Steve Cooper falls for the charms of Suzuki’s second 750 four: the GSX750.

WORDS: STEVE COOPER PICS: GARY CHAPMAN

In a world of early 1980s UJMs (Universal Japanese Motorcycles) what do you do to stand out from the crowd?

How do you make a three-quarter litre machine look different from that of your competitors? Fancy paintwork is the usual route but what if you were to apply a little lateral thought here? How about putting all the various gauges, idiot lights and the like in a big binnacle then mounting that over a rectangular headlight?

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

Back in the late 1970s one of Suzuki’s design team had probably been playing around with the idea for a while when his boss asked for ‘something fresh and different’ – well they certainly got that!

Some 35 years on, the front end of Steve Hamilton’s GSX750 is still a topic of conversation which still splits opinion. Good or bad? Stylish or ugly? As CMM readers that’s your call but in the words of Oscar Wilde: “There’s only one thing worse than being talked about and that’s not being talked about!” Fair point, etc., and most of us have come to accept the look three decades on. After all, rectangular headlights were a ‘thing’ on 80s cars so why not have them on bikes? And for those who still take issue with the front-end of the GSX, know this – it could have been a whole lot worse. Google XJ750 Seca and look at just how out of kilter Yamaha’s offering was. And yet all of this misses the point entirely because what the GSX750 is really all about is that engine which was the natural successor to the old GS750. First off, the numbers of valves doubled from eight to 16 to aid breathing.

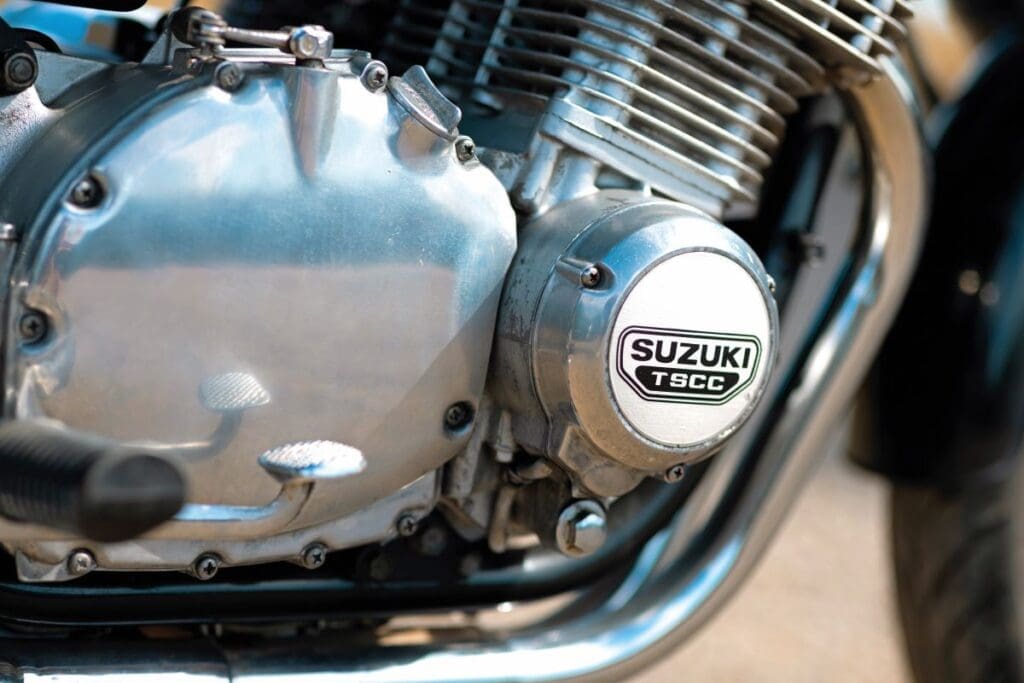

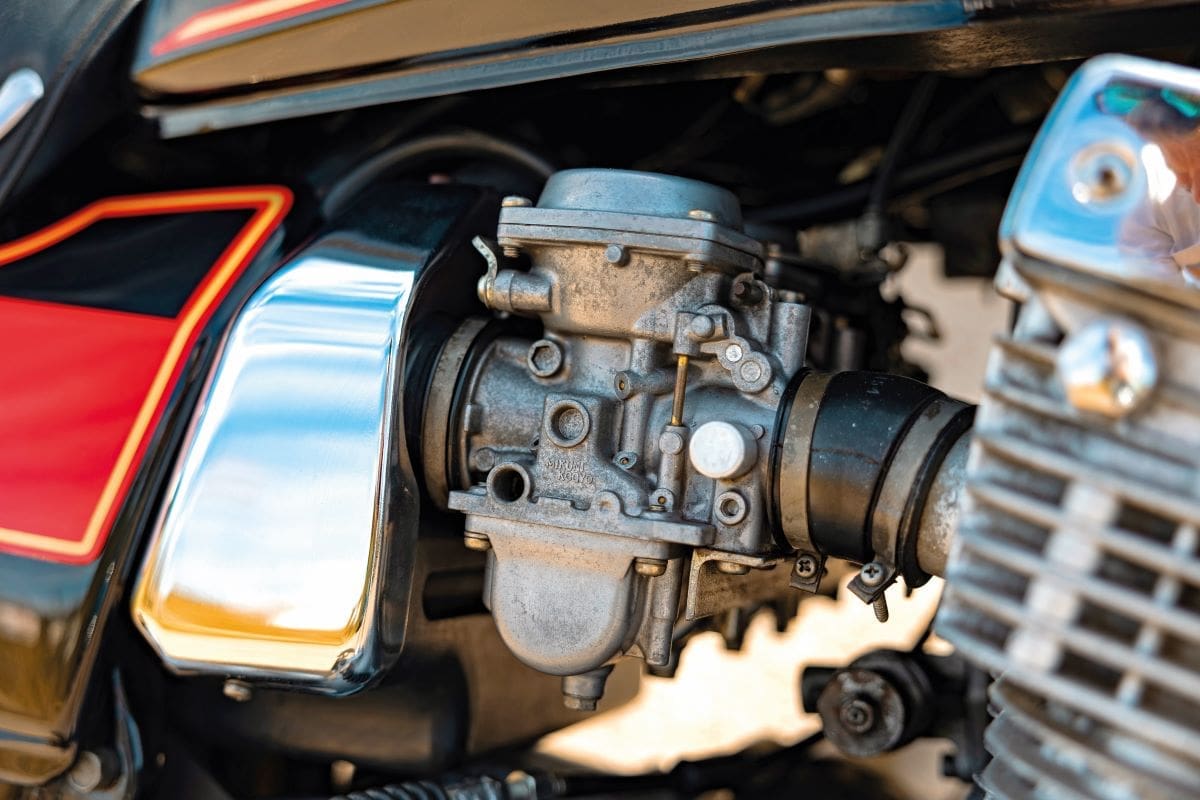

Next was the introduction of a new cylinder head design that was complemented by dedicated flat-topped piston crowns with valve pockets. Marketed as the TSCC aka Twin Swirl Combustion Chamber engine, the design increased the fuel burn speed via better flame front propagation. The result was transformational with the new GSX motor producing more power and torque. The journalists of the day were seriously impressed, eulogising about the changes over the old motor. Some even picked up on the fact that Suzuki had brought in outside help in the guise of consultant Italian engineer Vincenzo Piatti why had masterminded the new top end. Latin Vincent’s ideas would influence the firm for a long while with the TSCC technology used on the larger GSX1100 and many smaller bikes in Suzuki’s ranges. Also it would aid countless sprinters and drag racers to victories and inspire legions of special builds around the world. When the likes of Harris and Bimota used the 750 or 1100 motors in their bespoke chassis it totally ratified the work that had gone into the power unit’s top-end.

The running gear of the outgoing GS750 was never bad and at its launch the press were impressed by the bike’s handling. The GSX version’s frame simply improved on what already existed with subtle honing and refinements but it was the aesthetics that had really changed. The GS750’s looks were always safe, restrained and subdued, but not the GSX’s – oh no.

The old model’s tail-piece had, arguably, always looked like an afterthought but on the new bike it was sleek and blended in visually, flowing into the side-panels with their bold new badges. Suzuki had even worked the rear light into the tail piece’s profile for a more rounded homogenous look. The new fuel tank looked physically larger, reinforcing the impression that this was a totally new model and not a cunningly styled makeover – Suzuki was effectively distancing itself from the old GS750. Throw in some rectangular indicators to match that headlight and the GSX750 was definitely a machine for the 1980s and not a late 1970s throwback – but had the firm taken the looks too far? The bike stayed substantially unchanged over its three-year model run but the final iteration saw a conventional pair of gauges and a round headlight fitted. Perhaps the look had been just a step too far for some more conservative buyers who were put off by that striking look?

Meanwhile, back on our Classic Ride I’ve thrown a leg over the bike and settled into the seat. First impression is that it’s no lightweight and appears to carry its mass relatively high up. Second on my radar is that the tank feels wider than I’d expect but not uncomfortably so just… wider. First gear goes in with a bit of a clunk and I notice some of the lower ratios are similarly a little mechanical but we’ll put that down to age and possibly a transmission shock absorber that’s hardly in its first flush of youth – that’s old bikes for you.

There’s a lot going on under those cam covers and the TSCC top-end isn’t the quietest out there. It’s not badly-adjusted-valves noisy or damaged-cambearings thrashy, just mechanical – thus is the nature of the beast, as they say.

The riding position is a huge leap on from the sit-up-and-beg stance of the GS750 with relatively high foot pegs and lowish bars. Latterly perusing the riding shots expertly taken by Gary ‘the Lens’ Chapman, it doesn’t look like a particularly radical posture yet it certainly feels miles away from the baseline of anything before it. And perhaps this was one of the GSX750’s attractions when it was new – it feels sporty but it’s not cramped or uncomfortable.

That wide tank now makes sense and feels just right between your knees, and the seat is one of the best I’ve sampled from that 70s to 80s crossover period. Compared to what had gone before I’d say the bike in camera offers a sophisticated ride for the period combined with a singularly unique style.

Once fully accustomed to the bike it’s time to open the taps and get a better understanding of that motor. The sales pitch of 1980 made much of the TSCC’s ability to deliver improved power and torque, and even if the dynamometer readouts don’t really shout this from the rooftops there’s definitely a different feeling to this particular 750/4. Having sampled both Kawasaki’s GPz750 and Honda’s CB750F I’d happily go on record stating the Suzuki’s power unit is ‘the one’ to have. I’ve not sampled Yamaha’s XJ750 (please write in if have one we can ride) but I’d reason it would match the Suzuki’s motor. Yes, obviously, we comparing four-valve heads with two-valve units but so were the bike- buying public of the time and this why the GSX750 proved to be so damn attractive in the showrooms.

In summary I’d have to argue that the notion of the UJM was a convenient construct by the journos of the day suggesting all within a certain capacity bracket were worryingly similar. In reality they all retained their individual characters and traits and none more so than here. That GSX motor with its TSCC heads has a unique way of making power, which I, at least, find different to the GPz and CB. Power up to six grand is strong and predictable and then there’s a dramatic surge as the marvels of Ing. Piatti’s flow dynamics kicks in. It’s pretty good on the 750 so I’m betting on the GXS1100 it’s even more impressive.

So, aside from that uniquely designed motor what are the other sensations of the Suzuki GSX750? First up – and apologies for mentioning it yet again – is the instrument binnacle. It’s still impressive today so back in 1981 it must have seemed like something from Captain Kirk’s USS Enterprise; from the rider’s perspective it’s effective and does exactly what it’s supposed to.

Some have said the GSX is a weighty beast but looking at the specifications for the period it’s not especially meaty – it just gives a subtly different impression. The front brake lever has a strange feel to it but, apparently, they’re all like that. There is plenty of travel before anything whatsoever happens and then the brakes begin to engage. It’s almost as if the lever’s fulcrum is in the wrong place or the end that pushes the master cylinder’s piston in is too far away from it.

The front brakes are okay and up to the task yet very much of the period and a little remote/wooden/vague, but that said once you’re accustomed to them there are no dramas or worrying moments. The back brake is precise and predictable. One surprising facet of the bike is the level of exhaust noise coming from a perfectly good stock system. Thinking about America’s pernicious EPA regulation of the time, the bike’s audible emissions must have pushed the test procedure to the limit. However, here in Blighty it sounds absolutely gorgeous!

Perhaps what surprised me most was just how ‘together’ the GSX750 felt and how different from other 750s of the period the riding experience was. Kawasaki’s GPz900R is said to be the first machine truly designed as a single entity where engine and chassis designers worked together. Historically in Japan before the Ninja the running gear and power unit had each been designed as separate entities with only cursory liaison between the two. Well, that’s the accepted wisdom anyway.

And yet looking back at period tests many had said just how well the engine and frame of the old GS750 had complemented each other. I’d respectfully suggest Suzuki was already (and perhaps subconsciously) playing a ‘one team – one goal’ routine before Kawasaki came up with the idea. That it then refined its working practices further to deliver the frankly rather impressive GSX750 may have just been a case of an Oriental Continuous Improvement Programme. And I for one am pleased that it did because it really is a thoroughly well-thought-out piece of kit.

Owner’s story – Steve Hamilton

I purchased this Suzuki GSX750ET in 2021. It’s an American import from 1981 and was first imported into the UK in 2016 from Wisconsin. The bike is in a very original condition, with a little age-related patina, but I think it looks quite good. It has the original exhaust fitted, which for this bike is incredibly unusual. I purchased the bike from a guy I met on Instagram. He brought the bike for his dad to ride, as he used to own one in the early 1980s. However, I think his dad found the bike a bit heavy and struggled to use it. To be fair, it is a heavy bike for a 750 but I guess all Japanese muscle bikes from this era were. The previous owner managed to source a NOS Euro-shaped fuel tank and painted the bike in the colours of the bike his dad owned.

I drove up to Cheshire to test ride and collect the bike in my van, but just as I got to my destination, heavy snow started falling, so the test ride went by the wall. However, the bike still ended up in the back of my van on the way down to Hertfordshire. It’s a handsome machine and has early 1980s styling: the square headlamp, Ford Granada style, was a short-lived fashion trend in biking, but there is something quite quirky and quaint about it. I like it!

I’ve actually really enjoyed the bike, and done several thousand miles on it, including a tour to Belgium with friends last year. It’s not a mega-powerful bike, but it is an enjoyable ride. The engine is smooth, and there is a noticeable power surge after 6000rpm. The exhaust note and engine noise are delicious, particularly at higher revs. On long journeys, my ancient body finds the bike a bit tiring. Clearly, there is no wind protection, and the low bars do put a bit of excess weight on the wrists and back. The foot pegs are quite high in relation to the seat, and after 40 years in the plumbing and heating industry, my knees do not like that much at all! The seat, however, is plush, and really comfy.

I attended a Suzuki Live track day at Cadwell Park, and despite giving the engine a good thrashing for 90 miles, it never missed a beat. The real weak point on track were the period brakes, and the lack of ground clearance. I wore away both sides of the centre-stand. Despite this, the bike actually handled really well.

Investments, returns, issues and names

The basic, naked version of the three-quarter litre GSX only ran from 1980 to 1982 but Suzuki cannily made much more out of the original bike. 1983 through to 1987, the design gained a half fairing and the firm’s Full Floater rear suspension system. Thus equipped, the bike was marketed as the GSX750ES and at the same time offered a fully-faired version sold as the GSX750EF. Very much in the making-hay-while-the sun-shines mindset, Suzuki also equipped the 750 with Katana bodywork, further expanding the basic bike’s appeal without having to do too much in the way of actual redevelopment. The original GSX750 didn’t have too many real issues but the one constant that plagued it and many other Suzuki models of the period was the electrical system. The factory insisted on using a strange wiring system that compromised regulator/rectifier units. This led to overheating of alternator connectors of the LH switch assembly; always worth checking when looking at machines of the period. The motor was effectively outdated and usurped in 1985 when the GSX-R750 was launched with its new air-/oil-cooled engine. Inevitably this power unit would find its way into other models of a less sporting nature, leading to the various GSX monikers confusingly being reused.