to 250cc two and four-stroke models using Nervor and French-built AMC engines. In the early 1950s, a tie up with the German NSU factory led to Radior marketing 49cc NSU Quickly-powered mopeds and 98/125cc NSU-engined lightweights. Radior and Nervor ceased production at the same time in 1955 although some sources indicate they may have continued to market NSU models for some time.

Raleigh 1899-1905, 1919-33 and 1958-71 UK

Raleigh 1899-1905, 1919-33 and 1958-71 UK

Famous, respected Nottingham cycle maker that marketed cycles, motorcycles and later mopeds as Raleigh. Became part of the Tube Investments (TI) group. Cycle components, motorcycle hub gears/clutches, countershaft gearboxes and engines were supplied to rival makers branded as Sturmey Archer.

Raleigh entered motorcycle production with an early Werner-like machine, in effect a Raleigh cycle with Schwann engine clipped over the front wheel, which it drove directly by twisted leather belt. Probably few were made but in 1903 at the Crystal Palace Show, Raleigh unveiled an advanced 3hp model with engine shaft clutch, countershaft, rear wheel sprocket shock absorber and twistgrip carburettor control. Also on display was a smaller 2hp model, with options of chain or belt-drive and the 3hp Raleighette forecar.

Despite claims of impressive production figures, sales were clearly too slow for Raleigh. There was nothing wrong with the product, simply those amongst the public with £40-50 to spend on an unknown quantity were few and far between. And there were plenty of rivals in the same marketplace.

In an attempt to secure more sales, Raleigh enlarged the engine size of its top model to 500cc (31⁄2 hp) for the 1905 season. Clearly a do or die move, as by April 1905 flagship Raleighs were on offer at 20 per cent off, then a month later advertised at just £25 with the marketing man’s inducement of, ‘No more at this price when these are sold’. Nor was there! Raleigh wasn’t run under sentimental family ownership, but by big business with a boardroom of directors. Motorcycles weren’t selling fast enough for the enterprise to worry the profit column, so they were gone. Until 1919 that is when the board judged the time was right to really set the cash registers spinning.

Although many history books tell us Raleigh returned to motorcycle manufacture in 1919, the board had been planning their comeback for some time. In truth, it’d never really been away as the company developed hub gears and clutches for motorcycles and later its superb three-speed gearbox which served so well during WWI, especially mounted to the DRs ‘Trusty’ Triumph Model H.

Like Raleigh cycles and motorcycles these hub gears and gearboxes were also produced in Nottingham but were marketed under the Sturmey Archer banner. A neat ploy allowing Raleigh to break the first rule of the proprietary parts makers, ‘not to build or market complete machines in direct competition to those of proprietary parts customers’.

Later proprietary engines would be sold to customers around the world, again under the Sturmey Archer label while complete machines remained under the Raleigh name. A similar situation existed with the cycle enterprises.

As WWI reached its final stages rumours developed – possibly fuelled by Raleigh – that the Nottingham maker was preparing for an assault on the motorcycle market once the war ended. It’s often difficult to discern the truth from rumours but facts tells us Raleigh and its chief designer-cum-works manager, William Comery, had taken out patents to protect the designs of a fore-and-aft flat-twin engine during WWI.

Raleigh came publicly clean in May 1918, announcing its planned post-WWI motorcycle, a 654cc short stroke (77 x 70mm – the short-stroke design helped pare engine length to a minimum) side-valve flat-twin. Unusually the gearbox was fixed to the frame, the engine and rear wheel moved back and forth to effect primary and secondary drive tension adjustment.

Raleigh came publicly clean in May 1918, announcing its planned post-WWI motorcycle, a 654cc short stroke (77 x 70mm – the short-stroke design helped pare engine length to a minimum) side-valve flat-twin. Unusually the gearbox was fixed to the frame, the engine and rear wheel moved back and forth to effect primary and secondary drive tension adjustment.

Other advanced features included leaf spring-controlled rear swinging arm suspension and a knock-out rear wheel spindle.

The flat-twin Raleigh was an advanced, sophisticated motorcycle for the discerning rider, but it was expensive and never destined to sell in the volumes the Nottingham factory’s board craved. Keen for increased sales, Raleigh announced in September 1921 an all-new single. With 71 x 88mm bore and stroke, the distinctive outside flywheel side-valve engine was coupled to a Sturmey Archer two-speed gearbox with belt final drive.

Sporting Brampton Biflex front forks made under licence by Raleigh, clean bars, aluminium footboards and neat lines, the new 23⁄4 hp model was well-made and at a competitive price. True, it was no racer but it came well within the 200lb taxation class and a sports model with semi-TT bars and footrests was planned. For the Olympia show Raleigh announced a 399cc (76 x 88mm – 3hp) model achieved by enlarging the bore for use with a light sidecar.

Sales in relative terms began to take off leading the Nottingham team to progressively unveil a range of singles with capacities of 248, 298 (299), 348, 399 and 496cc while V-twins were offered as 598 and 798cc. The history books tell us the 298 and 399cc models were simply half a V-twin, although if history is being strictly observed the larger V-twin is better regarded as two singles! A single 350cc Raleigh was entered by Victor Horsman of Liverpool in the 1922 Junior IoM TT. A Milner started the race to complete less than a lap. However, it wasn’t racing but trials and successful publicity stunts that were to be Raleigh’s forte during much of the Twenties. The tough Nottingham machines proved ideal and at one time Raleigh boasted Hugh Gibson and Marjorie Cottle as star turns.

In 1924, Hugh Gibson set off under ACU observation from Liverpool to ride round the UK mainland coast on a Raleigh outfit, while unobserved Marjorie Cottle headed off in the other direction. The pair covered 300 miles per day for 12 days, after six days in the saddle their routes crossed near Hull, and after another six days their epic finally ended 3429 miles later at Liverpool.

As money tightened during the Twenties Raleigh added an economy 174cc (52 x 58mm) lightweight to the range. Of claimed unit-construction the side-valve lightweight has pinions of different sizes on either side of the crankshaft, which mesh with larger gear wheels on a countershaft; a sliding dog locked one or the other in drive. In common with New Imperials and Honda step-thrus the engine runs backwards.

During another publicity stunt in 1926 Marjorie Cottle, covered 1370 miles in England and Scotland in 19 days at 120mpg on the lightweight, demonstrating the practical economies of motorcycling.

Keeping with the times, Raleigh introduced ohv designs in the mid-Twenties, first as a 350cc model and then the all-new 500 single. Towards the later Twenties, Raleigh rekindled its interest in speed. For a time, legendary Brooklands racer and tuner Daniel R (Wizard) O’Donovan joined Raleigh and they enjoyed some fine moments, including 1929 wins at Brooklands for CJ (Jack) Williams on a 495cc (79 x 101mm) model and privateer ‘Sid’ Brewin on a 350.

Keeping with the times, Raleigh introduced ohv designs in the mid-Twenties, first as a 350cc model and then the all-new 500 single. Towards the later Twenties, Raleigh rekindled its interest in speed. For a time, legendary Brooklands racer and tuner Daniel R (Wizard) O’Donovan joined Raleigh and they enjoyed some fine moments, including 1929 wins at Brooklands for CJ (Jack) Williams on a 495cc (79 x 101mm) model and privateer ‘Sid’ Brewin on a 350.

Raleigh’s return to the Island was rewarded with a best finish of fifth in the 1930 Junior for Jack Williams. In the same year, Raleigh won the Austrian and Argentine GPs and was placed third in Belgium. Despite these successes, Raleigh sales – in common with many – were on the slide because of the Great Depression. Efforts with new cradle frames and four-speed foot change gearboxes failed to save the day and the board axed motorcycle manufacture in 1933, although the 742cc Raleigh three-wheeler (Safety Seven) continued until 1937.

When Raleigh re-entered the power two-wheeler fold, the automatic RM8 was among the models offered. Motorcycle-wise Raleigh was down, but not out. In 1958 the firm announced a return to powered two-wheel manufacture with a 49.9cc Sturmey Archer engined moped coded the RM1. Although the engine was labelled Sturmey Archer, BSA built it for Raleigh and although the moped was OK, it wasn’t brilliant, leading Raleigh to tie up with renowned French maker Motobecane. In effect, Mobylette mopeds were assembled under licence in the UK by Raleigh and sold tens of thousands. Models included the RM4 Automatic, RM5 Supermatic, RM6 Runabout, RM8 Automatic 11, RM9 Ultramatic and RM12 Super 50. All were in effect twist-and-go mopeds, with similar if not identical Mobylette counterparts.

One model, which although built with much Mobylette help, had no French role model was the small-wheeled Wisp built 1967-68. Although often forgotten, Raleigh tried scooters, too. During 1960-64 it marketed the Italian-designed 78cc two-stroke Bianchi Orsetto scooter in the UK as the Raleigh Roma. A seemingly bizarre model name choice as the Bianchi factory was in Milan!

Raleighs are among the most underrated of vintage motorcycles. They are well built, honest machines which deliver reliable service decade after decade when well rebuilt for the vintage club rider.

Thanks to lacking the perceived charisma of Nortons, Velocette et al and thanks to surviving in large numbers, vintage Raleighs are available at relatively moderate costs. But you’d better be quick as their worth is becoming appreciated. The same is true of the honest, durable Mobylette mopeds assembled and marketed under the Raleigh logo.

Rambler c1948-61 UK

Brand title along with Roamer and others given by Norman Motorcycles of Ashford, Kent for export models to selected markets, especially Australia and some African countries. Note: An American concern built single and V-twin motorcycles under the Rambler marque c1903-1914.

RAP c1955-75 Holland

Pleasant, typically Dutch mopeds built with bought-in proprietary engines, including German Rex and later Austrian Puch 49cc two-stroke units. Few have found their way to the UK but they are often on offer at leading North European autojumbles, like Utrecht.

RAS 1932-36 (58) Italy

Another example of badge engineering, but why in this case, is lost on me. Italian FN importer, Achille Fusi of Milan, began making his own motorcycles in 1932 sold almost exclusively under the RAS label until 1936, after which the Fusi trademark was employed.

Ratier 1955 (1945)-62 France

Aircraft components maker from Montrouge, Seine who built 746cc ohc engined cars between 1926-30. After WWII the company began trading as CMR, then Cemec, although from 1955 its motorcycles were marketed as Ratier. The company assembled BMW-like motorcycles, especially a 746cc side-valve flat-twin with parts made in France for the German military during the occupation and left over after the war had ended.

Motorcycle production was then suspended until 1955 when it built a range of ohv and side-valve horizontally opposed transverse flat-twins to its own design. Although observers branded them BMW copies, there were many differing features and to make a point great play was made of the fact that the vast majority of components were ‘made in France’. Ratier ohv models were raced in production classes but the majority were kitted with radio, siren and pannier bags for police work.

Although 500 and 600cc ohv and 750cc side-valve models were listed, it’s doubtful that many 750s were built and before production ended of these well-made but expensive motorcycles the range was slimmed to variants of the 600 (594cc) model only.

An export drive to America was tried and President de Gaulle favoured the Ratier for escort duties on state and important government occasions. The BMW-like machines spotted in many of the old newsreels of Charles de Gaulle were in fact Ratiers – not BMWs – and they continued in use for this role some years after production ended in 1962. Survivors are sought after and seldom offered on the open market.