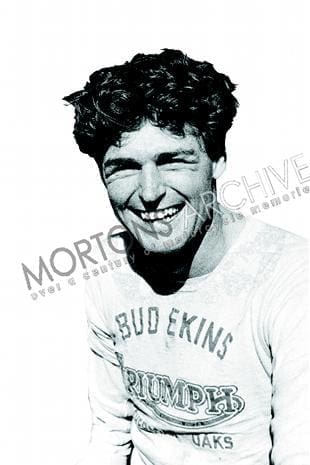

International scrambler, champion desert racer, ISDT gold medallist and Hollywood stunt rider – in a career which spanned five decades Californian Bud Ekins was them all.

For much of both his business and racing career, Bud’s name became synonymous with that of rasping Triumph twins but, as he explained, his riding began on a very different sort of machine.

“From 16, I was into hot-rod cars and I was 18 when I first rode a bike, which my cousin had bought. I immediately loved it, so went out and got one of my own, a 1934 1200cc side-valve Harley-Davidson.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

“At every opportunity I would take the Harley up into the Hollywood Hills, riding the dirt roads, ‘cow trailing’ as it was known. I got to know virtually every fire road, sand wash, mountain dirt-road and desert trail in the area and also got pretty good at sliding the bike around.

“My friends were impressed and encouraged me to have a go at a hare and hounds desert race, which was coming up. I didn’t really know too much about it, but racing against other people sounded fun so I thought I’d give it a try.”

This was 1949 and from the outset Bud looked a natural. It wasn’t long before he gave notice of what was to come when he notched up his first win.

“I’d bought this 500cc  Matchless which I’d entered in the desert endurance race known as the Moose Run. I was going pretty well and fancied my chances of getting by this guy on a sprung-hub Triumph. I eventually managed to overtake him on the long bumpy down-hill section which led to the finish. The chequered flag dropped and I’d recorded my first win.”

Matchless which I’d entered in the desert endurance race known as the Moose Run. I was going pretty well and fancied my chances of getting by this guy on a sprung-hub Triumph. I eventually managed to overtake him on the long bumpy down-hill section which led to the finish. The chequered flag dropped and I’d recorded my first win.”

That an ‘unknown’ 20-year-old had won the Moose against all of the established stars was an amazing achievement but to prove it was no fluke, Bud was soon adding to his collection of silverware.

He displayed a talent for winning which brought him to the attention of local Matchless distributor Frank H Cooper who, acutely aware that a ‘win on Sunday’ usually secured a ‘sale on Monday’, asked Bud to go and work for him.

Bud raced the Cooper Matchless in all of the important desert races including the Big Bear, which he would later go on to win no less that three times in the 1950s.

As Bud told me, it was while he was working and racing for Frank that he first became aware of the motorcycle scene in the UK, and scrambling on mud.

“Frank used to have the Blue ’un and Green ’un shipped over from England and I’d read them from cover to cover. It didn’t take me long to realise, ‘Oh boy, that’s where the motorcycling is’, so Cooper made arrangements for me go to Plumstead.

“AMC agreed that I could have a bike to race in some end of season scrambles, but I had to fund the trip and all my living and travelling expenses while I was there. I went to the factory competition shop and met up with guys like Hugh Viney, Jock West and Bob Manns who I’d read about in the magazines.

“Manns was still very active in both one-day and International Six Days Trials, but was coming towards the end of his scrambles career, so they offered me his works bike to race. I hadn’t thought how I might get the bike to the meetings, so somebody suggested I should ride it.

“Gee, can you imagine a young guy who’s never driven on the left before trying to find his way out of London on a strange motorcycle? I even got lost on the buses! Fortunately, Bob Manns took pity on me and agreed to take me to the scrambles in his van.”

The big man from Cal ifornia rode in about four events in the late summer of 1952, his all-action, never-say-die riding style soon making him a great favourite with the crowds. It whetted Bud’s appetite and, not surprisingly, he was back the following year, this time with fellow countryman Bernie Hancock.

ifornia rode in about four events in the late summer of 1952, his all-action, never-say-die riding style soon making him a great favourite with the crowds. It whetted Bud’s appetite and, not surprisingly, he was back the following year, this time with fellow countryman Bernie Hancock.

“We both rode Matchless singles, but this time they were just two bikes off the assembly line. They weren’t quite as quick and the suspension wasn’t as good as the works bike, but we did OK.

“We were in Britain for about two months and were racing every weekend, including three or four meetings in France. What with start and prize money I was earning about £25 a week, which was good when you consider the average wage then was about £4-£5.

“Geoff Ward (Ex-AMC works rider) used to deal in used cars so we transported the bikes in an ex-RAF Standard pick-up which we rented from him for £1 a day.

“We also found some good digs in London. At the end of Plumstead Hill was the Royal Arsenal co-op and behind it was an old mansion in Abbey Wood where we stayed. It cost us £3 a week including two square meals a day.

“People would ask us what we rode in the States and I would show them pictures of my bikes. They would immediately point and say ‘no mudguards’, to which I would reply ‘no mud!’”

On returning to his native California and armed with the riding skills honed in Europe, Bud was almost unbeatable in the domestic series, and was soon wearing the prestigious California ‘number one’ plate.

Such was his dominance he would go on to win this seven times, but it wasn’t just the racing skills he brought back from Europe. It triggered off his association with Triumphs, opened the door to becoming a dealer, kick-started his love affair with the ISDT and also launched an enduring friendship with Ken Heanes.

“I was racing the Matchless at a meeting in Wales when I was overtaken on the straight by two Triumphs, ridden by Johnny Giles and Ron Stillo. I thought I would get to the rough bits and catch them up but they’d all but disappeared. It was then I realised the writing was on the wall and I had to get one.

“I went back home and discovered that Cooper had given my job to somebody  else so I went working in my dad’s welding shop. Johnson Motors were the main Triumph distributors so I went to them and asked if they would let me have a bike. ‘Yes sir, you’ve got it’ was the reply, so from that time on I rode Triumphs. The same year – 1954 – I also opened my shop.”

else so I went working in my dad’s welding shop. Johnson Motors were the main Triumph distributors so I went to them and asked if they would let me have a bike. ‘Yes sir, you’ve got it’ was the reply, so from that time on I rode Triumphs. The same year – 1954 – I also opened my shop.”

In the 60s Bud’s became famous as the hangout for the famous and he laughed as he said: “If you wanted to go searching for a movie star you could either drive up and down Hollywood Boulevard all day or just pull up at the back of my shop – you could usually find one or two!”

Many of Hollywood’s biggest stars including Steve McQueen, Dean Martin and Paul Newman, would become both customers and good friends of Bud’s, but it took an intervention from Lady Luck to start things off.

“I was over at Meriden and happened to overhear a conversation from an executive who was saying that they’d lost their dealership in the Sacramento Valley.

“I approached the guy and asked if I could have the franchise to which the answer was yes. I didn’t have much money and by the time I’d sorted out some premises and got things up and running I was almost broke. Triumph was great and put all of the bikes on the forecourt and stocked me with tyres and spares. I think it took me about three years to pay it back. I was 24 and probably the youngest Triumph dealer anywhere in the world.”

In the fullness of time he would also become one of the largest and by the early 60s would be selling 700 to 800 new bikes a year. The word in Hollywood then was that if you were a star you had to have a bike, if you had a bike it had to be a Triumph and if it was a Triumph then you had to get it from Bud’s!

His domination of the California desert circuit continued. In 1955 he won the prestigious Catalina Grand Prix, slicing a staggering 10 minutes off the previous race record, and in one of his Big Bear victories he completed the 153-mile course more than half-an-hour ahead of his nearest rival – this despite suffering a flat tyre and damaging the rear wheel in an event which attracted nearly 1000 riders.

He still found time to make visits to Europe and he recalled racing in the Berkshire Grand National where, after pipping Ken Heanes at the post, he was cruelly robbed of victory.

“There was field of about 25 or 30 and by the end of the first lap I was running in about seventh place. I gradually moved up to second with just Ken Heanes ahead of me. I hung back until the last corner where I made my move and overtook. There was no time for Ken to respond and I secured what I thought was my first win in England. I was just about to celebrate when an official came up and said ‘I’m sorry, Mr Ekins, but there was a mistake with the lap scoring, you did 11 laps instead of 10, so you’re second.’”

For many of us in Europe, Bud became famous for his exploits in the International Six Days Trial, so I asked him what got him interested riding in it.

“I’d read about the ISDT in the ‘Blue Un’ and ‘Green Un’ when I was at Cooper’s but it wasn’t until I came to Europe and went to AMC that I realised how important it was to them.

“I met Hugh Viney, Bob Manns, Ted Usher and Gordon Jackson who would be preparing all year for the September event and several times we all went to Jacko’s farm together practicing. It sounded such a great event I thought that some day I’d better come back and give it a go.”

With his shop up and running Bud did indeed come back and ‘give it a go’ at the Welsh event of 1961 in Llandrindod Wells, although he was not the first American to ride in the ISDT.

As early as 1949 fellow countryman Tommy McDermott had competed in the trial which, coincidentally, was also based in Llandrindod Wells. BSA-mounted McDermott was taken under the wing of works rider Billy Nicholson and after six days of slog was rewarded with a gold medal for his endeavours.

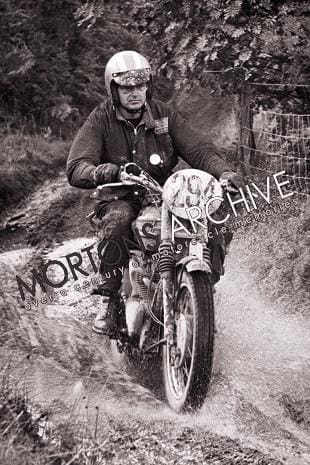

Walt Axtheim on a Jawa and Vern Hancock also tried their best without success in the event in Austria in 1960, but for 1961 Bud was joined by Jim Brunson and Lloyd Lingelbach, who were both riding 250cc Greeves. Not surprisingly, Bud was mounted on a 650cc Triumph prepared by the competition shop at Meriden and was soon wowing the crowds with his all-action riding style. Held in superb weather he was on course for gold until the last day when disaster struck.

Walt Axtheim on a Jawa and Vern Hancock also tried their best without success in the event in Austria in 1960, but for 1961 Bud was joined by Jim Brunson and Lloyd Lingelbach, who were both riding 250cc Greeves. Not surprisingly, Bud was mounted on a 650cc Triumph prepared by the competition shop at Meriden and was soon wowing the crowds with his all-action riding style. Held in superb weather he was on course for gold until the last day when disaster struck.

“I was going real well but on day six the gearbox got jammed in fourth. I had to take the outer cover off and discovered the little pawl had stuck. I clicked it back into position and was away again in 12 minutes.”

Bud rode like the wind through the Welsh forest tracks in an attempt to make up for lost time but, frustratingly, got to the time check an agonising minute outside gold medal schedule!

“My goal had been to win an ISDT gold so I was pretty peeved to end up with silver. Who knows? If I’d won gold in that first event I might not have done another one.”

Not only did Bud return for the 1962 event in Garmisch-Partenkirchen, he did so in some style, winning not only his sought-after gold, but also finishing first in the hotly-contested 750cc class beating the entire BMW factory team in the process.

It was during this time that he added stunt rider to his impressive resume of shop-owner, desert racer and ISDT star. It came about when he joined his great pal Steve McQueen in the filming of The Great Escape.

It also triggered off events which led to America’s first team-entry in the East German six days of 1964. The team comprised Bud as captain, his younger brother Dave Ekins, Steve McQueen, Cliff Coleman and reserve John Steen. I started by asking Bud about that famous leap for freedom, a jump often wrongly attributed to McQueen. “Steve was in Germany filming The Great Escape when I got this letter inviting me over to perform some motorcycle stunts which the insurance people wouldn’t allow him to do.

“At that time he was one of Hollywood’s biggest stars, so you can imagine the repercussions if he’d injured himself and been laid up for three or four months. It was perfect timing for me because the ISDT was coming up so it meant I could go to Europe and take a break during the filming to ride in the trial.

“At that time he was one of Hollywood’s biggest stars, so you can imagine the repercussions if he’d injured himself and been laid up for three or four months. It was perfect timing for me because the ISDT was coming up so it meant I could go to Europe and take a break during the filming to ride in the trial.

“I was five inches taller than Steve but when they cut and bleached my hair and dressed me in the same style clothes you couldn’t tell the difference. The bike was a stock ’62 Triumph which weighed in at about 400lbs. I jumped a distance of 65 feet over the 12-foot high wire and all the filming was done in just one pass. I’ve got a feeling it was the first $1000 movie stunt.”

Between shooting, a lot of bike-talk took place especially regarding the ISDT and by the time filming was completed McQueen was keen to compete in the ‘motorcycling Olympics’.

By virtue of their victory in Czechoslovakia the previous year, the honour of hosting the 1964 trial fell to the East Germans. I asked Bud what he remembers about the preparation for the event.

“Steve was, perhaps, the least experienced of our team, but he was incredibly enthusiastic and he spent a lot of time practicing and racing in desert events. He was a very useful rider and after completing The Great Escape, he took the whole year off preparing himself for the ISDT, including coming to work in my shop. Much of the time he was there he was changing tyres and got so quick he could do one on a Triumph in about four minutes.”

The Americans were to be mounted on Triumphs and came to England to practice ahead of the September event, enlisting British team captain Ken Heanes in their preparations.

Bud’s team-mates had little or no experience of racing on mud, so Ken took them to central Wales where they found plenty. After demonstrating how to negotiate a typical Welsh bog, Ken waved Steve forward to have a go. He hit the mud at high speed and promptly disappeared over the handlebars. Covered from head to toe in green slime he got up with a big, cheesy grin and apparently said: “Gee, do you think you could show me that again, Ken?”

The machines were short of the specification to those supplied to the British team and were taken to Comerfords at Thames Ditton, where the Americans were given free run of their workshops.

With fettling and improvements carried out, they set forth in the Club America van which team manager Ted Wassel had secured from Triumph dealers H&L motors, Wassel following closely behind in his Jaguar car. All went well until they arrived at the heavily guarded border post, as Bud explained.

“When we got to the East German b order we were held up for about four hours while they checked our passports. Remember, this was at the height of the Cold War and it wasn’t everyday they had Americans wanting to enter – especially when one of them was a big Hollywood star. I think they had to phone Berlin to make sure that Steve had never made any anti-Communist movies before they let us through!

order we were held up for about four hours while they checked our passports. Remember, this was at the height of the Cold War and it wasn’t everyday they had Americans wanting to enter – especially when one of them was a big Hollywood star. I think they had to phone Berlin to make sure that Steve had never made any anti-Communist movies before they let us through!

“We had to pass through about four miles of no man’s land and were given strict instructions of ‘no stopping and no photographs.’”

Despite their lack of ISDT experience, the American team performed extremely well and by end of day three were all on gold medal schedule and leading the Silver Vase class. Sadly on day four, both Steve and Bud suffered crashes and although Bud managed to get to the finish, he was diagnosed with a broken ankle. With McQueen’s bike too badly damaged to continue, both men had to retire. Although the team were out of contention Dave Ekins and Cliff Coleman each went on to win gold and John Steen, silver.

The story of Hollywood behind the Iron Curtain is well documented in Sean Kelly’s book 40 Summers Ago and during the course of our conversation, Bud told me enough tales to fill another volume – stories of MZs being overhauled in a van, minders waiting in woods and a route marking system which favoured the home team will have to wait until another time, as I was intrigued to know how Kelly’s book came about.

“A girlfriend of Sean’s is a neighbour of mine and one day she offered to sort out some of my stuff including my boxes of photos, which were all jammed under my pool table.

“She was sticking them into albums when Sean happened to come by and saw a photo with McQueen sitting on his ISDT Triumph. With a magnifying glass Kelly could read the engine number and discovered that the bike still existed.

“Not only did he manage to buy the bike from its then owner Frank Danielson in Sacramento, the photograph albums triggered off the idea of recording the ’64 ISDT to print.”

Throughout the 60s, Bud continued to ride in the ISDT and after the disappointment of a DNF in the waterlogged Isle of Man event of 1965 he added to his collection of golds in Sweden in 1966 and the following year in Poland. By now, the heavyweight Triumph twins were no longer competitive and Bud had switched to two-stroke Husqvarnas. He continued to balance stunt work with running his shop and desert enduros and was a founder member of the Baja 1000 race along the Mexican peninsula.

After the best part of 20 years of top class racing Bud hung up his leathers, sold the shop and concentrated on stunt riding – needless to say, given his pedigree he became one of Hollywood’s best.

If you’ve ever seen the film Bullit, Bud was the rider who laid the bike down under the truck and he was also the driver of the Ford Mustang. He eventually retired from stunts in 1997 and since then has concentrated on restoring his ever burgeoning collection of motorcycles, all of which get ridden regularly, ‘cow trailing’ along those favourite dirt roads in the Hollywood Hills.

Bud is undoubtedly one of motorcycling’s great characters and it was a privilege to spend some time talking to him. Incidentally, the friendship with Ken Heanes, which started at Aldworth and the Berks GN in 1955, has endured to this day and Ken is presently rebuilding restoring a Triumph Tiger 110 for Bud to ride in this year’s Irish rally.

Bud Ekins obituary – The Classic MotorCycle, December 2007

All-round American motorcycling legend Bud Ekins has died, aged 77. An international scrambler, champion desert racer, ISDT Gold medallist, motorcycle dealer and Hollywood stuntrider, over a five decade two-wheeled career, the remarkable Ekins’ adventures spanned all those genres and more.

Despite becoming synonymous with Triumphs later, it was in fact a Harley-Davidson that Ekins first learned to ride before switching to a Matchless, on which he recorded his first win as a 20-year-old and impressed enough to gain support from Matchless distributor Frank Cooper.

It was Cooper who introduced Ekins to the Matchless factory and the young man came to England to race in 1952 – the success of the venture encouraging him to return in 1953. With the experience gained, on his return to the US and now armed with Triumphs, Ekins became almost unbeatable. Around the same time, he opened his first dealership.

The Ekins’ shop became a hangout for many movie stars, with Steve McQueen, Dean Martin and Paul Newman among those who Ekins could count as friends as well as customers.

Since his early 1950s visits, Ekins had been back across to Europe several times to race, though it was the ISDT that had captivated him and at which he wanted to have a go. His wish was granted in 1961 when he made his debut, on a Triumph, narrowly missing out on a gold. He was back the next year, though, clinching the gold medal, and around this time he also started his stunt career, standing in as Steve McQueen’s double during the famous ‘jump scene’.

Further ISDT golds came Ekins’ way – making four in total – as did more stunt work and even more desert racing victories. Eventually, Bud sold the shop and quit racing to concentrate on the stunt career, which he continued until 1997. Since then, he spent his time restoring and riding his old motorcycles.