I still quite haven’t figured out either why BMW built the R45/65 series, nor why they failed to develop it further. For my money, the design showed so much promise: smaller, neater, sweeter than the other aircooled boxers (airheads, they call ‘em now, to differentiate them from the current ‘oilheads’), but that promise was never fulfilled.

You see, back in the Seventies all boxers were the same. They had the same frame, the same gearbox and the same stroke. An R80 was just a bored-out R75, itself a bored-out R60. The R100s were bored-out R90s, which were bored-out R80s.

This meant that it was (and still is) relatively easy to mix and match components and tweak models. Hell, by the late Seventies all the frames were being built with fairing mounts, so you could add an S or even RS fairing onto any naked BMW. Heads differed slightly – the 90S and 100S/RS got big valves, for instance – and final drive ratios differed but these were truly modular bikes.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

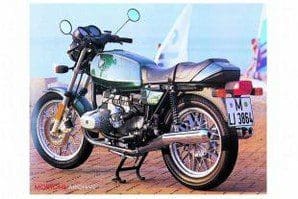

But the R45 and R65 were different. They had a shorter stroke engine and a completely different frame. Gone also were the familiar BMW twin clocks, to be replaced by a neat console which they shared with the R80ST. Sleeker styling made them look leaner and slimmer.

The R45 was soon dismissed as a slug. It was a sleeved-down R65, endowed with a single front disc instead of the 65’s twin discs, and was only really built for the German market where it fell into a convenient (low) power category, a bit like our 33hp post-learner bikes today. Our version developed a mere 35 bhp: the Germans got a 27 bhp version poor souls.

But the R65 had promise. It was effectively as fast as the R80 but it just lacked a vital amount of oomph. In 1981 it got it. In common with all the then BMW flat twins, BMW went on a weight-saving exercise.

But the R65 had promise. It was effectively as fast as the R80 but it just lacked a vital amount of oomph. In 1981 it got it. In common with all the then BMW flat twins, BMW went on a weight-saving exercise.

They junked the old heavy flywheel in favour of a lighter unit and other pruning lopped an amazing 20kg off the weight. Better still, a bit of attention to the air filter and exhaust raised peak power from 45 bhp to 50. It transformed the bike.

The other important mod (and again, this was applied to all BMWs) was the junking of BMW’s unimpressive ATE swinging brake calipers in favour of an all-Italian Brembo opposed-piston system. Bingo: lighter, faster, better-braked.

People suddenly discovered that the R65 completely out-handled all other BMWs with the possible exception of the R80ST. Its narrower engine (shorter stroke, remember) and different frame meant that it could be leaned over further, for longer. It still retained all the BMW virtues of mechanical simplicity, ease of maintenance, comfort and reliability.

It still had a petrol tank that (although looking at it, this was hard to believe) held nearly five gallons (22 litres) giving it a 200-odd mile range. So why didn’t it sell?

Possibly because it was seen as an entry-level naked bike. By the early Eighties people were buying BMW RSs and RTs like there was no tomorrow. Who wanted a little 650 that barely topped 110 mph? Especially one that cost about £2300 at a time when a Honda CB650 was under £1500 and a CX500, which had barely less performance and comfort and also boasted shaft drive, was little more than a grand.

In late 1981 BMW unveiled the R65LS and people got even more confused. This boasted a Katana-esque droop-snoot fairing that was claimed to reduce front wheel lift by a third. (Was front wheel lift ever a problem?) It got redesigned wheels, a slightly bigger rear drum brake, a restyled seat and front mudguard and, er, that was it.

The tank looked sleeker but it was in fact the same unit – clever application of two-tone paint make it look slimmer. It was also, for fans of trivia, the first bike to sport BMW’s new optional heated handlebar grips. Anyway, you could ride it slightly faster than the stock R65 because the fairing reduced the windblast on your chest but mechanically it was no different. It just looked flasher.

So what were they like to ride? Utterly delightful. So smooth, so sweet. There was an annoying vibration patch at about 70-75 mph (4500-5000 rpm) but that was easily driven through and anyway, it got less obtrusive as the miles piled on.

It handled, it really, really handled. On left-handers you could just get the sidestand down but the old BMW bugbear of grinding cylinder heads was absent.

Fuel economy was pretty good, if bemusing. I had one on test for three weeks in 1982 and I remember that I hammered it everywhere at 80-90 mph and it returned 45 mpg, which I thought was pretty good. For the sake of interest I rode it for a tankful at 70-75 mph, and it still did 45 mpg. Bizarre.

The R65 died when the monolever boxers made their appearance in the mid-1980s. Strangely, a couple of years later there was again an R65 in BMW’s line-up but this was not the same bike. It was merely the sleeved-down R80 in exactly the same chassis – and it was a slug.

BMW had obviously decided that there was no point in having two sets of tooling to produce two outwardly similar boxers and they killed the most delightful boxer engine they ever made.

What goes wrong

What goes wrong

Very little, as you might expect. A batch of early R65s had weak gear lever return springs. A mate of mine had one and it went ping as he was on his way to the Bol d’Or at Paul Ricard. He made it to the South of France and back two-up, permanently stuck in fourth, and had to slip the clutch to 35 mph.

Amazingly, it made it home, although the clutch plate looked like it had been toasted. This was fixed under warranty. It was a gearbox-out job and they replaced the clutch too!

The electronic rev counter can malfunction. This is usually due to damp and corrosion affecting the contacts: a problem that afflicts other old BMWs. The wheels were made of a very soft kind of alloy. Not long after, BMW had a well-publicised alloy wheel recall as they were bending far too easily in moderate impacts like pot-holes.

Early LS models had matt black painted exhausts and the paint fell off in the first rainstorm, leaving them looking like something off a neglected Guzzi Le Mans. BMW swiftly changed them for black chrome pipes but even these looked manky quite quickly. Later R65s got chrome exhausts.

A few suffered from gearbox whines but again, that was a problem that other BMWs suffered as well. It was usually a manufacturing rather than design fault.

What to look for

First off, forget the R45 unless you just want basic wheels and are skint. The 65 is the one to have. If you are unfamiliar with old boxers, try to find someone who understands them.

Check the points listed above. Especially check the exhausts, as these are never cheap to replace. The good news is that all sorts of patterns are available, including stainless steel.

Have a look at the finned manifold clamps – these must be undone with a special tool and invariably people batter them with a hammer and drift and snap the fins off. If they aren’t reassembled with loads of copper grease, they seize, the threads get damaged and it costs a lot to have them repaired. Treat any boxer with damaged manifold clamps with the greatest suspicion.

Have a look at the finned manifold clamps – these must be undone with a special tool and invariably people batter them with a hammer and drift and snap the fins off. If they aren’t reassembled with loads of copper grease, they seize, the threads get damaged and it costs a lot to have them repaired. Treat any boxer with damaged manifold clamps with the greatest suspicion.

Rust isn’t a real problem. There’s not much chrome apart from the exhausts. BMW’s good finish means that frame and bodywork paint resists the passage of time better than that of many other manufacturers.

Ideally, you want a bike that’s got a pannier set fitted. Most will at least have the frames but at this age one or both of the panniers may have been damaged, which means hunting round autojumbles for replacements. If humanly possible, get a Brembo-braked model.

Beware any bikes with damaged instruments – that clock set was only fitted the to the R45/65 and the R80ST and used instruments are far harder to find than they are for the other boxers.

Don’t pay any more for an LS. Some dealers bolted RS and RT fairings onto the R65 (and some really optimistic dealers even kitted out the R45 the same way). I think, to be honest, it’s just too small and low-powered to carry that much fibreglass, but your mileage may vary, as the Yanks say.