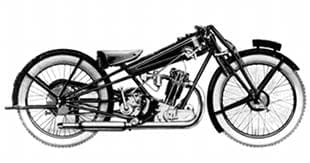

I’ve no idea how modern manufacturers teach their engineering students the rudiments of motorcycle frame design, but if it’s via computer software they are wasting time and money, and they’re also denying their pupils a whole heap of pleasure. Just let them loose on a vintage Cotton, and for evermore they’ll be convinced of the benefits of a rigid frame structure. And if that frame is allied to a lusty competition power unit – as it is in the latest gleaming addition to the Sammy Miller Museum – what more could they want?

For recent readers who only think of Cottons as Villiers-powered lightweights made by a resurrected company during the 1950s and early 1960s, it’s perhaps worth reprising the history of the original business, which involved several of the movers and shakers of pioneer days.

Francis Willoughby (Bill) Cotton was a law student in the early years of the last century and he keenly campaigned a Scott in local trials and hill climbs. The Yorkshire-made machine’s success was partly attributable to its revolutionary twin two-stroke engine, and partly to its light and stiff frame. Bill Cotton didn’t have the desire or facilities to make his own engine, but he could see that the frame’s stiffness came from its partial triangulation, and he decided to carry the principle to its logical extreme with a frame based on four straight tubes that ran between the steering head and the rear wheel spindle. In effect they formed triangles in both the horizontal and vertical planes, and only a fatigue fracture, or impact, could disrupt the alignment of the bike’s wheels.

Enjoy more classic motorcycle reading, Click here to subscribe to one of our leading magazines.

Patenting his design in July 1914 he claimed that it; ‘…provides a motor cycle with a strong light and rigid frame, combined with a low centre of gravity and improved riding position, weight distribution and fuel tank arrangement’. The last point was debatable, because the frame tubes inevitably compromised the tank’s design, but it didn’t take long to justify the other claims. Cotton was already acquainted with the Butterfield brothers who ran the established Levis company, and he got them to make a couple of prototypes. These proved to be so good that the Butterfields would happily have paid Bill Cotton for the manufacturing rights, but after a hiatus caused by WWI, he decided to set up in his own right.

Patenting his design in July 1914 he claimed that it; ‘…provides a motor cycle with a strong light and rigid frame, combined with a low centre of gravity and improved riding position, weight distribution and fuel tank arrangement’. The last point was debatable, because the frame tubes inevitably compromised the tank’s design, but it didn’t take long to justify the other claims. Cotton was already acquainted with the Butterfield brothers who ran the established Levis company, and he got them to make a couple of prototypes. These proved to be so good that the Butterfields would happily have paid Bill Cotton for the manufacturing rights, but after a hiatus caused by WWI, he decided to set up in his own right.

Acquiring premises in Gloucester in late 1918, Cotton initially made Villiers-engined lightweights, and followed the success of these machines with a larger one using a 350cc SV Blackburne engine. The Blackburne Company was run by Cecil and Alick Burney (hence the sometimes omitted ‘e’ on the end of the name), and was another well-established firm, having made proprietary engines since before WWI. Interestingly, complete Blackburne motorcycles were also available for a while, but these were probably actually assembled by OEC, and the South Coast firm soon took over that part of the business.

So, after 1921, the Burney brothers concentrated on what they did best, and simply made engines that were supplied to many of the contemporary manufacturers. The success of their side valve unit encouraged them to develop an overhead valve version, and Bill Cotton consequently added an OHV Cotton-Blackburne to his range. The combination of ample, controllable, power and superlative handling, created an instant hit, and the competition successes of Cotton-Blackburnes culminated in first, second and third places in the 1926 Lightweight TT.

Most motorcycle manufacturers’ frames were understandably intended to fit round specific engines, but the Cotton’s was designed purely to achieve stiffness. This had both advantages and drawbacks as the same frame could be used for a range of models, but specific mounts had to be devised for each new power unit. This was normally no problem, as the engine/gearbox assembly was effectively suspended from the headstock and saddle tube, with the gearbox braced to the rear wheel spindle. However, the new OHV Blackburne unit was simply too tall to sit beneath the frame, and while lesser men might have immediately changed the shape of the chassis, Bill Cotton simply tilted the engine forward until it fitted! Whether this encouraged other manufacturers to go down the ‘sloper’ route that became so fashionable in the following few years, we’ll never know, but the result certainly looked spot on, with the engine’s angle matching that of the front down tube.

Bill Cotton later compromised slightly on this aspect, and used a revised steering head casting that maintained strength, while splaying the front of the tubes out enough to accommodate the head of an upright cylinder. I suspect that this was done more for convenience’s sake than for styling reasons, because you only have to glance at the Miller Museum’s sloper to see that the tilt of its engine severely complicated access to the carburettor, and the new frame’s wider front end had the unwanted side effect of further increasing an already excessive turning circle.

Bill Cotton later compromised slightly on this aspect, and used a revised steering head casting that maintained strength, while splaying the front of the tubes out enough to accommodate the head of an upright cylinder. I suspect that this was done more for convenience’s sake than for styling reasons, because you only have to glance at the Miller Museum’s sloper to see that the tilt of its engine severely complicated access to the carburettor, and the new frame’s wider front end had the unwanted side effect of further increasing an already excessive turning circle.

The use of a saddle-style petrol tank – a change that occurred around the time this machine was made – has the same effect. And before experts rush to tell us what is and isn’t right for a late-Vintage Cotton, I must detail a curious set of circumstances that led Sammy Miller to be well aware that this particular motorcycle may well have originally featured the earlier type of tank that fitted between the frame tubes.

The machine came into his hands from the same local source as the racing Cotton that we featured in TCM October 2005, and for a long time Sammy knew nothing of its history. So when it came to the top of the list for restoration he did the obvious thing, and started looking at period sales literature to check on the original appearance of stock Cotton-Blackburnes.

“It seemed to be a 1929/30 Model 25 OHV Super de Luxe,” he tells me, “but one feature didn’t match up, and that was the design of the gear lever. The reference information showed a long lever pivoted near the back of the tank, while this bike’s lever was short and mounted at the front. I’d just about got the hacksaw in my hands ready to saw the pivot off and re-position it, when somebody passed me some old photographs (see one of the photos inset on the opening spread). Glancing through them, I was astonished to see a small-tank competition Cotton-Blackburne with a short, forward-mounted, gearlever, just like this one. And when I looked closer, there were other similarities between the bike in the photo and the Museum’s project. For instance, its front brake plate is set into the drum, which contrasts with the overlapping one fitted to standard Cottons of the period. Additionally, the Museum’s Cotton had been locally owned for years and one of the pictures had a nearby address scrawled on it, so all in all I was convinced that I’d got hold of the same bike, and decided to continue restoring it in the style shown in the photographs.

“A name that looks like ‘Les Harthorn’ is scribbled on the back of the photos,” Sam continues, “so he was presumably the owner or rider at the time, while the name above the local address is MK Field, and I guess he was a subsequent owner. Naturally, we’ve been round to 16 Merryfield Close, Bransgore, but the house has been demolished and built over, so the trail has gone cold, but if anybody knew either of these chaps or anything about their bikes, I’d be delighted to learn more.”

As it happens, the gear lever on the restored Cotton is inverted compared with the photos, but nobody expects competition bikes to remain in exactly the same trim for long. More importantly, another of the pictures shows the same – but obviously older – Les Harthorn with the racing Cotton-Blackburne we tested previously, so he was obviously devoted both to the marque and to competition, and it seems more than likely that Sammy’s hypothesis is correct.

The sort of detail Sammy would like cleared up is whether the Cotton was raced on or off-road. It’s certainly posed on a grass surface for the photographs, but that could simply have been for convenience’s sake. Whatever he did, Les Harthorn was obviously a serious competitor with smart leathers, boots and helmet – no second-hand roll-neck jerseys and jodhpurs for him!

The sort of detail Sammy would like cleared up is whether the Cotton was raced on or off-road. It’s certainly posed on a grass surface for the photographs, but that could simply have been for convenience’s sake. Whatever he did, Les Harthorn was obviously a serious competitor with smart leathers, boots and helmet – no second-hand roll-neck jerseys and jodhpurs for him!

At this time Cottons were available in practically any trim a customer wanted. For instance, most of the models in the OHV range could alternatively be supplied with JAP engines (strangely, one model – the 25SA – was only available with a Sturmey Archer engine); and that was without extra charge, which just goes to show how easily the frame could accommodate different power units! What might be significant for this particular machine is that Cottons could be supplied in track trim.

A section of the sales leaflet explains all about it: ‘The Cotton is probably the only standard design capable of withstanding these severe strains without strutting or mutilating. Any of the OHV models can be had to special order in Dirt or Grass Track or Sprint form without extra charge. Optional specification: Sprint streamlined tank – one or both brakes – kneeirons – special gear ratios, etc’. No extra charge, eh! Well that confirms what I wrote about the frame’s adaptability, and the fact that the same frame could feature in at least four different models shows how difficult it is to identify a particular machine’s function, and how futile it is to worry about its precise specification.

So let’s get back to what we do know about – the bike in its present state of trim. The fact that we testers have to consider the needs of the cameraman while riding test machines means that we have limited time and opportunity to actually make our assessment. This doesn’t matter too much, since stopping, starting and manoeuvring can usually tell you more about a bike than a day of straightforward riding. Just occasionally, though, we ride a bike that begs for a longer acquaintance, and have to remain frustrated.

Sometimes that’s because the restoration is too new to be put to a more severe test, and sometimes it’s because of mechanical problems. Well the Cotton-Blackburne had barely been used prior to my ride, and yes, it did have a bit of clutch slip. But the real problem was that, with no number plates or silencer it would simply have attracted unwanted attention on the open road. Consequently I had to give it a limited gallop on private land, and it didn’t really get into its stride.

What a shame! The Blackburne motor was one of the best of its era, and arguably somewhat more sophisticated than the rival JAP engines. In fact, apart from its exposed pushrods the motor matches practically anything available a quarter of a century later. As far as I can tell above the bellow of the open exhaust it’s reasonably quiet mechanically, it’s certainly fairly smooth, and it GOES.

Cotton quoted a top speed of 85mph for the Model 25 and that’s better than was achieved by many half-litre singles in the 1950s. The motor certainly feels pokey enough for that sort of speed, so for once I’ve no reason to disbelieve a manufacturer’s publicity material.

Even better, the motor doesn’t have much motorcycle to shift. Cotton quoted a weight that wouldn’t have seemed excessive on a post-war 250cc job, so the typical pre-war torque guarantees sturdy acceleration and effortless speed.

And best of all – at the risk of labouring my theme – is that the frame allows all of the performance to be used. There are many vintage motorcycles that you wouldn’t let a modern biker loose on, in case the experience put him (or her) off old bikes for life, but the Cotton is one of those machines that makes any rider feel immediately at home and in full control.

Even road bumps don’t disrupt the road holding, but naturally they quickly remind you that armchair comfort is a non-available option on an old rigid bike. What’s more, there was never any chance of adding rear suspension to traditional Cottons, because their handling – and lightness – depended on not having excessive frame members and extra joints.

Even road bumps don’t disrupt the road holding, but naturally they quickly remind you that armchair comfort is a non-available option on an old rigid bike. What’s more, there was never any chance of adding rear suspension to traditional Cottons, because their handling – and lightness – depended on not having excessive frame members and extra joints.

It’s a small price to pay for this kind of motorcycling pleasure. Put a bobby-dodging silencer and number plates on this machine, and I’d be first in the queue to give it a blast up Sunrising Hill on the Banbury Run. As it is, I would be very surprised if Sammy Miller can be prised out of the saddle on demonstration days.

Competition Cottons

In the 20s, Cotton was an active firm in the competition sphere, fielding a strong team at the TT most seasons. Among the riders who found success on a Cotton was a youngster by the name of Stanley Woods, winner of the 1923 Junior TT on a Blackburn-engined example.

1960s

1960s

When Villiers made the Starmaker engine available for competition use, Cotton was one of a number of makers who decided to make a road racer around the power unit. The Telstar was the result and it was ridden by such illustrious names as Derek Minter.

In the late 70s, Cotton made a racing comeback with the single cylinder Rotax-powered LCRS, aimed at the clubman. It was followed by more complex tandem twin and V-twin engined racers. LC originally was an acronym for ‘Liquid Cooled’ but it became ‘Low Cost’.