To put it kindly, BSA’s unit-construction singles didn’t exactly enjoy the best of reputations; and that was despite seeming initially to have everything in their favour. First in the range was the 1958 C15, and compared with its C12 predecessor – recognisably based on the pre-war C11 – it was significantly lighter, undeniably neater, and noticeably sprightlier. And what’s more, its engine was based on an already-established design.

Unfortunately, that was the cause of most of the subsequent troubles. BSA was allied to Triumph under the leadership of Edward Turner, and he had introduced Meriden’s Terrier/Tiger Cub singles some years earlier. Now Turner wasn’t the sort of man to relish spending money on re-development – especially when it implied criticism of his own ideas – so he naturally decided to power the C15 with an expanded version of the Cub engine, even though it had already shown some alarming weaknesses.

No doubt he blamed the ensuing problems on the owners, and both the Tiger Cub and the C15 were undoubtedly competent little machines when ridden within their limits. The trouble was that they were small, cheap and smart enough to appeal to novices who just didn’t realise where those limits lay. And who – other than Turner – could blame them? If a road test said that a C15 had a top speed of 75mph, it must have seemed reasonable to try to achieve that on every occasion.

No doubt he blamed the ensuing problems on the owners, and both the Tiger Cub and the C15 were undoubtedly competent little machines when ridden within their limits. The trouble was that they were small, cheap and smart enough to appeal to novices who just didn’t realise where those limits lay. And who – other than Turner – could blame them? If a road test said that a C15 had a top speed of 75mph, it must have seemed reasonable to try to achieve that on every occasion.

Matters were made even worse in 1960 when learners were restricted to quarter-litre machines. Naturally this meant a sales boost for the C15, but it also meant that learners thrashed the socks off them trying to keep up with their mates who had passed their test and graduated to big twins. Consequently, the little Beezas’ reputation became so poor that people in the trade dismissively referred to them as hand grenades, because of their tendency to go a short distance and then explode!

It’s true that some changes and improvements were made over the next few years, but they were mostly too little and too late. For instance, the contact breaker – which was admittedly very accessible – was initially located behind the cylinder where it was rotated by a worm drive. It soon became common knowledge that the drive mechanism was susceptible to wear, with predictable consequences for ignition timing, but it was seven years before the points were re-located in the crankcase where they could be driven directly from the camshaft.

Similarly, when a souped-up version of the C15 – optimistically called the SS80 – was introduced in 1962, it was given a roller bearing big end. But despite this tacit admission that the standard plain bearing wasn’t really up to the job, the cooking model wasn’t given the same upgrade until 1964. Surely any cost penalty involved in making the change straightaway would have been offset by economies of scale resulting from using the same assembly throughout the range. And BSA would have achieved increased consumer confidence and sales by making improvements before they became essential.

As it was, Small Heath concentrated on giving its young customers the increased power they demanded, and only made the necessary engineering changes when they were left with little alternative. For instance, it had long been realised that supplying the plain big end’s oil through a plain timing side bearing – another Edward Turner trademark – was only satisfactory as long as the bearings were in pristine condition. But it wasn’t until 1966 that the C15 and its sports derivatives were given the revised oiling system and robust ball bearing journals that had become essential on the bigger competition models.

As it was, Small Heath concentrated on giving its young customers the increased power they demanded, and only made the necessary engineering changes when they were left with little alternative. For instance, it had long been realised that supplying the plain big end’s oil through a plain timing side bearing – another Edward Turner trademark – was only satisfactory as long as the bearings were in pristine condition. But it wasn’t until 1966 that the C15 and its sports derivatives were given the revised oiling system and robust ball bearing journals that had become essential on the bigger competition models.

If all that sounds rather negative, it’s only fair to sympathise with BSA’s efforts to keep things going in a period when sales of motorcycles were dropping steadily. The company’s engineers obviously knew how to make better quality motorcycles that would last longer, but they had to prevail over their business colleagues who’d have argued that the consequent hike in price would accelerate the decline. Much better, the accountants would have suggested, to follow Edward Turner’s policy of making the bikes faster and better looking, as it would cost little, while continuing to attract young buyers. And they were probably right, because the quarter-litre singles were apparently the only BSAs actually produced at a profit during the 1960s.

And the evolutionary process had certainly resulted in some smart looking machines with impressive potential. The C15 had become the C25 in honour of its claimed rise in brake horsepower, and then – for no obvious reason – it became the B25. And along the way it was given evocative names like Barracuda, Starfire and – ultimately and ignominiously – Gold Star.

And the evolutionary process had certainly resulted in some smart looking machines with impressive potential. The C15 had become the C25 in honour of its claimed rise in brake horsepower, and then – for no obvious reason – it became the B25. And along the way it was given evocative names like Barracuda, Starfire and – ultimately and ignominiously – Gold Star.

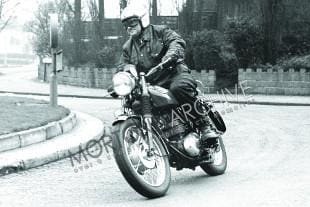

I’ve long thought that these later models might suit a mature modern clubman down to the ground. They have ample performance for the way most of us ride nowadays, and their improved mechanical integrity, coupled with our more sober riding techniques, should give them a long and trouble-free life. The trouble was that most of these variants were ridden into the ground, so when Eric Harvey turned up on a smart little B25S Starfire, I wasted no time in engaging him in conversation.

First off, I asked Eric why he’d bought the BSA, as he’s known to be a man who changes his bikes as often as most people change their socks, and I thought his experience with other machines might have led him to this purchase. Well it did, but not in the way I’d expected! “I only got back into bikes after a 40-year layoff,” he tells me, “because a mutual interest in radio-controlled helicopters led to me becoming friendly with Harvey Sims (whose Triumph/Greeves appeared in The Classic Motorcycle July 2000). We and our wives started camping at weekend country fairs, and I bought an Ariel Red Hunter to put on display at them. It wouldn’t fit in Harvey’s trailer, though, so I needed a smaller bike, and the B25 happened to be available locally at the right price!”

And apparently the BSA’s previous owner was equally subjective in his choice of machine, because he bought the B25S for his son to use, largely because he liked its colour scheme! Well, I must admit that the maroon is quite fetching, but I think that if I’d restored the Starfire I’d have gone for the usual vivid blue.

Anyway, if all that doesn’t tell me much about the motorcycle, it does point to Eric’s expertise, because the reason the BSA was available and affordable was that its previous owner couldn’t get it running properly. Eric – who was an aircraft engineer before spells as a market gardener and lorry driver – has fitted a new Concentric carburettor and advance/retard mechanism, so the B25 now starts reliably and ticks over like an old-fashioned five-hundred. He’s also modified the feet of both the stands, so the bike rolls onto its centrestand without a heave, and is supported at a sensible angle by the sidestand. Oh, and he’s fitted a 12-volt non-leak gel battery. “I bought it at a car boot sale “ he grins, “apparently its a time expired job from a burglar alarm, but it fits well, works fine, and only cost a couple of pounds.”

Anyway, if all that doesn’t tell me much about the motorcycle, it does point to Eric’s expertise, because the reason the BSA was available and affordable was that its previous owner couldn’t get it running properly. Eric – who was an aircraft engineer before spells as a market gardener and lorry driver – has fitted a new Concentric carburettor and advance/retard mechanism, so the B25 now starts reliably and ticks over like an old-fashioned five-hundred. He’s also modified the feet of both the stands, so the bike rolls onto its centrestand without a heave, and is supported at a sensible angle by the sidestand. Oh, and he’s fitted a 12-volt non-leak gel battery. “I bought it at a car boot sale “ he grins, “apparently its a time expired job from a burglar alarm, but it fits well, works fine, and only cost a couple of pounds.”

Besides detailing these deliberate changes, I’d better mention an apparent anomaly that experts in the breed may well have already noticed. The Starfire superseded the Barracuda in 1968, and early examples shared the older model’s GRP petrol tank. Well, this is not one of those as it has the steel petrol introduced on safety grounds in 1969. And yet it has the older style of single leading shoe front brake, instead of the twin leader that became standard at about the same time. Eric’s BSA was actually registered for the road in January 1971, so it may have been made with the improved stopper and been subsequently robbed of it. Or, quite possibly, it could have been made around the changeover date in 1969, and then simply lingered in the showroom until it was sold off at a discount when it was the Starfire’s turn to be replaced (by the Street Scrambler-styled B25SS Gold Star).

I must admit that my first impressions of the B25S on the road are not great, and that’s largely because of its peculiar seating position. Eric might have bought it because it’s short, but its dual seat is as vertigo-inducing as those on the later models with the reviled oil-bearing frame. And what’s more, the petrol tank – for all its racy quick action filler cap and sensual styling – has shapely indents that are in totally the wrong place for my knees, besides being so narrow that the sensation is more like straddling a gate than settling into a normal riding stance. Being charitable, I’ll put it down to the B25S’s relationship to previous off-road models like the Victor Enduro, as the seating position is very much like that preferred by scrambles riders of that era.

I must admit that my first impressions of the B25S on the road are not great, and that’s largely because of its peculiar seating position. Eric might have bought it because it’s short, but its dual seat is as vertigo-inducing as those on the later models with the reviled oil-bearing frame. And what’s more, the petrol tank – for all its racy quick action filler cap and sensual styling – has shapely indents that are in totally the wrong place for my knees, besides being so narrow that the sensation is more like straddling a gate than settling into a normal riding stance. Being charitable, I’ll put it down to the B25S’s relationship to previous off-road models like the Victor Enduro, as the seating position is very much like that preferred by scrambles riders of that era.

‘And while the front brake might not look as impressive as the twin leading shoe job that would be expected on this model, both stoppers are well up to their task.’

In compensation, the steering is light and positive and the Beeza inspires confidence, whether main-roading or bend-swinging. The steering lock is tight, too, and U-turns in country lanes present no difficulty. And while the front brake might not look as impressive as the twin leading shoe job that would be expected on this model, both stoppers are well up to their task.

And the engine is everything that you could ask for in a British two fifty. Its claimed 24bhp is produced at 8250rpm – an astronomical rate of revolutions for a comparatively unsophisticated push-rod single – and it feels as if it could actually do most of those revs without disintegrating expensively, and without risk of your tooth fillings falling out. At the same time it pulls remarkably well at low revs, and good progress can be made without feeling the need to keep things on the boil by changing down at each and every obstacle.

Testing a Starfire in 1969, the late great Bob Currie concluded that it was ‘really two machines in one’. He wrote that whether it was an ‘amiable, economical, ride to work 250, or a light and handy but distinctly peppy sports mount, depended upon the itchiness of your throttle hand’. As always, he was quite right; the B25S will trundle around in top gear while keeping to urban speed limits, or you can use the well-spaced gears to cover the standing quarter mile in 18 seconds and hit a maximum of nearly 90mph.

Testing a Starfire in 1969, the late great Bob Currie concluded that it was ‘really two machines in one’. He wrote that whether it was an ‘amiable, economical, ride to work 250, or a light and handy but distinctly peppy sports mount, depended upon the itchiness of your throttle hand’. As always, he was quite right; the B25S will trundle around in top gear while keeping to urban speed limits, or you can use the well-spaced gears to cover the standing quarter mile in 18 seconds and hit a maximum of nearly 90mph.

Other than a mild complaint that the ‘seat height could be cut down with advantage’, and that ‘to place both feet on the ground at a halt becomes something of a stretch for a rider of average leg length’, Currie didn’t comment on the riding position. So that either means that he found it OK, or decided not to kick the remnants of British industry too hard while it was down. He couldn’t, however, fail to admit that the stylish GRP panel that covers the oil tank digs into your thigh every time you use the kick-starter.

He also commented on the unfortunate siting of the ignition key at the front of the tool box, tight under the nose of the dual seat – it is awkward with bulky gloves. I’m told that setting the valve clearances through those little inspection covers is none too easy, either, but that’s yet another Edward Turner trademark that would have cost serious money to eradicate.

Still, those are irritations – albeit ones that you wouldn’t expect on such a long-established model – rather than serious complaints. What really mattered was that the B25S Starfire finally delivered what had been promised by the C15 all that time before. At long last, and rather surprisingly, BSA had managed to produce a lightweight motorcycle with a neat appearance, excellent handling and brakes, and very importantly, a remarkably poky motor that promised to do its stuff without self-destructing.

Still, those are irritations – albeit ones that you wouldn’t expect on such a long-established model – rather than serious complaints. What really mattered was that the B25S Starfire finally delivered what had been promised by the C15 all that time before. At long last, and rather surprisingly, BSA had managed to produce a lightweight motorcycle with a neat appearance, excellent handling and brakes, and very importantly, a remarkably poky motor that promised to do its stuff without self-destructing.

Sadly, what mattered even more was that in the intervening dozen years, committed riders had become used to paying a bit more for oriental motorcycles with electric starters and all the trimmings, while less enthusiastic riders had long since graduated to four-wheelers. Instead of proving to be the company’s salvation, the B25 range became just one more thing for the BSA/Triumph group to squabble over, and production ignominiously petered out in 1972.