Sunbeam 1912-39 and 1947-64 UK

Born at Ludlow, Shropshire in 1836, John Marston was educated locally at St Lawrence’s Grammar School, then Christ’s Hospital, London before signing an apprenticeship agreement with Edward Perry of Richard Perry, Sons & Co, of Wolverhampton. Established in 1790 at the Jeddo Works they were Japanners and tinsmiths.

Following his apprenticeship, Marston – in c1859/60 – bought a rival Japanners and tinsmiths business with premises at nearby Bilston. He married Ellen Edge in 1865 and their first child, Charles, was born two years later. John and Ellen had 10 children of which eight survived infancy. Following Edward Perry’s death John Marston bought the firm Richard Perry, Sons & Co and soon expanded the business.

Significantly, Charles Marston joined the business in 1885, aged 18, working part-time initially while studying for science and business qualifications at Mason College (later became Birmingham University). Until his 21st birthday Charles received no wages from the business.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

As a family, the Marstons actively supported their local church and John Marston served locally in a number of public roles including as a councillor for his local ward. Another family pursuit was the rapidly growing activity of cycling. Circa 1888 company works foreman William Newill oversaw the assembly of their first cycle with low frame to suit John Marston. Superbly finished in deep black enamel with gold leaf, folklore claims Ellen Marston was attracted to the way sunlight reflected from this stunning cycle and named it Sunbeam. The name was registered as a trademark. Marston, pleased with this first cycle, gave Newill a company partnership and Sunbeam cycle manufacture began.

Sunbeam’s timing to start cycle manufacture was perfect as the pursuit was gaining huge popularity. The cycle side of the business grew, and gained more workshop space at the Paul Street premises, which became known as Sunbeamland. They exhibited at London’s Stanley Show for the first time in 1889 with over a dozen cycles and tricycles. There they displayed their first patented cycle component, an eccentric chain adjuster fitted to a cycle’s bottom bracket. At the same time Mr J Harrison-Carter was working on a project that led to the famed Sunbeam oil bath chain cases.

A London office and showroom was opened in Holborn Viaduct and penny-farthing (ordinary) racer William Travers became a Sunbeam agent in London. Cycle development continued apace with ultra light racers and roadsters, a spring frame, the switch to Dunlop pneumatic tyres and by the 1893 Stanley Show the Carter-patented fully enclosed chaincase was displayed on some machines. William Newill evolved the concept further using the chaincase in place of the frame’s lower right chainstay. Instead it was soldered into the chaincase.

The rapidly growing business became John Marston Ltd in 1895 and Marston became one of Wolverhampton’s most influential businessmen, helped by his continuing involvement in local borough affairs. During the next few years further depots were opened including another in London and one each in Manchester and Edinburgh.

With cycling sales booming, Sunbeam made more and more components for their own cycles and for sale to rivals. But success was at a price – space – leading Marston to buy further premises in nearby Villiers Street where in 1898 John Marston established The Villiers Cycle Components Co to make and supply many components including pedals, freewheels, chainwheels and much more to the cycle trade. The famous ‘Little Oil Bath’ legend with its distinctive transfer was coined in 1899.

Although they had outwardly made no advance into the fledgling motor industry, clearly Sunbeamland had given it thought for in 1899. With Marston’s nod of approval, a team of four led by Thomas Cureton built Sunbeam’s first car – a 5hp single with solid wheels and exposed gear drive created in a redundant building in Villiers Street. A further prototype followed, then the company announced it was building voiturettes and a 6hp twin-cylinder car was built into prototype form.

Known as the Sunbeam-Mabley the voiturette was often cruelly described as a powered Victorian sofa or loving chair! Designed by Mr Maberley Smith – who developed it but never put the concept into production – its concept passed on to Sunbeam. With its wheels laid out in diamond fashion and the driver sitting behind the sideways positioned passenger it was certainly odd but at least its 327cc De Dion engine was conventional. Production level reports vary but suggest between 100 and 350 were built – however, by 1904 the last few struggled to find buyers.

With professional car man Thomas Pullinger – late of Darraq – joining Sunbeam in 1902, car development followed more conventional lines. First with a French 10-12hp four cylinder Berliet assembled under licence then the creation of Sunbeam designed cars. In 1905 the car division was hived off to create The Sunbeam Motor Car Company Ltd enabling the raising of cash for development and establishing production lines.

Although out of the remit of this feature it’s worth mentioning the STD (Sunbeam, Talbot, Darraq) combine which was created in 1920 and later collapsed in 1935, opening the way for a takeover by the Rootes Group.

While all this was going on, Sunbeam continued building massive numbers of their quality cycles and Villiers cycle components, thoughts only briefly strayed to motorcycles. James Morgan patented a development of the ‘Little Oil Bath’ chaincase for motorcycles and at least one Motosacoche cyclemotor type unit was installed in a Sunbeam cycle. Tragically, a worker was killed while riding the machine and John Marston would have nothing more to do with motorcycles…

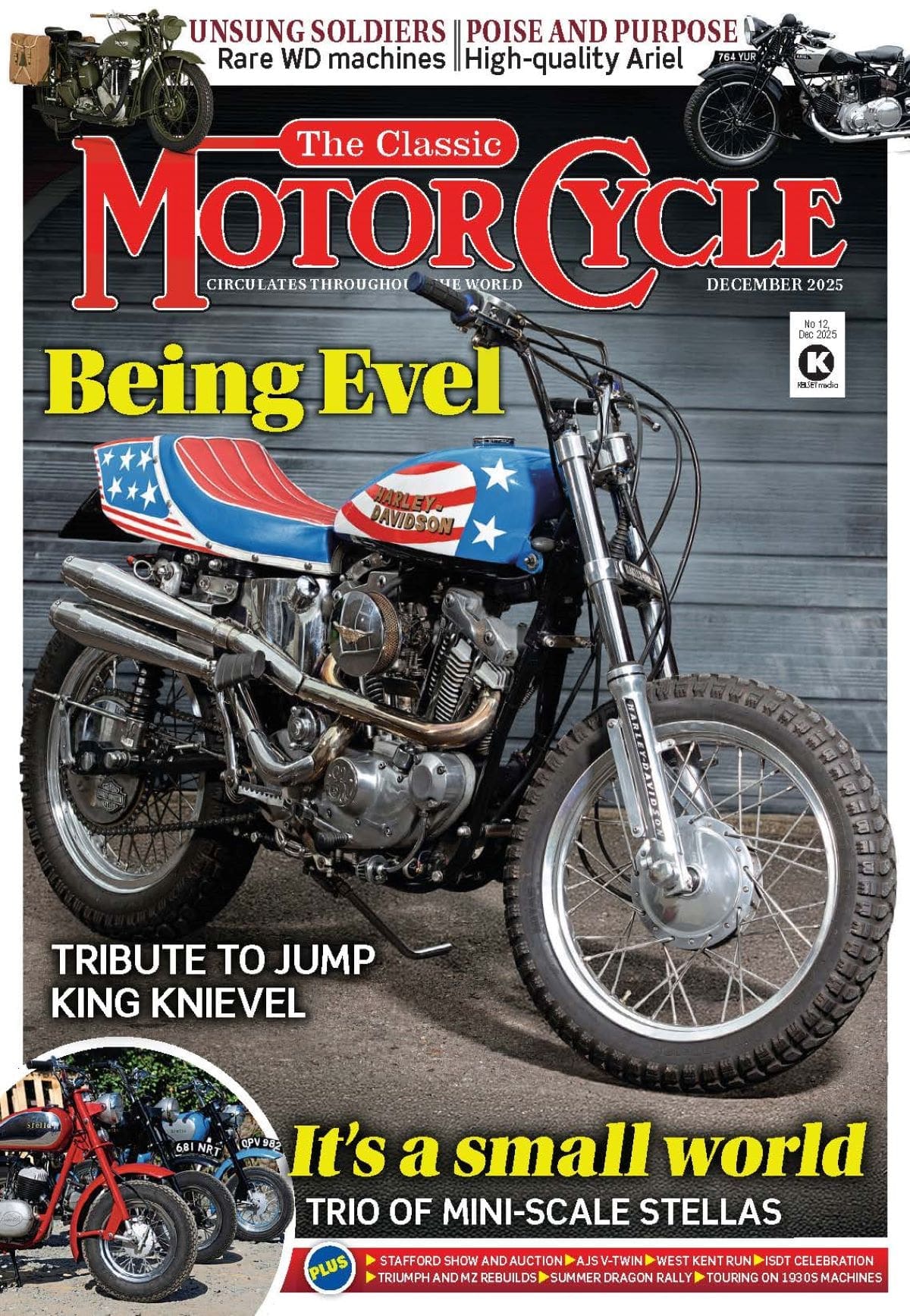

With a change of heart, Marston employed ex-JAP and Rover man John Greenwood to design a practical and profitable motorcycle. In typical Sunbeam fashion it was smart, well made, superbly painted and thanks to Harry Stevens – one of the Stevens brothers who founded AJS – it was mechanically sound. Although the first models weren’t offered until 1912, the launch model 349cc side-valve single cylinder motorcycle was near perfect straight from the box.

First models costing 60 guineas (£63) were finished in luxurious black enamel to frame, mudguards and detail cycle parts, while the tank was painted green with ‘The Sunbeam’ legend on silver panels. Although Sunbeam were more than familiar with the quantity production of cycles, motorcycle manufacture was little more than a trickle of hand-built models rolling through the factory gates.

Marketed with a seemingly negative approach, prospective customers were advised to add their name to the factory waiting list. Customers were assured of a quality product and all models were sold through or via Sunbeamland’s cycle depots across the UK who offered full factory backup – a gentlemanly way to conduct business for a gentleman’s motorcycle.

Sixty guineas bought a machine with all chain drive employing Sunbeam’s famed ‘Little Oil Bath’ chaincase, two speed-gearbox, clutch, forks built under Druid patent, rear stand, carrier and tool bags. For the 1913 season the Sunbeam gained a number of minor detail modifications, especially to the chaincase, lost some nickel plate and for the first time the tanks gained the famous black enamel finish with quarter-inch gold leaf lines and again bore the legend The Sunbeam.

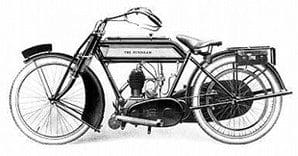

The company continued supporting reliability trials and began entering hill climbs. Designer John Greenwood was ably supported by youngsters Tommy de la Hay and Howard Davies. In mid 1913, a 6hp V-twin intended for sidecar work joined the 350. Powered by a 770cc JAP engine it employed a three-speed sliding pinion gearbox, again with a clutch and kick-start, chain driven magneto (instead of gears as with the single) and of course the Little Oil Bath chaincase.

Strong sales encouraged the motorcycle team, again led by Greenwood, to design a factory built 500 for the first time. Drawing on his past Rover experience Mr Greenwood used an 85 x 88mm bore and stroke, which was later to serve other big British singles so well including the post-WWII BSA 500cc Gold Stars. Although Sunbeam’s basic engine design was similar to the 350, it was improved to obtain more power than many rival 500s. Its Druid style forks were again revised with straight front tubes and curved rears, a three-speed gearbox (as used for the 6hp) was employed and chaincases were cast aluminium.

Priced favourably at 66 guineas, it was an ideal choice for touring and sporting riders along with sidecar men, especially those who rode solo during the week and hitched on a sidecar for weekend outings. The 500 (31⁄2hp) proved an instant hit in reliability trials including long distance events in the UK, sur le Continent and down under in Australia.

Following a bit of a dispute after the 1914 Scottish Six Days Trial works employee and rider Howard Davies was fired but fortunately re-employed before the IoM TT where he finished equal second with Oliver Godfrey (Indian) to winner Cyril Pullin’s Rudge. A super result for Sunbeamland’s first foray to the Island.

While Vernon Busby of AMAC carburettors, along with Sunbeam employees Charlie Nokes, de la Hay et al flew the company flag with vigour, a new man quietly joined the company as a mechanic. Charles Dance learnt his trade working on ploughing and traction steam engines and soon proved a super mechanic, fitter and rider. Dance was to prove a man for whom winning was everything and to be runner-up was nothing.

As the world sped towards WWI, Sunbeam focused development effort on the 3½hp and 6hp models. Two years proved a long time in the life of a motorcycle at the Wolverhampton works and the successful 2½hp model was quietly forgotten. Although Sunbeam continued limited motorcycle production in early WWI (complete with optimistic catalogues for 1915) the main effort concentrated on making radiators for aircraft and vehicles for the military.

Despite this essential work, Sunbeamland found time to supply a small number of motorcycles for military applications. These included 6hp V-twin models with either 770cc JAP or 795cc Abingdon King Dick designed engines for both British and Allied use – likewise the favourite 31⁄2hp side-valve single. A longer stroke (85 x 96mm) 4hp model – which performed well in reliability trials run during the early war period – was supplied predominantly to the French forces and a delightful 996cc MAG engined V-twin went to the Russian and Allied forces. Some regard this machine with disrespect as they consider its engine too low in the frame – others think of it with favour. Military Sunbeam models were often coupled to sidecars, including ambulance sidecars.

A 1916 catalogue was issued – in truth an update of 1914 and 1915 issues – and limited civilian production continued. On 3 November 1916 the Ministry of Munitions ended civilian motorcycle manufacture for the duration of the remainder of the war.

Despite weathering WWI, behind the scenes Sunbeamland plummeted into deep gloom before 1918 had hardly opened. Of John Marston’s sons, Charles headed up Villiers, Jack – a lawyer – had already died and Roland (expected to succeed John Marston as MD) passed away suddenly in February 1918. John died a few days later and his wife Ellen during March 1918. Suddenly, Thomas Cureton, who was approaching retirement age, found himself MD of a company that had lost leadership and was saddled with death duties.

With Armistice signed on 11 November 1918, the world and Sunbeam should have faced a more certain future. History proves neither did. Over the next few months, Charles Marston became more unsettled, despite having worked hard to enlarge Sunbeamland’s Villiers proprietary parts and engine business. This, coupled with death duties and tax liabilities along with his dissatisfaction of products from Sunbeam, encouraged Charles to sell his shares to Explosives Trades (a munitions conglomerate with money to invest). Turning his back on cycling and motorcycling, Charles Marston became an archaeologist and archaeology writer.

Then in quick succession, MD Thomas Cureton died, Explosive Trades merged with Nobel Industries and Sidney Bowers became MD. In the short term, this was good as Nobel Industries invested heavily in Sunbeamland and continued to do so until 1928 – additionally, Bowers and Sunbeam were well acquainted with each other.

The British Government authorised the restarting of civilian motorcycle production in January 1919 and Sunbeam soon recommenced with a range of 3½hp and 8hp models. Initially, models were similar to 1915 machines or those sold to the Allies but some renaming occurred, such as the TT Model, which became the 3½hp Sporting Model.

Fuelled by demob gratuities and an increased desire for independent transport, demand vastly exceeded supply and the added factor of inflation ensured motorcycles were highly priced and soon became even more expensive, suffering a series of hefty increments. The market place had changed too. No longer was it just moneyed gentlemen were buying the ‘gentlemen’s motorcycle’ but men from all walks of life – and the occasional lady too. And many didn’t just want a motorcycle, they wanted performance. Hindsight begs the question what else did Sunbeam expect, considering the exploits of George Dance et al. But, in common with rivals, they were surprised.

While Dance (whose race transport comprised a Cubitt car with his Sunbeams strapped to the running boards) was winning at practically every event he entered on his self built and prepared ohv ‘works’ Sunbeams. Aided and abetted by Greenwood, de la Hay and others, the factory was busy developing new models for 1920. Modifications included a new front fork, revised timing chest cover and reworked gearbox oiling.

With the IoM TT restarting in 1920, Sunbeam was ready. There were new works 500cc sidevalve racers with detachable cylinder heads for George Dance, Tommy De La Hay, Frank Townsend and privateers Reg Brown and Eric Williams. Dance was Sunbeam’s favourite but despite a good start, the TT was never to be his race. After setting a cracking pace he dropped out on lap three, handing over the lead to Norton man Duggie Brown, which he held until lap five when de la Hay took over. Sunbeams not only won and were third and eighth but Dance set a new record lap of 55.62mph.

As the season closed, and in spite of high prices, Sunbeam offered a mouth-watering range, including a new 31⁄2hp Sporting Solo Sunbeam TT Model with a sliding pinion gearbox. Although small it was a crash box in the real meaning of the term. Later, this was adopted across the range. The press then christened Sunbeam ‘The Rolls-Royce of single cylinder motorcycles’; further kudos fans revelled in and doubters doubted.

On the horizon sales were to falter, thanks to tightening purse strings that would see prices tumble – however, not before Vailati won the Italian GP. Reg Brown and others won lots of reliability trials golds and George Dance just went on winning, including 18 wins from 18 starts at Clipstone and a FTD of 90.94mph, 14 wins from 14 starts at the Norfolk Open Speed Trials and a string of 350/500cc records at Brooklands.

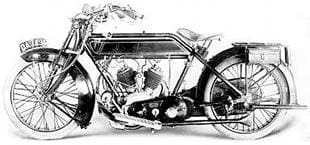

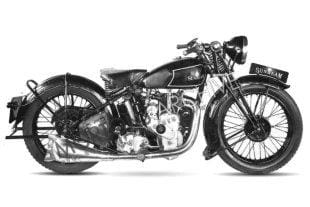

For the 1922 season two new models were listed, which were to become ‘standards’ from Sunbeam. Its engine developed from the 1921 French GP-winning Sunbeam, the immortal 492cc (77×105.5mm) Longstroke was initially marketed as the TT Model and known as or later marketed as Model 6, Light Tourist, Light Solo and 3½hp. The other newcomer was the 599cc (85×105.5) Model 7 or 4½hp. Intended for sidecar work, it comprised a Longstroke bottom end with an 85mm barrel and it had a leaf spring front. Although built from existing parts, towards the end of its run in 1932 it has the honour of being the last flat tank motorcycle in UK production.

Sunbeam enjoyed another good racing season in 1922, the pinnacle being Alec Bennett’s Senior TT win, over seven minutes ahead of Walter Brandish’s Triumph, with a fastest lap and new record of 59.99mph – and the last TT win by a side-valve machine. However, all wasn’t well behind the scenes. Bennett wanted to be number one works rider while the established de la Hay viewed the situation differently, won the day and Bennett left for Douglas.

Little changed for the 1923 season models, although the rack and pinion gearbox was all but phased out (fitted to the 4½hp only). However, a new 70x90mm 347cc side-valve was unveiled, giving the touring Model 1 and sporting Model 2 that in stripped form was also sold as a TT Model.

Although Les Randles won the 1923 Amateur TT on a Longstroke and George Dance continued sprinting to success, for the rest it’s a season best forgotten. The ohv 350s bust and the side-valve 500s were suddenly outpaced by a new breed of ohv rivals. Sunbeam hit back by hiring Graham Walker (yes, the Graham Walker) as their first dedicated competition manager – previously the role and been filled by staff on a part-time basis.

For 1924 Sunbeam worked hard to keep on pace. Model numbers replaced names (a system which continued until 1936). Model 1 = Touring SV 350cc Model 2 = Sports SV 350cc Model 3 = Standard SV 3½hp Model 4 = Standard SV 4½hp Model 5 = Light Solo SV 3½hp* Model 6 = Longstroke SV 3½hp Model 7 = Speedman’s SV 4½hp * Note the 499cc Model 5 was followed by a variation of the 492cc longstroke for the 1927 season.

During the season Sunbeam launched its first ohv models with dry sump lubrication and hemispherical cylinder head design. The 347cc (70x90mm) machines were marketed as the Model 8 (standard) and Model 10 (sprint) while the 493cc (80x98mm) versions were the Model 9 (standard) and Model 11 (sprint). As appropriate these were marketed variously as Model 8, Model 80 (racing), TT and continued as the Model 8 until 1938 while the 500s included the Model 9, Model 90 (racing), later Model 95, TT and continued as the Model 9 until 1938. Both 350 and 500 were continually updated over the years.

The specialised sprint models, with central exhaust port, were a problem for the frame making department, resulting in twin down tubes to engine plates to facilitate fitting of the exhaust pipe. These central exhaust port versions were dropped as interest in sprinting waned and then effectively ended as the sport was banned from public roads in 1925 (until this time sections of road could, with permission, be closed for sprinting or hill climbing). This change in legislation also ended George Dance’s impressive competitive career.

To an extent Sunbeam’s racing programme went on hold during 1924, with no true works TT entries, although they continued to enjoy success on the continent, including wins for Walker (Senior) and de la Hay (Junior) in the Swiss GP. Little changed for the 1925 season models, although drum brakes first fitted to ohv machines became standard across the range. Behind the scenes Sunbeam had been working hard on an ohc design – some claim rumours of this work encouraged Walter Moore to develop his concept of the ohc theme, which became the Norton CS1.

Following exhaustive testing, the Sunbeam ohc models were to be ridden en force in the 1925 IoM races. On Junior race day, the work riders turned out on ohv racers but it wasn’t to be Sunbeam’s year in the Island. Works boys Dance, Randles and Italian Achille Varzi retired, Bert Tetstall (standing in for injured Tommy Spann) toured in ninth and significantly a young Charlie Dodson, on his privately entered ohv model, was eighth.

In the 1925 Senior, seizures ruled the day, reducing Dick Birch, Dance, Spann, Harold Mylchreest and Walker to spectators. However, Randles sixth, Charlie Waterhouse (well known in Welsh racing circles) seventh, Varzi eighth and Tetstall 10th flew the factory flag. The new ohc models struggled in the French GP; significantly, rather than invest and develop the concept, Sunbeam dropped ohc engines in favour of the proven ohv design. Some observers regard this as a turning point and the start of Sunbeam’s downwards slide, citing the investment Velocette were making and Norton were soon to make as the path Sunbeam should have followed.

Despite the Sunbeamland doom and gloom, Sunbeam continued to make top quality motorcycles for those who could afford them, sales remained sound – and the ohv models were quick. The range was updated in detail for 1926. The company enjoyed modest trials success, and some continental success including wins at French and Hungarian GPs but little luck in the 1927 IoM TT races.

For 1928 designs were updated in both detail and frame design; notably, front forks were strengthened. Behind the scenes, Nobel Industries combined with Brunner, Mond Ltd to form Imperial Chemical Industries (ICI) and an ICI director joined the Sunbeam board. However, Bowers and Jones (general manager) effectively remained in charge but worry clouds began drifting over Wolverhampton.

With much work by George Dance and his team of enthusiastic helpers, the 350 and 500cc ohv racing Sunbeams were getting faster. Enjoying many continental wins including German and Belgian GPs for Dodson, Sunbeam were again riding high, although Walker had moved to Rudge. All five Junior Sunbeams retired and leading Senior TT Sunbeam rider Dodson crashed in atrocious conditions to remount and complete his ride home for a place rather than a win. Or so he thought…

Later in the lap he passed a stationary Walker on the Mountain and went on to win; the factory secured the team prize too. A result for new major Sunbeam shareholders ICI, who also owned Amal carburettors – but ICI didn’t seem that keen to make capital from Dodson’s win.

Mechanically, Sunbeams were updated for 1929. Visually they were dramatically altered (except the 599cc side-valve model), switching to saddle tanks. Tradition was maintained with the luxurious all black enamel finish. Charlie Dodson again took the Senior TT for Sunbeamwith Alec Bennett, who’d returned to the Wolverhampton factory for his 500cc IoM mount, second. Continental success continued and outwardly Sunbeam seemed to be weathering the depression.

For the 1930 season range it was a case of more of the same, although briefly a Model 90-based speedway model was included. Sadly for Sunbeam the new decade got off to a poor start when Sidney Bowers stood down as MD through ill health and ICI moved accountant Graham Bellingham in as his replacement. At the TT, Rudge swept the board in what was Sunbeam’s last works supported Island visit.

Sunbeam continued to make quality motorcycles but their style was cramped jointly by the depression and ICI through Bellingham. A new 344cc ohv single (the Model 10) was introduced for the 1931 season but for the rest it was a case of more of the same. Sunbeam, like many, struggled for sales. Trade pressures were putting dealers out of business, others were heavily discounting models, the trimmed down catalogue was for the first time priced in pounds sterling rather than guineas and John Marston Ltd was described in publicity material as a subsidiary of ICI. True, but not what all gentlemen (and ladies) wanted to hear.

Continuing on a depressed note, Sunbeam withdrew from racing, although privateers and dealer sponsored riders including Vic Brittain continued to campaign the Wolverhampton machines. The factory still supported trials competition but no longer needed the legendary George Dance, who briefly worked for Diamond before setting up as a market gardener.

During the summer, Sunbeam announced a two-stroke range; the fact they were boat outboard engines was and still is a relief to the diehards.

Along with rivals, Sunbeam felt more buoyant in 1932. Alongside the many detail improvements across the range, Sunbeamland introduced a constant mesh four-speed gearbox.

In an effort to raise a little more cash, much of their vast stock of parts for older models was sold to George Lathe – who much later scrapped some of this stock. Sunbeam also in effect built obsolete models out of surplus parts which were sold at competitive prices through some outlets.

Despite having officially withdrawn from racing, ‘works’ prepared models were available to chosen privateers; but sadly, while places were theirs for the taking, pushrod Sunbeams were no longer a match for the rising tide of cammy models from rivals.

Peter Bradley continued to score golds in the annual ISDT with his outfit. Roadster model improvements continued with the Model 95 replacing the Model 90 and the 250cc Little 95 replacing the Little 90. Reading between the lines, it is evident consolidation rather than development was the keyword in Wolverhampton. And as history tells again and again, this only leads to a marketing slowdown.

An era ended in April 1934 with the retirement of John E (Cherry) Greenwood, engine and often machine designer since 1913.

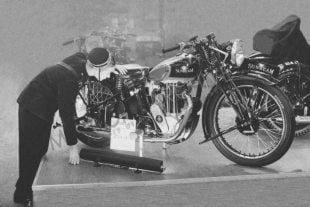

At the autumn London Show, Sunbeam unveiled their first high camshaft model, the George Stephenson designed ‘250’. Many consider Sunbeam skimped on development and production standards slipped for this model. It lasted one season, replaced by an update of the older so-called long stroke 250. For 1936 cradle frames were introduced and Burman gearboxes in place of Sunbeam’s own box across the range except for the 600. Alongside this, ICI, unhappy with the small level of profit from Sunbeamland, also placed the business on the market.

Behind the scenes, AMC bought Sunbeam, although ended up with much less than they’d hoped. Production was transferred to London with the Wolverhampton staff being switched to radiator manufacture. George Rowley, who was about to move from Plumstead to Wolverhampton until Donald Heather wised him up, oversaw transfer of production, the scrapping of much Wolverhampton machinery and sadly to us historians, much valuable literature.

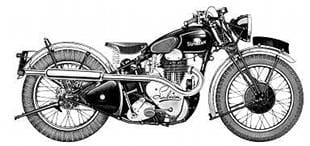

In effect, AMC produced a 10-model range for 1938 with only detail changes, but behind the scenes work was under way on a new 248-598cc high camshaft range. Along with revised engine dimensions, the frame was modernised. Finish remained good, although some purists hated the brand Sunbeam scripted on the timing chest cover, not in keeping with the perceived Wolverhampton Sunbeam image. In standard road trim, the larger models, while performing well, were incredibly heavy. AMC had the courage to expand the range to include sports and competition models as appropriate and Geoffrey Godber-Ford won a handful of trials cups – success on which AMC tried to capitalise.

Looking forward, spring frames of swinging arm design were unveiled in the summer of 1939 but the onset of WWII scuppered the project. It’s doubtful any – or, if they did, only a handful – rolled off the production lines.

Quite what happened next is unclear. Facts tell us that after protracted negotiations, BSA signed an agreement to purchase for a hefty sum the Sunbeam brand name and much tooling; press announcements were made to this effect on 23 November 1943.

It’s also known BSA never bothered to collect work in hand, jigs and tooling for the high-camshaft models. Clearly the new company, established by BSA with James Leek as MD and Bernard Docker as chairman, weren’t interested as they had other plans for the brand. These centred round a machine based on a captured 750cc R75 BMW. However, what events led to this thinking is where we could, and some do, enter the realms of speculation. Did BSA buy the Sunbeam name for a planned new motorcycle, did they buy the brand then develop the model or did it all just happen? Who knows? Whatever, it’s dangerous to shape history to suit.

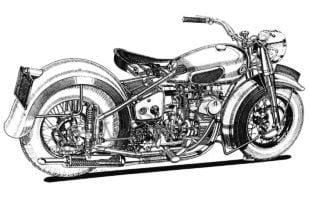

Renowned engineer Erling Poppe had spent recent years in the four-wheeled world, which certainly influenced his final concept for his Small Heath masters; so too did established BMW design. Rolling chassis design, including telescopic front fork and brakes, pancake dynamo design, shaft drive and many other details, owe much to the R75. But the inline OHC twin cylinder engine was car-like, albeit air-cooled. Hiccups and problems including vibration and handling issues beset the development and even early production of the new BSA, named the Sunbeam S7.

Eventually, by spring 1948, models were gently flowing to the dealers and a year on 2500 had been built. Unfortunately for BSA, almost no parts were standard ‘off the shelf’ BSA components, making manufacturing costs high. In March 1949 BSA announced a new Sunbeam coded the S8, with conventional sized wheels and narrower mudguards. Two months later the fat wheeled S7 was replaced by an updated model launched as the S7 de-luxe. With minor updates, the S7 and S8 continued in production until 1956, although models remained on sale with some dealers until 1958. A couple of further S7/8 based prototypes were built but never put into production.

It’s popular in some quarters to knock the post-WWII Sunbeams, and it’s true they owe nothing to the brand’s Marston origins; but they are distinctive, pleasant-natured motorcycles. Thanks to a superb spares back-up, they can be kept going forever, and they’re different. But watch out for the BMW-like torque reaction, which tries to twist the machine over to the right under hard acceleration from low speeds.

That should have been the end of the story, but thanks to Edward Turner and Charlie Salt, it wasn’t. The duo came up with a pair of scooters which, with badge engineering, were sold as the Triumph Tigress or BSA Sunbeam. The smaller engined 175cc single cylinder two-stroke model’s engine was based on the BSA Bantam unit, while the larger model was powered by a newly designed 250cc OHV twin unit. Announced in late 1958, the scooters remained in production until 1964. Models were the BSA Sunbeam B1 (175cc), B2 (250cc) and B2s with electric start. Triumph versions were the Tigress TS1, TW2 and TW2s. All were sound scooters but unfortunately Lambretta and Vespa had already secured the lion’s share of the market place and sales weren’t up to the director’s expectations.