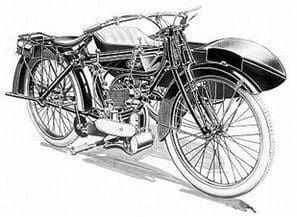

Sirrah c1921-25 UK

Manufactured by Alfred Wiseman and Son of Glover Street, Birmingham, who also built Weaver ultra lightweight machines and the dearer but better equipped Verus models. It’s stated in many sources the name Sirrah is derived by reversing the name of the designer Mr Harris.

Sirrah – like Verus – offered a relatively large range of machines for a small maker, ranging from 250/269cc two-strokes to 1000cc V-twin engined side-valve four-strokes. First announced in autumn 1921, Sirrah was to offer a range of models employing many engines, including Wiseman’s own two-stroke of approximately 250cc, Villiers 269cc units, side-valve and ohv Blackburne single cylinder units and JAP engines of up to 1000cc.

Among the many machines offered were TT models – although no Sirrahs ever raced in the IoM – but the firm did enjoy some local success at hill climbs, sprint events and trials.

SIS 1950-unknown Portugal

Established cycle maker who took on Portuguese import and distribution agency for German built Sachs proprietary motorcycle and stationary engines. Used Sachs 49cc two-stroke units for SIS mopeds and up to 98cc engines for lightweight motorcycles and autocycle type machines.

Sitta 1950-55 Germany

Production began with up to 247cc Ilo two-stroke engined motorcycles, then up to 125cc Ilo engined scooters and finally 49cc Ilo powered mopeds. Built in relatively small numbers compared with some German rivals, though odd survivors surface at European autojumbles.

SJK c1956-c1963 Japan

Another rare and sought after find for the collector of Japanese motorcycles. Built up to 249cc motorcycles and 49cc mopeds but never exported to Europe.

Skootamota 1919-22 UK

Granville Bradshaw designed, Gilbert Campling-built 123cc four stroke scooter. Best of a rash of primitive scooters built in response to an expected public demand for cheap personal transport after WWI. The Granville Bradshaw designed Skootamota comprises child’s scooter-like tubular steel welded frame, engine over the rear wheel, no gears or suspension, simple controls and a pedestal seat.

Slavia 1899-1908 Austro-Hungarian Empire (Czechoslovakia)

Range of single cylinder and later also V-twin engined machines built in the Laurin and Klement factory. Brand name briefly used by German S&N factory (Erika typewriter makers) for Laurin and Klement models assembled under licence. S&N also sold these machines under their own brand and – again briefly – Germania.

SMW 1923-33 Germany

Production began with small four-stroke fore-and-aft flat twins using Bosch Douglas engines built under licence, then added larger flat twins using 493cc BMW units. In 1928, Karl Ruhmer revised the range to include lightweight Villiers engined models and larger motorcycles with either Blackburne or Sturmey-Archer power.

S&N 1901-08 Germany

German S&N typewriter company built Lauren & Klement machines under licence from Austro-Hungarian maker. Their products were sold as either S&N or Lauren & Klement.

Socovel 1947-55 Belgium

Production began with 125cc lightweights followed by fully enclosed 122cc and 197cc Villiers engined models with pressed steel frames. Ilo and Sachs two-stroke powered models were added to the range and for a time 246/346cc single cylinder two-stroke Jawa engined models. As complete machines these looked like the Czech built Jawas, suggesting they were built or assembled from kits supplied by Jawa.

Sokol 1936-WWII Poland

BSA Sloper 600cc side-valve like machine with Sokol’s own engine made for the Polish military.

Solex 1949-(1980)-1991 France

See Velosolex

Solo 1949-82 Germany

Built almost exclusively for the home German market, production began with 49cc moped-like machines which were refined through the 1950s. Manufacture continued to focus on under 50cc mofas, mopeds and ultra lightweight motorcycles until the mid-1970s when small ‘city bikes’ were introduced. Solo also developed and marketed an electric moped. A modest number survive which were initially surfacing in Germany only; however, they are getting dispersed through Europe as they are sold on.

SOS 1927-40 UK

Founder Len Vale-Onslow was one of motorcycling’s characters – a larger-than-life rider/businessman who set out to build a better motorcycle than those of rivals using like power sources, with JAP singles for some early models and Villiers power throughout the production run. Vale-Onslow was not only an engineer who knew what he wanted to achieve but also his own best publicity agent.

All of us understand the maritime distress signal SOS (save our souls). Len used these letters for his marque… who was going to forget SOS? Initially SOS was an acronym for Super Onslow Special; then as sales and sporting success followed, SOS equalled Success On Success.

Then, in the mid 1930s, the slogan was changed again, SOS standing for So Obviously Superior. An almost Brough-like piece of publicity which isn’t that surprising as Leonard Vale-Onslow and George Brough knew each other, competed as rivals at sporting events and both considered themselves the only ‘designer/manufacturer/sporting motorcycle riders’ in the world. Hardly a modest claim – and one without much substance as many Italians and others could point out.

The promotion didn’t end with hype alone as the product was pretty good. Mr Leonard Vale-Onslow – or ‘Mister’ as he was known by many – offered a superb standard of fitments and finish on his machines: tubular girder forks instead of the pressed steel fitments of economy-minded rivals keen to pare every penny off the price; sporting lines; frames built in chrome-molydbenum aircraft tubing (oxy-acetylene welded and patented); pie crust tanks and a superior level of finish. Although SOS motorcycles could be specified in a variety of tank finishes, ‘Mister’ favoured a two-tone tank job in Oxford and Cambridge University blue, the colours of Len’s school, Lyndhurst College, Erdington.

During autumn 1927 The Motor Cycle carried announcements of the first SOS motorcycles. Designed and built by Len in a small workshop at Hallow, Worcestershire, he set out to build machines which were economical and comfortable couple d with speed and reliability (Vale-Onslow’s words.)

d with speed and reliability (Vale-Onslow’s words.)

From the outset, other than frames, SOS employed predominantly proprietary parts; usually Villiers – although some early models were offered with JAP power – often Albion gearboxes, Webb front forks (although the first few models used Druids) and fuel tanks made by Tallboys of Witton who made the pie crust tanks for Norton.

SOS offered 172cc upwards Villiers power and JAP single engines to the 1930 season, but from 1931 on they continued with 172cc to 346cc Villiers power and for a time their own 148cc and 172cc water cooled two-stroke engines. In addition water cooling was available on certain Villiers powered models at extra cost. Trials and racing versions were offered, most notably using the 172cc Villiers Super Sports and Brooklands engines, although others were also employed to customer’s demand for specific machines. For a brief period SOS included a dedicated grass track model in their range.

After four years at premises in Hallow, SOS production was moved into Birmingham. In October 1933 Surrey-based Brooklands racer and Villiers specialist Tommy Meeten took over running SOS. Choosing to maintain the Birmingham assembly line rather than move the operation south, SOS production continued until WWII. At its peak it’s claimed 15 motorcycles were built per week. After WWII, Meeten continued with his profitable Villiers agency and Len Vale-Onlsow his Birmingham motorcycle dealership.

In addition to trials, sprint and grass track success, SOS Motors Ltd enjoyed a single IoM Lightweight TT finish in 1929, as H Lester finished 10th at 58.70mph, 22 minutes behind Syd Crabtree’s winning Excelsior.

Southey 1905-c1925 UK

Although a small volume producer with no known survivors, Southey was better known in period as proprietary frame makers.

Soyer 1919-37 France

Paris marque which traded from 204 boulevard Periere with manufacture taking place at 116 rue de Paris, Colombes and later at Levallois. Production began with 250cc models with either full motorcycle frames or dropped framed ladies’ models. Soon the range was expanded to include from 98cc two-stroke utility models to lusty 500cc four-stroke singles. With forward thinking, Soyer added ohv and later ohc models to their range.

Although they manufactured many of their own two-stroke engines, they didn’t make a volume production in-house four-stroke unit, instead favouring engines from JAP, Sturmey-Archer, Chaise or Aubier et Dunne.

Backing motorcycle sport including trials and road racing, Soyer enjoyed the satisfaction of winning the 1930 French GP.

Spake 1911-14 USA

Maker of ioe single and V-twin motorcycles which also supplied proprietary engines.

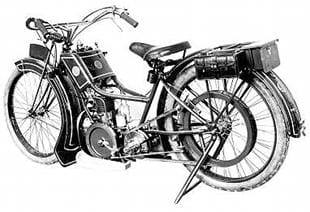

Sparkbrook 1912-25 UK (Spark 1921-23 UK)

Founded in 1883, the Sparkbrook Manufacturing Company Ltd of Coventry began making motorcycles for the 1912 season – initially large V-twins, then larger capacity singles. By 1914 lightweight models powered by either Villiers 269cc two-stroke single cylinder engines or the slightly larger inlet over exhaust valve 349cc Villiers four-stroke unit were being made.

After WWI production restarted with a range predominately based around the Villiers 269cc two-stroke engine. By 1921, the range had grown to include side-valve JAP engined singles – a range which continued with some updates including all chain drive (rather than chain-cum-belt) on the more expensive models until production ended. Spotting the motorcycle market could plummet, Sparkbrook introduced a cheaper 269/247cc Villiers two-stroke powered economy lightweight range, including a direct belt driver at just 38 guineas (£39-90), named the Spark. Additionally, Sparkbrook part built or completely built motorcycles for others to re-brand.

Sparta 1931-72 Holland

Well known Dutch cycle maker who began with two-stroke cycle attachments. Then came up to 100cc Sachs and Villiers engined autocycle and lightweight motorcycle machines followed by up to 200cc two-stroke models powered by Ilo, Sachs and Villiers units. After WWII came 122/197cc Villiers engined motorcycles and up to 250cc models including a 244cc Ilo twin engined model and mopeds.

It was for their mopeds Sparta became best known and after 1960 the Dutch factory concentrated on 49cc mopeds alone.

Sparton c1976-85 UK

Yamaha racer Barry Hart – with the help of others – began developing his own five and six-speed gearboxes for some Suzukis and Yamahas. Marketed as the Barton, these found favour with some racers. Hart next developed a 458cc two-stroke triple race engine based on a Suzuki 380 bottom end. Housed in a frame built by Spondon Engineering, this became the first Sparton. The association between Barry Hart and Spondon Engineering continued.

As ideas and work progressed, Barry Hart moved from London where he’d built the Barton gearboxes to Caernarfon and later to a disused chapel a few miles out of town. Next came the Phoenix four project. Of similar layout to the two-stroke square four Suzuki RG500, the new engine was all Barry’s work. Sharing identical bottom ends, the engine was offered as 54x54mm 500cc four or 66.4 x 54mm 750cc four.

The marque was given a super racing boost as the earlier triple clocked 146mph through the Highlander speed trap at the 1975 IoM TT races, followed by a first and second in the year’s North West 200 with Martin Sharpe and Frank Kennedy aboard.

As the Phoenix project gained momentum, Geoff Barry joined them in 1977 as development rider but was killed later in the year while leading at the Dundrod circuit on a 750cc Yamaha. Graham Wood continued the work as development rider.

Special-Monneret 1952-58 France

Some authorities report Georges Monneret maintained small volume production of sporting lightweights with two-stroke proprietary engines during the 1950s. No known survivors are known to the author but included as Georges Monneret was one of the world’s great motorcyclists who must have clocked far more high speed laps at the banked Montlhery track south of Paris than any other rider.

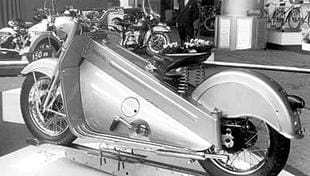

Speed et Mors-Speed 1949-56 France

Mors were a pioneer of the French car industry, which began automobile production in 1895, when Emile Mors installed an air-cooled flat twin and then V-four engines in basic chassis. By 1902 Mors had progressed to water-cooled chain driven cars and later built top quality cars of up to almost 13,000cc. For a time, the engineer Andre Citroen – founder of Citroen – was on the board of Mors.

Mors car production ended in 1925 but the firm continued making proprietary parts for the automobile and commercial vehicle industry. During WWII – and possibly just after – the company made electric cars and in 1949 began development of Pierre Brissonnet-designed 60-125cc two-stroke scooters at its Sens factory. Often using Motobecane engines, the futuristic 125cc scooter was claimed to be good for 75kph two-up.

Speedway c1944-48 USA

Nippy miniature scooter and motorcycle with identical 6bhp engine. Both were claimed to reach 60mph, which must have been an interesting experience.

Spiegler 1923-32 Germany

The Spiegler brothers first made flat twin lightweights and cycle attachments at their Aalen factory under the Schwalbe brand, then used their surname for the motorcycles that followed.

Most Spieglers used a pressed steel box section spine that enveloped the steering head, housed the petrol tank and terminated at the rear wheel axle. From this a tubular steel cradle (usually duplex) ran from the steering head, under the engine and again to near the rear wheel axle.

Spiegler often used JAP or MAG ohv or side-valve single cylinder engines of up to 600cc. As the world recession bit they introduced a 198cc JAP-engined lightweight in 1929.

Spiriditis c1952-c1985 Latvia

Two-stroke 123 and 246cc motorcycle built at the Sarkana-Swaigsne works, Riga. Later switched to 49cc two-stroke ultra lightweights and mopeds.

Spring 1910-24 (1940) Belgium

Modest producer of transverse V-twins, then added transverse V-fours, most with front and rear suspension. After WWI, La Sa des Ateliers Systeme Spring of Streupas-Angleur et Tilff-Liege revised their suspension system and predominantly focused on a range of 498-998cc transverse V-twins intended solely for sidecar work.

Displayed at the 1920 Brussels show, models with forward mounted engine in unit with gearbox and magneto sitting on the engine were put through a number of arduous tests for publicity purposes. Sales were never strong and manufacture ended c1924 – however, the firm continued as a mechanical engineering shop. Some past scribes claimed further odd machines were built until WWII, but there is little evidence to support this. Survivors are claimed to exist but none have been offered for sale in recent years.

Sprite 1964-71 UK

Brave attempt by second-hand motorcycle dealer and AMCA off-road competitor Frank Hipkin to build what he wanted to ride. Using a small old building next to his Handsworth, Birmingham motorcycle business – a business that specialised in second-hand scramblers and trials motorcycles – Hipkin began building one-off specials to suit his requirements. Although Frank felt these a vast improvement on what was commercially available, few enthusiasts outside the Birmingham area ever saw them as he usually rode in local Amateur Motor Cycle Association (AMCA) events, of which there were plenty enabling him to test his ideas.

By 1964 Hipkin’s concept of what made a perfect scrambler was honed and he was persuaded to build six more machines for fellow local clubmen. Basically, the machine comprised a strengthened and stiffened Cotton Cougar frame with Norton front fork housing Hipkin’s own built engine made up of Villiers crankcases, Alpha crankshaft assembly and Greeves barrel with revised porting.

Soon sold, Frank Hipkin was inundated with demands for more. Larger premises were found in the form of an old house in Cross Street, Smethwick and a sort of production line was set up making in kit form about half a dozen machines per week. Frames from what looked like water pipe were welded in the kitchen, steering head bearings were bedded in glass fibre and final assembly into the kits was completed in the Cross Street house bedrooms before being taken down a set of outside stairs ready for direct dispatch. With an instant high demand every inch of space was utilised – even under the outside stairs, where the frame tubes were stored!

As a competitor who understood all about frame design, steering head angle, ground clearance and optimum power characteristics for either trials irons or scramblers, Hipkin advanced competition design. Some of the production methods may have gained him derision from rivals but when Sprite sales suddenly soared they had little to smirk about.

Not only had Frank cut production costs, yet managed to build competitive machines for the clubman, he made full use of direct trading and a loophole in the purchase tax legislation. By selling in kit form – which involved the buyer doing little more than install engine, controls and drive chain plus fit wheels – no purchase tax was involved and, by selling direct to the customer so avoiding the established dealer networks, new Sprites were over £100 cheaper than comparable models from Greeves et al. Suddenly, many riders opted for a new Sprite instead of a second-hand Greeves, BSA C15 or whatever.

With trials models powered by either Villiers 32A or 37A engines selling well, Sprite then developed a frame with oil carried in its rectangular top tube to accept the 500cc Triumph twin engine. As his stock of Norton forks dwindled, Hipkin developed a leading link type fork controlled by Girling shock absorbers.

Clearly Hipkin had hit on a winning formula, which encouraged other rival makers to offer machines in kit form to avoid UK purchase tax. In less than a year Sprite outgrew the makeshift Cross Street premises and moved to a purpose built factory Hipkin had commissioned at Eel Street, Oldbury, Staffordshire. Next Sprite set up its own glass fibre workshop to make tanks, seat bases, mudguards and other bodywork and in just over two years from making the first batch of six machines Sprite secured the first export order of Villiers 34A and 36A scramblers for the American market.

Works support was instigated almost from the start of production with Ray and Ron Jordan riding in Midlands scrambles and – bravely – Hipkin signed youngster Dennis (Jonah) Jones as development rider; although a natural rider, Jonah certainly ploughed his own furrow. Other Sprite supported trials riders included Sam Cooper, Chris Leighfield and a young Mick Wilkinson. Sprite eagerly supported scrambling, especially televised scrambling with Brian Hutchinson (Maico Sprite) and Terry Challinor (Husqvarna Sprite).

Sprite began offering Robin Humphries-made telescopic front forks (REH) as an option, making the models lighter still, although the Hipkin leading link fork remained on offer. With Jonah scoring class or outright wins at Nationals as well as at the Manx, Sprite sales rocketed, and this despite the increasing popularity of Bultaco and the many victories by Sammy Miller.

Ever the businessman, Frank wasn’t opposed to earning extra income selling larger capacity tanks, REH Ceriani type forks and other items separately to either update older Sprites or even for rival makes. With the trials models starting at £133.50 for iron barrelled Villiers 37A engined trials kits and £164 for models with telescopic fork the cheap but well developed Sprite became the clubman’s choice, and made winners out of plenty. And although not considered a top quality engineer-built machine, the modest cost combined with many trials and scrambles victories helped build for Sprite an enviable export trade to the USA and Europe.

Sprite developed its own 360cc two-stroke scrambles engine – which wasn’t unlike the Husqvarna unit – and in September 1967 launched the Sprite MkII trials models. Prices started at £169, again in kit form, for the entry level Villiers 37A powered models. All now had revised nickel plate frame, lightened Motoloy hubs and weighed just 200lb. Jonah had left Sprite after a difference of opinion with his boss and was replaced by John Hemmingway. Next, a 405cc scrambler engine was developed. The completed machine sold on both sides of the Atlantic as the Goldfinger scrambler.

With Villiers engine production ended and the supply of 37A units drying up, Hipkin briefly tried to re-port the Starmaker engine, of which there were still good stocks, for trials work, with no more success than anyone else who tried. On the rebound, Sprite came up with a 125cc Sachs engined mini trials motorcycle, which was ridden in the 1968 British Experts Trial by Hemmingway, Rob Edwards, Roy Peplow, Jim Sandiford and Norman Eyre. Weighing 160lb, the 125cc Sprite trials model, sold as the Goldfinger Mini in the UK or the Apache in the USA, sold well initially as did rival mini trials machines.

![]() Sprite took over a small foundry and renamed it Sprite Alloy Castings, to cast cylinder heads, crankcase and other parts and moved premises once again, to Stourbridge Road, Halesowen. Contracts were won to supply many thousands of 405cc Sprites to USA importers American Eagle (McCormack International). Further models were exported to Australia and a few to Northern Europe.

Sprite took over a small foundry and renamed it Sprite Alloy Castings, to cast cylinder heads, crankcase and other parts and moved premises once again, to Stourbridge Road, Halesowen. Contracts were won to supply many thousands of 405cc Sprites to USA importers American Eagle (McCormack International). Further models were exported to Australia and a few to Northern Europe.

Then, suddenly, it all went wrong for Sprite. The mini trials motorcycle craze was soon over, knocked aside by Bultaco, joined by Ossa and Don Smith-developed Montesas, then American Eagle collapsed leaving Frank Hipkin’s empire beached. Motorcycle production petered out and finished and, despite a brief flurry as the new Redorne was launched, the Halesowen factory closed. However, the foundry and repetition machine shop remained in business.