The 498cc Porcupine is a rare racer indeed. This parallel twin, which first took to the track in 1947, was an out-and-out Grand Prix machine. There was no roadgoing equivalent to the E90 and E95 racebikes. The engine was an astonishing engineering achievement – made even stranger by its unusual gestation during the Second World War.

The Porcupine was the brainchild of Joe Craig, who is more famous for developing Norton’s racing singles. Craig’s concept was made metal with help from AMC’s development team which included Phil Irving and Vic Webb. However, when this team started the project they were building a supercharged engine, hence the unusual layout of the engine in the frame.

Supercharged multi-cylinder engines had begun to threaten the single cylinder racers’ supremacy towards the end of the 1930s and, indeed, AJS themselves went down this road with their fearsome water-cooled V4. Fast yet difficult to handle, the latter had demonstrated that horsepower bought at the expense of excess bulk and weight was not the answer, so the designers’ thoughts turned to a twin.

Laying the cylinders horizontally with their heads facing forwards would ensure adequate cooling and a low centre of gravity, while at the same time providing room for the blower above the unit construction gearbox. When supercharging was banned at the end of 1946, the Porcupine’s design was too far advanced to be substantially altered, although the cylinder heads were revised to raise the compression ratio.

Laying the cylinders horizontally with their heads facing forwards would ensure adequate cooling and a low centre of gravity, while at the same time providing room for the blower above the unit construction gearbox. When supercharging was banned at the end of 1946, the Porcupine’s design was too far advanced to be substantially altered, although the cylinder heads were revised to raise the compression ratio.

The overall design was therefore inevitably compromised: if the team had known they were building a normally aspirated racer from the get-go, then they probably would have opted for a four-cylinder layout. Instead, a parallel twin was chosen as the best option to squeeze in the additional gubbins required for the supercharging system.

The 68mm by 68.5mm motor produced around 40bhp at 7600rpm. It used double overhead cams and overlapping hairpin-type valve springs. The main engine castings were of magnesium alloy with the single-piece, forged steel crankshaft supported by three bearings. Straight-cut gears took drive to a four-speed close-ratio gearbox, built in unit with the engine to keep everything compact. A powerful but complicated lubrication system used multiple pumps to ensure a consistent oil feed throughout the engine, which was positioned in the duplex frame facing forwards.

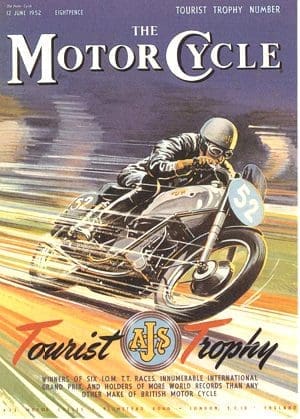

Typed E90, but dubbed ‘Porcupine’ because of its distinctive spiked cylinder head finning, AJS’ new challenger debuted at the 1947 Isle of Man TT piloted by Les Graham and Jock West. The Porcupine took some time to settle down and indeed never took top honours at the TT. That makes the cover of the 1952 TT Special of The Motor Cycle magazine all the more ironic – the two Porcupines finished a long way from the podium that year…

Two years later, in 1949, an ultimate victory was finally achieved as Graham won first place in the inaugural Grand Prix World Championships astride the Porcupine, a win that was to become AJS’ and Graham’s only major title.

Two years later, in 1949, an ultimate victory was finally achieved as Graham won first place in the inaugural Grand Prix World Championships astride the Porcupine, a win that was to become AJS’ and Graham’s only major title.

Many years later, AJS works rider Ted Frend – the first rider to win a race on the bike – recalled that carburetion had been the bike’s biggest problem, perhaps not surprising given that it had been designed for a supercharger, and over the years a bewildering number of different induction arrangements were tried.

The bike was also bedevilled by magneto shaft failure – the cause of Graham’s retirement from the lead of the ’49 Senior TT when just two minutes from the finish – a problem that would not be solved until chain drive for the magneto was adopted on the revised E95 engine. However, the E90 was more than good enough to secure two world speed records for AJS in 1950 at Montlhery.

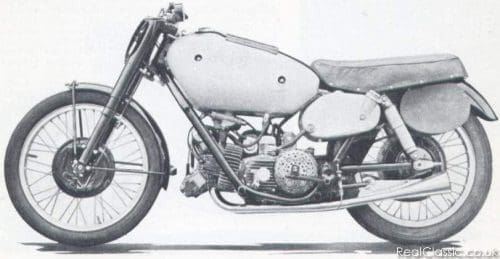

Introduced in 1952, the E95 engine had its cylinders tilted upwards at 45-degrees, an arrangement that called for a new frame, which gave easier access to the twin GP carbs, and featured a long underslung oil sump, and pressed-up crankshaft with one-piece connecting rods and roller big-ends in place of the E90’s one-piece shaft and shell-type bearings. In E95 form, the AJS racer weighed less than 145lb and output around 55bhp at 7600rpm.

Another new addition to the AJS team for 1952 was New Zealand star Rod Coleman. Coleman had first been given an E90 to try at the ’51 Ulster GP, and followed that up with a strong showing at the Grand Prix Des Nations at Monza.

‘In the race it was quite definitely faster than the Nortons and I had little problem getting past Geoff (Duke) and Ken (Kavanagh) with just three Gileras only a short distance ahead,’ Rod recalls in his book, The Colemans. ‘I did get with them and found again that the Porcupine was just as fast as the Gileras but was down a little on acceleration from the slower corners, but not by much. I was just beginning to think I had every chance of second place behind Milani when the motor stopped.’ The cause was yet another magneto shaft failure.

For 1954 Jack Williams took over the race team and the result of his brilliant development work was a much smoother, more reliable engine and a better handling bike. The E95 Porcupine and works ‘tripleknocker’ 7R3 gained new pannier-style fuel tanks, which extended down on either side of the engine thus lowering the centre of gravity and affording a measure of streamlining at the same time. A new second version frame lowered the bike still more. An AC fuel pump raised petrol to the carburettors, and a clever delivery system involved mechanics standing the bike on its rear wheel to prime the header tank for starting!

Bob McIntyre, Derek Farrant and Rod Coleman were the riders, the last providing the Porcupine with its best international results of the season, placing second in Ulster and winning the Swedish Grand Prix. Sadly, just when the E95 was at last proving its full potential, 1954 would prove to be the Porcupine’s swansong year as AJS withdrew from direct involvement in Grand Prix racing at season’s end.

Bob McIntyre, Derek Farrant and Rod Coleman were the riders, the last providing the Porcupine with its best international results of the season, placing second in Ulster and winning the Swedish Grand Prix. Sadly, just when the E95 was at last proving its full potential, 1954 would prove to be the Porcupine’s swansong year as AJS withdrew from direct involvement in Grand Prix racing at season’s end.

In total, just four complete E95 machines were built, plus one or two spare engines. With the exception of the Tom Arter machine (Arter’s E95 was originally meant to be a display bike in his showroom, but was discovered to be a fully functioning machine!), they were raced only by the works team and never offered for public sale. Because the number of AJS Porcupines is so scarce, each machine is well known with all 1954 models being accounted for (most earlier Porcupines were scrapped by the factory).

Until recently, this particular example had been on display for more than two decades, occupying pride of place at the National Motorcycle Museum in Birmingham, its motor having been overhauled by Team Obsolete Equippe.

The last Porcupine to sell at auction was the non-works, privateer-raced Tom Arter E95 Porcupine and it sold 11 years ago for £157,700, setting a world record for the price of a British motorcycle at auction. The bike you see here is expected to secure bids of $750,000 when it goes under the hammer at a Bonhams auction in California in the summer of 2011, and it’s conceivable that its sale price could even pass the million dollar mark.

That seems utterly amazing, given that the original Porcupine design was critically compromised from its creation – and although most of those flaws were fixed in the shape of the E95, this later version does not boast the E90’s iconic cylinder finning. The E90 did indeed win the first ever Grand Prix, but its continental competitors went on to much greater things – Gilera’s four-cylinder equivalent clocked up six world championship wins in the next seven years, while AJS struggled to make the Porcupine perform properly.

So perhaps if this E95 does sell for a stupendous amount of money, we should remember it not as the ‘world’s most valuable motorcycle’, but instead as the ‘world’s most expensive white elephant’…

Classic and British bikes like this one appear every month in the pages of RealClassic magazine. Our in-depth articles by expert and enthusiast authors reflect the old bikes we buy and ride in the real world: frequently fabulous; occasionally awful, but always interesting…