Asked to name BSA’s best-ever motorcycles, many enthusiasts would plump for the Gold Star or the Rocket Gold Star, while those who think that rear suspension is unnecessarily effete might opt for the Sloper (whose star-marked tuned engines incidentally led to the later models’ names). Some down to earth souls might name the Golden Flash or the Bantam, but I bet very few would even think about the unit-construction twins made from 1962 until BSA’s final extinction a decade later.

Why? Well probably because all the earlier models were significantly better than their direct competitors in at least some respects – faster, better looking, more reliable or whatever – while it was generally considered that the A50 and A65 were basically repackaged and less charismatic versions of their predecessors. And of course, during the 1960s the restriction of learners to quarter-litre machines meant many motorcyclists had developed a brand loyalty to one of the more sophisticated oriental marques before graduating to bigger bikes, so they had an inbuilt aversion to the sort of motorcycles that had satisfied a previous generation.

They had a point. Motorcycles like the A65L Lightning – made at the end of Small Heath’s productive life – bore the same relationship to a Japanese bike as a sundial does to a Rolex watch. But I said that the earlier BSAs were well regarded because they were better than the immediate competition, and the simple fact is the last BSA twins had virtually no direct challenger.

They had a point. Motorcycles like the A65L Lightning – made at the end of Small Heath’s productive life – bore the same relationship to a Japanese bike as a sundial does to a Rolex watch. But I said that the earlier BSAs were well regarded because they were better than the immediate competition, and the simple fact is the last BSA twins had virtually no direct challenger.

There was the Triumph Bonneville, of course, but that was so similarly priced and specified the choice between it and the Beeza really came down to brand loyalty, and there was the 750cc Norton Commando, which was clearly aimed at a quite different market niche, besides being significantly more expensive. So if you were one of the admittedly dwindling few who wanted a big traditional twin, and were determined to buy British, the A65 must have been quite an attractive proposition; and for the rather larger proportion of enthusiasts attracted to such machines today, I reckon it’s become something of a bargain. You can pick one up in decent running order for considerably less than you’d pay for a contemporary Triumph or Norton, and at a fraction of the cost of either a single or twin cylinder Goldie.

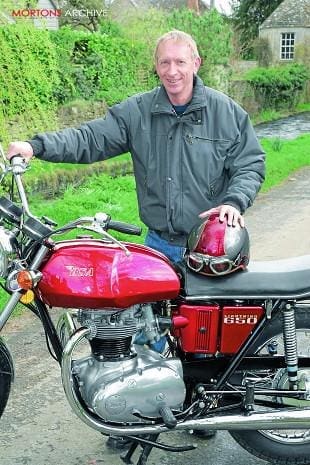

The test A65L – which was originally registered for use as part of a sidecar outfit – was first restored in 1982 (after being bought for £150!) but it was subsequently neglected for the best part of 20 years before Gloucestershire enthusiast Fred Dyer took it over. Fred was a BSA/Triumph fan before marriage and fatherhood intervened, and he then developed an interest in old cars until back problems made crawling under chassis an unattractive hobby. It also finished a career in the local sand and gravel quarry, and a few years ago he returned to bikes with the restoration of a BSA B25, his new job as a care worker on night shifts giving him plenty of time in the garage.

After its long hibernation Fred says that the A65L had become a ‘rust bucket’, but crucially it was all present and correct (even including the original tool roll!), and as it had still covered less than 20,000 miles it seemed well worth the asking price of £2000. Fred sensibly didn’t do too much work on it straightaway, but simply checked it over for safety before setting off to the Isle of Man with some mates. He had a superb time with no significant mechanical problems, and on his return decided to invest in a complete re-restoration.

After its long hibernation Fred says that the A65L had become a ‘rust bucket’, but crucially it was all present and correct (even including the original tool roll!), and as it had still covered less than 20,000 miles it seemed well worth the asking price of £2000. Fred sensibly didn’t do too much work on it straightaway, but simply checked it over for safety before setting off to the Isle of Man with some mates. He had a superb time with no significant mechanical problems, and on his return decided to invest in a complete re-restoration.

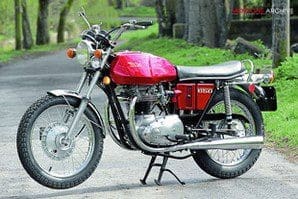

When stripped, the engine turned out to be in fair condition, and most of the original cycle parts were salvageable. The rear suspension units, for example, are the ones fitted at the factory, and even the chrome on the springs came back to life with a lot of elbow grease. The front rim had been changed from a Dunlop or Jones to a Radaelli – presumably during the first rebuild – and Fred had that re-chromed by nearby plating specialists S&T besides adding a matching rear hoop. S&T also re-plated the exhaust system – which seems to be original – and it looks superb. The plating was easily the most expensive part of the restoration, but there is really no way round that if you are aiming for an as-new or better appearance. The paintwork is definitely better than new as it was originally done in BSA’s curiously drab bronze (Fred has a more descriptive but unprintable name for it…) but after consultation with his local paint shop he decided to switch to the much more attractive Candy Red option.

The result of all this is a motorcycle that cost less than three and a half grand (see what I mean about these bikes being good value?) despite its absolutely stunning looks. And that leads me to backtrack slightly on the model’s history, because when the A65 and the almost identical half-litre A50 were launched in 1962, it seems BSA initially misjudged the importance of their appearance in a fairly dramatic way.

The result of all this is a motorcycle that cost less than three and a half grand (see what I mean about these bikes being good value?) despite its absolutely stunning looks. And that leads me to backtrack slightly on the model’s history, because when the A65 and the almost identical half-litre A50 were launched in 1962, it seems BSA initially misjudged the importance of their appearance in a fairly dramatic way.

The switch to unit construction was perhaps understandable as it did make the engine/gearbox look more modern and easier to keep clean, and it undoubtedly reduced both the motorcycle’s weight and its production costs. But the designers’ big mistake was that they ignored the mega-attention showered on the obsolescent Rocket Gold Star – while the Golden Flash on which it was based had virtually faded into obscurity – and failed to appreciate the importance of a big bike looking like a real man’s machine. As a result the new BSAs were given a smooth, cuddly, appearance that was as bland as that of their engines. Even worse, the simplified shape of their engines left a visual hole that some design genius partially filled with ungainly steel side panels so bulky they could impede your leg when kickstarting.

Things looked up slightly when the A65L Lightning was introduced in 1964, effectively replacing the short-lived Rocket, and based on the twin carburettor Lightning Rocket already available in the USA. Among other cosmetic changes – most notably extra chrome plating – the unpopular side panels were made somewhat neater, and were now moulded in glass fibre. More importantly – at least as far as street credibility was concerned – the engine’s high compression pistons and sports camshaft gave it nearly 50bhp, and the top speed easily exceeded the magic ton.

You wouldn’t want to do that very often, though, as testers reported vibration became serious when the motor hit 5000rpm at about 80mph, and at about that speed the front end of the bike started to weave! There were also electrical problems on early examples, where it was wise to avoid the extra cost option of a 12v system (provided by simply adding a second 6v battery in series) as inadequate voltage control led to boiled batteries if high engine speeds were maintained.

You wouldn’t want to do that very often, though, as testers reported vibration became serious when the motor hit 5000rpm at about 80mph, and at about that speed the front end of the bike started to weave! There were also electrical problems on early examples, where it was wise to avoid the extra cost option of a 12v system (provided by simply adding a second 6v battery in series) as inadequate voltage control led to boiled batteries if high engine speeds were maintained.

To its credit BSA steadily developed the big twins, even though some changes took a long time to filter through to production. It was 1970, for example, before the cylinder base was enlarged to permit a larger gasket area and stronger holding-down studs. At the same time, the pistons, oil pump and clutch were all improved and capacitor-aided ignition was fitted.

None of this makes much difference to a sensible classic motorcyclist today, as apart from legal considerations and improvements in battery management, it would be asking for trouble to expect a motor that’s several decades old to rev out to the max. So the tachometer that mirrors the Smith’s speedometer on Fred Dyer’s A65L is hardly essential, but it’s interesting to be able to see that his preferred cruising speed of 60-65mph is held at less that 3500rpm on a whiff of throttle.

The engine couldn’t be described as silky smooth, but the vibration is never obtrusive and Fred’s clearly got the two carburettors well tuned – a job made easier by the twin-cable twistgrip that replaced the junction box used on earlier twin carb BSAs – as the motor picks up smoothly besides being quite happy trundling along at 30mph in top. Riders used to modern machines would find the clutch rather heavy, but it’s typical of sportsters of the era, and it works well in conjunction with a light and precise gearchange that probably raised marque traditionalists’ eyebrows when they found that it was ‘one down and three up’ in the Triumph style.

In the mid-1960s the forks were given two-way damping for the first time, and the frame was modified to improve stability at high speed. But, at the end of 1971, BSA undid all the good work with the much criticised change to the oil-in-frame chassis developed by its Umberslade Hall development centre.

The area where the most significant changes were made during the Lightning’s nine year production span was to the forks and frame which were initially closely related to those used on the old A10. In the mid-1960s the forks were given two-way damping for the first time, and the frame was modified to improve stability at high speed. But, at the end of 1971, BSA undid all the good work with the much criticised change to the oil-in-frame chassis developed by its Umberslade Hall development centre. It was adopted on both BSA and Triumph twins despite the bitter rivalry between Small Heath and Meriden, and while there wasn’t anything particularly wrong with the frame other than an increase in seat height to 33 inches (even higher on the Triumph) which was detested by short-legged owners, it was no great improvement either. The promised increase in torsional stiffness and decrease in weight was simply not apparent to the rider, and there was a mixed reaction to the new transatlantic styling with high and wide handlebars which would have made continuous high-speed cruising impractical whatever power and handling were available.

But it must be admitted the new front fork introduced for both makes at the same time was a definite improvement. Developed from the one used on BSA’s motocrossers, it was obviously more than strong enough, besides having better damping and 6.5inches of movement. The ‘conical hub’ twin leading shoe brakes used on both makes from this time onwards were extremely effective, too, and equally importantly they looked really impressive with their large air scoops. The forks’ stylishly exposed stanchions were naturally subject to corrosion, especially when a bike had been laid up like Fred Dyer’s. He naturally had to go shopping for replacements, and was delighted to find his local dealer had a pair that had rested on the shelf for 30-plus years, and was even happier to only be asked for the £40 shown on the original price tag!

But it must be admitted the new front fork introduced for both makes at the same time was a definite improvement. Developed from the one used on BSA’s motocrossers, it was obviously more than strong enough, besides having better damping and 6.5inches of movement. The ‘conical hub’ twin leading shoe brakes used on both makes from this time onwards were extremely effective, too, and equally importantly they looked really impressive with their large air scoops. The forks’ stylishly exposed stanchions were naturally subject to corrosion, especially when a bike had been laid up like Fred Dyer’s. He naturally had to go shopping for replacements, and was delighted to find his local dealer had a pair that had rested on the shelf for 30-plus years, and was even happier to only be asked for the £40 shown on the original price tag!

This Lightning was one of the last made – sold in January 1973 after production had actually ceased – and it benefits from the final upgrades made by Small Heath before it imploded. In particular there were frame improvements instigated by industry legend Bert Hopwood, who had become a director after an illustrious career with most of the major factories, most notably Norton. He was aided by Doug Hele who had all but cured Triumph’s handling maladies during the mid-1960s, and subtle changes – including shorter rear suspension units – reduced the saddle height by two inches with no reduction in comfort and a noticeable improvement in handling.

The result is that, like most BSA twin tourers – whenever they were made – the Lightning is a very pleasant bike to ride, with suspension that’s soft enough to provide excellent comfort without compromising road holding. I’m not going to test the handling at the licence-threatening speeds that caused qualms with early models, but I suspect it would be quite acceptable and it is certainly spot-on at legal speeds when my enthusiasm is only curbed by the ease with which the sidestand grounds on left-hand bends.

Additionally – in my opinion at least – BSA finally got the styling absolutely right on these late models. No longer did the big twins look like overweight C15s, a proper headlamp shell replaced the cheapo rolled sheet nacelle, and the unpopular side panels were abandoned in favour of visibly sensible oil, battery and air filter boxes. These were complemented by a no-nonsense petrol tank that some thought slab sided, but which undoubtedly gave the bikes a clean, lean appearance. A compensating touch of West Coast frivolity was provided by the exposed forks and wide handlebars, plus mudguards that were too abbreviated to be much use, but, hey, we were into the 1970s, and motorcycles were already becoming a summer luxury rather than a year-round necessity.

Additionally – in my opinion at least – BSA finally got the styling absolutely right on these late models. No longer did the big twins look like overweight C15s, a proper headlamp shell replaced the cheapo rolled sheet nacelle, and the unpopular side panels were abandoned in favour of visibly sensible oil, battery and air filter boxes. These were complemented by a no-nonsense petrol tank that some thought slab sided, but which undoubtedly gave the bikes a clean, lean appearance. A compensating touch of West Coast frivolity was provided by the exposed forks and wide handlebars, plus mudguards that were too abbreviated to be much use, but, hey, we were into the 1970s, and motorcycles were already becoming a summer luxury rather than a year-round necessity.

Little has changed in the ensuing years, with classic bikes generally reserved for high days and holidays. Still a luxury perhaps, but at least the A65L is an attractive, usable and affordable one.