David Wright remembers a remarkable motorcyclist who took part in trials and displays; rode the largest capacity Britbike of its time, and worked behind the scenes for decades for grassroots clubs and the national ACU…

Forty years ago in 1973 the compulsory wearing of crash-helmets was forced upon the motorcyclists of the United Kingdom. To the majority it did not present a problem, for they were already wearing them, but for a few the new law had a much greater effect upon their motorcycling lives. One of those few was Doris Lowe.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

Many have heard of lady competition motorcyclists of the past such as Marjorie Cottle, Olga Kevelos and Mary Driver for, just as in other fields, successful sporting endeavour brings fame and headlines to the few. However, there have been other female motorcyclists who have been important to the motorcycling movement through the years, but who received little recognition.

Amongst those unsung ladies were many involved with the organisation and administration of the sport of motorcycling – working in the background so that others could compete. Most restricted their activities to local club level, for the sport was traditionally run by men in its higher echelons. Few of those ‘back-room’ ladies got the opportunity to climb the organisational ladder and participate in the affairs of the sport at the highest level, but one who did was Doris Lowe.

Born Doris Florence Clarke in 1911, the daughter of one of Luton’s earliest garage proprietors and with four brothers for company, it would be easy to jump to the conclusion that she had the ideal background to emerge as one of those fairly rare characters – a lady motorcyclist. But that wasn’t the way of things and her upbringing and early life was quite conventional. With a musical mother bringing a strong influence to family life, Doris became an accomplished pianist and, with an academic inclination, moved into a lifelong teaching career at the early age of sixteen.

Life took its steady course until the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939. Then she quickly found herself involved with the multitude of children evacuated from London. This involved wiping their tears, organising their accommodation and dealing with a hundred and one other tasks needed to settle them into their new lives. After that, she had to set-to and teach them in heavily overcrowded classes.

Although only 30 miles from London and with major engineering concerns like Vauxhall Motors, Commer Cars, Kent Instruments and Percival Aircraft in the area, Luton was subject to relatively little wartime bombing. However, defence precautions still had to be taken. Doris continued to teach during the day, and regularly put in several nights a week on telecommunications duties at the local ARP (Air Raid Precautions) headquarters. In the early years of the war, many of the telephone messages received were taken to their final destinations by part-time motorcycle despatch riders. As petrol supplies dwindled and those same motorcyclists joined the fighting forces, a team of young lady pedal-cyclists was recruited to act as message bearers in their stead.

Being of a confident nature and slightly senior to these eighteen and twenty year olds, Doris was placed in charge of the fleet of two-wheeled messengers. Only then did it come to light that she could not ride a pedal-cycle! However, after a few wobbly practice sessions, the necessary skills were acquired.

Her reward for acquiring those two-wheeled balancing skills came with an order to learn to ride a motorcycle. It was an instruction that was to change her life, although she admitted to being scared stiff at the time. Several machines had passed through her brothers hands before the war but, like most young ladies, she considered them to be noisy, nasty things. However, there was a war on and people did as they were told in such matters so, learn she did.

Her instruction in the art of motorcycling was basic but effective. Taken to the top of a long hill of fairly shallow gradient, she was pushed off with a dead engine and told to treat it like a pedal-cycle. For the next lesson the engine was started, finer points of control were explained and off she went under gentle power. It then became a case of: ‘once they got me on they couldn’t get me off.’

Well and truly hooked by those first experiences on a powered two-wheeler, Doris began to look around for a machine of her own. This was no easy task in wartime but in 1944 she acquired a 1934 Francis-Barnett Cruiser that, on the very limited petrol supplies available, was ridden as much as possible on ARP duties. As a result, much of her early riding was carried out in the total blackout of wartime nights – hardly the ideal learning conditions for a novice rider.

Come peacetime, Doris acquired the first of a series of Royal Enfields. It was an ex-WD 350cc, with an unknown war-time history but still finished in combat khaki, and it offered a little more performance than her Francis-Barnett. There followed more miles on two wheels that provided a broadening of personal horizons and motorcycling experience, albeit within the very limited ‘basic’ petrol allocation available to civilians in those still austere post-war years.

With the end of petrol rationing in 1950, freedom of the road truly arrived, and for those who could afford the cost of 3/- (15p) a gallon it became a case of motorcycling all the way. Doris was putting in her share of miles and the ex-WD bike was replaced by a new 350 Royal Enfield Bullet with telescopic forks up front and swinging arm rear suspension. In her case the luxury of modern suspension was appreciated for the increased comfort as much as for the improved road holding that it offered. Doris recalled that she could then: ‘go through potholes, rather than have to go round them.’

Having really caught the motorcycling bug, she joined the local Dunstable and District Motorcycle Club, quickly involved herself in their sporting and social activities and thus found even more time being taken up by motorcycling. It wasn’t long before her obvious enthusiasm resulted in election to the post of club secretary. It was her first step on the organisational ladder and she began to learn the ways of the Auto Cycle Union (ACU), the body that governed motorcycle sport in Britain and to which almost all motorcycle clubs of the time were affiliated.

Still a member of what in peacetime had become the civil defence, she participated in occasional displays on borrowed army Triumphs. Jumping off ramps, riding through hoops and other obstacles were all part of the routine. The White Helmets they may not have been, but there were plenty of scrapes and near misses to enliven proceedings. Ordinary spare-time civil defence duties continued but were somewhat less spectacular.

Like many motorcycle clubs of the 1950s, the Dunstable Club was buoyant as it rode on the back of UK motorcycle sales which reached their all-time peak in 1959. As well as having an active social calendar the club organised several trials and scrambles each year. Doris was always there in the thick of things; obtaining consent for land use, applying for permits, advertising events, acting as secretary of the meeting, observing, marshalling, lap-scoring, dealing with results. They were just some of the jobs she did whilst still carrying out the duties of club secretary.

|

Royal Enfields on ..

More eBay old bikes below |

It was during the 1950s that she decided it was time that she joined in the sporting side of riding and enjoyed a bit of muddy fun. She acquired a 125cc Francis-Barnett in trials trim and this was soon brought into service. It provided the means to compete in the traditional type of trials that wound themselves around perhaps 40 miles of local lanes, linking as many as possible with muddy off-road going and throwing in 40 or so observed sections for good measure. This went on for several years and although she never won anything, the enjoyment was long-remembered. In later years, Doris reflected that perhaps 40 years of age had been a bit old to start trials riding!

Still making daily use of the 350 Bullet on the road, it eventually gave way to another Royal Enfield from her favoured local dealer, BG (Bert) England of Luton and Dunstable. This time it was a step up to a 500cc Meteor Minor with 17-inch wheels and, as usual, a single seat because solo motorcycling was the name of the game for this rider, and passengers were not welcome. If a bike could only be obtained with a dual seat, then off came the pillion footrests.

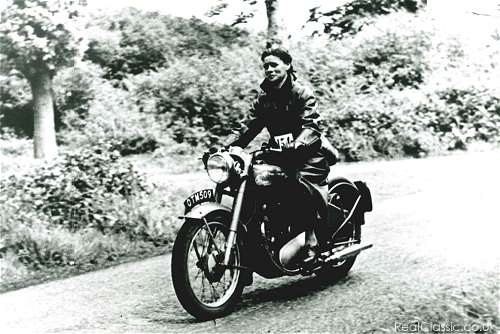

Still working as a schoolteacher and surrounded by hordes of people during the day, the solitude available on the bike was carefully guarded. Mind you, although Doris may have travelled alone, wherever she rode the bike in the Luton area she was noticed and recognised. Known to hundreds of schoolchildren and their families, ‘Miss Clarke’ as she was at the time was a familiar figure on the relatively uncrowded local roads. With hair drawn back (never covered), waterproof coat, skirt, stout shoes and shoulder bag, she travelled everywhere by motorcycle.

Doris lived out in the country at Breachwood Green, where public transport was almost non-existent, so her journey to and from work meant a five mile ride each way over minor lanes. While she normally did it on the Royal Enfield, if there was frost or snow about, the lighter and more manageable Francis-Barnett trials bike would be brought into service. Whatever the weather, two-wheeled travel was always enjoyed. She relished the independence that it gave, and found that it kept her fit, healthy and free from the coughs and colds that troubled many other people.

A woman riding a motorcycle in the 1950s was a far more conspicuous sight than one would be today. Firstly on account of the general rarity value and secondly because she would not be disguised by an all-enveloping helmet like present-day riders have to wear. Although she may not have been aware of it, Doris became something of a minor local celebrity with her stylish, all-weather riding, and this resulted in an interview with a reporter from the local newspaper. When he suggested to her that motorcycling wasn’t much fun in bad weather, he received the slightly scornful reply of: ‘If you’re born in England you ought to be able to stand up to England’s climate.’ Whether the English were born to be propelled through the worst of their weather at 60mph or more was not thought worthy of mention.

————-