Brooklands Track, Weybridge, Surrey. The first motor racing arena in the world — it was conceived and brought to execution by one man, wealthy land owner, Hugh Locke-King, with the constant support of his wife Dame Ethel. He donated over 30 acres of his estate, and spent more than £150,000 of his own money — call it eight million today!

The track was designed by the celebrated Colonel Capel Holden of the Royal Engineers, and was probably the first significant piece of civil engineering in the world to be carried out in concrete. It was, at all places, 100 feet wide, and the two bankings rose 30 feet into the air. It was Col Holden’s intention that a car, of sufficient power, should be able to lap ‘hands off at 120mph. At 2¾ miles to the lap, the whole track was visible from any one point.

Up to 2,000 workmen, craftsmen and labourers worked for almost exactly nine months from felling the first tree until the track’s completion. They had the benefit of steam drags and shovels, and even their own light gauge steam railway! Between them they shifted 350,000 cubic feet of soil and laid 200,000 tons of concrete. Spectators, entrants and clubmen were well provided for and there was a large concrete paddock.

Racing began early in July 1907 and ended in 1939 with the outbreak of Hitler’s war. Curiously, racing was not entirely eliminated during the Great War of 1914-18, but was diverted into ‘Khaki Meetings’.

Racing began early in July 1907 and ended in 1939 with the outbreak of Hitler’s war. Curiously, racing was not entirely eliminated during the Great War of 1914-18, but was diverted into ‘Khaki Meetings’.

Without a doubt, hand in hand with the Isle of Man TT, Brooklands Track was an enormous force for the good of the British Motor Cycle, which under those two wisely administered disciplines became, simply the most successful in the world.

Motorcycles did not race at Brooklands until early 1908, and their inception was tame enough – a one-lap match event between W G McMinnies on a 3½hp single-cylinder Triumph and 0 W Bickford with a 5hp V-twin Vindec both of them TT (stripped) models. McMinnies won comfortably and later recorded an average two-way speed of 58.8 mph over the flying half mile.

Response was guarded, even The Motor Cycle admitting that this race (put on by the Brooklands Automobile Racing Club in the course of a car meeting) was hardly spectacular. However, the BARC offered an open race at its Easter Monday meeting and secured a remarkable entry of 24. A scratch race of two laps, the event was a benefit for W E Cook on a 7.9hp (1000cc) NLG Peugeot V-twin, followed by a similarly engined Leader ridden by Eddie Kickham. C R Collier was third on a 6hp Matchless twin and the first 500cc finisher was McMinnies (fourth) on his Triumph single.

Said The Motor Cycle “Big engines do not automatically win but other things being equal, it is only natural that they should do so nine times out of ten.” It seemed only common sense to run future races as handicaps.

The Motor Cycle for April 29, 1908, under the heading, “Handicapping at Brooklands”, added: “Encouraged by the large number of entries received for the first open motor cycle race at Brooklands, the BARC has decided to hold a motor cycle handicap plate of twenty-five sovereigns at the forthcoming meeting on May 9th. The conditions are not yet issued, but we understand that the engine size limit has been increased from 80mm by 98mm for twin cylinder to 85mm by 95mm each cylinder.

“With regard to the handicap, we should like to offer a suggestion which was recently made in our pages, that in order to encourage slower machines the handicap should be framed upon the times made in a previous scratch race. The idea was first suggested in The Autocar, and was tried at Brooklands on April 4th, and resulted in some very close finishes. Owing to the length of the race (twenty-two miles), the proceedings were somewhat tedious in running off the scratch race, but in the case of the motor cycle handicap, if confined to five and a half miles, there would not be the slightest difficulty. The handicap would be framed as follows — a scratch race would be run, everyone starting off the same mark, and times would be taken for each competitor.

“With regard to the handicap, we should like to offer a suggestion which was recently made in our pages, that in order to encourage slower machines the handicap should be framed upon the times made in a previous scratch race. The idea was first suggested in The Autocar, and was tried at Brooklands on April 4th, and resulted in some very close finishes. Owing to the length of the race (twenty-two miles), the proceedings were somewhat tedious in running off the scratch race, but in the case of the motor cycle handicap, if confined to five and a half miles, there would not be the slightest difficulty. The handicap would be framed as follows — a scratch race would be run, everyone starting off the same mark, and times would be taken for each competitor.

“To prevent ‘roping’, if a competitor improved upon his scratch time by more than an experimentally predetermined number of seconds, his fastest time would not count, and his time would be counted from the speed accomplished in the scratch race. As an example of the handicap, if in scratch race A made the fastest time, and B was 10s slower, B would receive 10s start from A; but if A only made the same time as in the scratch race, and B improved on his scratch time by 4 3/5s. This is allowing for a pre-determined 5s allowance between the times made in the two races.”

And so it was to be. Supervised by the implacable E V Ebblewhite (‘Ebby’) handicap racing became the order of the day, rescuing British racing from the ‘Monster’ approach that killed off the sport in France.

For the meeting of May 9, 1908, a remarkable field of 31 starters faced the flag. Winner of the two-lap handicap was H Shanks (2¾hp Chater Lea) with a start over the scratch mean of no less than 2m 24s! Even so, ‘less than a wheel’ separated the first three home — Shanks being followed by H G Partridge (6hp NSU with 45s start) and W H Bashall (V: Triumph with 40s start). Only four riders had to retire.

Handicapping

“Racing as such was not exactly exciting before 1914 if the truth be told,” said The Motor Cycle. “Furthermore, the handicapping makes it hard to follow the old race results, although it undoubtedly added interest to those spectators who had a ‘favourite’ — especially if they had a good bet on with one of the several bookies!” Speeds crept up quite slowly. By the time of Indian’s class sweep of the 1911 TT Charlie Collier and Jake De Rosier in their famous match races were lapping at around 8omph on their i000cc V-twins. Even so, one could not help feeling that, taking part was far more exciting than watching!

Of course, Brooklands was absolutely ideal for testing, tuning and record breaking and almost at once these activities came under the British Motor Cycle Racing Club (‘BEMSEE’) founded in 1909. By 1911, at least two manufacturers, Singer and Norton had their own establishments (and resident riders George Standley and Dan O’Donovan) at Brooklands. Very soon they were joined by others and depots for tyres, fuel, oil, machining, bodywork etc were set up. By 1914, the Paddock housed a quite extended and very active mini industrial estate.

So much activity must have made life for the local residents a rather noisy one, and of course this led to the introduction in 1924 — both for motor cycles and cars — of the Brooklands silencer, to specific dimensions, but soon to settle in appearance to the famous lozenge shape with its fish tail.

Competition bred competition and the fastest speed before the war rose to 93.48mph over the flying kilo — set by Stewart St George on a i000cc Indian. This was a very respectable speed for the time.

Competition bred competition and the fastest speed before the war rose to 93.48mph over the flying kilo — set by Stewart St George on a i000cc Indian. This was a very respectable speed for the time.

But not until 1921 was ‘oomph’ achieved over the flying kilo by D H Davidson on a Harley-Davidson, and it was 1923 before Bert Le Vack lapped at 100mph on his Zenith JAP V-twin. For that 100mph lap, made during the course of a race, BMCRC awarded Le Vack the first of 180 ‘Gold Stars’ (brass, actually). Of these, only one was in the 250cc class, won by M B Saunders on Willy Worters’ streamlined Excelsior JAP.

Twenty-five stars were awarded to riders of l000cc machines, 21 to riders of 750s. The greatest number was in the 500cc class with 100 stars and there were 29 in the 350cc class. Lady riders, Florence Blenkiron and Gertrude Shilling, won 500cc Gold Stars and Teresa Wallach one for the 350cc class.

Three intrepid pilots of sidecars won Gold Stars — Freddie Dixon, Ted Baragwanath and Noel Pope. Only Pope and Eric, Femihough won ‘Double’ Gold Stars for laps at over 120mph and the fastest lap evr on two wheels was Pope’s 124.51mph on his ‘blown’ Brough Superior. It might be though that to get a Gold Star all one had to do was open the throttle wide and hang on for dear life. Not so!

Certainly the ‘Golden Days’ were in the 1920s when bonus for races and records (not to speak of generous prize and starting money) was pressed upon the willing riders and sponsors by the accessory companies.

One of the most famous recipients, Excelsior exponent Willy Worters, claimed that making the rounds at the 1927 Show he collected guaranteed sponsorship of about £1,500 (say £30-40,000 in today’s terms) ‘without so much as having wheeled a bike out of the shed!’

Big twins

Bert Le Vack always favoured the big twins, of course, and was employed by JAP and later, New Hudson, for both of whom he designed engines — and won Gold Stars in the l000cc and 500cc classes. But Bert retired well before 1930 to go to work for MAG in Switzerland. Several other ‘tuners’ such as Doug Marchant (Blackburne’s man at Brooklands) and George Patchett also ‘went foreign’ during the Depression.

Rivals — and friends, but only off the track were Bert Denley and C W G (Bill) Lacey. Bert was first with a 5oocc Norton to put too miles into the hour — at Montlhery, near Paris — but he had held ‘the hour’ no less than five times at Brooklands. Bert, again retired after 1930 joining Captain George Eyston and his record-breaking car team.

At the time of his retirement, Bert still had his name on 43 world records!

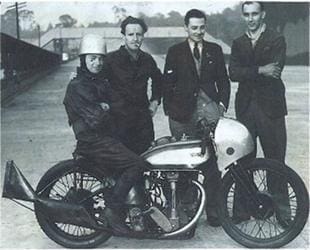

Bill Lacey could not match that, but he probably won more races during his career, which lasted somewhat longer than Bert’s. And Bill was the first to put ioo miles into the hour at Brooklands in 1928 — 103.3 miles in fact. His superbly prepared 500cc Grindlay Peerless — JAP was (and still is) an eye opener in its polished nickel finish. Nor did Bill abandon two wheelers in later years. In between servicing Cosworth Grand Prix car engines, it was Bill who built and tuned the 500cc Manx Norton engine that Mike Hailwood used to win the Senior TT of 1961 the last ever such victory.

Bill Lacey could not match that, but he probably won more races during his career, which lasted somewhat longer than Bert’s. And Bill was the first to put ioo miles into the hour at Brooklands in 1928 — 103.3 miles in fact. His superbly prepared 500cc Grindlay Peerless — JAP was (and still is) an eye opener in its polished nickel finish. Nor did Bill abandon two wheelers in later years. In between servicing Cosworth Grand Prix car engines, it was Bill who built and tuned the 500cc Manx Norton engine that Mike Hailwood used to win the Senior TT of 1961 the last ever such victory.

Short of reciting their wins and records what can one say about riders such as Claude Temple, Oliver Baldwin, Vic Horsman and Chris Staniland, Les Archer? One can only acknowledge that they — and many, many more earned a place in history, most worthily.

For light, almost comic, relief there were the exploits of two, three, even four wheels by J J Hall, who in later years was to play such a part (writing in Graham Walker’s Motor Cycling) in the post-war arousal of interest in what we now regard as Vintage motor cycles.

Jim Hall looked for a profitable gap in the regular pattern of record breaking at Brooklands and found one. After all he reasoned, a record, to the average punter was a record no matter what the category. So, at minimal expense to himself, he built a series of ‘specials’ with engines of 5occ, 75cc, l000cc and 125cc (all of which were catered for but very rarely contested.) Because fuel and oil companies regarded these records with some disdain, Hall specialised in securing backing from the most unlikely sources such as makers of patent medicines, hair oil, and prophetically tobacco and cigarettes!

All these records — some of quite considerable distance — were held at speeds around Oomph. Death from boredom must have been a hazard, but nevertheless J J Hall actually made a living at Brooklands!

Of all the thousands of races ever run at the big track, one particular event stands head and shoulders above the rest as having been as thrilling as any in the history of motorcycle racing.

The occasion was the 1926 200-mile Scratch race, and the man who provided the excitement was that strange, tormented genius, Walter Handley, in the 350cc class.

Waiting for the flag, Walter’s mechanic Sammy Jones spotted an obvious hacksaw cut to the front tyre of Walter’s Rex Acme Blackburne. Walter’s wretched luck was part of folklore but this was plain sabotage.

Waiting for the flag, Walter’s mechanic Sammy Jones spotted an obvious hacksaw cut to the front tyre of Walter’s Rex Acme Blackburne. Walter’s wretched luck was part of folklore but this was plain sabotage.

In silent fury, he and Sammy rushed the bike back to the paddock and managed to replace the cut tyre. By the time Walter actually started, the race was seven laps into its distance almost one tenth completed!

With Bill Lacey on his rapid Grindley-Peerless way out in front, who would have given Handley a chance in a hundred of finishing in the first dozen? Well Sammy Jones would for one. “He was uncanny — super human”, said he. “If I could get a bike to do 90mph, Walter could wring out another couple of miles per hour under exactly the same conditions!”

Be that as it may, incredibly, by 40 laps Walter had pulled back the deficit (and in doing so had passed some of Brooklands’ fastest and best) to lie in third place!

In fact, he finished second to Bill Lacey, a mere two minutes and two seconds adrift! Lacey’s speed for the race was 81.2mph — Walter’s (remember that late start) 80.26mph. In the course of this epic ride, Walter Handley and his Rex Acme broke no fewer than seven world records!.

The 19030s saw drastic changes. Sales of motorcycles began to fall, and interest in racing - especially in record breaking – fell off amongst the accessory firms. By the mid-30s, many concerns such as Shell, Esso, Mobil and Castro], who did have money to spare, decided that the TT provided better advertising.

Motorcycle racing at Brooklands finished on a low key with a BRMC meeting in August 1939.

And that was that, or so it seemed. When the war ended, the track wsa sold to Vickers Armstrong to develop as a large insustrial estate. Derelict and overgrown as the track has become, it was rescued from oblivion when the Brooklands Society was formed to preserve its memory. View original article