With production constraints dictating design, manufacturers must compromise and offer the market something not quite ideal… there are

those who can improve things later though.

Words: Tim Britton Media Ltd Pics: Mortons Archive

Let’s go back in time nearly 70 years to the late 1950s. Imagine you’re in the boardroom of BSA, the biggest motorcycle manufacturer in the world, a manufacturer who can proudly boast one in four motorcycles sold in the world are made in its factory… The press of the day carries reports of the company’s sporting successes in trials, scrambles, the ISDT and even those sports where motorcycles have funny smooth tyres rather than proper knobblies. The Docker family has gone and the company is under the guidance of JY Sangster. All appears well in the world until the competition manager announces there is a problem. Silence ensues, then the comp manager explains the flagship Gold Star model – which had dominated racing and off road sport for years – was on its limit. Voices chirp up: “But we’re still winning championships, races, trials and we can sell every motorcycle we make…” All true, confirms the manager, but adds: “The wins are due to the calibre of rider we can afford and they’re finding it harder and harder to succeed.”

The revelations get worse: lightweight machines with less power but a better power-to-weight ratio are besting the Goldie and the word on the company grapevine is the B31/33 range from which the Goldie is derived will soon end. Something needs to be done… and done quickly.

The competition manager offers a ray of hope: “My deputy Brian Martin has had a look at the new C15 roadster and made a trials bike out of it. It went rather well too and he was within a whisker of winning the premier award in his first trial on it when he stopped to help a fellow competitor and accrued one extra penalty point.” The manager carries on by saying: “The comp shop feels there is scrambles potential in the little 250 too and of course the Government is going to impose a 250cc limit for learners from 1961 so perhaps us championing the C15 in trials and scrambles will encourage fledgling motorcyclists to look at the roadster model…” He lets the thought hang in the air for the board members to digest.

An interesting story. Did it happen this way? I doubt it, but the undeniable facts are the Goldie was coming to the end of its life, as was the B31/33 range; lightweight machines of 200/250cc were dominating trials and starting to challenge the 500s in scrambling. BSA had introduced the C15 as a mild-mannered ride-to-work machine with no sporting pretensions at all yet the factory team had taken the 250 and was winning trials on it and no lesser lights than Jeff Smith and Arthur Lampkin were taking on the scrambles world. In events where there were no capacity restrictions they were showing the 500s the way home.

The 1959 C15 was certainly filled with potential, and history will record that the machine formed the basis for Jeff Smith’s world championship-winning 420 in 1964 though the development in between the two extremes was considerable. To backtrack slightly though, BSA was sufficiently impressed by the C15’s potential in trials and scrambles to instigate a production run of both models. Problem was, as a massive concern the company was very good at large production runs but not so good at smaller ones and, like it or not, the annual market for 250cc trials and scrambles machines wasn’t huge. BSA tackled this in its own style by doing a large, profitable production run of each machine in 1959 and stockpiling them so a batch could be released each season…

Closely related to the roadster range, the C15T and C15S had the same brazed and lugged frame, same forks and same wheel hubs. The trials model got different fork yokes and each model had different engine internals, but these were minor differences and they both resembled the roadster which was an important consideration for the manufacturer.

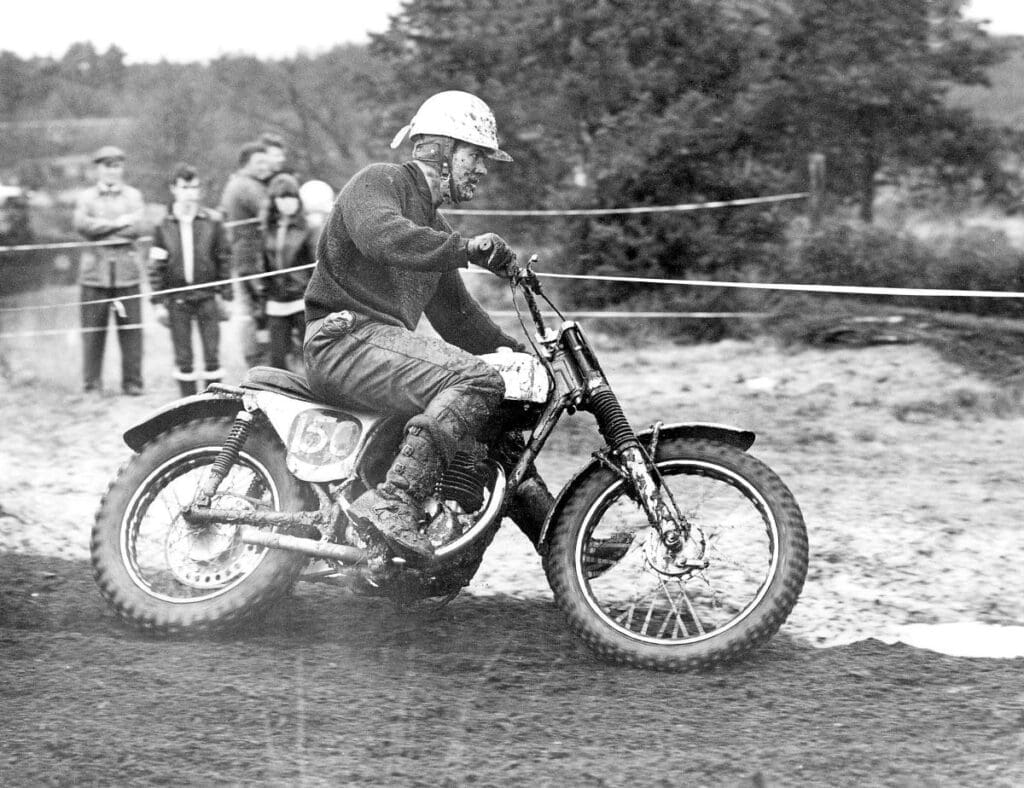

bit… MX equipment at practice sessions was more basic in 1966.

The production bikes carried on this way for several seasons while the comp shop produced ever more developed machines for Jeff Smith to race. This isn’t to say improvements weren’t passed on, they were.

The C15 got steel flywheels across the range instead of cast iron and there was the improved oil pump too… but these were minimal mods. In answer to the question: “Will there be a Smith replica?” the factory denied it was anything more than a testbed for ideas and yes, it would be nice to win a championship but no, we don’t plan on producing a replica. The first major 250cc improvement came in 1963 when an all-welded and lighter frame was introduced for the C15T and C15S.

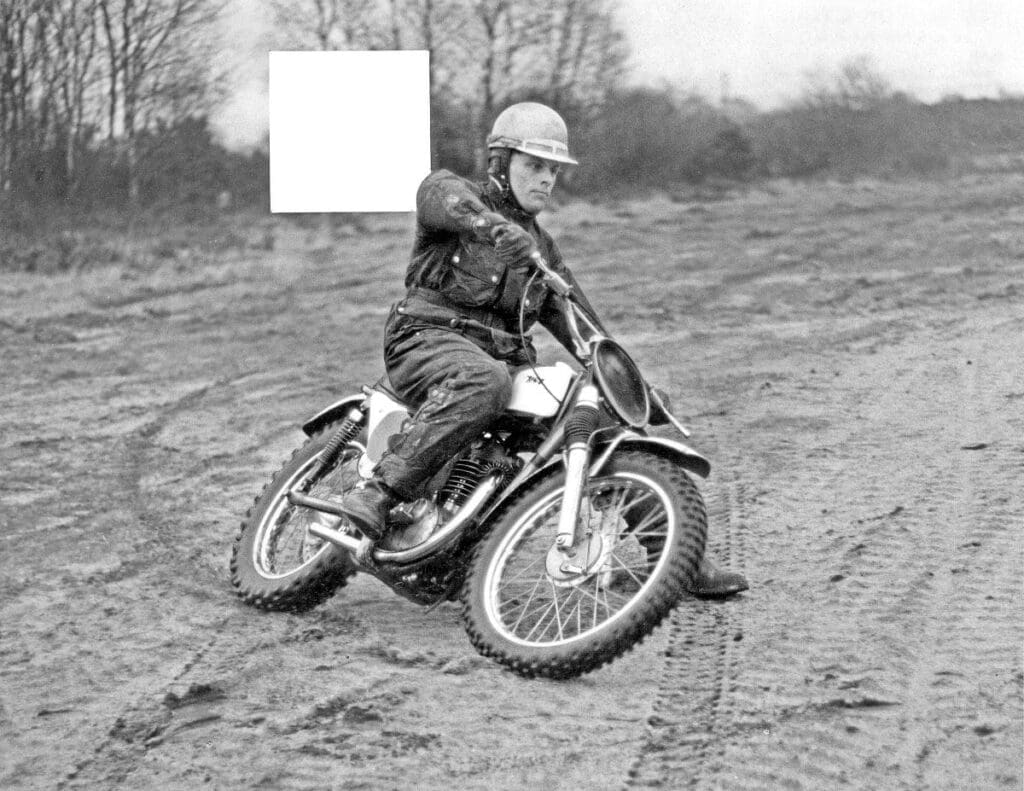

Though the factory was happy with the standard model and even happier to let the comp shop produce special bikes for Jeff Smith this didn’t mean other people hadn’t kept an eye on the 250 model. This brings us nicely to the pics in this feature which are Eric Cheney’s take on what a C15S should be like.

Because BSA was focused on Jeff Smith’s campaign in the 500cc MX championship and, by 1966, there was a production Victor of 441cc, the poor old 250 model once again fell by the wayside, at least as far as the factory was concerned. In part this was because the majority of the 250s being raced were two-strokes and their development had gone extremely well to the point where BSA’s production 250 was too heavy and too slow. Ironically the factory’s work with Smith’s bike showed what could be done to make a four-stroke really work, a fact not lost on the outside world. Now in this rarefied atmosphere of top-level MX where factories contest the championships there are those private individuals who have a closer working relationship with the works teams than most other people. Such an individual was Eric Cheney, himself a former top motocrosser until health problems curtailed his racing. Eric was always noted for the excellent preparation of his machines and turned his attention fully to building motorcycles which went so well the factories kept an eye on them.

The feeling from the Cheney HQ was his rider Jerry Scott could be doing with a 250 BSA to go alongside the 500 Gold Star he was racing for Cheney. Eric wondered if the same sort of work he was doing for the ostensibly obsolete 500 would work with a 250. The resulting machine was featured in MotorCycle’s pages in early 1966 when Peter Fraser was invited along to a test day.

Of the many attributes Eric Cheney had, fantasist wasn’t among them. If he didn’t think he could make the C15S work much better, then he wouldn’t have spent a lot of time patiently working on the power unit and using his own proven ideas in the project. After all’s said and done, the lad was in business to make money and his earnings depended on being seen to be winning.

The tale of the 250 which Fraser was presented with one snowy February day began the previous year and was with the blessing of the BSA factory too. It isn’t clear in the feature if this meant there was the occasional special part available, but it was suggested none other than BSA’s reigning world champion MXer could be using the Cheney 250 in the BBC Grandstand winter series.

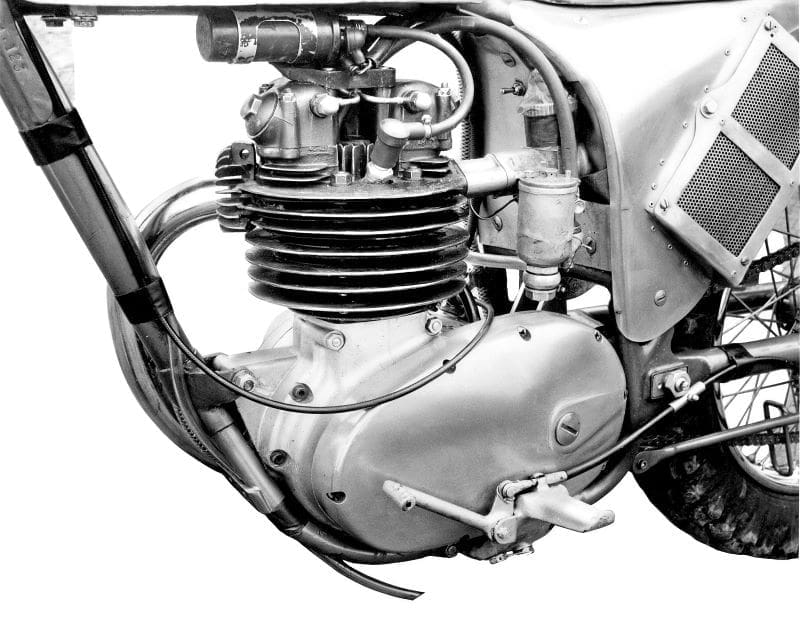

Before Peter got a test ride of the bike the lad had popped along to Cheney HQ and had a look at the bike in its early stages and revealed a few, not all, of the secrets. Biggest change was to the oiling system and instead of a timing side bush there was a large roller bearing which meant the oil had to reach the big end by a different route from standard. So instead of feeding oil in through a hole in a bush it was fed to the big end through a drilled mainshaft which ensured plenty of lube got to where it should. Eric had also smoothed and polished things like the con rod and flywheels to minimise oil drag as the liquid worked its way round the engine. This word ‘drag’ is quite an important one in the engine building world and unless components supposed to spin can actually spin easily then this has an effect on performance. BSA used, as did many other British factories, bushes for shafts to run in; nothing wrong with them if you want an engine to last for several thousand miles and have a gentle running-in period. A running-in period is a luxury most MX teams don’t have so Cheney replaced the bushes with needle roller bearings which may not last as long but spin freely from the get-go.

When Fraser viewed the engine the most obvious difference to a standard C15S was the barrel. Instead of cast iron this barrel was alloy and further modified with each alternate fin having more alloy welded on to increase the cooling area available to the engine. The head too had some extra alloy on it and an extra spark plug in it. This was an experiment to ensure the fuel mixture was fully burnt during ignition and it was hoped to increase the performance so a basic four-stroke could match two-stroke performance. Also in the cylinder head Cheney had used very high-quality Nimonic (yes, I looked it up too, an incredible metal) alloy valves as used in the Goldie to ensure they would last the distance. All these changes and additional cooling meant the engine could happily cope with an 11:1 compression ratio with the fuel of the day more than adequate for such figures.

Other changes inside the engine revolved around the lightening of the valve gear and the cam wheel; oh, and the cam profile was to Cheney’s spec rather than BSA’s. Naturally one of the effects of more revs tends to be increased crank case pressure, something often overlooked in engine building, possibly because claiming: “Oh yes, I got the crank case pressure down a lot…” doesn’t sound as glamorous as saying how you upped the compression ratio or tweaked the cam timing. Doesn’t mean it isn’t important though. Cheney modified the crank case behind the cylinder to accept a B31 breather which does the job nicely.

at the old distributor mount.

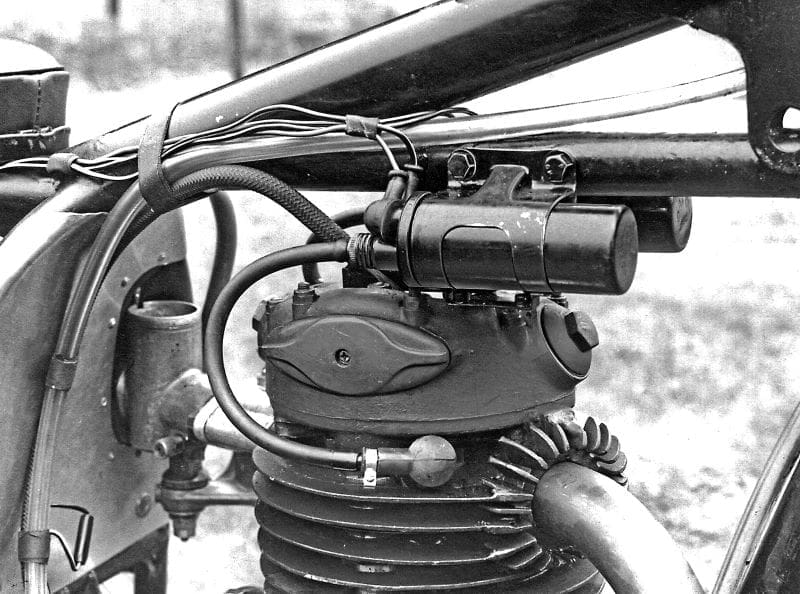

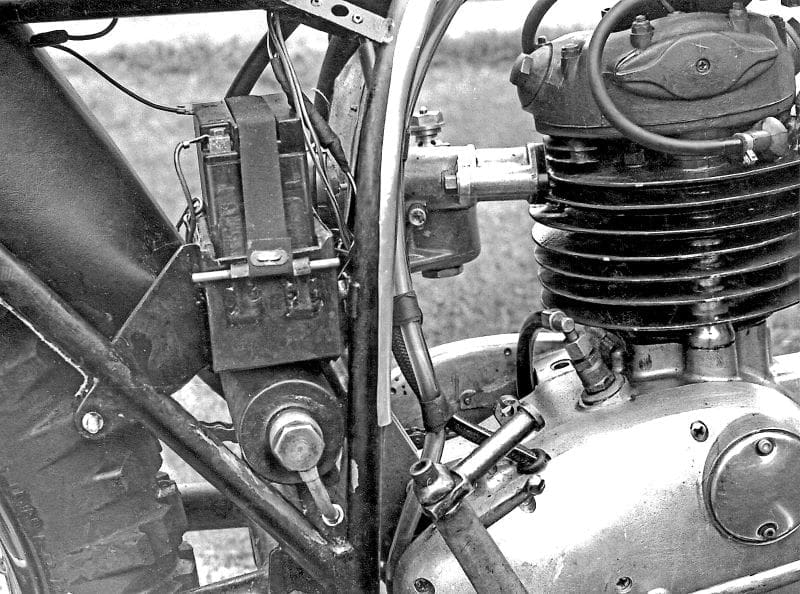

An energy transfer ignition system would have been standard on the BSA – a Lucas item and either the spawn of the devil or a great system depending on who you speak to. Cheney did away with it completely and used a tiny battery to power the coils which meant he could shorten the engine’s mainshaft and slim down the primary drive as well as the primary case. This does a bit of good in the weight-saving department too.

Housing the engine in a modified Victor frame which has a cylindrical oil tank in place of the flat header tank of the standard frame means it is in the lightest scrambles chassis available and interestingly Cheney moved the footrests forward of their standard position. Fraser left the Cheney HQ with the offer to come back when the bike was ready for action and it was one snowy February day in 1966 when the Barbour-suited journalist tackled the frozen terrain on the bike. Before setting out on the practice track he was updated on the rest of the bike’s details and learned the wheels were built on to Husqvarna hubs – though modified to take bigger spindles – with the front wheel retaining the 20in rim BSA favoured. This was mounted in forks of his own creation using bits from several sources with alloy yokes made from scratch. There had also been some more work in the frame area with the subframe and swinging arm now being of Cheney’s own ideas but mated to the front part of the Victor one.

In his inspection of the model Fraser noted there was just one spark plug – there’d been two on the original version he’d described in MotorCycle. Eric explained under testing it was found the power gain from a twin-plug system over a single plug was negligible so, when balancing the tiny power-gain against the extra weight and added complication of a twin-plug set-up, he reverted to a single plug. The power source was still by a battery though and of the type used in de Havilland’s ballistic missile! Feeding of the mixture into the engine was now by an Amal GP5 race carb mounted on an extended inlet tract which mirrored BSA’s findings on power gain from extending the inlet which breathed through a Vokes air filter as no wants muck being sucked into the carb.

Before setting off on his test ride Peter explained he wasn’t expecting trials type of bottom end power from an engine expected to tackle the might of two-strokes in MX GPs; but he was pleased to find things started happening as he got towards half throttle and instead of a violent blast the power was controllable right the way through the rest of the range.

Though the clutch was extremely light in its action and neither slipped nor dragged at any point, Fraser found he didn’t use it much during his ride as easing the throttle and nudging the gear lever had cogs slipping sweetly into place. There was no mention from the Cheney camp as to gear ratios but it is likely they were the original ones the C15S was supplied with.

A typical scrambles course has a multitude of gnarly terrain to catch out the unwary rider or the bike with questionable suspension, yet MotorCycle’s man had complete confidence in the handling of this smart 250. Gullies, ripples, cross-camber ledges were all dealt with safely and Peter admitted the bike was flattering his ability and while a handy off-road rider, by his own admission he wasn’t in the league of Jerry Scott who campaigned Cheney’s Gold Star.

Naturally as expected of the bike the build quality and finish were superb and the polished alloy was set off by a stylish blue on the tank. All in all, the result of Eric Cheney’s work was deemed successful and the throaty rumble of a four-stroke would be a welcome sound among the ring-a-ding twostrokes at a scramble or MX. The coming season was anticipated with interest…