Yamaha were not following the herd back in the early 1970s. When some of their rivals were frantically developing sporty fours to replace their smoky, thirsty two-strokes, Yamaha went in a different direction technologically. It was a bit of a blind alley, but they were at least ploughing their own furrow. And that’s enough mixing of metaphors.

Their first four-stroke was the XS1, a 650 twin, which begat the XS2 that had an electric start and, like the XS1, didn’t handle or brake. And after a bit of work by Triumph tester and racer Percy Tait, the XS2 became the XS650 (briefly the TX650 in some markets), which did handle a bit, and stayed in Yamaha’s line-up until 1983.

Updating the parallel twin

There is a forgotten Yamaha four-stroke twin that came a few years after the arrival of the XS. It was called the TX750, and only lasted a few years. It was never officially imported into the UK, with most sales in the US and few sold in Europe.

Today one may wonder why Yamaha, who had a perfectly good and tough 650 engine, decided on a brand new-ish design for their first superbike. The XS was very capable of being made bigger and more powerful. Adding 200cc to the engine was to become the ultimate performance mod. The factory adding another 100cc to the 650 twin would have been the obvious thing to do.

But you have to remember that motorcycle design is about fashion. The British twins were being stretched to the limit, as their factories were forced to make things more and more powerful to compete with their Japanese rivals. As these limits were reached so vibration – that bugbear of the big twin – was the major issue. Quite apart from being uncomfortable to live with on long rides, vibration was shattering components and fracturing frames.

The XS650, despite being a 360-degree twin, was much smoother than rival machines from Triumph and BSA, thanks largely to everything being over engineered, as anyone who has tried to lift an XS650 engine by hand will testify to.

For their new 750 twin, Yamaha tackled vibration head-on. Norton had used rubber mountings to smooth out the Commandol; Yamaha would look at the engine itself.

There were two options for the crankshaft, as the 270-degree crank hadn’t been invented yet. They could go down Honda’s route and use a 180-degree crank, but that only really worked on smaller bikes with less weight to throw about, so a 360-degree crank it had to be.

To smooth everything out on a conventional engine would take heavy counterbalances on the crankshaft, which would work at lower revs, but was less effective the faster you went and also sapped power.

To smooth out their new twin, Yamaha decided to use a balancer system. This used a chain from the crankshaft to a pair of weights inside the lower part of the horizontally split crankcases. One weight was bigger than the other, and they rotated on opposite directions. This balancer, dubbed the Omniphase, cancelled out the vibration from the crankshaft.

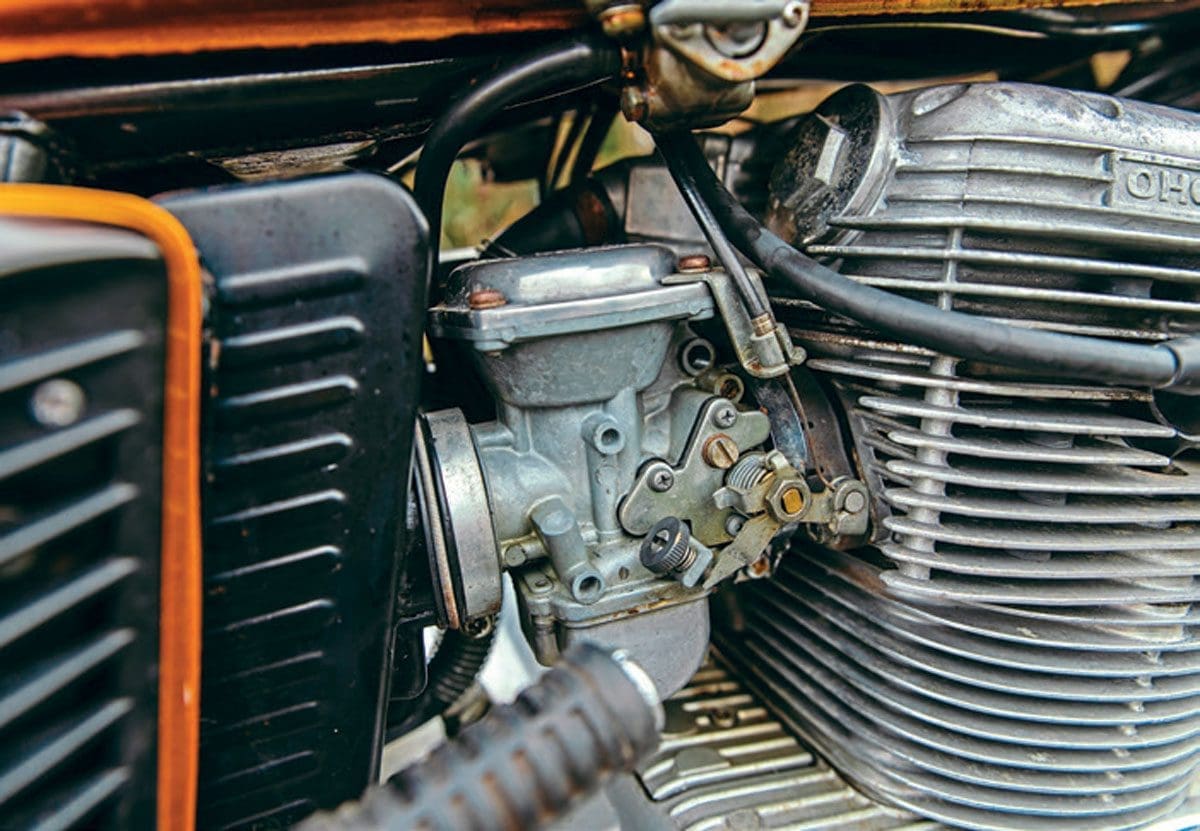

To the surprise of many – who had never experienced this kind of balancer system before, the method worked. The TX would have the sporty pretensions of a big British twin and be simpler to work on than a four, but would be just as smooth. Unlike the XS, the TX had a simple one-piece rocker cover over the four-valve head, with a nice, simple single overhead camshaft.

The engine, like a British twin or a Honda 750-4, was dry sump, with the tank under the seat. Ignition timing was under the generator cover rather than on the end of the cam as on the XS, which tidied things up considerably. The oil filter was hidden there too, a rather Heath Robinson affair featuring a box fed through two curved pipes.

The TX top end looked like a Honda four, with two cylinders cut off. They used the five-speed gearbox and clutch out of the XS, which were known to be good, but changed the starter arrangement already causing trouble on higher mileage XS twins for a new system, the starter motor turning the engine by chain through a three-stud sprag clutch.

Straight cut gears drove the clutch, as there were more than enough chains whizzing around in the engine by now, and anyway, that’s what the XS used. Having five gears was an almost unheard-of luxury for a British parallel twin fan.

The engine breathing system was ready for increasing emissions regulations, with the more unpleasant hydrocarbons that got past the short-stroke pistons into the crankcase recirculated and pumped back through the airbox to be toned down some more, rather than contaminating the oil. There were small louvres on the left-hand engine casings to help cool the generator.

The exhausts exited the engine through an arrangement that may be unique in motorcycle design. To balance the gas flow, the TX has a finned manifold bolted onto the head, as used on motor cars. Essentially it does the same job as the balance pipe on a British twin, but it looks much more space-age.

Meanwhile, away from the engine, other parts also showed promise. Brakes were probably adequate for the day, though the stainless front disc on the US and Australian models wasn’t of the hitting-a-brick-wall type. The few that made it to Europe got a second disc.

The instruments and switchgear were of excellent quality, and the electrical components were years ahead of their time. The bars were big and wide but not too high; appropriate for a bike designed as a super tourer. The seat was soft and comfy, and there were louvres on the side panel to provide a cooling draught for the oil tank and electric components.

Forks were basic and a bit soft, as were the rear shocks. The TX came with alloy rims, something of a first for a Japanese mass-market motorcycle. The TX was no lightweight, and was 120lbs heavier than a T140v Bonneville.

Yamaha had come up with a big, smooth, leak-free and powerful parallel twin with an electric start, well equipped and comfortable. What could possibly go wrong? Well…

What went wrong

There were three major flaws with the balancer shaft design, which, to be fair to Yamaha, was a concept nobody had tried before on a motorcycle. First, the chain drive to the balancers would stretch, slip, and then the weights would go out of phase, making vibration worse rather than better.

As well as stretching, the chains spinning those weights were non-adjustable and could break under the pressure of continuous high revving, spreading bits of metal through the engine.

Finally, the weights sat in the oil in the crankcase. Even if the balancer chain didn’t fail, then the balancers were likely to churn the oil into froth if the bike was ridden hard. This aeriated oil failed to lubricate the big ends and main bearings effectively, which had results you might expect, the lack of vibration giving little warning of impending bearing failure as it might have done on a BSA.

You rode the TX till it broke and then dealt with the consequences. As an added bonus, the now thin oil had no trouble leaking from gasket faces.

The starter motor chain which replaced the XS650 gear drive was prone to failure with pretty dramatic consequences – more so than those suffered by the XS which, at least, would simply go crunch and stop working.

Oil would leak past the seals on the shaft going into the contact breaker assembly, which was mounted behind the crankshaft, coating the points and removing their ability to provide a spark – not a problem encountered with the XS650’s cam mounted points. The alloy exhaust manifold would cause the head to overheat, and in some cases, crack.

Yamaha persevered. They redesigned the crankcases, fitted eccentric adjustable shafts to the balancer mechanism, and provided a deeper oil sump with anti-froth baffles. This, combined with a factory-installed oil cooler, removed the frothing problem and they doubled up the oil seals to keep the lubricant away from the points.

When Yamaha realised that the TX still wasn’t selling because of its reputation, they promptly shipped out new, updated engines to dealerships with bikes languishing unsold. Australian dealers were required to smash up the old engines with sledgehammers and scrap them to avoid import duty.

In 1974 they released an upgraded TX750A, with all those modifications made in the factory. Unfortunately, the reputation for fragility persevered, if unfairly. It remained a sales dud and after two years they dropped the TX. In Europe rumour has it that, in the end, Yamaha simply dumped the unsold TX750s in landfill.

The by-now tough and venerable XS650 returned to its place at the top of Yamaha’s tree until 1977 when, once more resisting their rivals drive to DOHC fours, they came up with the XS750 triple, a motorcycle with its own issues.

Today, the TX750 has a small but dedicated following, particularly in Germany, where members have been busy adding the upgrades to keep the TX going.

Riding a rarity: The TX750 on the road

The TX had just 9000 miles on the clock, and apart from a rusty silencer, some streaks on the chromed alloy casings and a dent in a side panel courtesy of a cack-handed Baltimore docks customs agent, it was in pretty good condition.

It was cold and damp on the roads. I thumbed the button and it rustled into life. Hang on though – this is a twin, so where’s all the vibration? This thing was as smooth as a big four. Smoother, even.

The handling felt a bit squishy, but from memory that’s the way 1970s Japanese motorcycles were. I felt it could do with some new fork springs, perhaps, and some thicker oil. After 40 or more years in a shed with all its springs under tension, you would expect a little bounciness. But that engine was a gem. It really did feel like a Honda four.

It accelerated hard too, when required, with none of that fraction of a second’s delay you get when an old four starts to spin. The riding position was near perfect. It’s definitely in the touring class than an out-and-out sportster – more like a modern Enfield interceptor than a 1970s Commando. Soft and comfy as a pair of old slippers, yet capable of picking up the pace when asked to.

This particular machine is one of the first batch and didn’t have the extended sump and eccentric balance shaft chain adjuster of the TX750A, so that would be worth hunting down.

There’s no oil cooler either, but a universal one wouldn’t be too hard to fit. A pair of pattern pipes and decent pair of Hagons on the back would be a real benefit. Maybe some sticky modern tyres too and some modern brake pads.

Surely you could improve that front disc with some braided hose, or search out the extra disc from a European model. Add some fresh modern oil, with a conversion from a German TX750 specialist to accept a BMW R65 oil filter, and…and…

You see, this unregarded, legendarily troublesome motorcycle has that kind of effect. Sure, there are going to be problems, you know that. Parts are going to be a challenge, for a start. But you can make all the calculations to find ways round them.

You’ll never see another, and the sheer joy of recovering something from its place in history will likely outweigh the negatives. It’s not worn out, after all, and is good for a few miles yet. Fancy one? This example is listed at somersetclassicmotorcycles.co.uk for £3,995.