Silk 1975 (1971)-c1980 UK

That most useless of skills, hindsight, tells us the 1970s wasn’t the time to commence motorcycle manufacture, the UK wasn’t the place and a large capacity twin cylinder deflector piston two-stroke would only appeal to a very niche market. Despite all this, the Silk handled and stopped well and was exceptionally light, which enhanced its performance. Today, Silk can boast an exceptional survival rate.

On leaving school in the late 1950s, George Silk developed, through his first job, a passion for two-strokes. This passion soon focused on Scotts. Later, a partnership with Maurice Patey developed and the Silk engineering business found time to repair and performance-develop Scotts. In 1971, George fitted a 500cc Scott engine in a Spondon Engineering frame for the year’s Manx GP. This led to the development and building of a small run of Scott engined machines for customers.

After trying unsuccessfully to negotiate rights with Matt Holder to build the Scott engine at his Derby based engineering concern, George – with David Minglow – designed a 653cc twin cylinder two-stroke unit. With their design of a deflector piston it had the team’s patented ‘velocity contoured’ combustion chamber charge system – in effect a system that George felt combined the best of the deflector piston engine and DKW’s (Dr Schnuerle) loop scavenge system. Design complete, the Derby concern sought help with optimum porting from Dr Gordon Blair of Queens University, Belfast.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

The result was a flexible water-cooled two-stroke twin which produced 45bhp at 6000rpm – enough for a claimed 115mph, yet it returned what today we’d consider an environmentally friendly 60mpg. In a production run from c1975 to 1980, Silk built 138 rolling chassis and 140 engine/gearbox units. In addition, there were one or two special projects including a 500cc racer and a trials engine. The majority of engines were prepared for the sports tourer road model, the machine designated as the 700S. There was also a race prepared engine coded the SPR. The first 30 models were Mark I, with an all polished engine, then came the Mark II with a partially black engine. The 100th Silk was built in November 1978 and the last production model in February 1980. During this time Silk continued with engineering work and built industrial engines.

Silver Pigeon (Pidgeon) and Pigeon 1948-65 Japan

Better known today for their Shogun four-wheel-drive vehicles, the Japanese military aircraft (Zero-San) maker Mitsubishi introduced their first scooter the 115cc two-stroke C-11 Pigeon, in 1948, only two years after Fuji had built Japan’s first scooter. Mitsubishi’s first 30mph scooter, looked, with its tiny five-inch wheels, like the Motor Glide.

Continuing with their basic styling, Mitsubishi introduced the uprated C-13 in 1949, with larger headlamp. As the Pigeons flew into the 1950s they hatched an ever increasing range, including in 1950 the 150cc C-21 with the options of either tradesman or passenger sidecars. The restyled 150cc C-22 appeared a year later, still looking fairly rugged but with air ducts occupying every surface of the scooter’s rear. The first four-stroke with its 175cc unit coupled to a three-speed gearbox and eight-inch wheels came in 1953. It still retained the Pigeon’s initial agricultural styling.

For 1954 the Pigeon gained style and sophistication with the all new C-57. Powered by a 198cc four-stroke engine with automatic transmission, it was an early – and highly successful – twist and go scooter. Its bodywork was both curvaceous and slab sided, set off with lots of chrome, endless cooling ducts and full indicators.

Two years later the model was updated, with even more chrome, as the C-57 11. Using the same engine and transmission, the model was re-styled with sleeker bodywork as the C90.

While all this was going on, in the 200cc class Pigeon continued with their smaller models which were restyled in 1955, Mitsubishi having had a long hard look at the Lambretta LC model first to give the C-70. This was followed by the similar but updated C-73 in 1958 and a 192cc four-stroke version coded the C-74 a year later. To complement this and the two-stroke C-73, a four-stroke 125cc model, the C-83, appeared, which looked uncannily similar to the Lambretta TV175.

Into the 1960s, and the models were again updated alongside the new 125cc C-90, the 200cc C-200. As well as these was the top of the range 210cc Peter De Luxe. Also, two higher performance ohv models appeared, the 175cc C-110 and larger 60mph 210cc model C-111, sculpted with a mix of heavy German type dustbin front and sleeker Italian rear. Further styling led to the 125cc C-135 of 1963 plus the C-140 and C-240 of 1964.

Depending on the market – as many Mitsubishi scooters were destined for export – they were sold variously by their code numbers and the Mitsubishi brand, or the link with Mitsubishi was deliberately omitted, in which case they were often branded as the Silver Pigeon (or Pidgeon depending on source of promotional material). Other times the brand Pigeon (Pidgeon) was used, which was or was not linked to Mitsubishi.

One of the largest export markets for Mitsubishi scooters was the USA, where from the middle/late 1950s until the end of production they were imported by the Rockford Scooter Company of Illinois as the Silver Pigeon. Rockford was particularly careful to omit any reference to Mitsubishi. As one of the Japanese builders of the Zero-San military aircraft, which had been heavily involved in the bombing of Pearl Harbour, the name Mitsubishi would have attracted plenty of ill feeling…

From the outset, Rockford often implied they were the manufacturer of these scooters and even employed briefly other brand names too in an effort to cover their trail. Later, they sold large numbers of the different model Silver Pidgeon scooters to the American mail order giant Montgomery Ward, who usually marketed them as the Riverside.

Fuji and Mitsubishi can be regarded as the Japanese equivalent of the Italians Innocenti and Piaggio. Volume wise their production levels were impressive, in the early 1950s Japanese makers were building in excess of 50,000 scooters per year, with Fuji and Mitsubishi accounting for the lion’s share, and by the late 1950s their total annual output was approaching 100,000 scooters per year.

SIM 1951-55 Italy

Hoping to compete with Piaggio’s Vespas and Innocenti’s Lambrettas, SIM (Societa Italiana Motorscooters) of Reggio Emelia worked with motorcycle/car maker Giovanni Moretti and the Austrain Puch factory to make top scooters. The Gran Lusso, powered by a 125cc split single Puch two-stroke engine, was first off the assembly line followed a year later by the naked Ram or Ariete with SIM’s own 150cc two-stroke engine and shaft drive. In 1953 the Ariete Sport was unveiled, in effect an Ariete with Gran Lusso style scooter bodywork. SIM scooters were well made machines offering good handling.

Despite strong marketing campaigns using the best of advertising copywriter’s prose they couldn’t dent Piaggio’s and Innocenti’s stranglehold on the Italian market leading to an end of production.

Simard 1952-54 France

Sidecar maker from Villeurbanne (Rhone) who branched out into scooters with some success for a brief period. Looking similar at first glance to a Lambretta LC, they were powered by Ydral proprietary engines, usually 174cc units.

Simoncelli 1927-35 Italy

Small manufacturer of proprietary engined models, which began with two-stroke lightweights and then added JAP side-valve and ohv models to range. Unsure of any survivors, but Simoncelli deserves a mention as they developed an advanced rear suspension system in the early 1930s that went into production c1934, which was later imitated (with modifications) by other makers.

Simonini 1973-83 Italy

Enzo Simonini began building superb lightweight motocross machines in a small workshop at Maranello near Modena, little more than a stone’s throw from the Ferrari works. Demand outstripped the capabilities of the Maranello workshop, forcing Enzo to move to larger premises at nearby Torre Maina. Initially relying on Sachs power – which he successfully further tuned – Enzo was encouraged to market tuning kits for Sachs and other lightweight two-stroke engines.

Demand again outstripped the Torre Maina work’s capabilities, forcing Simonini into partnership with Fornetti Impianti SpA of Maranello.

With more finance, a new production factory was taken over in 1975 and the Torre Maina plant retained for research and development. A new range of on and off-road models were built using Kreidler 50, Minarelli and up-to-250cc Sachs units. They also developed their own superb 125cc unit named the Mustang for motocross use.

Road models included well crafted sports motorcycles, complete with full fairing, twin disc front brakes and highly tuned engines. Towards the late-1970s the business was further expanded with new liquid-cooled lightweight models, often with Sachs power. Despite all this apparent success, Simonini experienced a sudden drop in sales, financially struggled and production of machines and tuning kits ended in 1983.

During the mid-1970s Simonini enjoyed some national competition success, with motocrosser Giuseppe Fazioli winning the 125cc Junior title in 1975 as a high point. Many clubmen rode them to success and the marque briefly appeared in the International motocross world in the mid-1970s, was represented in some British 125cc events and competed in the ISDT.

Simplex 1902-1968 Holland

The Dutch concern was one of at least four marques worldwide to use the Simplex brand. The Amsterdam maker was for decades Holland’s largest-by-volume motorcycle factory. Based in Utrecht, the Simplex Weighing Machine Company, motivated by the cycling boom, established a cycle making division employing initially around a dozen workers. Over the next five years the workforce and output continually grew, forcing Simplex to seek new premises for their thriving cycle business.

In 1894/5 the business moved to Amsterdam and in the autumn of 1896 was restructured to become NV Pijwielfabriek Simplex, which near translates to the Simplex Bicycle Factory Ltd. In 1898, Simplex built their first prototype car and a year later another company, NV Machine Rijwiel-en Automobielfabriek Simplex, was formed. However, later motorcycle literature usually carried the simple legend Rijwielfabriek Simplex.

They then also began experimenting c1901 with motorcycles, using Belgian-made Minerva kits, with Minerva’s automatic inlet valve engine clipped to the downtube of Simplex cycles. In 1902, Simplex’s first pre-production prototype was unveiled and within a year they switched to full mechanical valve operation Minerva engines, fitted upright within the main frame.

By 1902, Simplex was fitting German Fafnir engines to their voiturette, then to their motorcycles. Come 1905, a three-wheeled light commercial truck had joined the range along with a three-wheeled car and a forecar attachment for their motorcycles. Both water-cooled and air-cooled engines were available for the three-wheelers.

Recession over, Simplex unveiled new models for the 1911 season, including 2 and 41⁄4hp singles and a 5-6hp V-twin. Later a 21⁄2hp military model appeared and by 1913 they’d begun using Swiss MAG engines. Production of cars and motorcycles was suspended from 1915 for the duration of WWI.

Although car production never restarted, the Amsterdam company picked up their motorcycling interests, returned to trials competition in 1921 and soon were offering an extensive range of models from 21⁄2hp (300cc) lightweights to huge 9hp V-twins. They also offered a range of sidecars. With updates, this policy continued until the mid-1920s.

Circa 1925, Simplex adopted Blackburne engines, especially 350cc ohv and side-valve singles, and they briefly flirted with 350cc ohv oil-cooled Bradshaw power too. Within a year they had dropped all other proprietary engines to focus on a Blackburne-engined only range. By 1930, Simplex were moving away from larger motorcycles and launched a 72cc Sachs-engined autocycle type machine. A couple of years later they experimented with electric-powered cycles. Then came a smaller range of Villiers-engined machines from 98cc Midget powered models to 250s with either air or water-cooled units. In the late 1930s a Villiers 125cc-powered machine was launched and in 1938 a 60cc Simplex Saxonette, which remained in production until WWII.

After WWII, Simplex concentrated on cycles until combining their business with Dutch moped makers Locomotief, which led to mopeds with the famed Simplex logo. Briefly, sales were satisfactory, then slipped. To salvage the business, Simplex merged with the Dutch maker Junker. In 1968, they were taken over by Gazelle and the Simplex name was never to appear on motorcycles or mopeds again.

Simplex 1921-50 Italy

Founded by Luigi Pellini (ex Pellini and Ferrari) Simplex production began modestly with 124cc clip-on engines, then came a neat unit construction 149cc ohv motorcycle. Pellini actively developed and refined his motorcycles, adding an ohv 174cc unit construction lightweight, then larger up-to-500cc machines. After WWII the factory staged a brief comeback with up-to-250cc models to pre-WWII designs.

Simplex 1919-22 UK

One of a number of tiny cycle attachments which briefly appeared after WWI, the Simplex was powered by a 105cc deflector piston two-stroke engine.

Simplex c1935 mid-1970s USA

Tiny, rigid mini motorcycles, most powered by pull-start Clinton four-stroke industrial engines. They were intended for stowing in a car boot, boat or caravan, ready for short distance errands. Some had a pillion perch and all used small industrial wheels with pneumatic tyres.

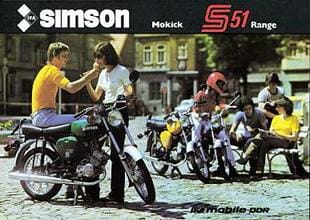

Simson 1952 (1938)-c2000 Germany

Like BSA and FN, Simson’s past lies in armaments. Founded in the German Thuringia town of Suhl as the Ernst Thalmann Hunting Weapons Works, they made their first cycles in 1896 – these were advanced upmarket bicycles with pneumatic tyres for the discerning rider. With financial backing from their successful armaments company, car development began in 1900.

Surprisingly, they didn’t market their first models until 1911 and were trading as Simson & Co with their cars branded the Simson-Supra. Early models either side of WWI used conventional 1559cc and 2595cc ioe four-cylinder units. In 1924, Paul Henze joined Simson and soon developed sohc and dohc 1960cc four-cylinder car engines, the dohc unit with tuning producing up to 66bhp@4000rpm, then came a 3108cc ohv straight six car and finally a 4673cc side-valve straight eight. Throughout, the majority of models were either quality tourers or sportscars.

During the late 1930s, Simson looked seriously at manufacturing economy light motorcycles, beginning with a 98cc two-stroke single cylinder Sachs-engined model in 1938. WWII scuppered their plans. After postwar partitioning of Germany, Simson found themselves in the Eastern zone. In 1952, they launched a 49cc moped (SR-1) which was later superseded by the SR-2, which was for more than a decade East Germany’s best selling motorised two-wheeler.

Hot on the heels of the SR-1 moped came the AWO 425 (325), a shaft-drive 250cc single cylinder ohv motorcycle, similar to the period BMW, EMW, Universal etc. Developing 12bhp, the tourer made 100kph (62mph). A racing version with a huge fairing captured the 250cc East German Road Race Championships 1953-55 and trials variants performed well in two and six day off-road events.

Facelifted in 1955 with full swinging arm spring frame to make a handsome motorcycle; it was joined by a mildly tuned sports version. Alongside this development came Simson’s first scooter, its two-stroke engine based on the moped unit. In 1958 Simson unveiled the RS250, a dohc 250 single cylinder road racer with six-speed gearbox, chain drive and leading link front fork. Resplendent with polished aluminium tank and fairing, it took Hans Weinert to successive East German National road race titles in 1958/9.

For the 1960s, the older models were again tweaked, while Simson considered an all ultra lightweight programme. The shaft drive 250cc four-stroke was reworked one last time, with the model flagship the Simson Sport 250.

A new scooter, the KR50 (Klein Roller = Little Scooter), with 16in wheels and newly designed 47.6cc two-stroke engine was unveiled. Certainly not the greatest scooter in the world but sales were strong in East Germany, as Simson was state owned along with all rival makers, which eliminated any direct opposition!

Other development revolved around up to 100cc lightweight motorcycles in roadster, off-road and trials trim. By the mid-1960s, Simson’s enthusiasm for the off-road scene was apparent in their superb 50 and 75cc ISDT models, which for years were strong contenders in the small capacity classes in national and international long distance trials. Simson progressively adopted spine frames.

The range was continually updated. The scooters gained more power (3.4bhp), Earles type front fork, streamlined bodywork and the name Schwalbe. Selected motorcycles gained names too including Spatz, Sperber and Star. Others retained codes and some gained a massive leap in power including the hot GS75/1, which developed 9bhp at 8200rpm. Not bad for a 75cc two-stroke single.

In the 1970s, Simson consolidated more than developed. However, there were detail improvements and the scooter – which had been dropped in the late 1960s – was reintroduced as the updated Schwalbe KR51-1, KR51-1S and KR51-1K. In 1974 a new model, the S50B, was launched.

A cross between a commuter and sports motorcycle, it continued in production for years, with larger 70cc versions too. These models were exported worldwide and were the first Simson many countries had seen, despite the factory being a large volume maker.

After the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, Simson found trade harder and, without subsidies, export markets were less keen on their products, as they naturally became dearer. In a fightback, Simson restyled and improved specifications with models such as the Sperber 50 with disc front brake and Aprilia-like styling.

Singer 1900-15 UK

Coventry court records tell us Edwin Perks was hauled into the dock to answer the serious charge of theft in November 1898. Perks, a fitter with the Beeston Motor Company, was accused of stealing £10 worth of engine parts and raw materials from his employer. In defence, Edwin stated his MD sanctioned his actions – claims the MD, Mr S Gorton, denied. A year later Perks took out a patent for his motor wheel, suggesting the outcome went in Edwin’s favour.

In 1899, Perks rented a small workshop at Eagle Street, Coventry, and was joined in partnership by Harold Birch. Production of the neat Perks and Birch Motor Wheel began. The unit comprised a 198cc engine, fuel tank, surface carburettor and low-tension magneto mounted within the compass of a double-sided cast aluminium spoked wheel. Drive was by a toothed pinion from the engine to an internally toothed ring mounted to the wheel.

A year later Perks and Birch sold their patents, stock and manufacturing rights to the Singer Cycle Company of nearby Canterbury Street. Founded by George Singer, who’d earlier been a innovator within the fledgling cycle industry, Singer had used many of the first 200 P&B units to power their cycles and tricycles.

George Singer improved the design both mechanically and technically. One of his inspired improvements was to employ a single-sided cast aluminium spoked wheel, improving access to the engine for maintenance. Marketed as the Singer, most were of 198cc, although a larger version was built. It replaced either the front or rear wheel of a cycle. Singer also built complete motorcycles by installing the motor wheel in Singer cycles.

Powered tandems and tricycles joined the range. Then, rather cruelly, the wheel was installed in Tri-Voiturettes designed to carry more than one passenger and, even worse, Singer Governess Cars, built for those who wanted to ‘go motorcycling en famille!’ Many took their first hesitant rides on Singer motorcycles or tricycles, including the renowned trials rider Muriel Hind and, as an undergraduate, Ixion was captivated by one.

By 1903/4, motorcyclists and motorists wanted something better than a motor wheel powered device, but the motor wheel had served well, proving to many that motorised vehicles were viable.

During 1904 Singer introduced a side-valve lightweight, its engine conventionally placed, and after a couple more years they dropped out of motorcycle manufacture to concentrate on their blossoming car business, which began in 1905 with a 15hp three-cylinder model built under licence from Lea Francis. Within a couple of years, this was replaced by a range of cars built with White and Poppe engines of different capacities. Cars were on their way.

In 1909, Singer returned to motorcycles with a Moto-Velo, built along Motosacoche lines, soon followed by a conventional 299cc motorcycle and then a 499cc single. They were top quality roadsters, which with tuning took George E Stanley to many hillclimb and Brooklands victories and records. An ex-Premier man, Stanley – like Daniel O’Donovan – was known by the nickname ‘Wizard,’ a tribute to his tuning skills.

Keen for further racing honours, Singer contracted Louis Coatalen to develop an ohv racing model with a four-valve cylinder head. Unusually, the cylinder head was water-cooled, the barrel air-cooled, while the inlet valves faced forwards and the exhaust backwards.

The machine was planned for the 1911 IoM Senior TT but was never raced although Arthur Dixon tested it at Brooklands in 1912. While tuned Singers were hot Brooklands mounts, their IoM best was a fifth in the 1913 for another Brooklands regular, Jimmy Cocker.

In 1911, Singer launched a unit construction two-speed 535cc side-valve single aimed at sidecarists. Later in the same year came a 299cc unit construction single. This was bored out to 350cc for the 1912 IoM Junior TT, in which Wizard O’Donovan dropped out and Harold Petty finished seventh. For the 1913 season, the biggest single was bored out to 560cc, while the 299cc model was offered with the option of a dropped frame for lady riders.

Stanley left Singer for Triumph, his racing mount being passed (sold?) to Victor Horsman, who sometimes entered under the pseudonym EH Victor. Again the Singer – along with those of Jimmy Cocker, Arthur Dixon and others – went indecently well.

Singer’s last model, a 350cc two-stroke, was launched as the world was readying for war. With a growing car business, the Coventry maker didn’t return to motorcycle manufacture, although they were to play one more hand. In the early 1920s they bought rival Coventry maker Premier, who’d also stopped motorcycle manufacture in 1915 – however, this purchase was for the premises, not the motorcycles.