Carlsberg never made classic trail bikes but if they did, it would be just like this: Yamaha’s sublime DT175 twin shock.

Words: Steve Cooper Pics: Gary Chapman

There cannot be many classic motorcycle fans who haven’t encountered one of Yamaha’s seminal DT175s or its precursor the CT1/2/3 form range. Whether you rode one or knew someone who owned one, most are more than aware of the bike.

Back in the day the 175 single was everywhere; they were ubiquitous, yet fast-forward a decade or so and many had been ridden into the ground… sometimes literally.

The twin shock trail iron was pensioned off in favour of the DT175MX with its hugely competent mono-shock rear-end and anyone in the market for a lighter-weight trail bike almost immediately bought into the new technology. The MX was hugely proficient at what it did and, arguably, highlighted the older bike’s shortcomings leaving the twin shock looking decidedly unloved. Those that weren’t trashed as field bikes probably ended up being given to the local scrap man. Simply put, twin shock Yamaha DT175s are rather rare birds now and to find a UK example that hasn’t been bodged, bastardised or broken is something of an event these days. And finding one from the last years of the model is truly unusual.

We’re back again raiding the garage of Dave Payne and as I’ve come to realise his bikes are genuinely ‘on the button’ – and the DT175 is no exception. Yamaha may have played around with the DT’s cosmetics over the years but the basic profile hardly changed at all. If someone had created silhouettes of 1970s trail bikes you’d have been able to spot the DT175 in an instant.

Almost everything is neatly tucked away and out of harm’s reach, allowing even the numptiest teenager to attempt a modest off-road foray. The footpegs are hinged ready to fold in the event of an off; the exhaust system is notably tucked out of the way; and there’s a small bash plate aka sump guard that stops the flora from getting caught up in the space between the crankcases and frame tubes.

Looking over the bike critically there’re just three areas that would take a strategic hit in the event of a tumble. The rear brake lever is tucked in as tight as possible yet could still get bent in a fall, but what else could you do with it? On the opposite side the gear lever sticks out like the proverbial sore thumb and is prime ‘Saturday morning at the Spares Department Counter’ fodder. Given its fundamental importance you can’t help wondering why, for a handful of yen, the tip isn’t pivoted and sprung loaded… surely that would have made sense? The components guaranteed to relieve you of money are the rear indicators which are hung out in the breeze ready to make intimate contact with anything in their near vicinity – plastic ones on bendy stalks were still a few years away. None of which are direct criticisms – these were the compromises made at the time in order to be able to take a road legal (and practical bike) off-road.

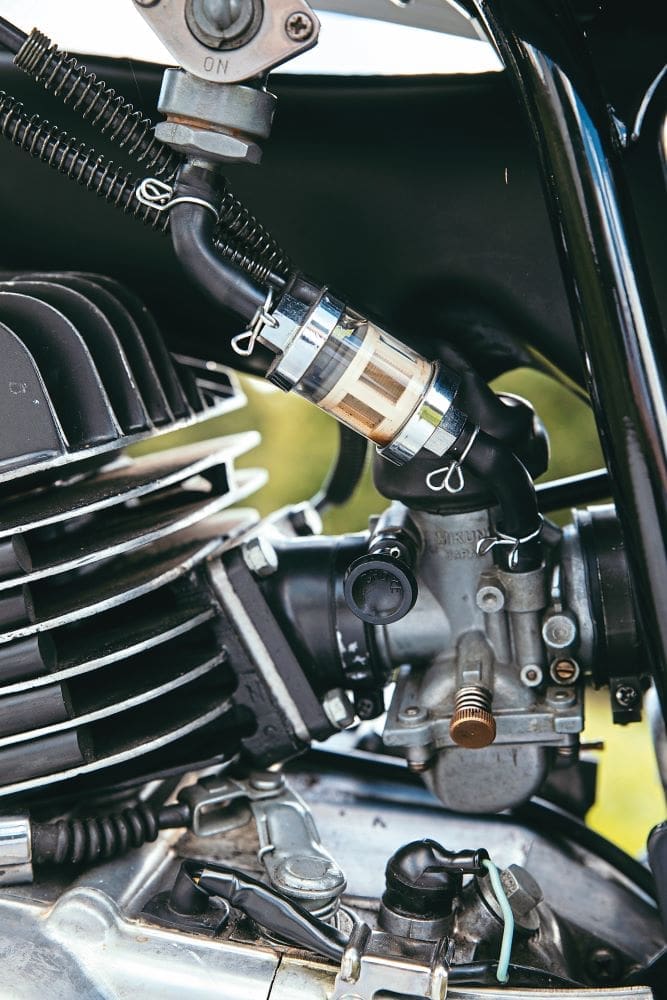

Our test bike exemplifies Yamaha’s mindset of the period. The gauges are chrome bodied as was pretty much everything in the firm’s range and their faces are in that indiscernible grey/blue and typical of the time. Switchgear is effectively generic and again common on many models, and it’s a similar story with the indicators and probably the headlight as well. What’s unique to the model is that serpentine exhaust system which is substantially more convoluted than that of the original CT’s. To get the front pipe length correct it has to execute a 180-degree down and up before taking another 90-degree swoop rearwards and disappearing under the seat and behind the Autolube tank before twisting outwards to the left to reappear between the rear shock absorber and seat rail.

The design is substantially more complicated, and presumably more expensive, than the early CT set up, but shows Yamaha were conscious of the old format’s vulnerability. It was obviously a tight squeeze as evidenced by the trimming of the cylinder head’s fins rear on the right-hand side. The engine’s finish of polished outer cases and satin black cylinder/head was probably as much for cost saving with the former as it was practically with the latter. Paint-wise, the style is simple but effective in gloss white that extends to the guards and oil tank.

From an engineering and construction perspective there’s nothing on the bike that hadn’t been seen before. In essence, and like many of its contemporaries, the DT175 represents the Japanese business idea of ‘continuous improvement’, i.e. if it’s not broken don’t try to fix it but by all means enhance and improve what’s there. This rationale is the reason for the rerouted exhaust, the sound deadening rubbers between the fins of the cylinder, and the strategic use of common components, etc. Only the minimum of DT specific components had to be made especially for the bike, thereby giving economies of scale, i.e. you’d find the control lever rubbers on a raft of period Yamahas.

Reputation only got you so far, which is the prime reason for year-on-year aesthetic revisions… no one wanted last year’s bike if this year’s looked better/funkier/sexier, etc. Appearance was hugely important in garnering sales, hence the left-hand logo proclaiming ‘Enduro’ even if such an appellation was more artistic licence than fact. Cast an eye over the DT and you begin to see a fair amount of shiny chrome, some of which wasn’t strictly necessary. However, when your target market was image-conscious teenagers a splash of bling here and there was like something sparkly to a magpie. Looks sell!

Riding the DT is so simple – pull out the choke button on the Mikuni, turn the fuel tap on, one clockwise turn of the key and kick through. You’re instantly rewarded with a nice throaty burble from the tail pipe and the obligatory puffs of partially combusted two-stroke oil. It doesn’t take long for the motor to be warm enough to dispense with the choke and you’re good to go as the Americans say.

You sit on top of the DT175 and it’s not a bad place to be compared to some trail bikes I’ve ridden because that seat is deceptively comfortable. The ergonomics of what is, after all, a relatively small motorcycle are better than you might expect, indicating it’s very much a rider’s machine with a design aimed at regular road use and not consistent forays into the back of beyond.

Just like other DT175s I’ve sampled the motor delivers its power with silky smoothness. It’s almost as if a turbine or an electric motor (perish the thought) is driving the rear wheel.

The gearbox works seamlessly and although not quite as slick as a Suzuki’s is still impressive in action. I’d go so far as to say that the DT175 is a seriously refined piece of kit, yet it’s never bland or lacking in character. Willing, enthusiastic and encouraging – all of these adjectives and more are totally applicable.

I didn’t take David Payne’s bike off-road but I have with other DT175s and can confidently state they are more than capable of putting a huge grin across your chops. Okay, so a seriously muddy track would probably curtail the fun and marshy bog could be its nemesis. However, stick to drier routes and you’ll be having a grand day out. On the Tarmac the bike is peppy, very flickable and arguably less hassle to ride than a ‘full size’ 250.

The reasons for the model’s success are manifold. Price and looks must have been prime drivers but the bike’s very solid reputation doubtless helped move used examples off dealers’ showroom floors and stock sheets – it was notably difficult to really kill a DT175 unless you ran it without oil.

For a dual-purpose machine the DT175 made a really fine road bike and transported countless teenagers to and from work, college, local youth clubs and pubs.

Perhaps, and not wishing to raise the ire of our home-grown bikes, if the likes of Villiers, AMC and/or BSA designers had been given the resources things could have been different. By revamping their stroker singles they might very well have got bums on seats and stemmed the canker that ate away at the British bike industry.

Back to the DT, it’s easy to see why it proved to be probably one of Yamaha’s best-selling trail bikes in Europe. With a substantial increase in grunt over its 125 sibling and carrying significantly less mass than its 250 bigger brother, the 175 was arguably the best of the bunch.

And if you’re in any doubt off that try cadging a ride on one and tell us it’s not one of the most well sorted twin shock trail bikes ever made!

The owner’s view by Dave Payne

When I was 17 I rushed out and bought an almost new XT500. I had it for five days before it was stolen from Luton College!

I still needed to get to work, so until the insurance paid out I bought a little DT175 as a runaround. It was great. I kept it after I was paid out and used it every weekend off-road. It became more and more disreputable but just kept going. My Dad would never ride my bikes as they were Japanese and consequently rubbish (not quite his words). Then one night I came home and he told me he had ridden “that little bike”. He was amazed: “Faster than my Ariel,”… his bike of choice since he was 16! After that he rode every bike I owned: VMaxs, GPZs, all of them.

When my Dad passed away, I thought it would be a great idea to find another DT175 as a sort of tribute to the little bike which brought me and my Dad really close. I had purchased one to restore then, trawling through eBay one day, back in 2009, I saw a really nice one advertised. It had been restored and had loads of NOS stuff brought for it. My son, James, and I went to look at it. We bought it and paid far too much for it… I told James at the time that if he ever told his mum what we paid for it, we were going to die! I had to sort a few little niggles and incorrect parts, but it’s been a great bike and always reminds me of those special days with my Dad.

Yamaha 175 trail bike genealogy

The 175 CT-1 first appeared in 1969 and was a simple reworking of the existing AT-1 125 of the same year and built with the minimum of 175 specific components.

A 10mm overbore delivered 3.5 more horses at 15bhp. Sold into the 1971 model year, the bike received a few revisions and cosmetic upgrades before morphing into the 1972 CT-2. The 1973 CT3 boasted Yamaha’s new reed valve induction system which massively enhanced the induction cycle and aided torque delivery.

Part way through the 1973 season all the trail bikes were redesignated as DTs with the CT-3 becoming the DT175. This was the start of the models being imported into the UK by Mitsui Machinery along with the AT-3 that became the DT125. Around this time the front wheel changed from 19 inch to 21 inch. Other than considered tweaks and cosmetics the DT175 changed little up until 1977.

The 1978 model year saw the introduction of the MX style with major changes to the chassis and running gear, most notably the use of a mono-shock rear end in place of the old twin shock layout. The bike was well received and the 21-inch front wheel now worked well with the new rear suspension increasing ground clearance, which had proved to be the earlier bikes’ Achilles Heel. Period road tests of the DT175MX against Suzuki’s TS185 and Kawasaki’s KE175 regularly put the Yamaha at the top of the pile due to its all-round ability and lack of significant foibles.

Sales of the DT175MX remained buoyant until the early 1980s when the introduction of the 125cc learner law effectively made the 175 redundant. Despite its cessation in the UK, DT175-based machines still enjoyed robust sales in the competition markets where the true Enduro IT family thrived.

The IT175 ran from 1977 through to 1985, offering some 23.5bhp against the best DT175 rated at 16. Increasing the stroke from 50mm to 57 saw the bike stretched to pretty much its limit and rebranded as the IT200.

After this, all the subsequent Yamaha trail bikes were completely revised and given liquid-cooled engines with the DT200 taking over from the DT175MX. The new motor delivered some 33bhp, which was far in excess of what the old air-cooled motors were capable of.

One final hike to the new motor saw the DT230 Lanza sold in various countries but sadly not in the UK. The final DT230 was unquestionably leagues ahead of the old CT range but, arguably, its looks were anodyne and sterile compared to its ancestors.