ARCHIVE ALERT! This article originally appeared around two decades ago. Some things never change – RealClassic’s editor Frank Westworth is still a committed AMC Anorak – but don’t be surprised if some of the people and specialists he mentions are doing other things these days…

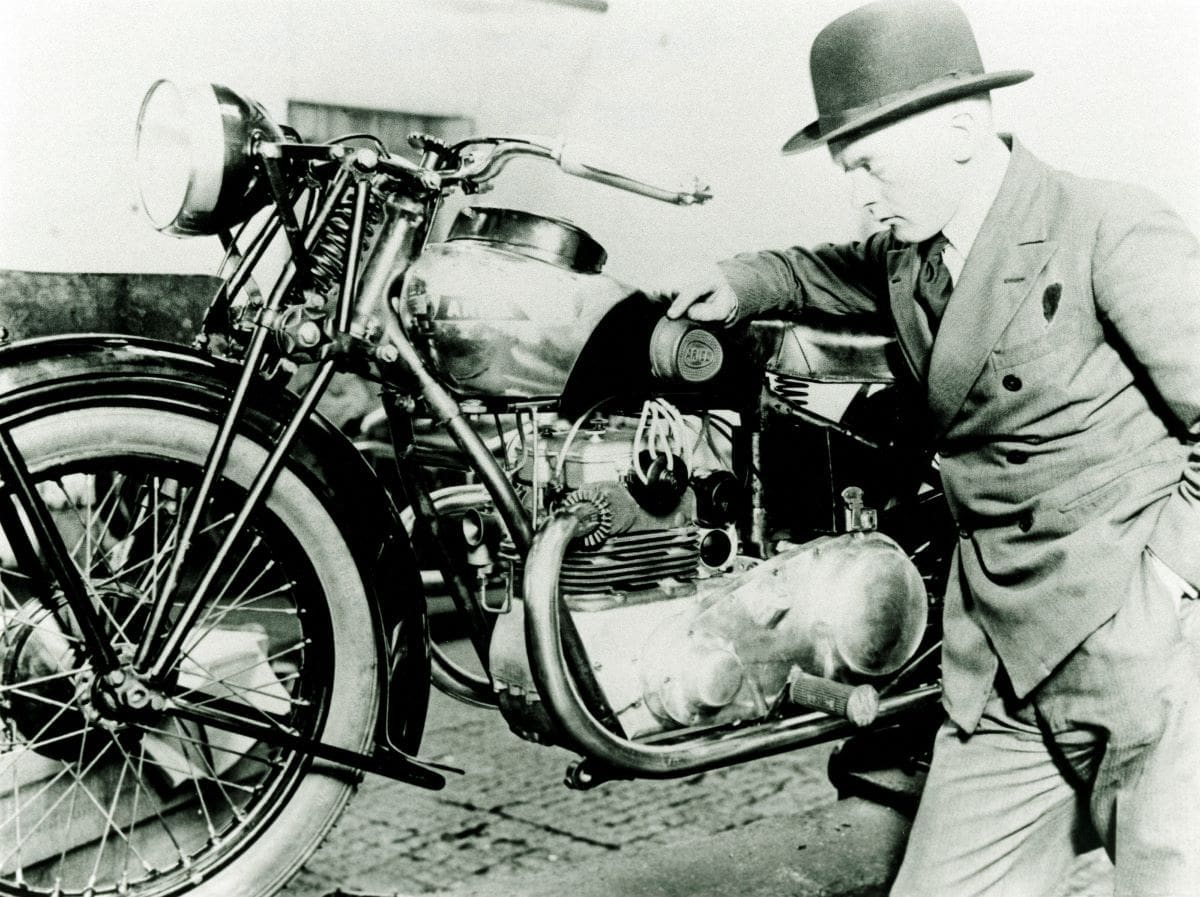

How do some folk get to be famous? Why do people rate Triumph and Norton engines so highly? Frank Westworth champions the AJS & Matchless underdog…

Let’s start with a simple test. Who was Phil Walker?

I’ll give you a clue; Phil Walker was not Edward Turner, nor was he Herbert Hopwood. He was, however, AMC’s equivalent; he designed the post-war AMC engines, like the twin and the lightweight single. So, why didn’t you know who he was? Why did some designers become famous and famously wealthy, while others languished in the outer darkness, even though their engines were arguably more advanced?

Don’t look here for an answer; I haven’t a clue. However, it’s a subject which has extended my curiosity for many years. An embarrassing number of years, in fact, ever since my lightness was darkened by the discovery that Erling Poppe, designer of one of the most imaginative Brit twins (the larger Sunbeam one, in case you were wondering), had been cast into the outer darkness by BSA, Sunbeam’s owners, after developing the S7 and S8; plainly a stroke of genius.

I should admit here that I am a fan of Phil Walker’s excellent twin engine; the one he designed for use in glorious AJS and Matchless machines. I always have been, ever since I rode my first, a 650, in 1971. It was great. When I stripped it down in 1972, I was even more impressed. What a device! What thought had gone into its design! What dullards and dolts its critics plainly were! Why, after gazing upon the wonder which is the AMC twin design, would anyone sing the praises of Edward Turner, the man who foisted off external and inevitably leaky pushrod tubes upon the masses? Or of Bert Hopwood, whose bizarre Dominator twin cylinder head has been a source of wonder to me for over thirty years? Mind you, Hopwood also produced the lightweight Norton twin, using some sound AMC design practice, so maybe there would have been hope for him if motorbicyclists in their millions had bought them at the expense of their weedy BSA and Triumph equivalents. However, history proves that they didn’t, so maybe Sixties riders really did deserve Hondas…

Consider Mr Walker’s twin, and compare it to Mr Turner’s. Only one of these designs supports its crankshaft properly; with a main bearing at each end, and one in the middle to stop the thing flailing about like a baggy elastic band. Both engines employ a separate camshaft for inlet and exhaust valves, unlike Mr Hopwood’s chain-infested Dominator, and both employ pushrods to twitch their valves into operation, but Mr Turner’s primitive device houses these pushrods in a pair of cheap tin tubes, which, quite apart from their noted propensity for lubrication leakage, obstruct the airflow to the hottest part of the engine; the chunk of metal between the cylinders. Count how many times Triumph had to add extra fasteners to hold down their heads (a clue; the Triumph twin started out with eight studs and ended up with ten), as opposed to the noble AMC engine (a clue; it started out with eight studs and ended up with … eight). And the AMC head studs also hold the barrels in place; none of those silly flanges and their unsightly external nuts here!

Before you say anything; any rumoured tendency of the AMC twin to blow head gaskets is plainly the result of poor pattern gaskets. So there.

Mind you, if you want to view design insanity at its unlovely best, take a look at how the top end is held down on Mr Hopwood’s Dominator twin. Take a close look; there are fasteners everywhere; nuts run up into the head, down towards the crankcase; they hide away beneath the exhaust ports and under the carb. It’s a nightmare.

Consider now how oil gets taken to lubricate the valves. Mr Turner? Unsightly and crack-prone external pipes. Mr Hopwood? The same. Mr Walker? The oil gets pumped up through drillways in the barrels themselves, as you’d hope. And if any oil leaks out of the fine AMC engine, why, it’s those rubbish pattern gaskets again!

Meanwhile, you can gaze in shock and awe at the incredible casting complexity of the Hopwood twin’s cylinder head. If I’m ever feeling low, I can go gaze at the engine in my Matchless G15CS. It always cheers me up. That casting alone must have cost more than a Tiger Cub. A complete Tiger Cub…

Then, confirm your sudden cheerfulness by looking at Mr Turner’s head (his cylinder head, not the meaty thing atop his shoulders). Notice that he plainly had shares in a company making studs and nuts, because there are loads of them, scattered hither and yon, attempting to stop the rocker box / head joints from leaking. And why would they leak? Because the pushrods push at rockers which are in the rocker boxes, at the same time attempting to unseat the boxes themselves. What a weedy design. In the noble and indeed handsome AMC Walker engine, the rockers are supported in pillars cast into the heads themselves; the covers are exactly that, covers. Unstressed, like most AMC riders.

And while we’re looking at the top end of the engine, consider the simple elegance of the separate cylinders and heads. Sylvan breezes are free to drift, unobstructed, between them, cooling the warmth of combustion as they pass. It’s almost Spring-like down there, unlike the massive, blocked, torturous airways in both Mr Hopwood’s and Mr Turner’s efforts, where cooling air is deflected by pushrod tunnels…

Now let us contemplate the oil pump; the core of every manly 4-stroke engine – and of many feeble strokers, too, of course. Look at Mr Turner’s bizarre plunger effort, where the drive is taken from a rotating camwheel, converted into reciprocation by a silly sliding block so that a pair of plungers can wear themselves out bopping up and down, attempting to deliver oil at any sort of pressure to the internals. No wonder Triumph twins rattle.

Moving over to Mr Hopwood’s engine, we find a sensible gear pump. Hurrah. But the drive to that is by a skew gear (very inefficient) and the feed from the pump goes, not straight into the engine but into the timing cover, where a tiny, wear-prone and occasionally unavailable tuppeny washer controls all the pressure to the engine’s vitals. No wonder Norton twins rattle.

Meanwhile, over in AMC-land, Mr Walker’s sublime design involves a neat pair of simple gear pumps, twirled into silent operation by each camshaft, and delivering soothing lube straight to where it’s needed the most. Wonderful. No wonder Norton and Triumph twins are so feeble. No wonder the AMC design outlasted them both. No wonder Triumph and Norton twins never won any races, while the AMC machines conquered the world!

OK, OK. I know. That last bit was just fantasy. There just ain’t no justice…