This beautiful 650cc Bonneville from what was arguably the pre-unit T120’s top year, does not disappoint.

What goes around, as they say, comes around. Back in the day (the early 1960s) Barry Winter, while already a committed Gold Star owner, had succumbed to the allure of the recently arrived T120 Bonneville, which at this peak of the rocker era, ruled the streets. He had ordered a brand-new 1961 Bonnie from his local Triumph dealer, Jim Pink at Wallingford, Oxfordshire.

But in 1960 the UK market for two-wheelers, for a variety of reasons, had fallen off a cliff, by 1962 down no less than 50% from its 1959 peak. Triumph concentrated on sales in North America, where they were already well established. America had been the target in any case for the T120, and a major influence on its development and style. Thus in 1961 months had gone by, with Barry being told that “They’re all going to the States.” So he cancelled his order.

Fast-forward 55 years to 2016 and Barry finally got his 1961 Bonnie, which had been one of the many, as explained, that had gone to America, and now been reimported. So – what goes around, comes around…

Why so special?

1961 was a model year when everything seemed to come good for Triumph’s twin carb T120 Bonneville. The original 1959 ‘Tangerine Dream’ Bonnie, with its colour scheme unacceptable in the States, and its traditional styling (headlamp nacelle, generous mudguards, front numberplate with chrome surround etc) had been radically revised for 1960, with a separate, jutting chromed headlamp permitting that rockers’ must-have, an optional (for the UK) rev counter (standard for US models), with a revised timing cover to take its drive.

Gaitered forks with internal revisions and a steeper, 67 degree steering head angle, shortening the wheelbase, carried a blade front mudguard, matched by an unvalanced one at the rear. The impression now was of lithe, purposeful lightness and it did not lie; at 390lbs the T120 was some 30lbs lighter than its BSA rival the A10 Super Rocket. The 1960 Azure Blue and Grey colour scheme, with blue the lower colour, improved on the former eccentric/effete tangerine/pearl grey, but wasn’t quite there yet.

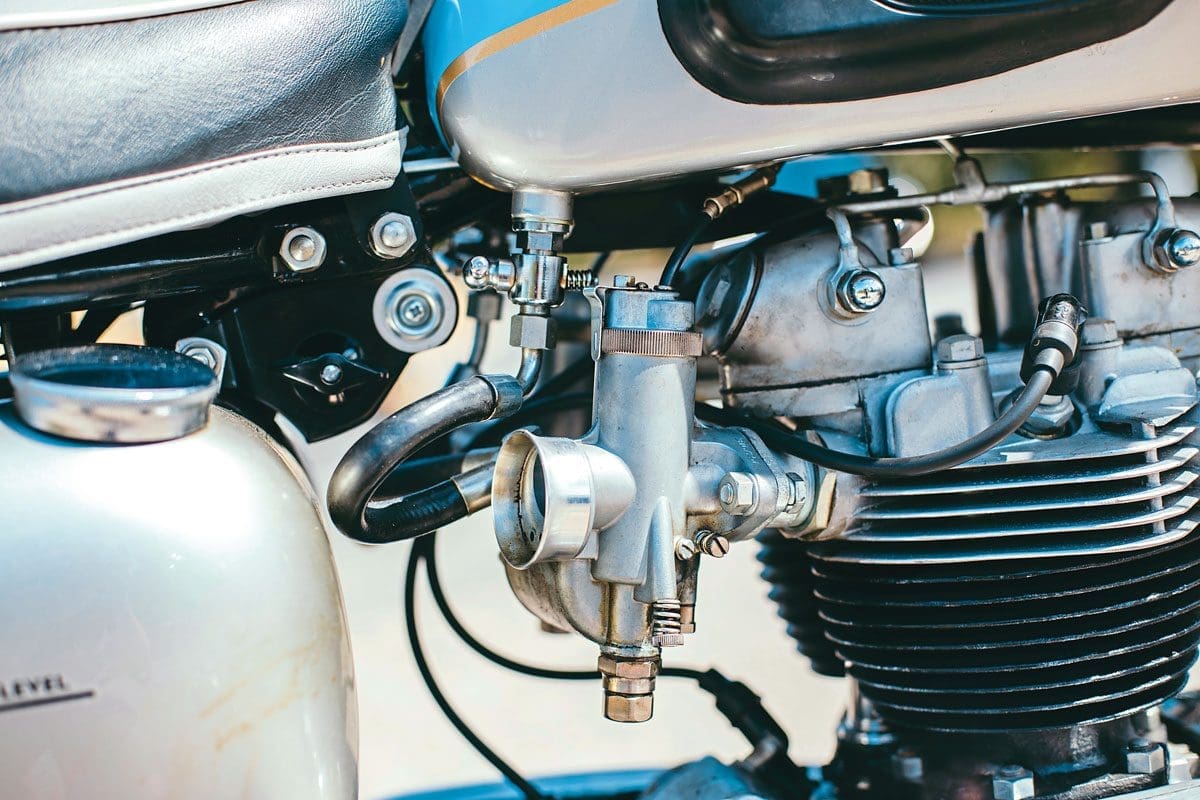

The previous troublesome twin carb set-up with its remote float chamber, which had been prone to fuel surge causing high-speed misfiring, and fussy running at low revs, was abandoned in favour of a pair of separately mounted Amal Monoblocs, something which some riders had already done for themselves. Overall, 52mpg was returned, pretty good for such a high performance machine.

More substantially, the ‘Triumphs don’t handle’ perception was addressed with a new duplex downtube frame. This had included an all-new rear frame now attached at the bottom via a substantial lug at the base of the seat tube, in a first attempt to counter the ‘Instant Whip’ effect of Triumph’s notoriously unbraced swinging-arm.

To go with the frame there was a new three gallon petrol tank, with three-point, rubber-mounted fixing, held down by a Norton-style rubber-lined chromed tank strap, which would prove prone to fracturing. Unfortunately the 1960 tank, being fixed at the front directly to the frame’s downtubes, may have contributed to some instances, mainly in US competition, of the downtubes breaking immediately below the steering head lug.

In December 1960, Edward Turner at the Big Bear Run witnessed a tragic example of this, where the rider was killed. Following an immediate test programme at MIRA to identify the problem’s cause, from engine/frame no D1563, the frame was revised with an extra, lower, tank rail, which could be retro-fitted to existing 1960 frames; and the petrol tank’s nose was strengthened for 1961.

This effectively cured the breakage problem, and for 1961 the revised frame provided improved handling, though some felt that the extra rail had increased vibration, not for the rider, but for components like the petrol tank retaining strip, which that year became stainless steel. The oil tank, and mid-year, the battery box fixings, became rubber-mounted.

The gearbox received improvements including Torrington roller bearings for the layshaft. With US preferences and competition in mind, the rear tyre became a wider 4.00×18, which combined with the 3.25×19 front, contributed subtly to the T120’s taut, crouched looks, like a coiled spring. A folding kick-start was standard, and the gearing, which had been lowered for 1960 via a 22 tooth engine sprocket and a 43 tooth rear sprocket, now dropped a little lower still, with a 21 tooth engine sprocket.

This related to young riders’ different benchmark for speed on either side of the Atlantic. Rockers would focus on top speed (108mph in the case of the 46bhp Bonnie as sold), while the Yanks, intent on the traffic-light Derby, first checked the standing ¼ figure (14.5 seconds for a 1962 T120, with a terminal speed of 85mph.) For 1961, mainly with off-road in mind, the steering head angle became two degrees less steep at 65 degrees, and this seemed to suit all parties, because riders everywhere loved the 1961 Bonnie.

If one impression dominated, it was the “explosive acceleration,” as Motor Cycling put it, in combination with such flexibility that “in London, it was one of the most pleasant machines we have ever used,” with a light, strong clutch, power available from anywhere in the rev band, and excellent brakes. The latter had been revised front and rear, with the friction strips resited at the trailing end of the shoes, which were made fully floating.

The new Sky Blue and Silver colour scheme added to the look of lightness. If one element let the package down, it was the secondary electrics. For while ignition was still by reliable, self-contained magneto (the Lucas competition K2FC was standard for US export models), 1960 had seen the dynamo replaced by a Lucas RM15 alternator behind a revised chaincase, and as Brooke and Gaylin recorded in “Triumph In America”, one dealer called the result “beyond bad”, due primarily to inadequate voltage control, with poor wiring harnesses, the quickly detachable headlamp which sometimes did so spontaneously, split batteries and flimsy dip-switches also contributing.

Today all these problems can be discreetly rectified with updates, and the 1961 Bonnie is about as good as the pre-unit 650s got. The 1962 T120, while broadly similar, saw the looks a little diluted with a return to black oil tanks/battery boxes, and in the engine, with higher balance factors, a wider, heavier flywheel, which while providing more scrambler-like grunt, meant that throttle response became a little slower. Then came the unit engine, another story. But few dispute that the pre-unit T120s and the 1961 in particular, provided a fundamentally sweeter ride.

Winter is coming

Barry Winter realised his dream in 2016, buying the reimported T120 from a specialist, an individual who rebuilds Triumphs on a part-time basis.

Possibly in his eagerness to secure that year and model, Barry took delivery although the restorer told him that the machine still needed some adjustments. He paid top dollar for the restored T120, way north of £8000, but these are sought-after models, relatively scarce (far fewer were built than the later unit Bonnevilles), and five figure prices are now being asked.

The restoration features a few minor lapses from strict originality. According to the late Hughie Hancox, the carburettors’ petrol pipes should be pre-formed transparent plastic; the tank’s short, front colour-dividing chrome strips are missing; and John Nelson in “Bonnie”, backed up with period factory photos, wrote that the two-tone dualseat fitted was not introduced until 1962, the 1961’s seat being black with white piping.

However this is not the first 1961 I’ve seen equipped with the grey top and lower trim strip seat, so maybe there was some overlap.

On delivery the bike had covered just 70 shakedown miles, and Barry would sometimes wonder how, as tickover was way off, with revs soaring alarmingly when the bike came to a halt at junctions. So Barry, with his other machines to enjoy, initially didn’t ride it very much, and a year passed before he began to sort it out.

“I played with the carburettors’ pilot jets and needles, and replaced the springs on the advance/retard unit, which cured the worst of it. It can still stall at the lights, but tickle it and it restarts easily.”

I was only to stall once, early on, and given a tickle, this T120 with its 8.5:1 compression is certainly a first kick start and restart machine.

“I’ve now done 1300 miles on it,” Barry continued, “I took it to the Isle of Man for the Southern 100 when it was running in – it had been rebuilt with new pistons and a rebore – but it went well, I saw 75 across the Mountain. With my Goldie you need to learn its quirks; the Triumph is easier to ride, more immediately responsive, and a lot of fun – and this is my first ever twin carb bike! It handles reasonably well. I haven’t had it on the track yet. I’m a heavy bloke, and it’s bottomed out on the rear springs a couple of times.” For 1962 the Girling units’ spring rate had been changed from an already firm 100lb/in, to an even stiffer 145lb/in. Maybe that’s what Barry should go for.

Speed king

What the 1961 T120 was all about was not its lightness, improved handling, ease of starting and the general achievement of a sports bike that was easy to live with – but its stunning acceleration.

The bare figures, 0-60mph in 6.4 seconds, do not begin to convey the raw excitement of the Bonnie’s urge. Fruit of precise valve timing, often achieved with the help of the optional three-keyway camshaft pinions, and the camshaft mix of the exhaust’s E3325 and the inlet’s legendary E3134, the latter based on the American-developed ‘Q’ cam, this was truly twist and go.

It spoke to the element, present to a greater or lesser degree in anyone who takes to the road on two wheels, that wants to go faster, faster than anything else, but also just faster, NOW! The need for speed.

I started and restarted the Bonneville easily, relished the mighty sound from the standard short silencers as I rode off, found that the uptilted UK bars did not dig painfully into my palms and provided a good forward-crouched riding position. And then, quite soon, twisted the throttle.

I was used to the relative liveliness of my single carb unit TR65, but this was something else – raw rush, such a responsive engine! Whey-hey!

It was impossible for spirits not to soar as the Triumph powered forward, as a motorbike should, somehow, as you dream it will. At the first twist of the throttle. From almost any revs, in any gear, again and again. And the four gears with their chunky change were well chosen and with such a good spread, that in the country roads, while far from holding back, and aided by the wieldy handling, I didn’t get out of third until near my destination.

They say that junkies with every new fix are actually fruitlessly chasing the unexpected, overwhelming sensations of their very first high. The rest of the test was a bit like that. Cornering for the camera confirmed dependable bend-swinging in the mid-range, and negligible troublesome vibration at those speeds. The rear brake worked better than the front, and together they were effective. Pulling in, neutral was almost always easy to find.

ff on my own again, with the tight engine at the far end of its running-in process, I couldn’t really explore the only other true question, what Motor Cycling had honestly noted, that “on really fast corners the machine was not completely steady.”

I took it up to 75 on a long straight and then through some gentle bends and felt, as they had, that the back end didn’t feel completely tight. But I would rarely ride a classic much faster than that, and the many plus points of the 1961 T120 thoroughly compensated for the fact that its frame was not a Featherbed, and not yet, as the unit 650’s would be, strengthened by Doug Hele.

But meanwhile I had definitely found out what all the fuss was about with these twins. Barry is a lucky man.