Valve bounce happens at high revs when the valve springs are unable to respond quickly enough to close the valve back on their seats. The desmodromic idea was to replace troublesome springs with a mechanical closing system much like that used to open them. Eliminate the springs and you eliminate the bounce and get a higher-revving engine — in theory.

This had been known since the early days of the internal combustion engine but for many years no designer managed to successfully harness it.

Interest in desmodromic valve operation had waned until in 1954 the giant Mercedes Benz concern decided that something better than spring return was required for its new W196 2½ litre grand prix engine. The German company therefore evolved a desmodromic layout, the success of which was evident if one consults the car’s 1954 racing record. The unsupercharged, straight-eight cylinder engine was reputed to develop over 260bhp (or 104bhp per litre). With an individual cylinder capacity of 312cc it is easier to see that this design was still of interest to the motorcycle world.

Two cams per valve were used by Mercedes (as on the Delage engine), and each cam had its own rocker. The rockers were pivoted side-by-side on a common shaft and had a scissors disposition. The opening rocker bore on a shoulder part way down the valve stem, and the closing rocker on a collar near the end of the stem.

Two cams per valve were used by Mercedes (as on the Delage engine), and each cam had its own rocker. The rockers were pivoted side-by-side on a common shaft and had a scissors disposition. The opening rocker bore on a shoulder part way down the valve stem, and the closing rocker on a collar near the end of the stem.

Originally the design embodied final closure of the valves by springs, but the springs were dispensed with after tests had revealed them to be unnecessary. All that was required was an ultra small clearance and pressure inside the cylinder did the rest. Thus simply was one of the original problems overcome!

Whereas the cam track principal described earlier is easy to understand, the double cam arrangement requires a brief explanation.

The opening cam is of conventional form, while the closing cam is, in effect, an inversion of the opener: it begins to drop from its base circle when the opening cam lifts from its base circle; the peak on the opener coincides with the lowest point on the closer, and the closer lifts from its lowest point as the opener comes off its open dwell on to the return flank.

Motorcycle sphere

Besides Mercedes the motorcycle sphere had also seen several designers show a distinct interest in desmodromic valve operation around that time, most notably Joe Craig, (race supremo at Norton in the early 1950s) and more significantly in the Desmo story, Ing. Fabio Taglioni. Ing. stands for Ingegnere, the Italian for engineer. In a country with as proud an engineering heritage as Italy, its a title which commands respect and its men like Taglioni who made it so. And, unlike Craig, Taglioni was able to launch his ideas from the drawing board into metal.

In the late 1940s, whilst studying as a young man at Bologna University, Taglioni had first put pen to paper to conceive his initial motorcycle engine designs which included desmodromics and a 90 degree, L shaped V-four 250!

Taglioni worked for F B Mondial during the early 1950s upon graduating from University. At that time Mondial were one of the most successful marques in Grand Prix racing. And as they specialized in the lightweight classics this meant specializing in the problems associated with high engine revolutions. It was during this period that Taglioni first tried to exploit the potential for desmodromics. However, it was not until he joined Ducati in early 1955, that he was able to develop many of his ideas through to fruition — including positive valve closure.

It was this year that saw Ducati’s first serious attempts at road racing; up to Taglioni’s arrival, the works had converted standard machines to take part in local events, which, for the most part, meant either trials or long distance road races.

It was this year that saw Ducati’s first serious attempts at road racing; up to Taglioni’s arrival, the works had converted standard machines to take part in local events, which, for the most part, meant either trials or long distance road races.

Taglioni’s first design for his new employers was a 98cc single overhead cam model, the 100 Gran Sport. This sports roadster-cum-racer was soon the most popular in its class for the long distances road races of the day and helped to launch the careers of such acclaimed riders as Spaggiari, Pagani, Francesco Villa, Gandossi Fame and Mandolini.

But the Gran Sport project had not been conceived purely as an over-the-counter racer. It was to be the spark which inspired not only the company’s range of single cylinder roadsters for the next two decades, but also the base for a full scale venture into Grand Prix racing. For the early racing, Taglioni first produced a dohc version of the Gran Sport, enlarged to 124cc (55.25 x 52mm) Except for a complete new cylinder head assembly, a truly massive casting which housed the complex valve gear, and five speed gearbox, it was virtually identical to the original design. But although this proved reliable it was not fast enough to challenge the class leaders, MV Agusta.

Enter Taglioni’s first desmodromic design to turn wheels. This used the same 55.25 x 52mm bore and stroke, ran on a compression ratio of 10.5:1 and used a titanium con-rod that was double webbed at top and bottom to withstand the stresses of sustained high evolutions.

Increasing vulnerability

The chief problem Taglioni faced convinced him of the need to use desmodromics – the increasing vulnerability of orthodox valve gear to overrevving. Quite simply, higher maximum revs inevitably meant an extension of valve timings and wider overlap periods around tdc. In addition larger valves meant less clearance between them during overlap. Despite the use of dohc to reduce reciprocating weight, a brief bout of over-revving, however caused, spelled disaster, with the tiny clearance found on a high revving ultra lightweight class engine proving insufficient and the inevitable result of the valves kissing. Meanwhile increasingly high compression ratios meant less valve-to-piston tolerance, and a rising piston could then overtake a floating exhaust valve. Either way the engine was damaged and the race lost.

Taglioni’s solution was to dispense with valve springs and use the cams to close the valves, assisted by additional rockers. And unlike the majority of earlier designers Taglioni had not been tempted to use some form of spring in the system. The only disadvantage (which he openly admitted) was in the event of a piece of grit, however small, getting trapped under the valve seat. But the risk was one Taglioni preferred to take in his quest for maximum performance.

In its conversion from dohc to desmo the 1956 Ducati 125 racer gained 3bhp (19bhp at 12,500rpm against 16bhp at 12,000rpm).

Prior to the desmo’s debut came a long period of exhaustive factory tests. Taglioni wanted his baby right first time. Experimental engines had been run on the test bench for up to 100 hours at full throttle! Meanwhile, on the track testers had hurtled around sometimes exceeding 15000rpm with no ill effects – unheard of at the time.

With a profound confidence in the new machines speed and ability to keep going, the factory readied the racer for its first competitive outing. They picked the 1956 Swedish GP at Hedemora, which although a non championship event at the time, still nonetheless had attracted a top class entry.

Something special

However, as soon as Antoni started to warm up his engine, onlookers knew that here was something special. This newcomer sounded deep, mellow and powerful. It was a suspicion that was confirmed in the first practice session, when the engine note rose to an intense wail like an angry wasp as the machine swept around the circuit. Once the race started, Antoni showed just how superb the desmo single really was, setting the fastest lap, lapping every other rider at least once and finally finishing the race in record time.

How many other factories have had such a Grand Prix debut, or such a foundation on which to build a legend…

How many other factories have had such a Grand Prix debut, or such a foundation on which to build a legend…

But along the way there were to be many pitfalls and heartaches before the word desmodromic was to become an accepted part of the everyday motorcycling vocabulary.

Following his historical Swedish GP victory, Antoni had returned home to Italy with the winning desmo prototype. But unknown to him and Ducati disaster was just around the corner. In his very hour of glory, with the prestigious Italian round of the world championship at Monza, Antoni took his 125 desmo out for a test session at the circuit. Tragically, he crashed on the Lesmo Curve and died from his injuries.

Antoni’s death effectively stopped Taglioni and Ducati in their tracks and a whole year and more was to pass before Ducati were once again ready to mount a challenge for Grand Prix honours.

This came at the first round of the 1958 125cc World Championship – the Isle of Man TT. For this Ducati fielded four riders, Romolo Ferri, Luigi Taveri, Dave Chadwick and Sammy Miller – all competent competitors, but not in the class of the two MV pilots, Carlo Ubbiali and Tarquinio Provini. Even so desmodromic Ducatis took second, third and fourth places in the race.

Even better was to come. The next round, the Belgian GP, was held over the super fast Spa Francorchamps circuit. Here speed, rather than riding ability was the prime requirement and the Bologna desmos clearly demonstrated their potential by taking first, second, fourth and sixth places with world champion Ubbiali relegated to fifth spot!

And it is generally accepted that if Ducati’s leading rider Alberto Gandossi (who had not ridden in the Isle of Man) had not fallen in Ulster, he, rather than Ubbiali, would have been champion at the season’s end. The final found at Monza had seen the mighty MVs annihilated, with Ducati taking the first five places. A brand new prototype twin cylinder model finished third.

Unfortunately just when Taglioni’s brain child seemed likely to totally dominate the ultra lightweight racing category, a change in factory policy meant only limited participation the following season. Even so an 18year-old youngster named Mike Hailwood had his first GP victory (at the Ulster GP) on a desmo single that year.

Stan Hailwood, Mike’s father, had been so impressed with the desmo’s performance during 1958 that he bought Mike a couple of works 125 desmo singles, and even commissioned 250 and 350 twin cylinder versions. These latter two designs would no doubt have had a better chance of repeating the single desmos success had they been developed by the factory, rather than being purchased, largely untested, by the Hail-wood equipe.

During the period 1958 to 1961 many others tried unsuccessfully, to emulate Taglioni’s success. Firstly, Mondial would most likely have raced a desmodromic 250 in 1958 had they continued racing. Benelli experimented but gave up. A desmodromic version of the Manx Norton was built, but this was not proceeded with. Even private concerns, such as Velocette specialists BMG of llford, Essex, converted a 500 Venom to desmodromic valve operation, but none were anywhere as successful as Ducati.

During the period 1958 to 1961 many others tried unsuccessfully, to emulate Taglioni’s success. Firstly, Mondial would most likely have raced a desmodromic 250 in 1958 had they continued racing. Benelli experimented but gave up. A desmodromic version of the Manx Norton was built, but this was not proceeded with. Even private concerns, such as Velocette specialists BMG of llford, Essex, converted a 500 Venom to desmodromic valve operation, but none were anywhere as successful as Ducati.

But probably Taglioni’s crowning glory came in 1968 with the introduction of the first mass production motorcycle (or for that matter vehicle), with desmodromic valve operation.

For a man who believed that the simple things were usually the best, the newcomers were eactly the same as their Mark 3 ohc brothers from the cylinder barrel downwards. The mechanical operation for valve opening and closing was similar (although with only one camshaft) to the type that Taglioni had devised for his earlier desmo racing machines. The main difference was that in the roadsters the valve closing was assisted by springs, unlike the racers.

However, the springs used were very much lighter than the ones on non-desmo models (in fact, they were from the 125/160 roadsters). And as proof of Ing. Taglioni’s simply-is-best-approach, many of the cylinder head’s less critical components were borrowed from existing production models giving both Taglioni’s production staff and potential owners a far easier time when spares were needed.

Compared with the valve spring engines valve seat pressure of 80lb/square inch, the desmo was 81b/square inch making kickstarting easier and giving much less seat wear — both important advantages for road-going units.

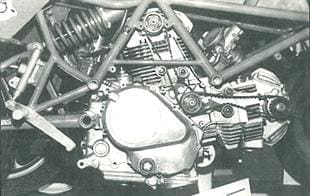

The only real difference between the standard valve spring Mark 3 and Desmo engine was, that the latter had four rockers (in place of two on the Mark 3) and a four lobe camshaft, in place of two. Even the valve head diameter and materials were identical but the method of valve stem collect retention was different!

The commercial success of the single cylinder desmo roadsters meant that when the factory introduced its V-twin range in the early 1970’s it was not long before Desmo versions of these too began to appear.

By 1980 all Ducati production motorcycles had desmodromic valve operation and this is the picture today. This sales success is surely lasting proof of an idea which had its roots firmly in the veteran and vintage days of motorcycling, but even today is viewed by many as being amongst the very vanguard of two wheel progress — a rare achievement indeed.